Burning down the house

Global Macro

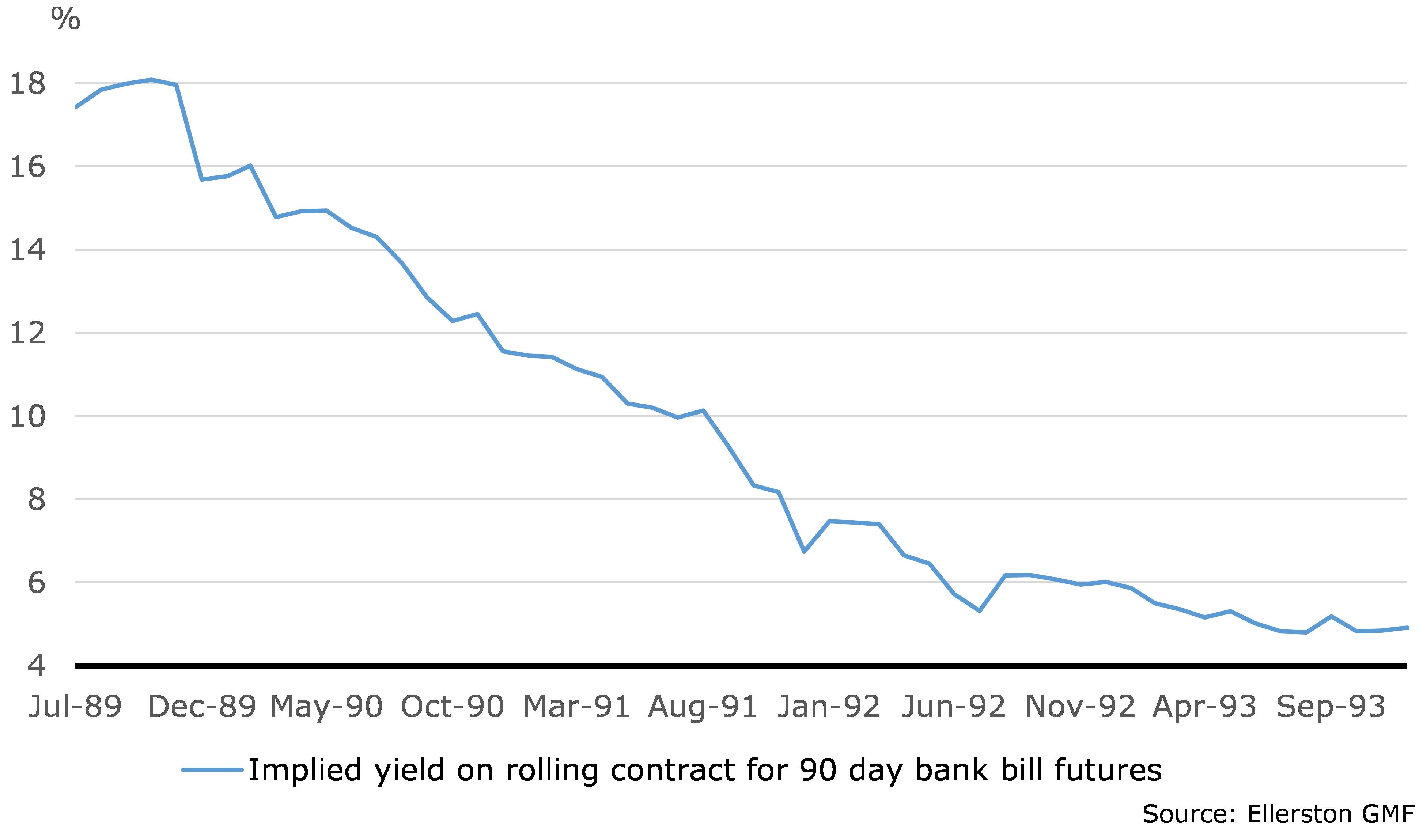

In 1989, I was hired by Bankers Trust as a graduate to work at the Sydney Futures Exchange. I pulled on the colourful jacket and went into the “pits”. It was heady and exciting times, and opportunities presented quickly. Within 6 months, I was trading the biggest book on the floor, shouting and screaming in the bank bill pit (1).

So here I am feeling super clever and super important, trading bank bills. But I was only good at execution. I really had no idea what was causing the prices to move. But moving they were. The RBA and Keating were working to contain a housing bubble, and interest rates were smartly rising to 18%! House prices had risen 50% in 1988 alone!

Meanwhile, my father had turned into a property speculator. My parents divorced in 1987, and he bought an apartment and sold it 4 months later for a 30% profit. How easy was this he thought? So he bought two apartments in Noosa and retired. Or at least so he thought.

In his lifetime, mortgage rates had been regulated. Prior to 1983, there were caps on credit, and mortgage rates had never gone over 13%. So he figured that was his worst case scenario. As they edged to 17%, he asked me what was going on. Were interest rates going to stop rising? When will they fall? What will happen to house prices?

