Can you make money in fixed income in the age of The Zero?

Bond yields may have increased sharply last week, but fixed income investing hasn’t got any easier. A large pool of the market still yields next to nothing.

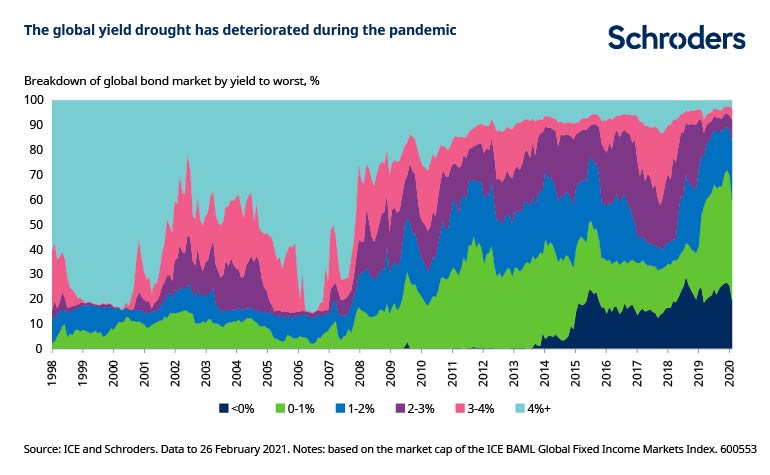

For example, as at 26 February, 60% of the global bond market traded at a yield of less than 1%, as shown in the chart below.

Low yields are a concern for investors because they can reduce long-term prospective returns. But that does not mean all hope is lost. Better outcomes are still possible. Here are some of the ways in which bond investors can potentially improve their return experience.

Ride the bond rally

Although yields are a reasonable guide to long-run future returns, they have very little predictive power in the short run.

Historically, starting yields for euro investment grade (IG) corporate debt (creditworthy issuers) have only explained 18% of the variation in subsequent one year returns. This means that very little of the year-to-year volatility in bond returns can be attributed to yield levels (see table underneath).

Why is there such a weak relationship over short holding periods? Well, the yield on a bond assumes the bond is held to maturity and that interest rates stay constant.

However, in practice investors may choose to sell a bond before its maturity date during which time yields may have fallen and bond prices have increased, resulting in a profit in the process.

Of course, this works both ways. Any rise in yields could lead to significant losses – as has happened recently.

In mathematical terms, if the yield curve is upward sloping, as it is at present, that means the market is pricing yields to rise over time. If yields fall, stay unchanged or even rise (albeit by less than is priced in), bond returns will exceed the starting yield. Low yields need not be an impediment to achieving higher returns.

For example, over the past five years, euro investment grade corporate debt traded at a yield of less than 1.0% on average and yet the annualised total return was 3.0% over that same period.

However, with euro corporate bonds already trading at a record low yield of 0.4% today, the potential for future yield falls is more limited. So what else can investors do?

Rolling down the yield curve, rolling up the return scale

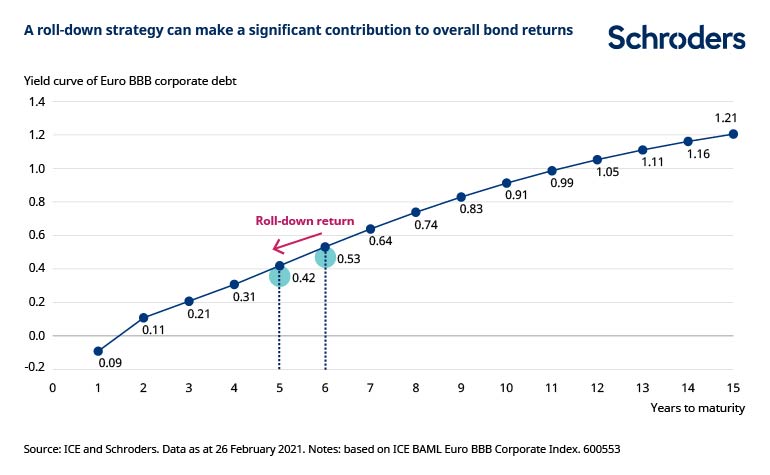

When the yield curve is upward sloping - meaning longer-term bonds trade at a higher yield than shorter-term bonds – a bond’s yield will decline with the passage of time, so long as the yield curve remains unchanged. As bond prices are inversely related to yields, this can lead to the bond’s price rising.

