5 experts demystify the 10-year bond yield

The U.S. 10-year Treasury note is arguably the most important bellwether of global financial markets, especially when it comes to inflation.

Inflation, interest rates and long-term bond yields typically walk in lockstep. If the market expects inflation, then yields and rates rise too.

At least, that’s what normally happens.

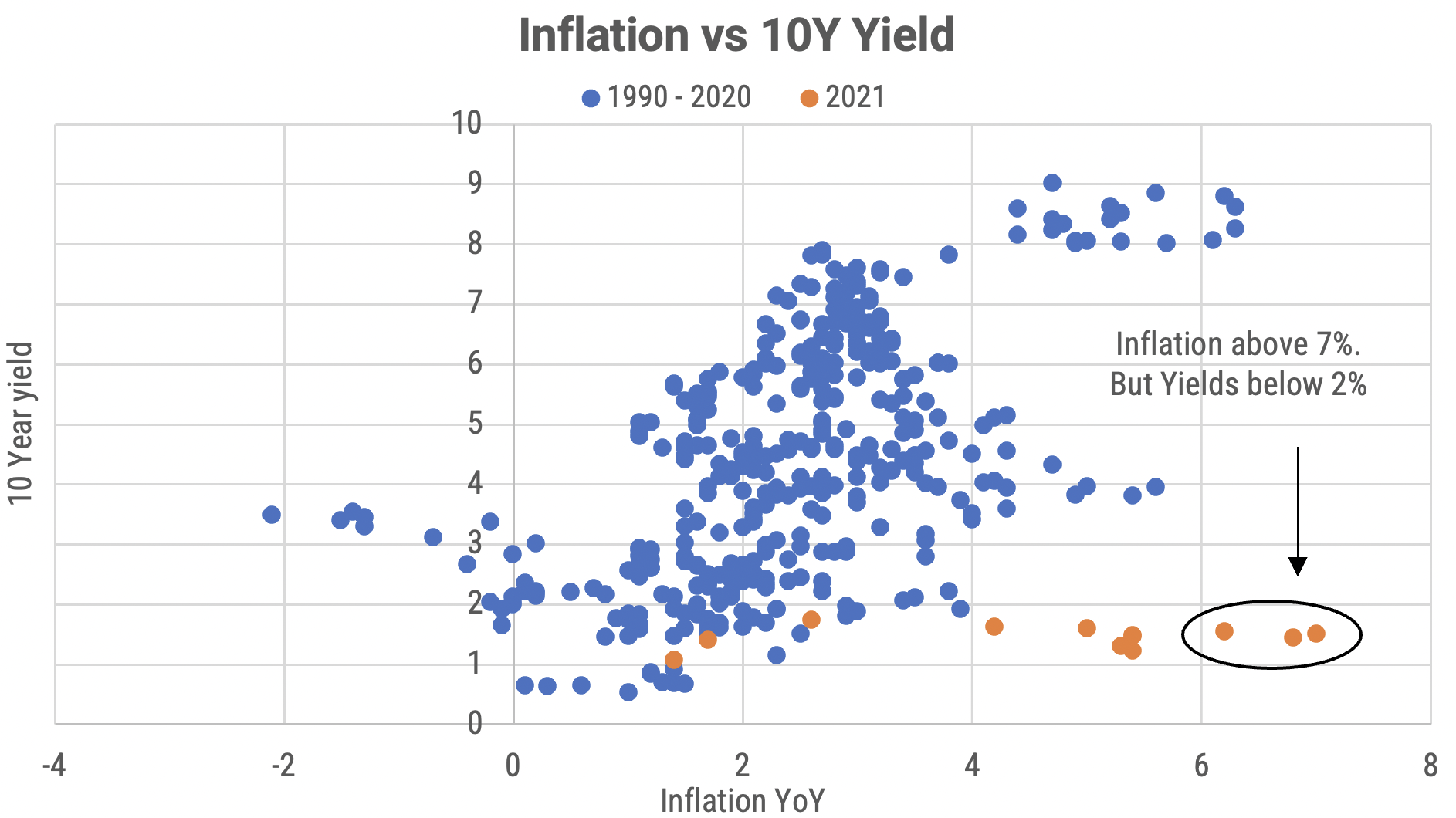

Despite headline inflation in the US hitting 7% in December, and core inflation at 5.5%, the yield on the 10 year Treasury note is currently sitting at 1.7%. That means that investors are willing to accept a negative real yield to hold government debt. Put simply, investors will pay for the privilege of holding government debt.