Frankly, I had little idea. I was in the bank bill pit, so trading the 90 day paper based on the RBA cash rate (which in those day wasn’t even announced) and prices were swinging around 100 basis points a day. I had not developed my economic knowledge enough to have a handle on why rates were moving and where they were going over the medium term.

As we rolled into recession, Keating kept his foot firmly on the throat of the property market. Property prices starting falling. “It was the recession we had to have” he famously said. Needless to say my father was not a huge fan of Keating, despite my protestations (2). Cash rates were declining painfully slowly for him. He had to fold. He simply couldn’t afford the repayments. But prices were down 50% in Noosa! He went close enough to bankrupt.

By 1991, I was a proprietary trader for Bankers Trust. If I knew exactly what was driving rate decisions and where they were going, I would have advised my father to hold on, rates would fall quickly. Alas, my knowledge was gained too late to have advised my father.

Australia: 90 day bank bill future

Why am I relating this story? A consistent part of my outperformance over my career has come from correctly forecasting interest rates. So at the barbecue, when people come to understand this, the first thing they want to know is what is going to happen to interest rates and housing. Like my father did…

So here it is.

We think the RBA is going to start hiking by August, possibly May next year, and roughly do 2 hikes every 12 months. And house prices are going to go sideways to small up for a number of years.

That can’t possibly happen, they say; housing is already slowing, debt is too high, and prices will collapse.

So let’s first understand a few basics about Australian housing. The two most important drivers of Australian housing are

- The cost to service a mortgage

- The unemployment rate.

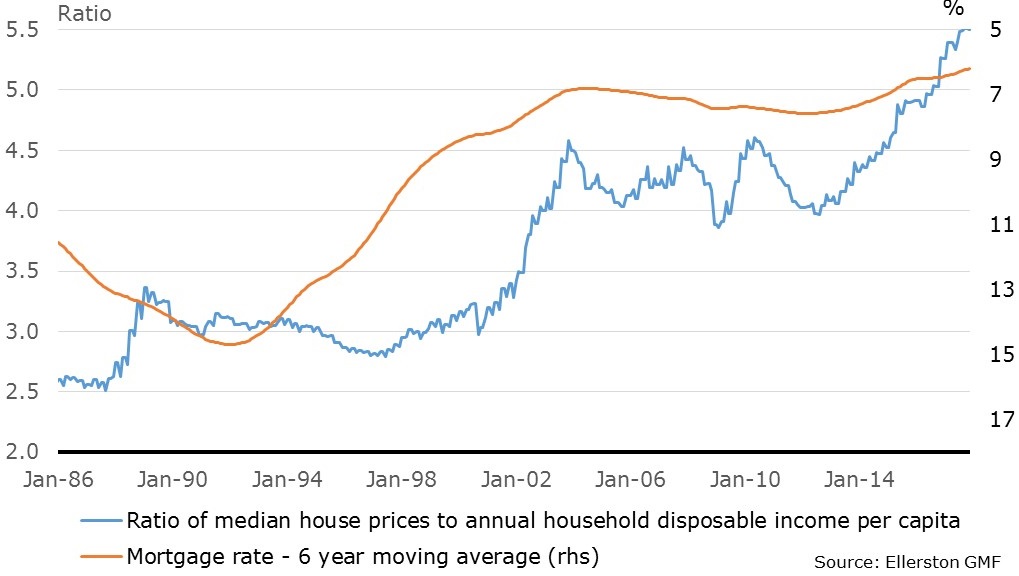

Notice I said the cost to service a mortgage. That is the repayment, and not the debt. People and the banks have to take debt into account in assessing how much the repayments will change, but at the end of the day it is all about the repayments. So when a borrower (and bank) sits down and considers the worst case on repayments, implicitly they decide what’s the highest the mortgage rate can rise too. My father thought 13%. Today most people would think 6-7%.

The thing is, this assumption changes relatively slowly. Each time there is a hiking cycle, the peak informs that assumption. The 1994 hiking cycle peaked at 7.5%. The 2000 cycle peaked at 6.25%. Wow, people realised, my mortgage repayments won’t ever rise anything like they did in 1990. I can borrow a lot more.

