No Country for Old Men

While investing may not quite evoke the tension of Cormac McCarthy’s story of Llewellyn Moss trying to avoid the sociopathic killer Anton Chigurh while the indefatigable Sheriff Bell tries to protect him, many of the themes seem relevant to equity markets and economies today. The old battles the new.

The new world in equity markets is one of systematic and passive investing setting market prices and technology scouring every report and transcript for indications of momentum and patterns in share price reactions, while portfolio construction is dictated by rules-based index purveyors (charging handsomely for selling simple calculations).

The new world in economies is seeing government intervention overshadow capitalism, government spending losing all connection to tax revenues and ever more dominance of asset prices in driving consumer behaviour as abundant liquidity increasingly disconnects them from fundamentals. No country for old men.

Active managers sit at the crossroads. Is there a value proposition for traditional thought and analysis or should we retrain as plumbers (some might argue we’ve been dealing in crap for years)? We are not the only industry facing these challenges as technology increasingly replicates human decision making (or at least the patterns of past decisions).

As productivity growth and GDP per capita stagnate across much of the western world, with Australia worse than most, the wisdom and sustainability of policies and interest rate settings which elevate asset prices and substitute speculation for work seem ever more important issues.

Generating productivity gain in service economies has been tough. Much as Donald Trump might choose to resist, taking the economies of today back to the past seems unwise and unlikely. Developed, high wage economies necessarily shed manufacturing capability to lower wage developing economies. Reclaiming manufacturing with high wage costs seems a tough way to improve living standards.

As we grapple with the question of whether artificial intelligence can replace vast swathes of white-collar employment and whether our living standards can continue to rise if we stop thinking and allow computers to do it for us, the future doesn’t seem obvious. The inability of productive uses of capital to keep pace with money supply and speculative appetite seems a more likely rationale for current asset valuations than investors having capitalised a more predictable distant future.

