4 answers to the RBA’s toughest questions

Yarra Capital Management

After six months of sitting on the sidelines, the RBA has finally eased rates. It’s left many questioning their timing. So, we decided to explore what shifted in their thinking through a series of pertinent questions & answers.

Q1: What was the RBA waiting for?

For the past six months, this has been an extremely difficult question to answer given how subdued the RBA has been at using unconventional policy compared to offshore. No matter what angle we took when looking for answers, we kept landing on the same two reasons why they should be doing more:

- Typically in a recession central banks cut rates 400 to 600 basis points (currently the RBA has cut 100 – 200 bps).

- Central bank research from offshore confirms that quantitative easing (QE) works.

If QE works and the RBA hasn’t even eased half of the 400 basis points required, why has the RBA been so reluctant to cut?

Fortunately, the RBA provided the answer:

“When the pandemic was at its worst and there were severe restrictions on activity we judged that there was little to be gained from further monetary easing. The solutions to the problems the country faced lay elsewhere. As the economy opens up, though, it is reasonable to expect that further monetary easing would get more traction than was the case earlier.”

— “The Recovery From a Very Uneven Recession”, Phillip Lowe Speech, 15/10/20

As the economy opens up, the RBA believes that easier rates will have more traction. This makes a lot of sense intuitively, since businesses probably didn’t need a lot of credit when they were operating at a reduced capacity with significant government support.