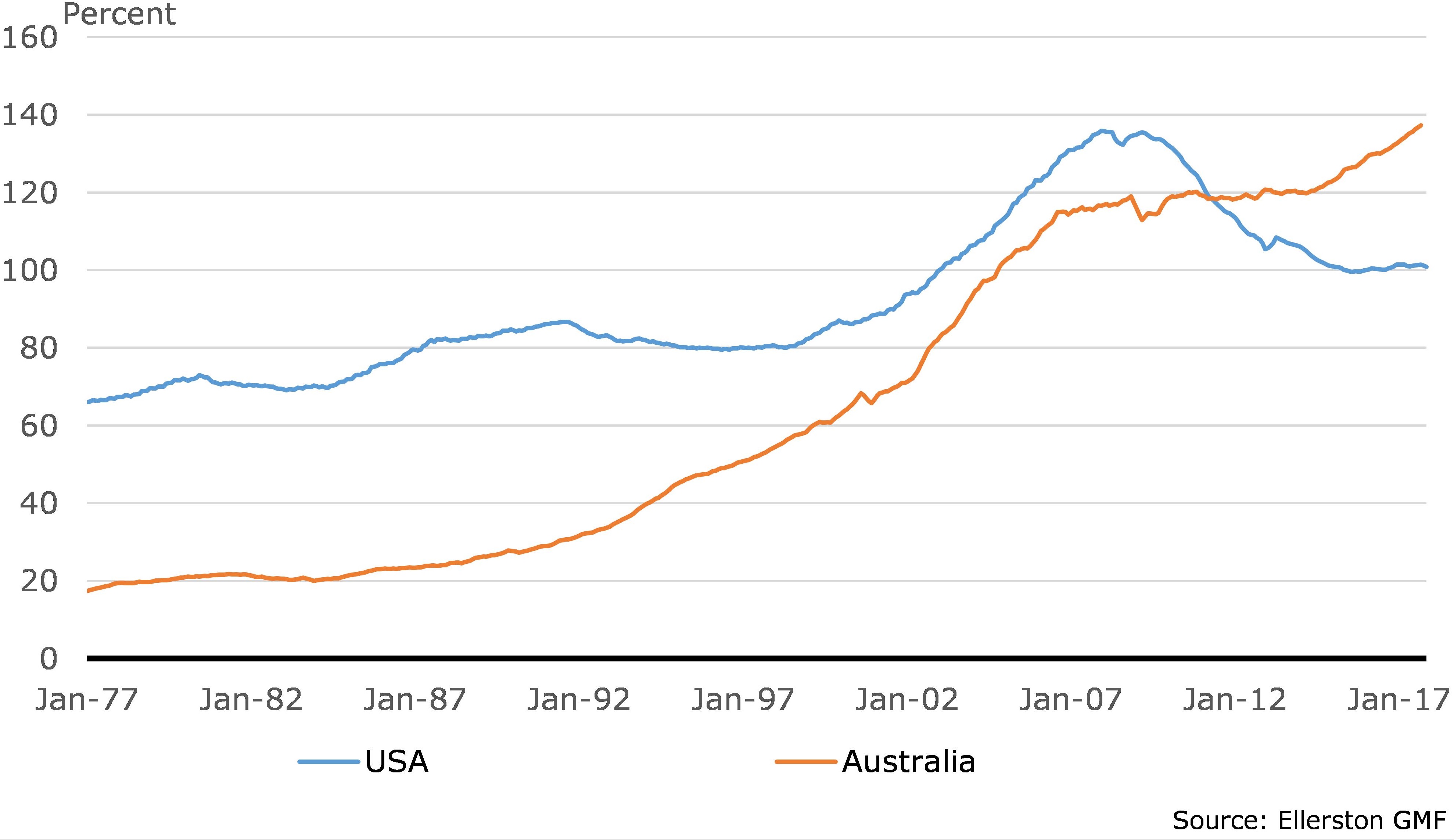

The RBA saw this coming. Indeed, they saw it as a perfectly natural development. In 1998, mortgage debt to income in Australia was around 55% (compared to 137% today). In the US, it was around 80%. In 1998 I was at a lunch with a senior RBA official, and I vividly recall him saying there was no reason housing debt/income in Australia shouldn’t be similar to the US. By 2002 it was.

Mortgage debt to household disposable income

So what does this mean? It means low (and stable) interest rates have been capitalised into property prices. Is that a problem? From a financial stability perspective, not at all, provided interest rates don’t go up too much, which they won’t.

House price to income and mortgage rates

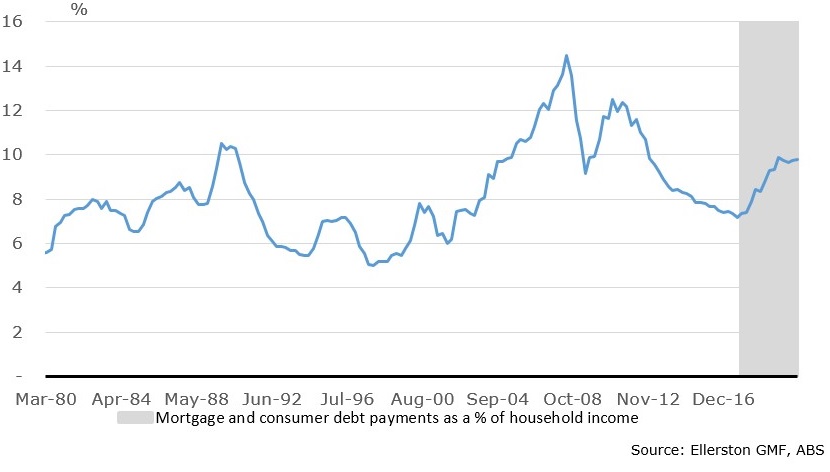

Why won’t they? Well the real efficacy of monetary policy is the impact on debt servicing. Leaning against the mining boom, interest paid as a % of income had to hit 15% to slow the economy (and the GFC intervened, so we are not sure how restrictive that would have proved). Post the GFC, 11.5% appeared enough, though again the European crisis intervened to stifle global growth.