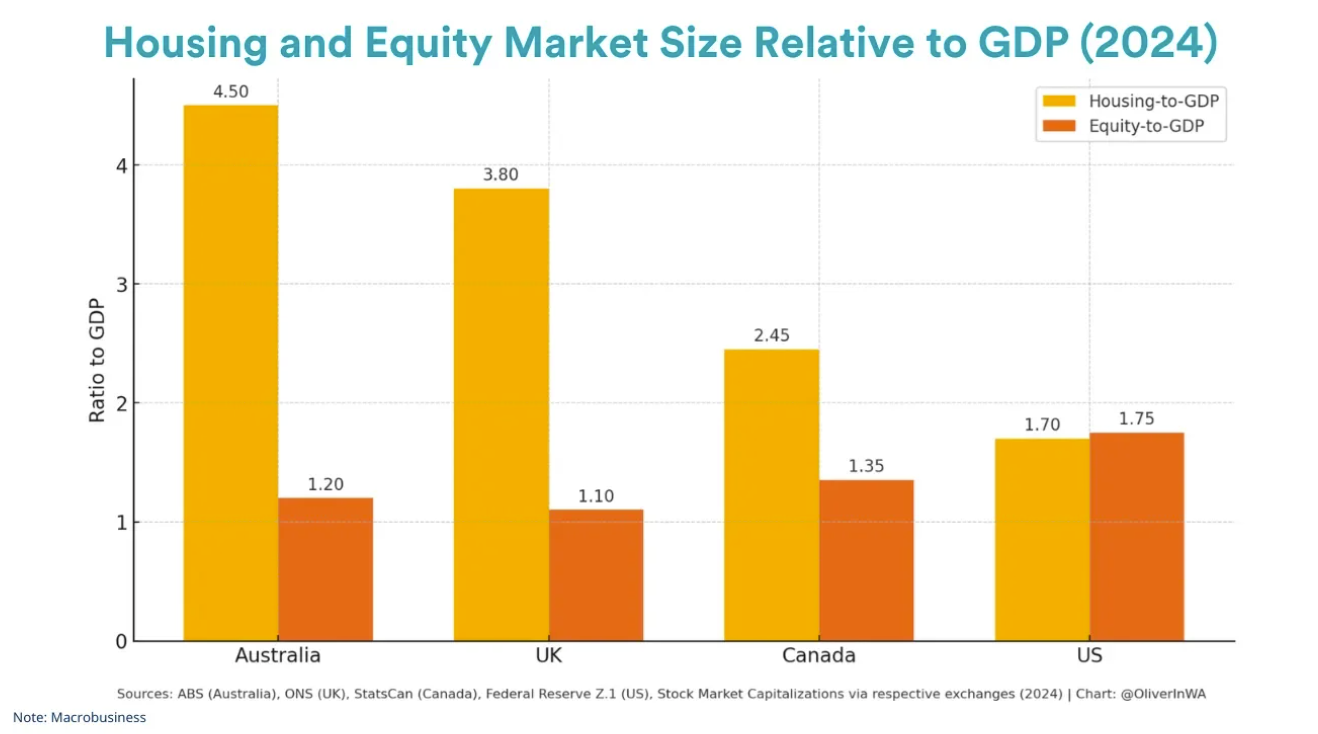

Asking AI the question of whether a sustainable economy can be built on property prices 4 times the GDP of a country provided an unequivocal response. “No, a sustainable economy cannot be built on house prices that are four times the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While house prices and GDP are correlated, excessively high house prices create affordability problems, distort resource allocation, and ultimately hinder long-term economic growth”.

The lens through which we have always sought to value companies is one of economic value creation. The principle is a fairly simple one. A business which delivers long run returns on book value which are largely in line with those investors expect, should trade around book value. Businesses which can sustainably do better than this should command a premium to book value, and those which can’t quite manage it should trade at a discount.

The laws of economics suggest that new competitors will always be looking to enter a market in which these excess returns are available, so sustaining these returns for any length of time isn’t supposed to be easy. It is why we are cautious in extrapolating high returns into perpetuity and why we believe extremely high multiples of earnings and book value should be the exception (rather than the norm which they have become today).

Whether using return on invested capital (ROIC) to determine the returns available to apportion between debt and equity providers or return on equity (ROE) on the contribution of equity holders alone, the maths are similar. Aggressive return targets, write-downs, accounting tricks and ‘adjusted’ numbers aim to convince investors history is better than it seems and the future will be even better. Investors earn the future returns which will remain grounded in reality and driven by competition.