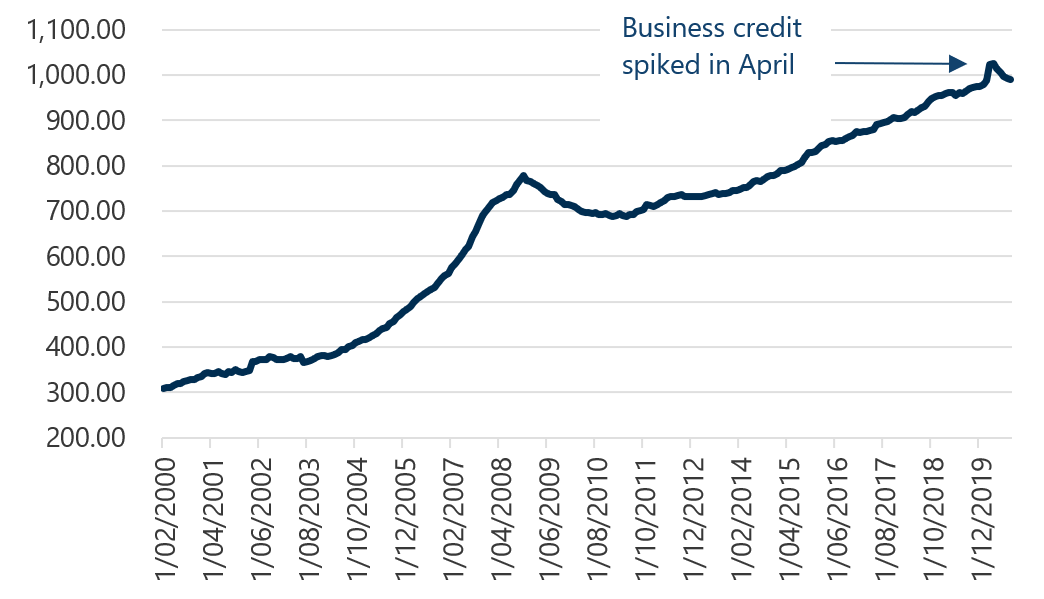

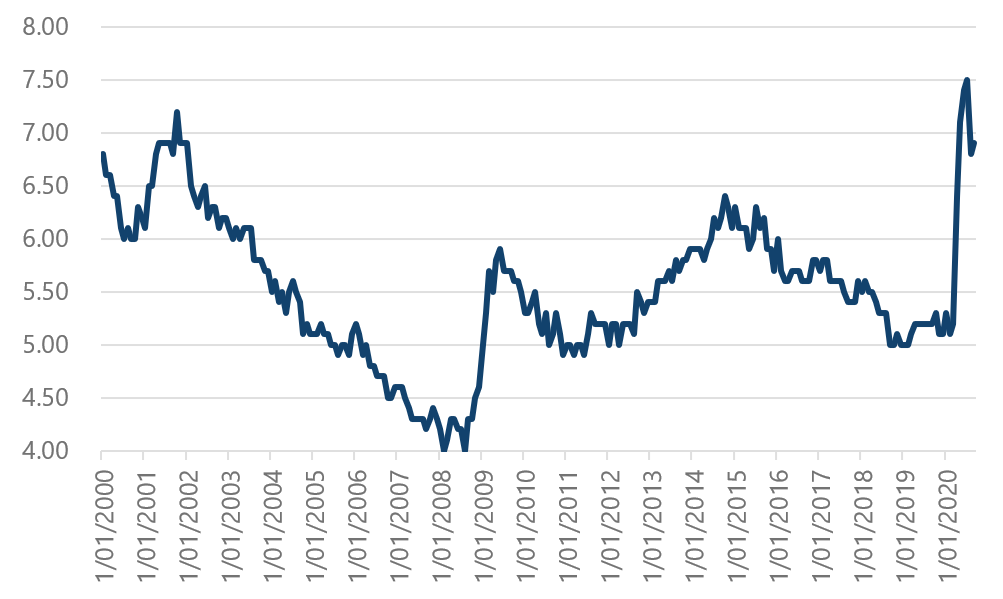

You can see this in Chart 1. Business credit spiked in March/April, but has since reduced despite the poor economic environment. So, even with more easing over the past six months, it is doubtful that it would have encouraged more borrowing during the period.

Chart 1 – Australian total business credit

Source: Bloomberg

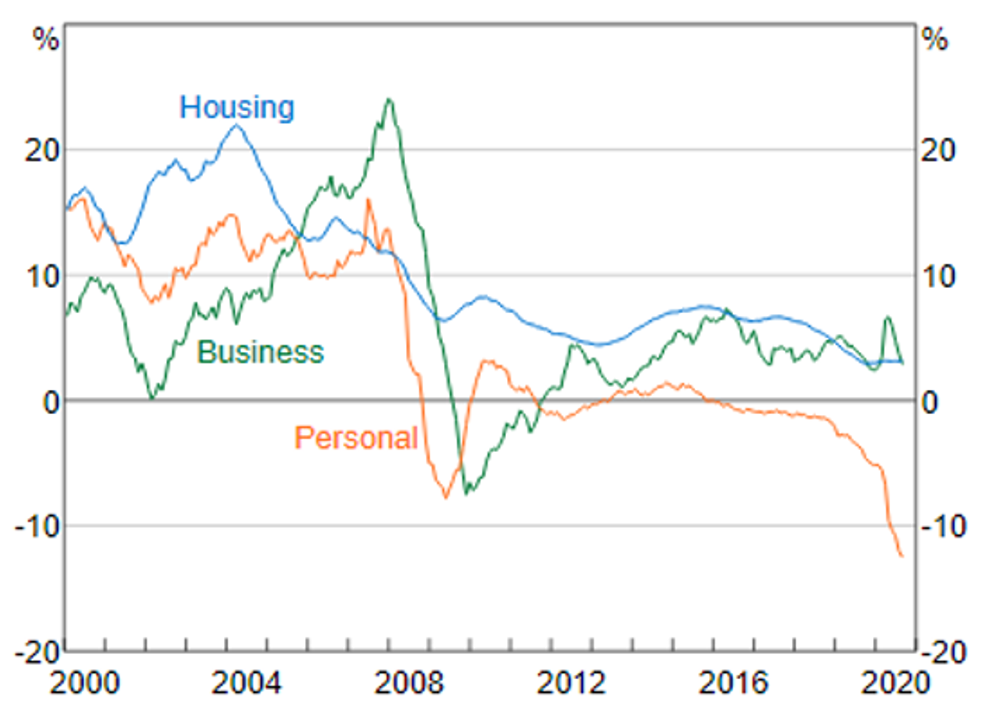

This is even more obvious from a personal credit perspective, with the RBA showing credit growth in the personal sector worse than the GFC. Any effect from further rate cuts over the past six months would have been muted for personal borrowers.

Chart 2 – Credit growth by sector (year-end)

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

This argument, however, does seem to have some inconsistency. For example, does it make sense to not cut rates over the past three months simply because they might have more effect now? Wouldn’t the low rates still be around to provide stimulus as the economy reopens?

Regardless of the arguments, the key take away is that the RBA still believes monetary policy and quantitative easing work. They were just waiting for the opportune time to deploy it.

Q2: Why wait until the outlook was improving?

The second question worth exploring is: why the RBA cut rates now, given economic forecasts are looking better. Unemployment likely won’t spike as high as originally expected, Victoria has just reopened, retail sales have been relatively strong and the worst of it (hopefully) seems to be behind us.

However, the reason to add more support in light of this is due to how “uneven” the recovery of the economy will be. Some sectors will likely perform well, while others remain in an extremely tough situation. To see how important this is to the RBA, we only need to look to the title of Governor Lowes’ latest speech: “The Recovery from a Very Uneven Recession”

Here is what Lowe said at the beginning of that speech:

“I would now like to turn to a second factor that will shape the recovery – that is the shadow cast by the very uneven nature of the recession that we have been living through. All recessions are uneven, but this one has been especially so. The government has wisely sought to even things out, but inevitably we are left with outcomes that are very uneven across the country.”