An example helps illustrate this. Let’s suppose you purchase a euro BBB corporate bond (the lowest rung of investment grade debt) with six years to maturity at a yield of 0.53%. Assuming the yield curve in a year’s time is the same as today, after one year that six-year bond will become a five-year bond with a yield of 0.42%. This is shown in the next chart.

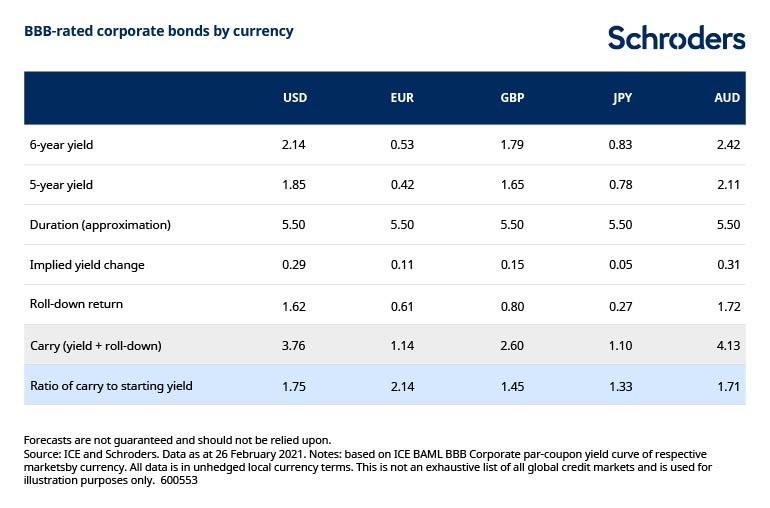

Multiplying the yield change by the bond’s duration (approximately 5.5 years in this example), which measures sensitivity to yield changes, implies a profit of around 0.61%. The total return is therefore 1.14% (yield/coupon income + roll-down return).

So if an investor now sells the bond, they could crystallise that gain and more than double their holding period return compared with what they would expect from the yield alone.

The same effect can be seen for other bond markets around the world, although the roll-down return will vary considerably given the different curvature of the yield curve.

For instance, assuming the yield curve stays constant, buying a six-year US dollar BBB corporate bond and selling it after one year would result in a roll-down return of 1.62%. This is greater than in Europe because the US yield curve is currently much steeper.

Of course, in practice, as recent movements in the bond market have shown, yields can sometimes dramatically increase and wipe out any profit resulting from rolling down the curve.

Dynamic asset allocation

If that’s not enough, then another thing investors could do is tactically adjust their holdings across different geographies, sectors and industries.

In general, the lower the credit quality, the higher the expected return since investors need to be compensated for the added risk.

However, credit markets are also prone to short-term dislocations, during which one segment may outperform or underperform for a period of time, as illustrated below (see asset class definitions here).

It is during these periods that investors can earn potentially higher returns provided they are free to invest and allocate actively over time.

Not all bonds are equal

As well as asset allocation across credit segments being a potential source of added value, the same is also true of security selection.

The US is home to the largest corporate bond universe in the world, but that does not mean all bonds rise and fall in tandem with the overall index.

For example, in 2020, the US investment grade market returned 9.8% but over half of its constituents performed even better.

Our research also found that, on average, environments in which yields increased have been a more fruitful hunting ground for alpha generation, as measured by the proportion of bonds beating the index.

Headline yields signal false sense of doom and gloom

It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that as yields have declined, the opportunities to make money have also evaporated. Yet, the truth is that investors have multiple levers at their disposal to enhance returns.

Although nothing is guaranteed, yields can always fall further, especially in regions where interest rates are not as depressed, such as the US or emerging markets.

Given that yield curves are upward sloping in all markets, even if yields don’t fall, returns can still exceed yields thanks to roll-down.

However, yields can sometimes rise sharply and hurt returns so it’s important to have a diversified portfolio as not all markets will be affected equally.

For example, if investors have the flexibility to diversify their portfolio globally or by credit rating, they can also take advantage of the significant variability in returns across and within each segment.

Whichever approach is chosen, owning core fixed income assets can still make sense in the age of The Zero.