We forecast 150 points of rate hikes over the next three years. That will take the debt servicing ratio to around 10%. Historically not onerous. Indeed, neutral over the last 15 years.

Australia: Household debt servicing ratio to disposable income

What might change that? Well immigration, and Chinese purchases, for sure. And more, or less, reliance on macro prudential tools.

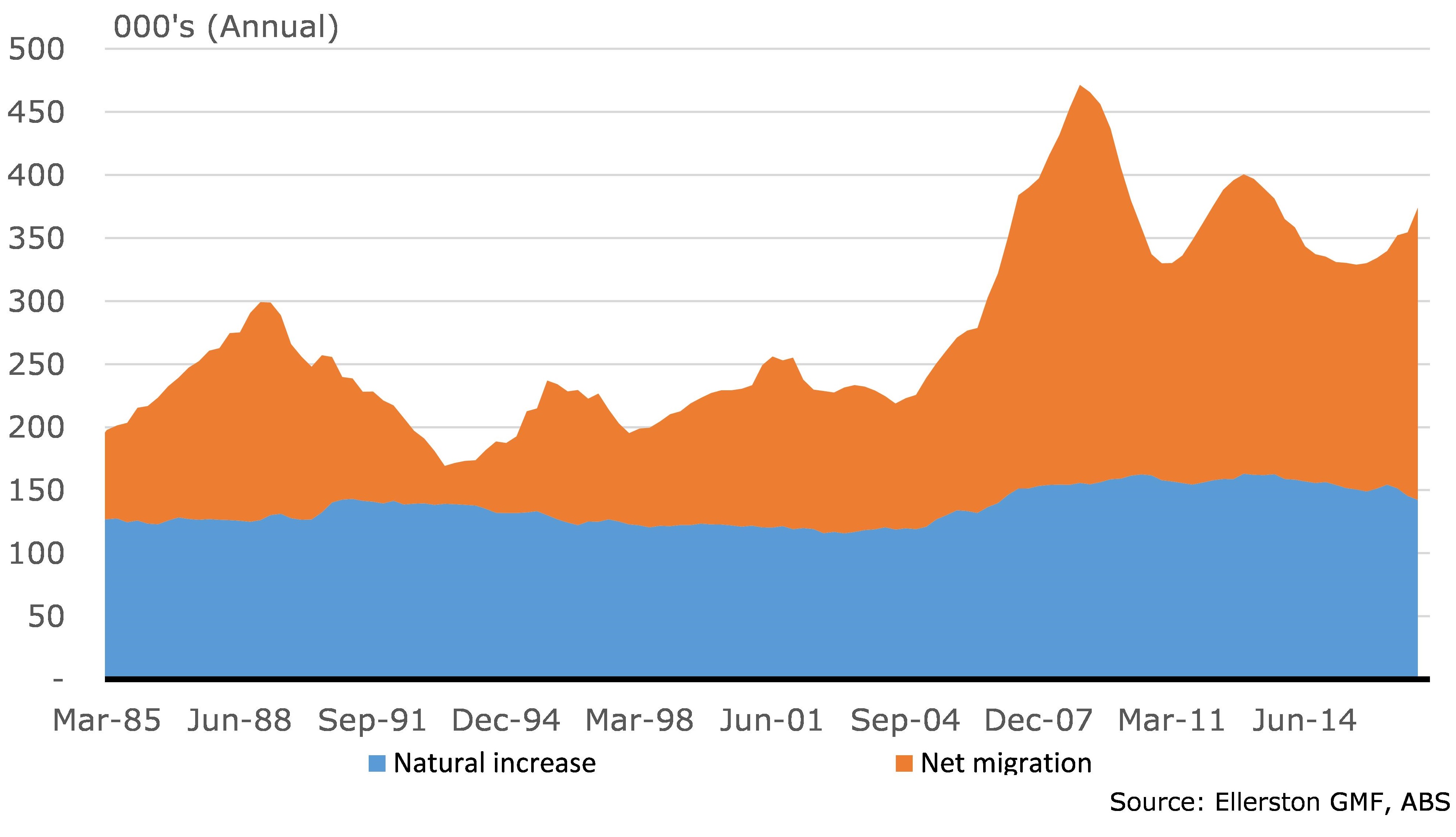

Immigration is the big swing variable in population growth, and is obviously controlled in large degree by the government. We have had a decade of exceptional strong immigration growth, and although it has faded through 2014 and 2015 it has recently reaccelerated. It looks like it will remain supportive, at least for the time being, whilst interest rates rise.