—“The Recovery From a Very Uneven Recession”, Phillip Lowe Speech, 15/10/20

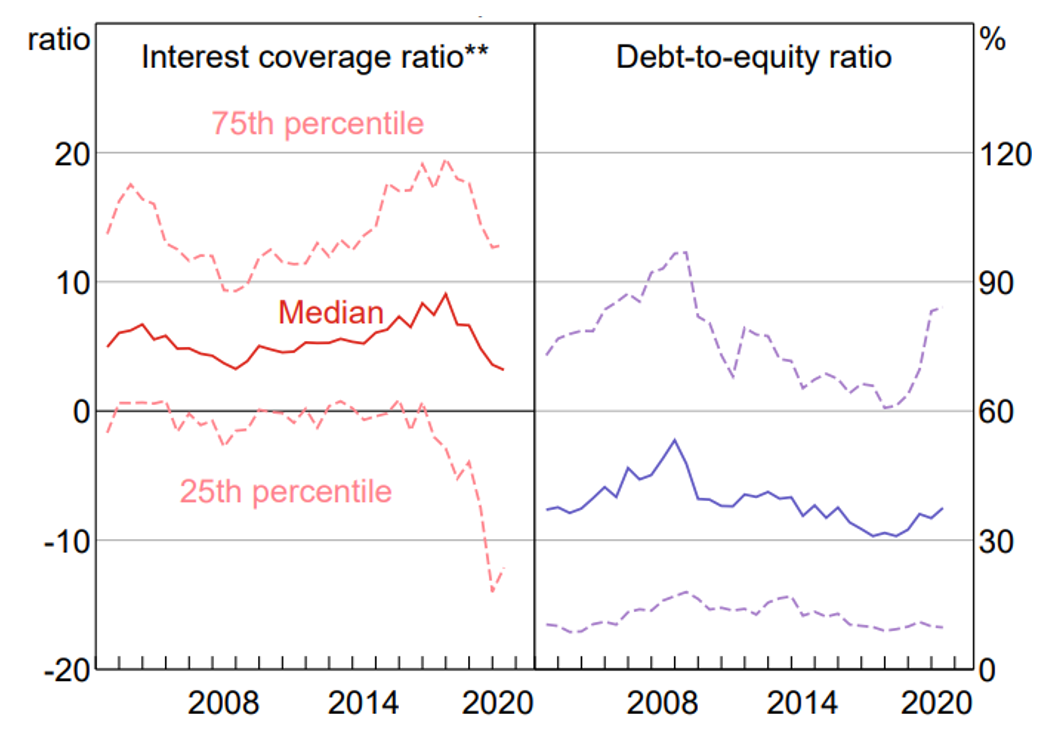

One obvious place to look for evidence of an uneven recession is the effect on businesses in Australia. Some businesses have come through the COVID-19 crisis unscathed, while others remain in a perilous position. Chart 3 from the RBA shows the interest coverage ratio of corporates across Australia.

Chart 3 – Corporate debt servicing indicators* (for companies with debt)

Source: Financial Stability Review October 2020, Reserve Bank of Australia. *Excludes all companies in the resource and financial sectors. **Interest coverage measured as the ration of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) to gross interest payments

The left hand panel of this chart shows that for the bottom 25th percentile of Australian corporates with debt, the interest cover ratio is not just negative, but massively so. What does this ratio of -12x mean? That the interest payable for these companies is 12x larger than the earnings that they are receiving.

Here is how the RBA describes the position of these firms.

“At least 10–15 per cent of small businesses in the hardest-hit industries still do not have enough cash on hand to meet their monthly expenses. These businesses are in a tenuous position and are particularly vulnerable to a further deterioration in trading conditions or the removal of support measures. Survey evidence indicates that about one-quarter of small businesses currently receiving income support would close if the support measures were removed now, before an improvement in trading conditions.”

—Financial Stability Review October 2020, RBA

That last sentence is worth repeating: “Survey evidence indicates that about one-quarter of small businesses currently receiving income support would close if the support measures were removed now, before an improvement in trading conditions.”

At the time of writing, JobKeeper and JobSeeker are reducing; the default moratorium has ended, and those with deferred loans will need to roll them over. In 3 – 6 months’ time, all of these supports could be gone.