To try make sense of this we asked five experts to give us their reading of long-term bond yields, and what we can expect from markets in the coming months.

Don't be duped by fears of runaway inflation

Chris Siniakov, Franklin Templeton Investments

Contrary to the pop-culture like narrative that frequently dominates financial market news streams, the persistently low 10-year yield sends a very strong signal that runaway inflation is not likely to persist and, if anything, the structural drivers of global long-term yields – namely, ageing demographics, technological advances, excessive debt levels and globalisation – will reassert themselves as the dominant drivers of bond markets. If anything, almost all these structural drivers have strengthened in the last two years.

In addition to above structural drivers providing substantial headwinds in the background, the other main reason bond yields haven’t responded in a typical way to recent inflation is simply because they haven’t been allowed to. Financial repression works to keep yields low.

Central Banks and Government Treasury departments have come together this past two years to provide a post-war like response to the economic crisis. However, this de facto marriage between these two previously independent authorities and the unconventional (quantitative easing) policies are not healthy and will ultimately result in some significant market dislocations.

Take the Australian bond market in October 2021 as a micro example. The local bond market became unhinged as the Reserve Bank of Australia lost credibility in ability to maintain yield curve control in the short end of the curve. The resultant 90 basis point jump in yields from 0.31% to 1.22% is a level of volatility too high for your defensive investments.

Thank QE for the low yields

Alexandre Ventelon, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management

The US 10-year treasury yield has been undervalued against a number of key metrics in the current economic recovery phase for some time. The traditional relationship with macro indicators such as PMIs, cyclical versus defensive ratios, and of course realised inflation, have been pointing towards a much higher yield for months.

The current key difference in this economic cycle compared to prior cycles is the unprecedented level of monetary stimulus in the US. Morgan Stanley expects the Federal Reserve balance sheet will likely peak at around US$8.85 trillion in March, which is almost twice the peak in the previous cycle. In addition, this stimulus has been continuing at full speed while effectively the economy was already repaired.

These large bond purchases, along with the expectation the Fed would keep rates ‘lower for longer’, have kept a lid on yields and have prevented them from trading at fair value.

It was only once the Fed started to openly question its ultra-dovish stance following much higher than expected inflation prints that investors started to re-position for a gradual catch up in bond yields to fair value – and this adjustment is still ongoing. Despite US 10-year treasury yields having risen nearly 30bps since the beginning of the year, we believe this move is far from over. Morgan Stanley expects the US 10-year yield to end the year at around 2.3%, meaning there is still another ~50bps to go.

Markets could be taking a view that inflation pressures will be transitory

Frank Uhlenbruch, Janus Henderson Investors

High US headline inflation and low US long bond yields seem counterintuitive, especially if looking at past periods of higher inflation. When US inflation peaked in mid-2008, US 10-year government bond yields were around 4% and Australian 10-year government bond yields were 6.25%.

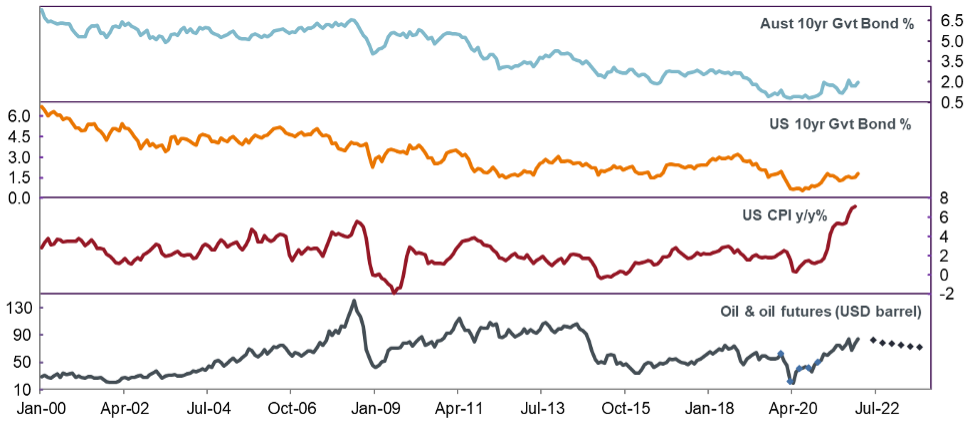

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg. As at 15 January 2022.