Australia: Population change

Chinese purchases? Well, given the improving wealth in China, some studies indicate Chinese purchases will increase 5 fold over the coming 5 years! However, governments globally are now leaning against this source of demand, and I would expect this to continue. If the impact is too large, expect more intervention.

So will house prices fall? The media is obsessed with doom and gloom stories, because that is what sells. Either house prices are rising too rapidly, or they are about to crash. I mentioned the other key factor, unemployment. Given full recourse loans in Australia, losing money on your house can wipe out all your wealth, as my father found. Hence Australians will do everything they can not to sell their house at a loss. They simply don’t sell unless they absolutely have to. Typically, that means when they lose their job. So the only time we have seen a meaningful fall in house prices in Australia is when the unemployment rate rises significantly. Otherwise housing turnover just drops.

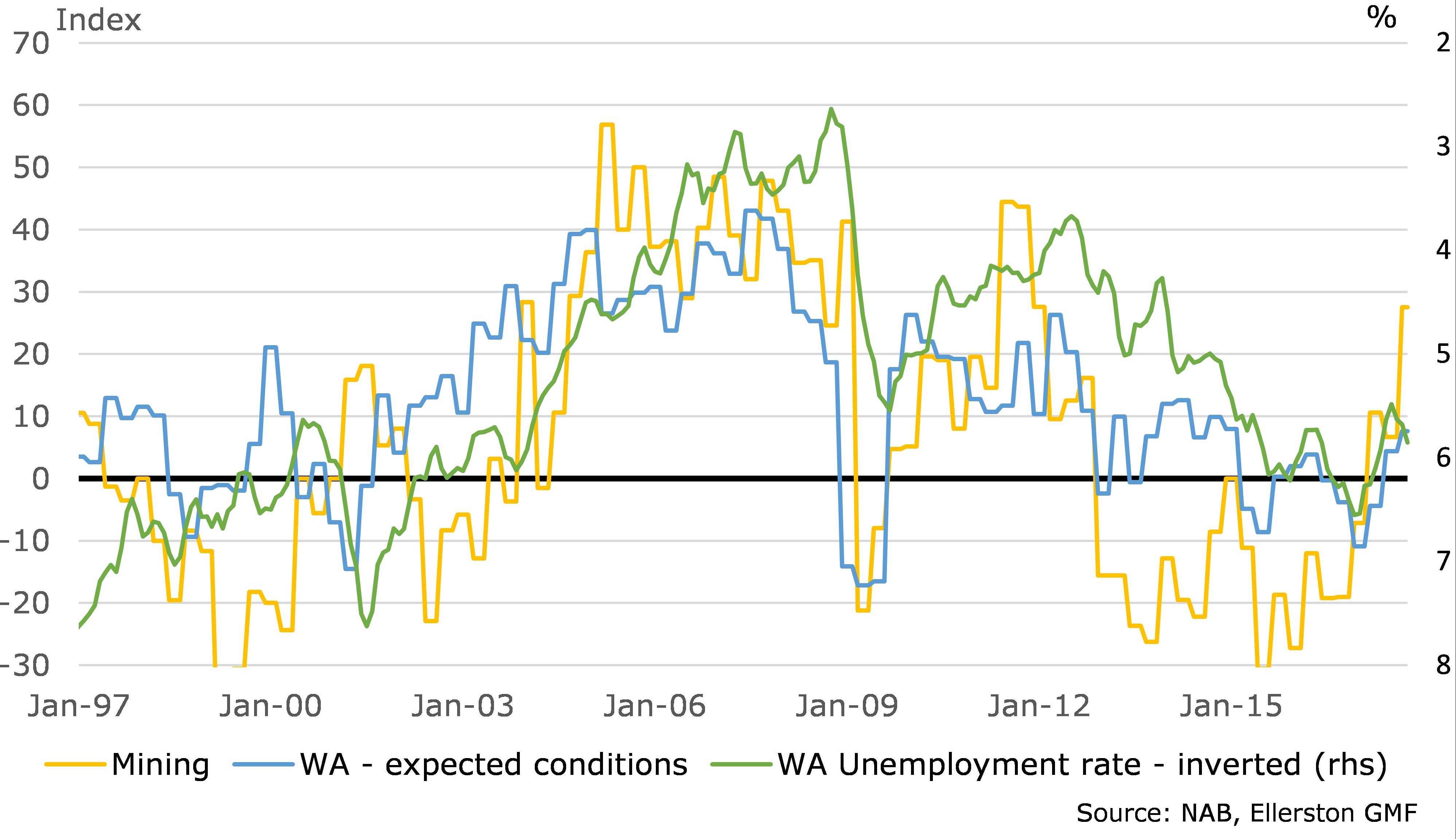

So why will interest rates rise? As George Bush learnt, “It’s the economy stupid”. Rates were set at 1.5% to support the economy as mining investment plummeted. They were intentionally set at 1.5% to fire the housing market to offset the slump in growth from mining investment, which hit WA particularly hard. But now WA is recovering, and so is the broader economy.