If conditions don’t improve, then small businesses will need to start closing down or reduce staff numbers

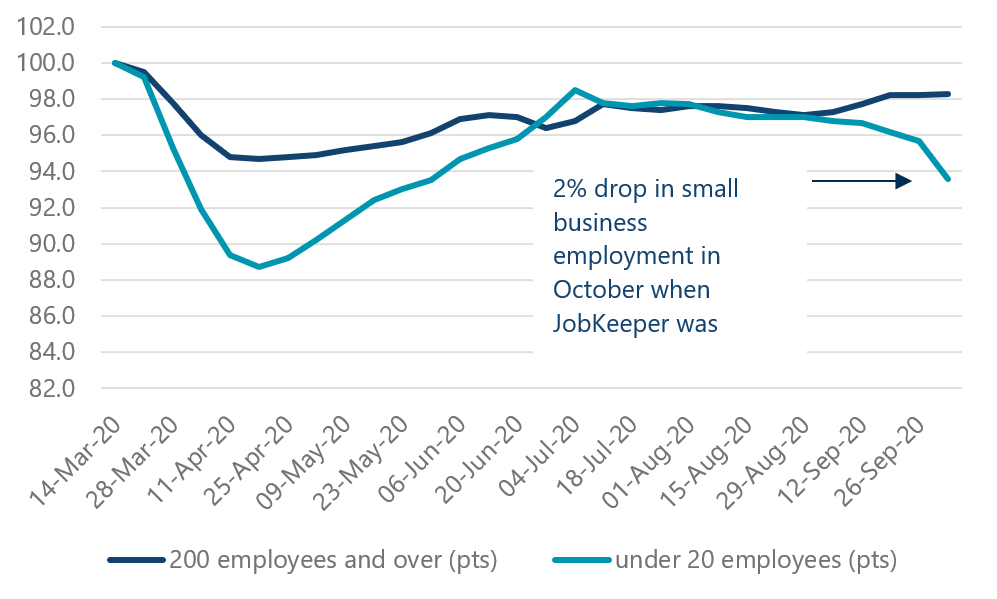

The flow-on effect from this is obvious: if conditions don’t improve, then small businesses will need to start closing down or reducing staff numbers. Recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) statistics seem to show this is already happening. When JobKeeper was reduced in October, there was a 2% reduction in small business employment, taking it back towards May levels.

Chart 4 – Employment by company size

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Nikko AM

While there are a large number of businesses operating normally despite the conditions, many are facing a high risk of closure. Looking at the RBA’s bottom 25th percentile of businesses, we can surmise that a large percentage of this group are related to tourism, travel and hospitality. This raises the obvious question in regards to business conditions improving—when will the Australian borders reopen?

A delayed reopening could pose a substantial risk to many of these companies. JobKeeper is scheduled to end in March 2021 and given that cases are beginning to spike in Europe, and the fact that the US has never been in control of the outbreak, the answer could well be that our borders will not be open for tourism until late 2021 or 2022.

