Avoiding the taper tantrum

|

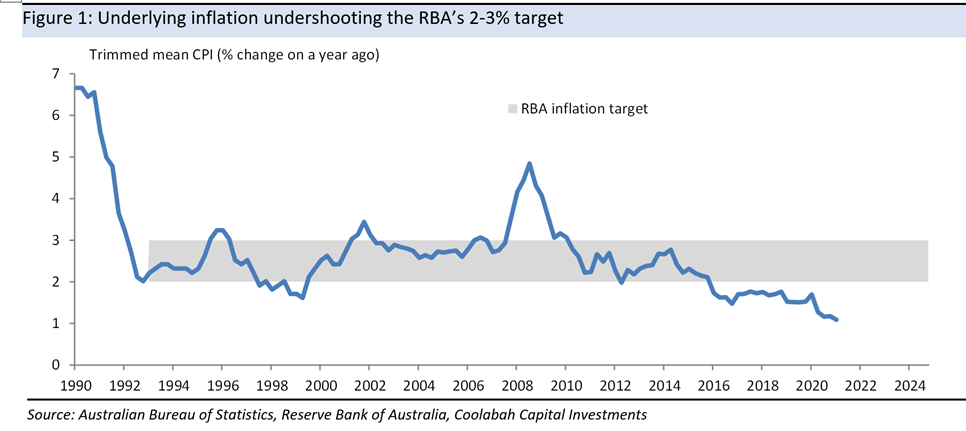

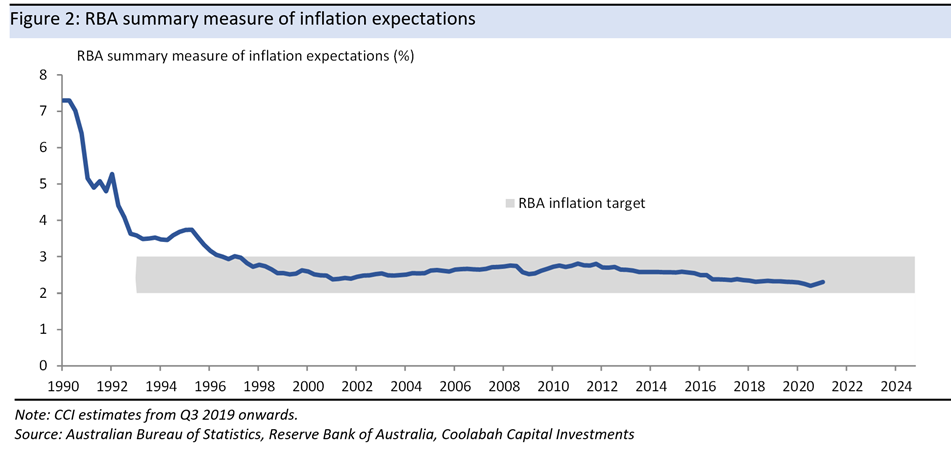

In the AFR this weekend I write that for all the inflation hype, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s challenge has been a persistent paucity of price pressures, and perhaps more worryingly, downward drift in inflation expectations. Excerpt only -- full column here: When the RBA’s erudite governor Phil Lowe assumed its leadership in 2016, he championed an important modification to the central bank’s implicit contract with the Treasurer, documented in the “statement on the conduct of monetary policy”. For the first time, this included a reference to setting interest rates to achieve the RBA’s policy goals, namely price stability, full employment, and prosperity, while accounting for “financial stability” risks. In his own research, Lowe had pioneered the important idea that a singular pursuit of price stability in isolation to other hazards, such as low interest rates driving a leverage-fuelled bubble in asset prices, could be sub-optimal for national welfare in the long-term. Around the same time, Lowe attenuated the market’s fixation with a specific 2.5 per cent inflation point estimate, arguing that “we have never thought of our job as keeping the year-ended rate of inflation between 2 and 3 per cent at all times”. And he disclosed a debate inside the RBA about the consequences of it failing to hit its inflation target: “Take the current situation of low inflation as an example". “Over recent times, we have considered the impact of our decisions not only on the future path of inflation, but also on the health of the balance sheets in the economy,” he continued. “Achieving the quickest return of inflation back to 2.5 per cent would be unlikely to be in the public interest if it came at the cost of a weakening of balance sheets and an unsustainable build-up of leverage in response to historically low interest rates.” In 2017 he expanded on these frictions, explaining that “in terms of the issues that we are considering, the unemployment rate is a bit high—it is not terribly high, but it is a bit high”. “It would be better if it were lower. The inflation rate is a bit low, and we would be closer to the target if it was a bit higher.” Lowe noted that “an argument could be made—and people argue this, including people on my own staff—that we could have lower interest rates today to try encourage a bit stronger growth in employment, get the unemployment rate down a bit and get inflation up a bit quickly. I think that is a respectable line of argument.” “The issue we are discussing internally is: how much extra fragility would that create in the economy? With household debt as a share of household income already at a record high, is it really in the national interest to get a little bit more employment growth in the short run at the expense of creating vulnerabilities which could become quite dangerous in the medium term?” Since 2016, however, the RBA has consistently undershot its inflation and employment targets, which has triggered more fundamental concerns that there may be structural changes afoot. This is in no way a criticism of Lowe and his talented successor, Guy Debelle: they have done an outstanding job, especially when faced with an existential, 1-in-100 year crisis, supported by an experienced board of leaders with deep policy and markets expertise, including Australia’s world-class Treasury Secretary, Steve Kennedy, former Macquarie Bankers Allan Moss, its long-standing chief executive, and wunderkind Mark Barnaba, a university medallist and Harvard MBA who is deputy chair of Fortescue, and the respected economist Ian Harper. There is