Western Australia: Business conditions vs unemployment

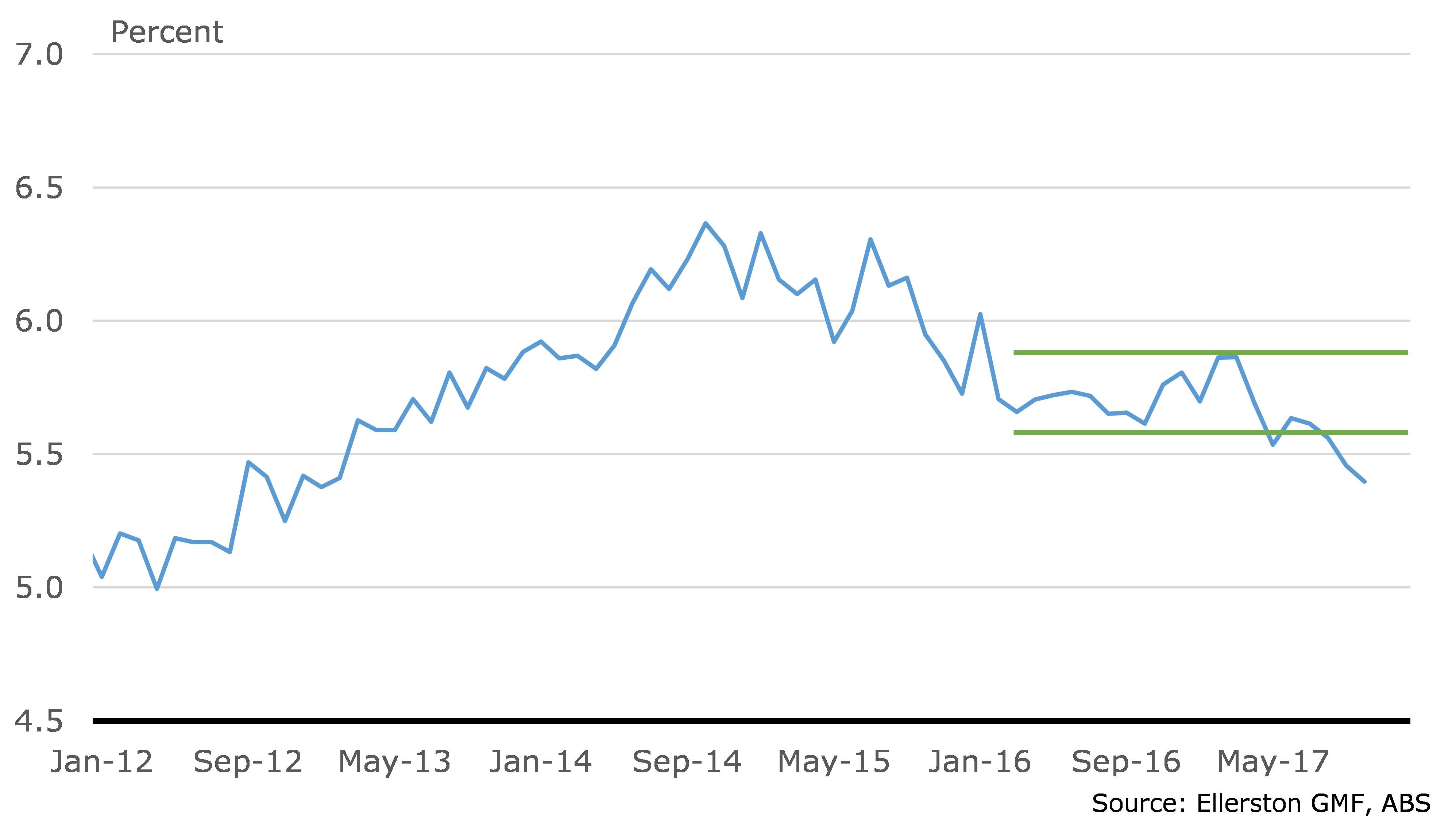

And this is manifesting itself in the Australian unemployment rate breaking its 18 month consolidation and starting to fall.

Australia: Unemployment rate

When this hits 5% the RBA will be hiking, or hiking soon. It’s the green light to ease back on super low interest rates as the mining states recover. We think it will hit 5% in 2Q18. The RBA sees a more muted decline, around 5.25% by the end of next year.

What about inflation? With 5% unemployment, they can confidently forecast inflation back to target in the medium term.