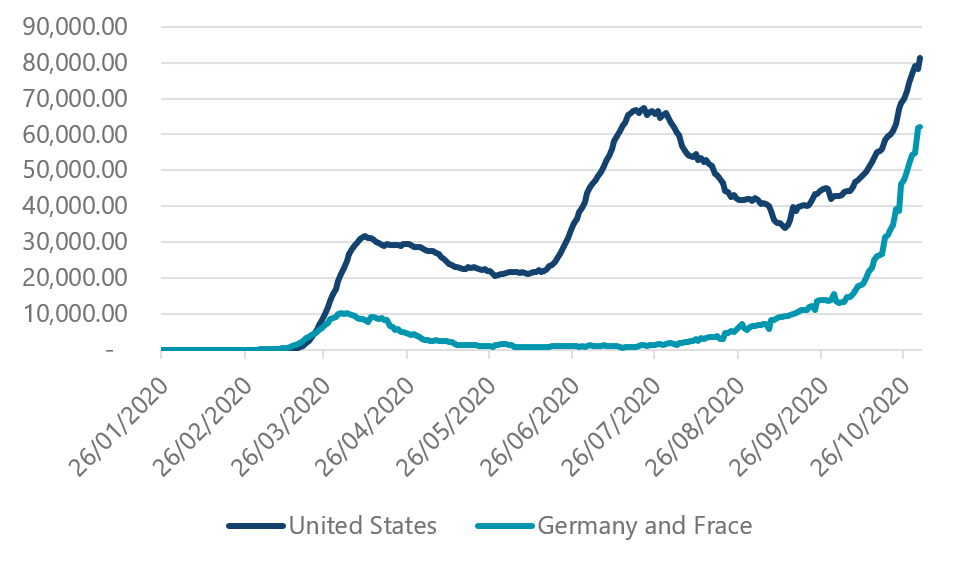

Chart 5 – New COVID-19 cases: Rolling 7-day average

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

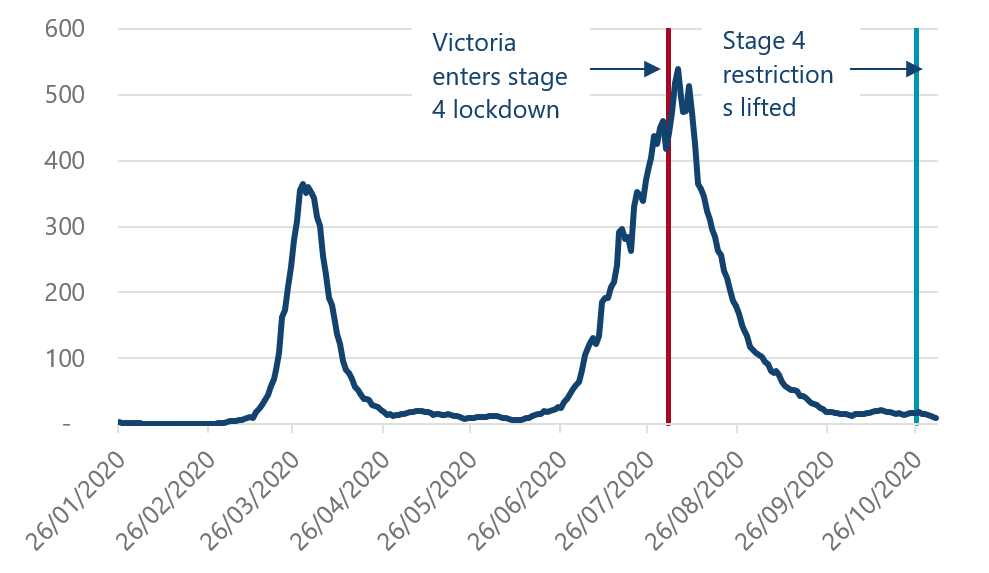

If we use Victoria as our yardstick to determine how long can it take to get this under control, the answer is months. In Victoria, cases peaked below one per cent of the daily cases in Europe and the US. Even with the strict lockdown laws, Victorians spent more than 80 days in lockdown before the situation was deemed to be under control.

Note: the contrast between the 500 rolling-day 7 cases in Chart 6 vs the 50,000+ rolling-day 7 cases in Chart 5.

Chart 6 – Australian COVID-19 cases: Rolling 7-day average

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

While there is still the potential that a vaccine could allow borders to reopen earlier, the RBA can’t rely on hope. The economy will need to do some heavy lifting over the next 3 – 6 months, and that means that small businesses in exposed sectors—those with the woeful interest coverage ratios shown in Chart 3—are going to need continued support. This is the uneven recovery.

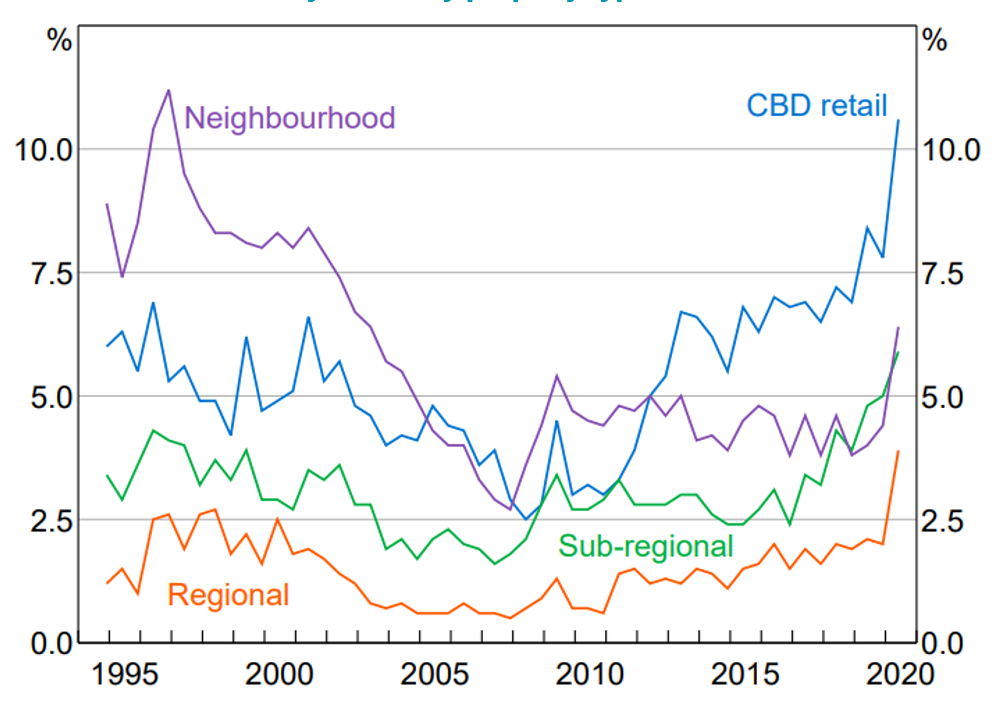

The other area that the RBA calls out is commercial property, particularly in the retail space. The below chart from the RBA shows that CBD commercial properties in the retail sector have over 10% vacancies, with all of the other sectors rising too.