nonetheless a worry that by (reasonably) shifting attention away from the artificially precise 2.5 per cent inflation point estimate, keeping policy artificially tight to moderate financial stability risks, and consequently under-clubbing inflation and employment outcomes for more than six years, markets might think the RBA is comfortable with, say, 2.0 per cent core inflation vis-à-vis the results between 1993 and 2016 that averaged right in the middle of its target 2 to 3 per cent band. Empirically, there has never been anything like the protracted core inflation misses evident in recent times: all the other breaches of the target band in the late 1990s, early 2000s and before the GFC were temporary affairs. One trader commented during the week that “prior to 2016, if the RBA forecast inflation below 2.5 per cent, we would be pricing in cuts”. “Yet today the RBA is projecting inflation prints well below the mid-point of its target band and we are pricing in hikes.” There is some evidence that the clear downward trend in core inflation has bled into expectations, which have both been decelerating since around 2014. Although the RBA’s inflation expectations benchmark remains within the target band, it has fallen from 2.5 per cent in 2016 to 2.3 per cent today. While this is not material, and could be completely transitory, it bears watching in a world in which the market thinks the RBA is more tolerant of downside misses. If employers and employees, for example, believe that inflation will remain stubbornly at or below 2 per cent annually, this will make it harder to normalise annual wage growth back to the RBA’s desired pace between 3 and 4 per cent. This brings us to a related tension: whether Martin Place should base policy decisions on its forecasts, which are notoriously difficult to nail, or practically shift to “nowcasting” and waiting until the hard economic data informs it of precisely where the economy stands. Traders are certainly very eager indeed for the RBA to “taper”, or tighten, policy on the basis of its highly uncertain projections of the future even though core inflation is running at 1.1 per cent, wages growth is near a record low of 1.5 per cent, and there remains substantial excess capacity in the labour market. Here there has been a pattern of the market wanting to doubt, or bet against, the RBA’s commitment to its stimulus. Some commentators have argued the RBA might be encouraged by the fact the Bank of Canada was able to reduce its own quantitative easing ahead of both the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank with no noticeable impact on interest rates or its exchange rate. They’ve also suggested that instead of nowcasting, the RBA would paradoxically switch to forecasting by hinging its July decisions on what the rubbery data in the two months of May and June signals about the RBA’s ability to help the economy back to full employment and sustainable inflation. Our research suggests this analysis is flawed. The Bank of Canada has tapered QE twice: in October 2020 and again in April 2021. After the October taper, Canada's nominal effective exchange rate appreciated 5 per cent. Since the April announcement, it has climbed another 4 per cent, which means the Canadian dollar is now at its highest level since 2015. At the same time, Canadian interest rates have lifted a material 18 basis points above equivalent 2-year US interest rates as the market prices in much earlier Canadian hikes. Any evidence of tapering in Australia would undoubtedly cause our exchange rate to similarly soar, detracting from economic growth at a time when our largest trading partner, China, is waging a brutal, one-sided war against many of our exporters.

|

1 topic