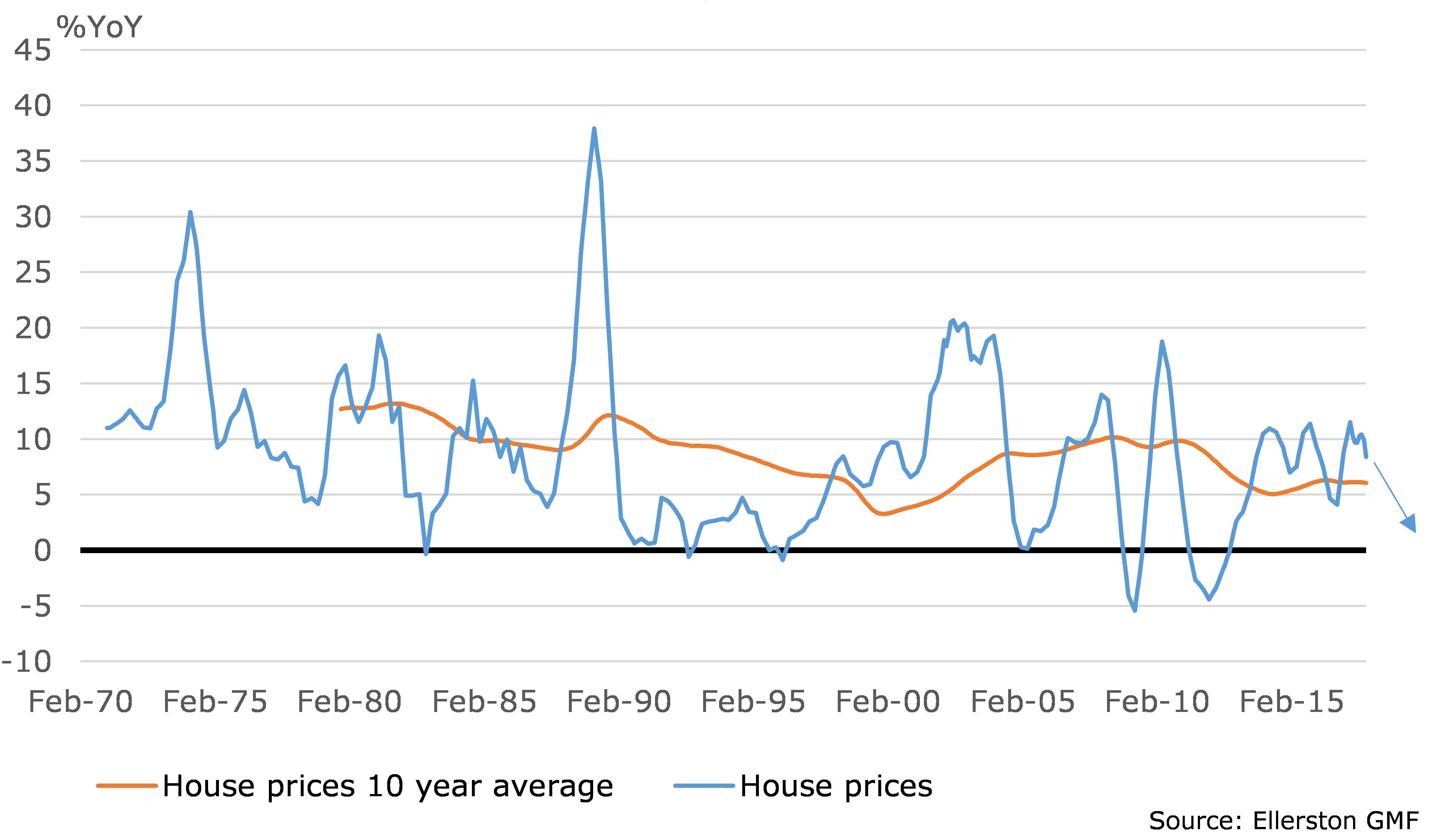

And housing? Think 2004-2005. Slower turnover, and muted price rises. Around 0-5% a year.