Chart 7 – Retail vacancy rates* (by property type**)

Source: Financial Stability Review October 2020, Reserve Bank of Australia. *Vacancy rates for specialty stores. **Regional centres are anchored by department stores, sub-regional by discount department stores and neighbourhood by supermarkets

Here is the RBA’s comment confirming this could still get worse:

“Vacancy rates for commercial property are rising, putting pressure on commercial landlords… Further increases in vacancy rates are likely and department stores have accelerated planned closures… Demand for office space is expected to decline in the near term given staff working from home and reduced economic activity.”

—Financial Stability Review October 2020, RBA

As the RBA mentions, there is an additional risk that commercial office space in the CBD starts to see rising vacancies as well. As companies realise that part of their workforces can effectively operate from home, the need for floor space could reduce. Some of the major banks have indicated they are contemplating reduced floor space, with a news report in the Australian Financial Review claiming Westpac is thinking about the idea:

“Less is more: Westpac considers downsizing at Barangaroo”

And so the RBA must also keep a watchful eye on commercial property. While it seems to be fairing okay, the same cannot be said for the outlook.

The impact on vacancy rates is just one example of where you can see unevenness, but there are many other areas where you see a similar result: the percentage of the home loan market on deferral (~6%) and the fact that unemployment has hit 15 – 35 year olds the hardest. These types of risks are what the RBA needs to guard against. While it might not necessarily be the aggregate, there is the potential for risks coming from certain segments of the economy.

Despite the RBA improving its forecasts compared to a few months ago, this does not mean that it is wrong to be adding support. The ‘uneven’ nature of the recovery could take a very long time to correct itself and as employment support is removed, those businesses most impacted by COVID-19 will need support.

Q3 – What about financial stability?

Typically when thinking about financial stability, central banks will be concerned about making conditions too easy, which could lead to excessive risk taking, asset price bubbles or rampant inflation. But the RBA has clearly stated that their usual concerns have shifted. Here is how Michele Bullock (Assistant RBA Governor responsible for financial stability) described financial stability late last year:

‘”While we at the Reserve Bank do not have responsibility for the supervision of financial institutions, we do have an important role in monitoring the financial system as a whole and the economy for financial imbalances that could lead to instability. We typically look at such things as developments in financial markets, and, in particular, evidence of excessive risk-taking behaviour, the balance sheets of financial institutions and their resilience to changes in economic circumstances, and household and business balance sheets. Part of our role is to draw attention to potential risks that might be building and have an impact on the stability of the financial system.”

—Financial Stability Through the Lens of Business, August 2019

This statement highlights how the RBA monitors the financial system to determine if unnecessary debt is building up. However more recently Phillip Lowe pointed out that at the moment the risk to financial stability is not excessive risk taking, it’s the ability of borrowers to repay their debts.

This creates a much longer runway to ease rates

A second issue is the possible effect of further monetary easing on financial stability and longer-term macroeconomic stability. This is an issue that we have paid close attention to in the past when we were considering reducing interest rates in a relatively robust economic environment. It remains an important issue today, but the considerations have changed somewhat. To the extent that an easing of monetary policy helps people get jobs it will help private sector balance sheets and lessen the number of problem loans. In so doing, it can reduce financial stability risks.”

—The Recovery from a Very Uneven Recession, October 2020

This describes an RBA that is focussed on ensuring that rates remain low to help borrowers meet their debts. This means the RBA can be more aggressive than they usually would, as the argument for financial stability is flipped on its head—the risk isn’t that rates are too low; rather, that they are left too high.