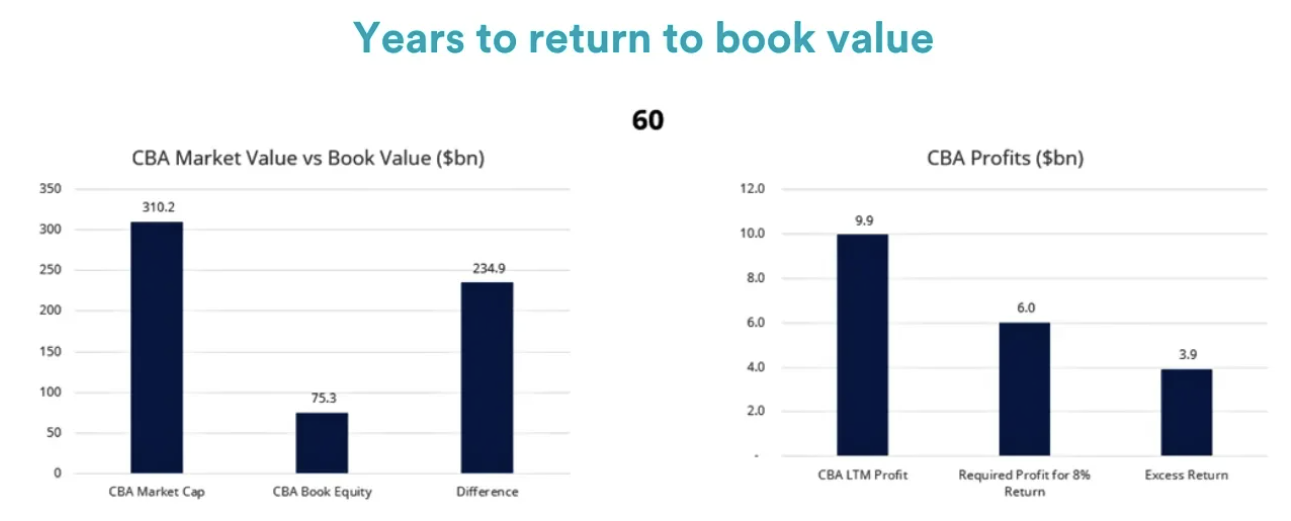

As index investors continue to direct about 12 cents in every dollar of Australia equity investment to CBA (ASX: CBA), it provides a useful example. Assuming we’d happily earn equity returns of about 8% from an investment in the Australian banking sector, if we could buy the business at book value and these returns proved durable in perpetuity, we’d be walking on sunshine.

CBA, through a combination of scale advantages (mainly millions of depositors inclined or compelled to provide CBA with cheaper funding) and good management, manages to earn returns above this level. It is the best bank in Australia by a fairly wide margin.

On the most recent book value of $75bn our 8% ROE target would only require profits of $6bn. CBA managed $10bn (ROE of about 13%). This excess return of $4bn is the fuel for paying above book value for the company.

Assuming the company doesn’t grow that much (probably a fair assumption for a country carrying more mortgage debt than just about anyone in the world), but we assume this ROE is sustainable, we can impute this extra value in paying a price above book value for each year of excess return we assume for CBA.

Unfortunately, the current excess over book value is in the vicinity of $235bn ($310bn market value less the $75bn book value). Assuming CBA stays really well run, stratospheric house prices don’t go down and the economy doesn’t have any of those pesky bad debts which have been known to throw a spanner in the works for bank investors historically, the $4bn or so in annual excess only needs to last until the year 2085 for a CBA investor to receive their average 8% annual return.

Looking at it another way, should this excess not prove sustainable and entirely unforeseen events such as competition, government intervention/excess taxes or bad debts send these returns back towards the 8% level, and market pricing sought to incorporate this new normal into valuation, the CBA price would need to fall about 75%.

‘Risk of Ruin’, a podcast to which I listen occasionally, discusses risk taking and payoffs in various investing and gambling pursuits. Taking sensible risk adjusted bets seems to us to be an essential part of our value proposition to clients.

As YFYS (Your Future Your Super) encourages our industry to behave like lemmings and conceive ‘risk’ as not having 12% of an equity portfolio in CBA, inducing incremental buying in CBA (along with passive buying) from fund managers seeking to ‘reduce risk’ by reducing underweight positions as valuation moves inexorably higher, it is tough to align this behaviour with any form of sensible risk control.

As you might conclude from the above discussion our assessment of the fundamental value and risk payoff in CBA, we would rather pull out our fingernails than to be forced to buy more CBA at current prices, however, as we reach limits in pre-ordained portfolio rules, we may be required to do just that. In our view, we are exposing investors to almost certain loss, probably not the prerequisite for wanting it to be the largest position in your portfolio. If this is progress, we’re struggling to embrace it.

It is crazy to suggest CBA is the only listed company suffering from valuation distortion. The 4 times book value accorded to CBA makes it look like a deep value stock versus a significant proportion of the market. The love affair with businesses employing minimal capital given the ability to create economic value quickly relative to a small base is currently seen as having no trade-off with business duration.

Assuming returns on capital of 40-50% are sustained in perpetuity across a broad range of businesses is a terrific way to justify the high valuations accompanying any business with a smell of future revenue growth potential and an untapped TAM. It does not have much grounding in economic reality or historic experience.

