Bubble, bubble, tech and trouble

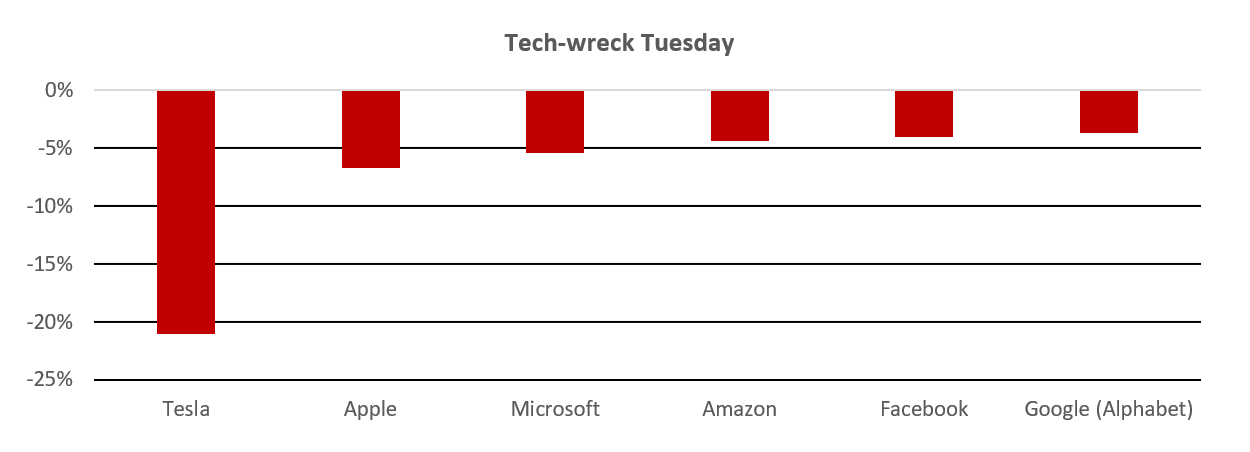

On 8 September, Tesla’s founder Elon Musk’s net worth plummeted US$16bn, the largest single-day loss for a member of the Bloomberg Billionaire Index. Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos also felt the pain, losing US$7.9bn. The bloodbath continued throughout the week, prompting us to consider the tech wreck of 2000/01.

Source: Factset, share price changes for 8th September 2020

During the late 1990s the internet created a huge sense of euphoria for businesses and investors alike and inspired high hopes for the online and connected future. With all the hype surrounding these businesses, investors assumed companies operating online were guaranteed winners and were going to be worth billions. Merely adding ‘.com’ to the end of a business was worth hundreds of millions in market cap.

Like all cases of extremes, this unconstrained euphoria ended abruptly with the burst of the tech bubble leaving investors facing very steep losses and several tech businesses forced into bankruptcy.

Between March and April of 2000, in less than a month, nearly a trillion dollars of stock value evaporated.

According to Bloomberg , during the 2000 Super Bowl, 17 dotcom companies paid US$44m for ad spots. The following year, there were only 3 companies left willing, or rather able, to pay for ads during the game.

There may be more to it than this, but three primary elements that lead to the burst of the bubble include:

- The use of valuation metrics that ignored cash flow. During the tech boom, many analysts focussed on metrics that had nothing to do with how the business generated profits. For example, the preoccupation with “network theory” which stated the value of a network increased exponentially as the series of computers hosting the network increased. What it fails to account for is the ability of the company to monetise this network and generate cash from it.

-

Hitting extreme valuations and overvalued stocks. When valuations avoid the anchoring of cash flow, they can reach any heights the new metrics demand. This includes referring valuation purely to eyeballs, revenue, or pro-forma EBITDAC (Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, amortization, and COVID; adjusted for stock compensation, and any other inconvenient nasties). Then as in now, it often appears the only limit to a valuation is the creativity to define a new measure. This is often justified with these ‘new age’ measures working……at least during the bull markets.

-

Crowding – during a bubble institutional, and retail investors, alike, often pile into the same sectors that are ’working’. Wall Street normally obliges by creating products to cater to the demand, whether that is new (active and passive) funds focused on the hot sectors, development of fractional stock ownership, zero commission trading, IPOs of companies in the favoured sectors and bullish research reports that explain why the situation makes sense. These powerful forces combined with observing the hot sectors continual ascent results in inevitable crowding in that sector. What “CIMQ” (Cisco, Intel, Microsoft and Qualcomm) stocks experienced during the last 1990s seems eerily comparable to today’s FAANGs.