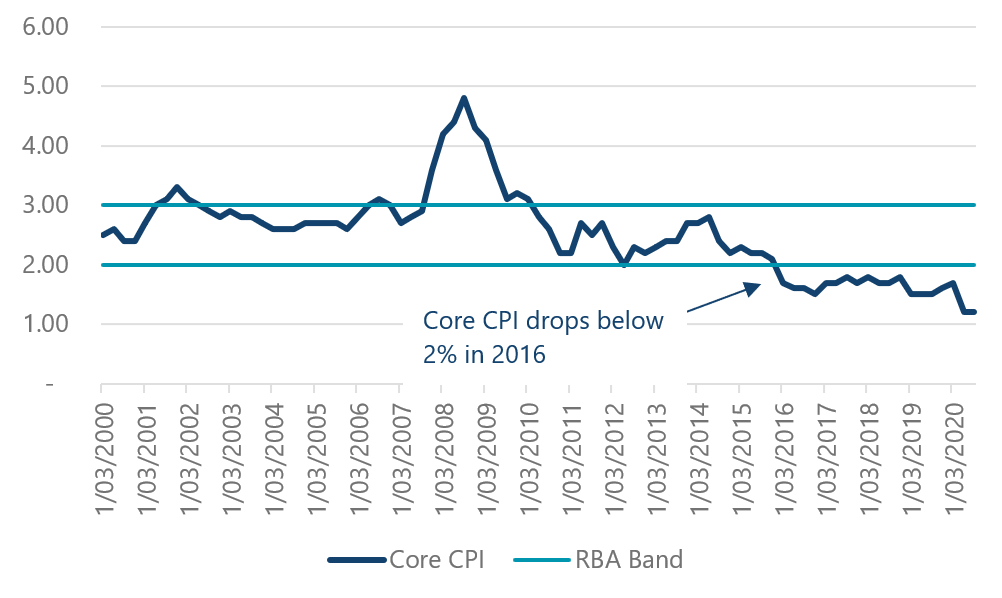

For a central bank that has missed their inflation target for the past four and a half years, and has unemployment rate at close to 20-year highs, this creates a much longer runway to ease rates without being concerned about bubbles—especially coming from an RBA that has told us that employment is a key concern:

“The Board views addressing the high rate of unemployment as an important national priority. It will maintain highly accommodative policy settings as long as is required. “

—RBA Monetary Policy Decision, October 2020

Chart 8 – Australian core CPI

Source: Bloomberg

Chart 9 – Australian unemployment

Source: Bloomberg

We believe the shift in the RBA’s thinking on this issue comes from the slow unwind of fiscal support for the household sector. As JobKeeper and JobSeeker are removed, the RBA will seek to ensure that they can mitigate the financial stability concerns of the borrowers potentially defaulting. Inflating asset price bubbles when the economy has had its largest contraction in decades is obviously the least of its concerns.

Q4 – The Prisoners Dilemma: Who cares what other central banks are doing?

The final question is to look at whether the RBA has come to the realisation that they can’t be the only central bank that does not use unconventional policies, as it will work against the economy. Put simply, if every other central bank is doing QE apart from us, then our interest rate curve will remain steep and the Australian dollar will start appreciating. Both of these will make economic conditions tighter and jeopardise our recovery.

Here is the statement that nodded to the RBA taking more notice of those offshore:

‘A third issue is what is happening internationally with monetary policy. Australia is a mid-sized open economy in an interconnected world, so what happens abroad has an impact here on both our exchange rate and our yield curve. In the past, the interest differentials provided a reasonable gauge to the relative stance of monetary policy across countries. Today, things are not so straightforward, with monetary policy also working through balance sheet expansion. As I noted earlier, our balance sheet has increased considerably since March, but larger increases have occurred in other countries. We are considering the implications of this as we work through our own options.’

—The Recovery from a Very Uneven Recession, October 2020

Another shift coming from the RBA is that they need to look at the effects of monetary policy offshore to determine how that can affect our relative position. In our opinion, this should not have changed over the past six months, as the impacts of easier policy offshore has been talked about for years. However, given the COVID-19 crisis globally is persisting longer than some had thought, perhaps this means the RBA is settling in for the long haul and taking more notice of what the policy differentials could mean.

Final point: How long could this last?

This commentary from the RBA really helps clarify why they are now shifting to a position of additional easing, which can be summed up by four ideas:

This low interest rate period could last 3 years and an argument could be made for 10

- Monetary policy should be more effective now businesses are reopening.

- The recovery of the economy will be extremely uneven and some sectors will require significant support.

- The usual arguments around financial stability are not particularly relevant at this time.

- Everyone else is doing it.

Which brings us to the final point: just how long could this low interest rate period last? At the moment, this is an extremely hard question to answer but, simply speaking, it should be at least three years and an argument could be made for 10. The RBA at least agrees with the shorter end of the time frame.

‘Given the outlook, the Board is not expecting to increase the cash rate for at least three years.’