Around mid-January this year, with US headline inflation a shade over 7% and the US Personal Consumption Expenditure Core Price Index running at a 4.7% yearly rate, US 10-year government bonds were around 1.78% (1.89% in Australia), well below levels experienced during previous periods when inflation exceeded central bank targets.

There are several possible explanations for this. On the cyclical side, markets could be taking a view that inflation pressures will be transitory.

Supply chains that had been compromised by the Pandemic could be reasonably expected to recover over 2022 onwards.

Futures markets were pricing a modest fall in oil prices over the next 18 months.

On the structural side, global and domestic real rates remain very low reflecting the high demand for savings from an ageing population against relatively low investment demand, even after significant fiscal expansion.

On the monetary policy side, bond purchase programs, one of the central banks’ quantitative tools, have been acting to depress bond yields, providing both low risk-free borrowing rates and fiscal space for governments.

It's not whether Fed hikes, but what the final cash rate will be

Chris Rands, Yarra Capital Management

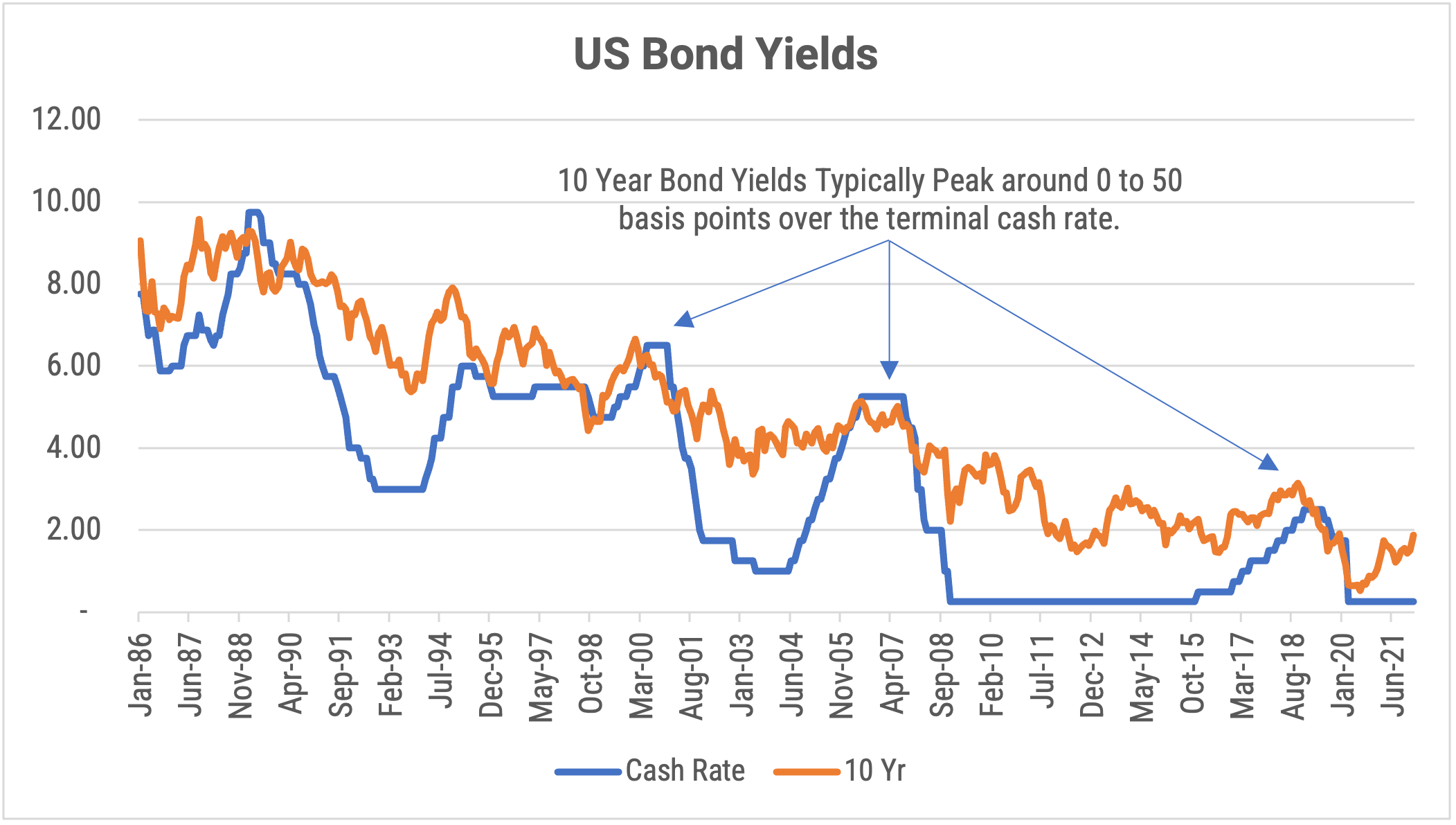

The recent sell-off in 2 and 10 year US Government bond yields points to expectations that the Federal Reserve should be hiking rates soon. This is particularly evident in 2 year bond yields, which have reached levels associated with the beginning of the 2015 hiking cycle. This tells us that the expectations from the bond market must be that inflation will remain above 2% and growth will rebound as we come out of another COVID malaise. As without these conditions, it is difficult to believe that the Fed would want to move rates.

Interestingly, even though inflation has risen to its highest level since 1982 bond yields remain relatively well behaved. We have seen multiple questions asking whether the 10 year yield should be considerably higher?

Source: Bloomberg, YarraCM

Our view is that it is important not to get too carried away when looking at how far bond yields can move.

Typically, the 10-year bond yield peaks at around 0 to 50 basis points over the terminal cash rate. This means to understand 10-year bond yields it is not only relevant whether the Fed hikes, but what will the final cash rate be.

Source: Bloomberg, YarraCM

Which raises the question: given inflation is 7%, why does the market believe there is going to be a short, sharp rate cycle?