Every bubble is different

The tech companies that are driving most of today’s global index return are made of stronger stuff than their ancestors in 2000. The 2000 tech bubble was made up of concept stocks that, in many cases, were no more than an idea on a PowerPoint presentation. The posterchild of the times was pets.com, which was incorporated in Feb-99, raised $82m via an IPO in Feb-00 and was liquidated in Jan-01. Today’s darling stocks are far more resilient, many of which are revenue generative and have viable business models. For example, Chewy.com (today’s darling pet ecommerce business), generates >$5Bn in revenue and is a real and sustainable business. However, that only tells part of the story. With a market cap of almost US$24Bn, it needs to be far more than just sustainable, we think it needs to generate far more meaningful profits and cash flow than its current EBITDA of $136m and breakeven FCF.

What we have now are some of the world’s largest, most profitable companies the world has ever seen

Since 2015, nearly all the S&P 500 gains came from four stocks. Facebook, Amazon, Alphabet (parent of Google), and Netflix (unlikely that Netflix was a key driver). These are wonderful businesses with seemingly uncontested growth, which has only been enhanced by COVID-related digital revolution. However, even wonderful businesses have a fair value, which should be anchored to something, with that something being FCF rather than optimism and stories.

Take Apple for example. The company’s enterprise value is US$2T, which is more than the combined value of the entire Australian and New Zealand stock-markets. Apple currently generates $73Bn in FCF growing 2% p.a. Based on these figures the payback on an investment in Apple is approximately 20-years. In a vacuum we consider this an unenticing return and more so when we consider the chequered history of prior dominant consumer hardware companies (Motorola, Nokia, and Blackberry). Can anyone truly say with their hand on their heart that Apple will continue to dominate its markets and generate growing FCF in 20-years from now? If not, you may never make your money back at all based on current valuations.

To be sure, we are not predicting the demise of Apple. We are simply stating that valuation matters, and history demonstrates that even market darlings can come back to earth. In the 1960 and 1970s it was the Nifty Fifty that ultimately succumbed to the gravitational pull of valuations, in the 2000s it was the CIMQ and today’s candidates are the FAANGs and related stocks.

The similarities - valuation methodology and extreme valuations.

For an active manager, conviction is crucial. This means adhering to fundamental principles regardless of the prevailing mood in the market, especially when the path of least resistance would be to simply follow the herd. In a recent post I emphasised the need to stick to your true valuation discipline and to stay away from “creating new valuation parameters to justify overpaying for a popular stock”. I feel this rings true in this case.

Changing valuation methodology, or looking for other metrics to justify a position, can be dangerous.

This was one of the key criticisms during the tech boom. Analysts were using metrics that ignored cash flows and these businesses ultimately went bust. This might not be the case with FAANGs, but the price you pay to own a business makes a difference.

Microsoft and Alphabet (Google) are great businesses, two business we held (~5% of NAV) up until August 2020. But the justification to owning these businesses wore thin as valuations rose, and with the surge in the large cap tech sector, we took the opportunity to lock in our gains and preserve capital. Even the best, highest quality businesses can lose money and they still carry risks. We now have no FAANG exposure in the Fund and as an active manager we will spend time searching for value elsewhere, across different sectors and countries.

Risks in the market, and in particular, the US, have been mounting. The ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncertainty surrounding the upcoming US election, the continued escalation in US-China tensions as well as the unknown end result from a promiscuous global monetary policy are examples of the challenges investors face. The potential biggest risk to tech is the arrival of a vaccine which might show the true resilience of this “new normal” digital-based world. Will people still want to do Zoom meetings? Will they still work from home most of the week?

The outcomes are hard to predict, but what we can do is take the experiences from the past and apply these lessons to the future.

We continually look to balance risk and return. In this case, the risks building up in valuations within the tech sector force us to seek returns elsewhere. We believe this is only possible for truly benchmark unaware investors. We are currently c90% invested in companies that we believe offer comparable growth prospects but with more favourable valuations.

Never miss an insights

Stay up to date with all my latest Livewire insights by hitting the follow button below.

3 topics

Joy manages the business and distribution strategy for Pengana's international equity division. She works closely with national business development team to enhance engagement with researchers, consultants, financial advisers as well as...

Expertise

No areas of expertise

Joy manages the business and distribution strategy for Pengana's international equity division. She works closely with national business development team to enhance engagement with researchers, consultants, financial advisers as well as...

Expertise

No areas of expertise