House prices

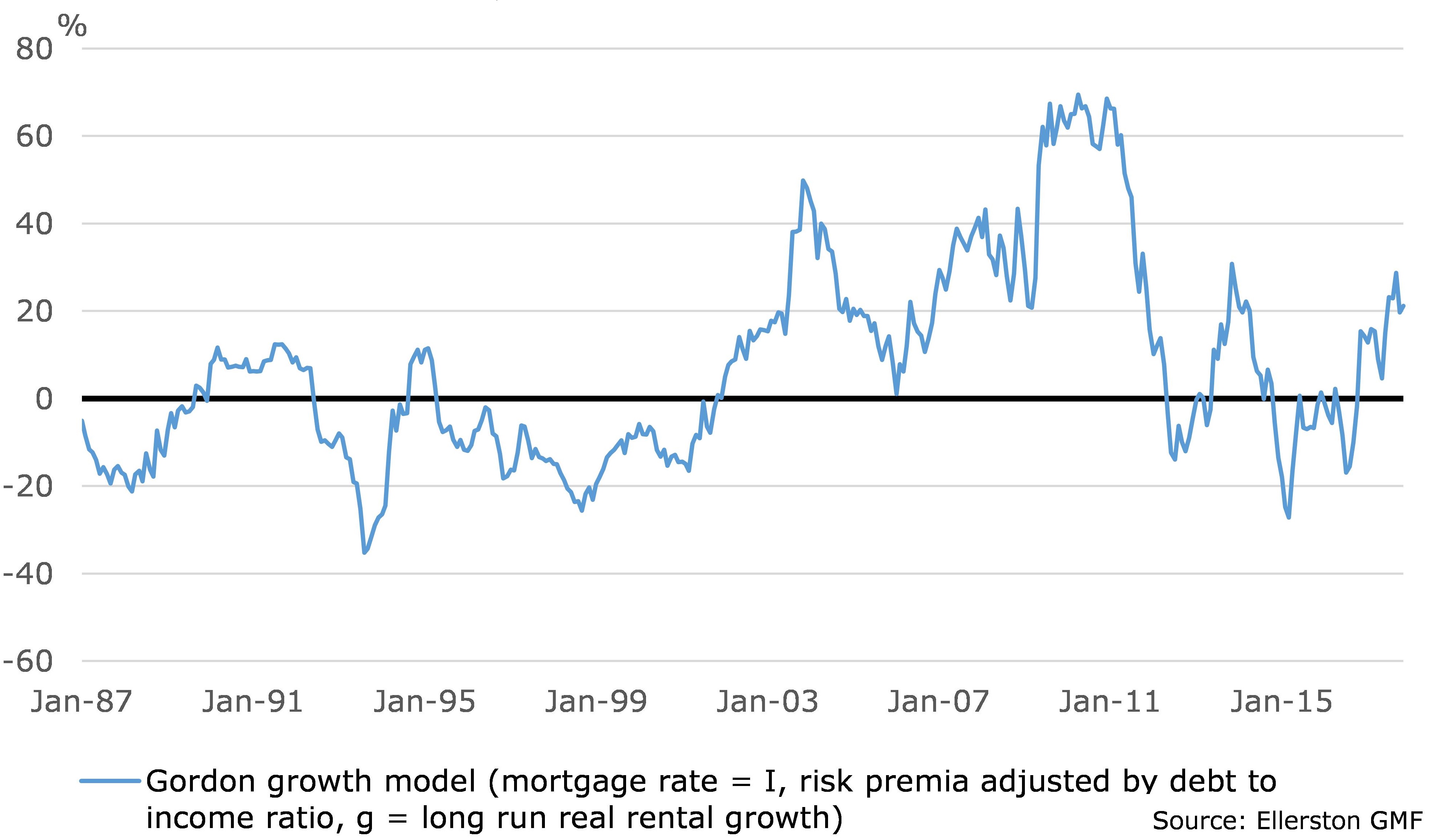

But isn’t housing a bubble? Won’t the bubble burst? Well actually not. Tim’s work see’s Australian house prices about 20% overvalued. Which is not high historically. And can be painlessly corrected with 0-5% price growth over a number of years.

House price over / under valuation

So what do I tell people now when they ask about housing at the barbecue?

Firstly, understand that the spectacular returns in property the last 25 years is almost entirely due to moving from a high inflation/high interest rate environment to a low inflation/low interest rate environment (3). Low rates have been capitalised into prices. It has happened. It won’t happen again.

Secondly, expect rates to rise, but only about 150 basis points to the peak of the cycle.

Thirdly, don’t expect a property crash, at least not until you expect a recession, which we don’t. Property prices are not a bubble about to burst. But it is also an asset class that won’t be a good investment.

To my children I say, buy a house for a lifestyle. Not for an investment.

For our portfolio, we are positioned for rate hikes in Australia next year. We have just started rebuilding this position in the last week and it is now the second largest risk position in our portfolio, after our US rate position (4).

About the Ellerston Global Macro Fund

The Ellerston Global Macro Fund is an absolute, unconstrained strategy investing in a number of fundamentally derived core themes, optimised via trade expression and portfolio construction across Fixed Income, Foreign Exchange, Equity & Commodities. It focuses on capital preservation while providing low to negative correlation to traditional asset classes. Find out more here.

Footnotes

(1) If you want an idea what it was like, watch “Trading Places” with Eddie Murphy. They capture it brilliantly!

(2) Keating’s policies, in particular floating the dollar and a flexible low inflation target originally enabled by the Wages Accord, did set Australia up for its world record expansion continuing to date.

(3) In the 1980’s the big driver of the property boom was the deregulation of the banking sector. Some argue that deregulation has driven the 30 year housing boom, particular Basle changes to capital reserves required for mortgages. I would argue the freely available credit allowed low borrowing costs to be capitalised into prices, not caused.

(4) Please refer to Oct newsletter for an outline of our US rate view.

2 topics

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.