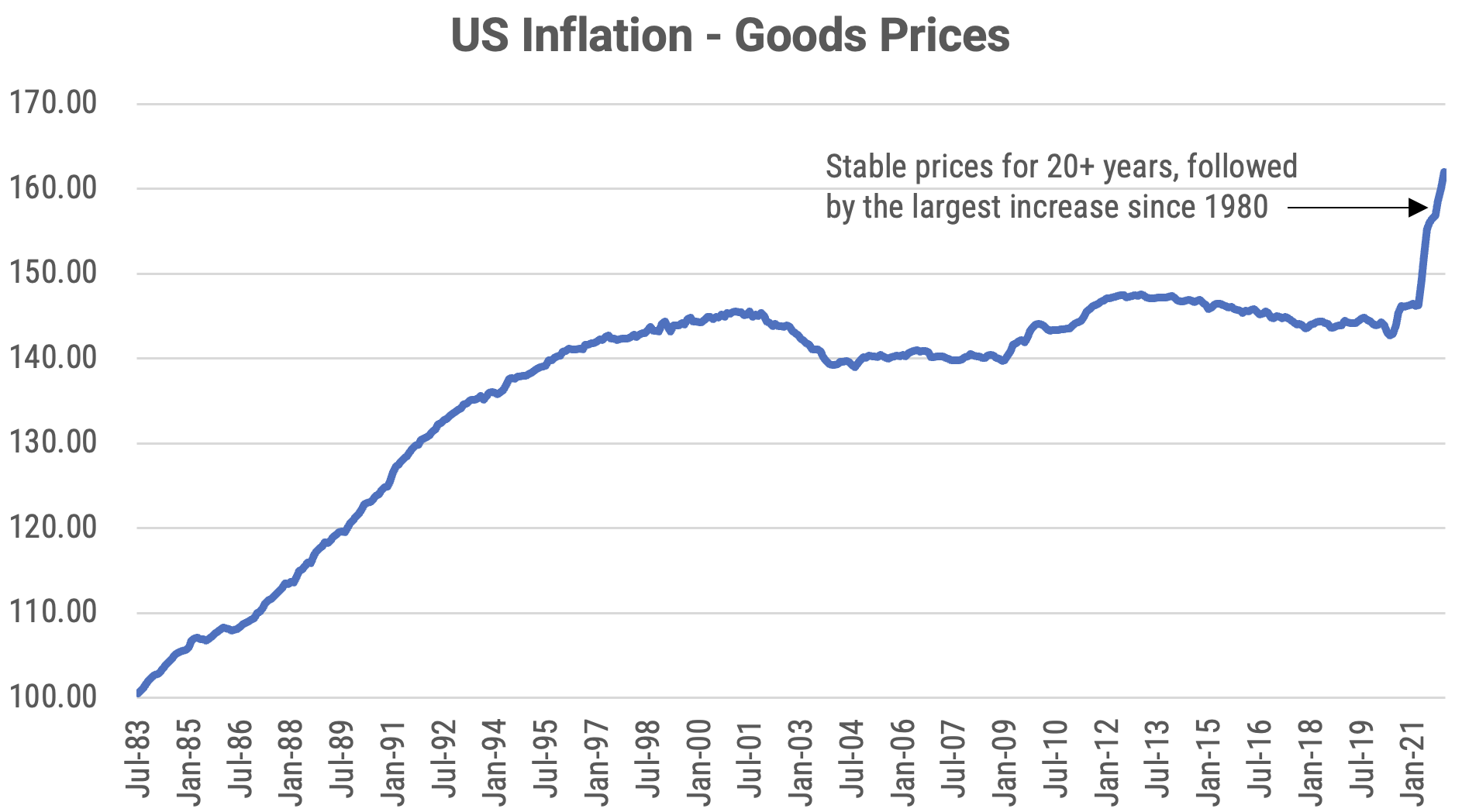

There are some nuances in the inflation data which question just how far rates may need to move to get a handle on prices. This is predominantly showing up in goods inflation, which after 20+ years of stable prices, has come to life by posting 10% gains. The chart below evidences just how out of the ordinary these price movements have been, requiring us to understand whether we are in a new paradigm for goods prices, or whether other factors are at play which will subside.

Source: Bloomberg, YarraCM

We see two factors at play which point to the current goods prices being short lived. The first of these are the supply chain issues caused by COVID, which were originally thought to be temporary and have now been lingering for almost 18 months. The below chart shows that as supply chain pressures increased, durable goods prices skyrocketed. As each wave of COVID seems to be handled better by the global economy than the last, we believe these pressures will eventually fall and take the heat out of goods prices.

Secondly, the huge amount of stimulus saw goods demand spike over the past 12 months, as consumers had more money and a limited ability to spend on services. As stimulus is withdrawn and economies remain open in the face of COVID, it would stand to reason that durables spending slows with a shift back to services. Accordingly, we expect demand will decline as the supply chain begins to resolve itself.