—Monetary Policy Decision, November 2020

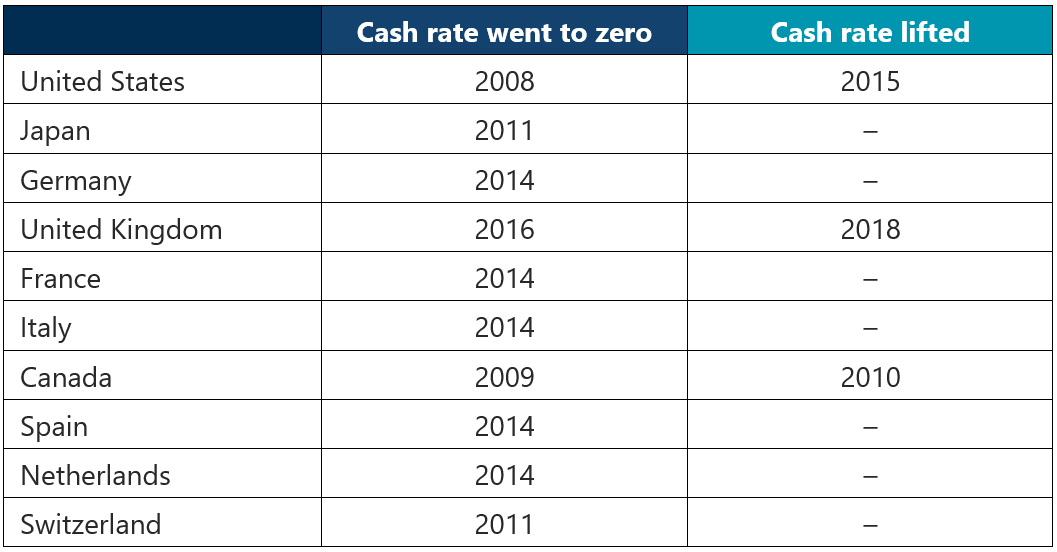

Without getting into the specifics of how long an economic recovery could take, let’s look at the experience of the 10 largest developed markets that have cut rates to zero.

Table 1 shows that Japan and other European countries that cut to zero have not been able to get off zero rates (and in some cases went negative). Japan and Switzerland are approaching 10 years of zero or lower rates, while the Eurozone will soon be approaching their seven-year anniversary.

Table 1 – Cash rates to zero (and back again?)

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

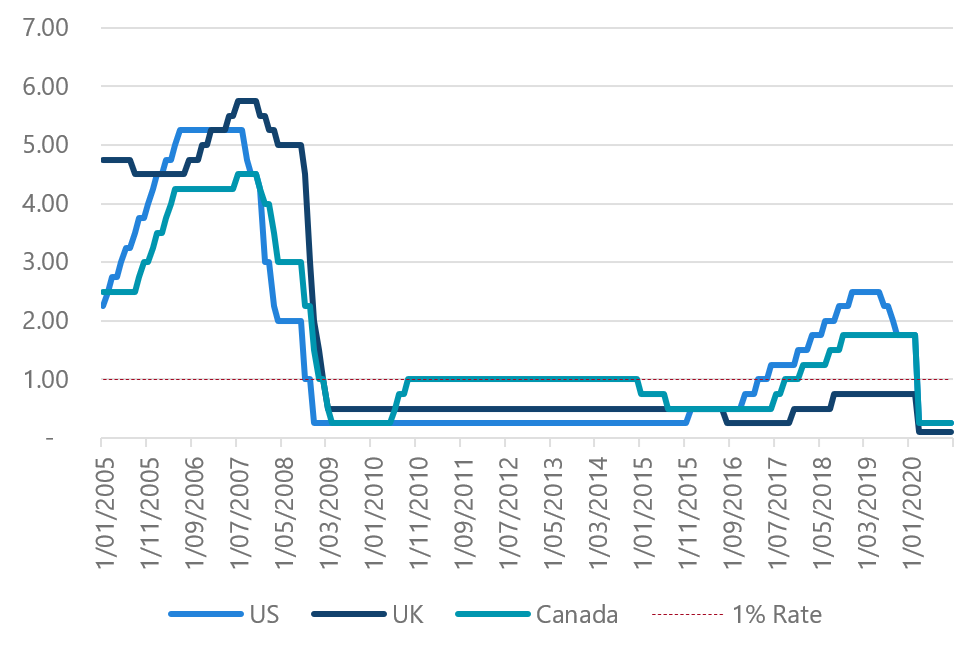

For the countries that could get off zero (US, UK and Canada), the zero rate experience was short lived for the UK and Canada (about two years each), but was close to seven years for the US. Chart 20 shows the cash rate experience for these three countries over the past 15 years.

Chart 10 – Comparison cash rates: US/UK/Canada

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM

There are a few points worth noting here. Firstly, for the bulk of the past 10 years, cash rates across these countries have been 1% or lower. Secondly, while Canada (turquoise line) was able to get away from a zero cash rate in 2010, it was not able to push rates through 1% for seven years. Thirdly, while the UK (navy line) avoided a zero cash rates for some time, it ranged between 0.25% and 0.75% for 10 years. Finally, only during the 3-year period of 2016 to 2019 were rates able to rise meaningfully in Canada and the US.

When we look at this, even if Australia is able to avoid the fate of Europe and Japan, a compelling argument can be made that the cash rate will remain below 1% for 5+ years. And if it is anything like the US after the GFC, this should see the cash rate remain at the zero lower bound for 5 – 7 years.

Stay one step ahead of the crowd

We don’t have to rely on picking market direction to capture returns. Instead, we look for the best relative value between securities and sectors that will deliver consistent positive returns for investors. Stay up to date with our latest insights by clicking follow below.

1 topic

Chris is responsible for portfolio management, including portfolio construction and trading for various Australian fixed income portfolios including the Nikko AM Australian Bond Fund at Yarra Capital Management (Nikko AM was acquired by Yarra...

Expertise

Chris is responsible for portfolio management, including portfolio construction and trading for various Australian fixed income portfolios including the Nikko AM Australian Bond Fund at Yarra Capital Management (Nikko AM was acquired by Yarra...