While goods prices have increased dramatically, services prices remain closer to their long-term average. This means that a normalisation of goods prices would quickly restore order to inflation data. While the past 18 months has shown that it can be difficult to forecast when these pressures will reduce, we find it interesting that the market now expects the impact on growth from COVID to be short lived, but the effect of inflation persistent.

Source: Bloomberg, YarraCM

We see the same forces impacting both economic factors, and that in time goods price will move back towards their 20-year trend. This suggests the Fed is not drastically behind the curve, but caught in tough circumstances where it is not clear whether rates is the appropriate tool to fix the situation.

Long term bonds selling off less than their short term peers

Kate Samranvedhya, Jamieson Coote Bonds

The current US Treasury curve is telling us that the bond market is pricing in the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) looking to hike up interest rates and lean towards Quantitative Tightening (QT) quite fast in 2022. Prior to June 2021, the long-end of the US Treasury curve sold off faster to price in higher-than-expected inflation data and a faster economic recovery. During the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) press conference in June, the Fed Chairman Jerome Powell mentioned the word “humility” to forecast inflation a few times. Since then, the yield curve turned flatter, which means that the front end of the curve, such as 2-year or 5-year bonds are pricing in more aggressive interest rate hikes, while the long-end of the curve, such as the 10-year to the 30-year bonds are selling off less than the front end.

Never miss an update

Enjoy this wire?

Hit the 'like' button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

2 topics

2 contributors mentioned