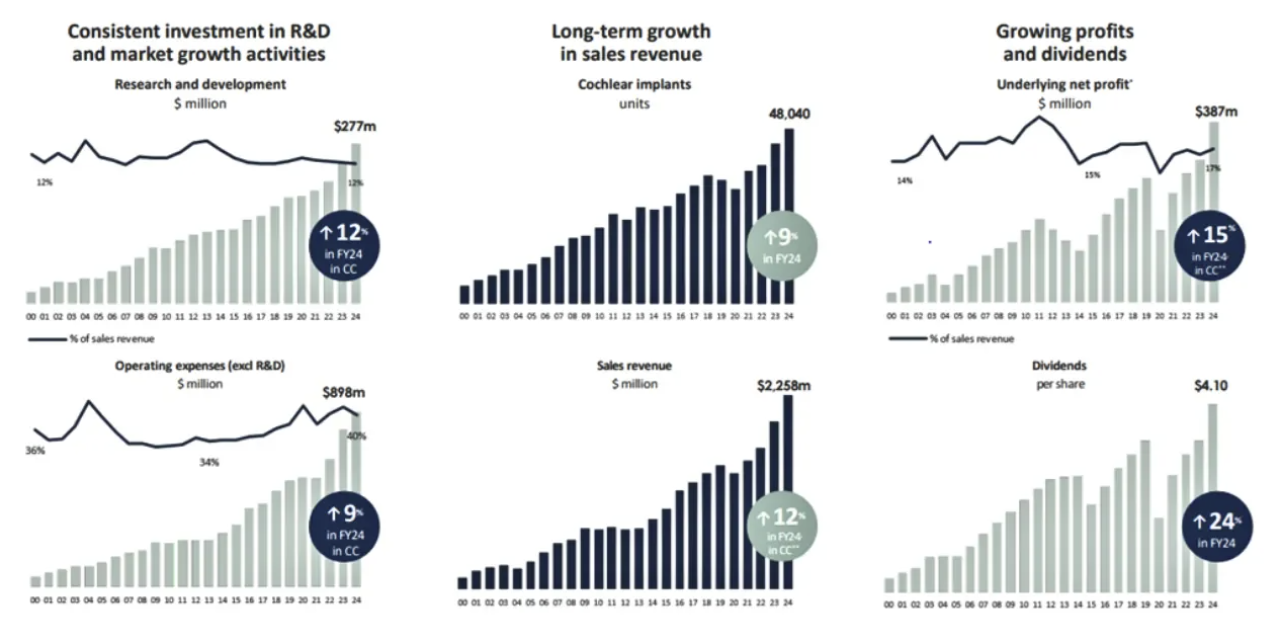

The difference between the $200m of book equity and the $30bn in equity market value (150 times book value) for Pro Medicus (ASX: PME) or the $1.8bn book value in Cochlear (ASX: COH) versus its $20bn in market value (11 times book value) must all be bridged with economic value creation in the future.

Companies have become adept at ensuring all bad news from the present is sandwiched with optimism for the future. Cochlear downgraded net profit expectations a little in June, to around $400m alongside the release of detail on their new implant system. The share price ended the month considerably higher as enthusiasm for the future won the day. Cochlear has been an amazing company for many years as the charts below illustrate (alongside some of cleanest accounting), even though that history is only 30 years. There are few better in Australia. Whilst we love to own companies of its quality, the investment maths are extremely challenging. Future economic value creation implied in paying $18bn above book value is many multiples of that created in Cochlear’s entire history. Pro Medicus and many others make Cochlear look like a deep value opportunity.

The infatuation with revenue growth and momentum invariably leave opportunities in the more mundane, and now is no exception. Energy and materials stocks have been broadly shunned (with the exception of gold). The takeover approach for Santos by the ADNOC (Abu Dhabi National Oil Company) led consortium suggests some are prepared to diverge from the crowd.

As a Santos shareholder, we’d acknowledge the common sense behind the bid. Pitched at a level that is somewhere near where we’d value the company using less than extravagant oil/gas price assumptions (the main variables which matter in any resource company valuation), at a time where the share price has languished despite a focus on delivering strong cash generation and cost control, the decision isn’t a no-brainer. What the government decides on foreign ownership grounds will be a lottery. Listed companies are owned by disparate shareholders in varying geographies and domicile is increasingly irrelevant. The power to ensure gas is delivered to domestic customers and tax is paid on earnings is probably of greater importance.

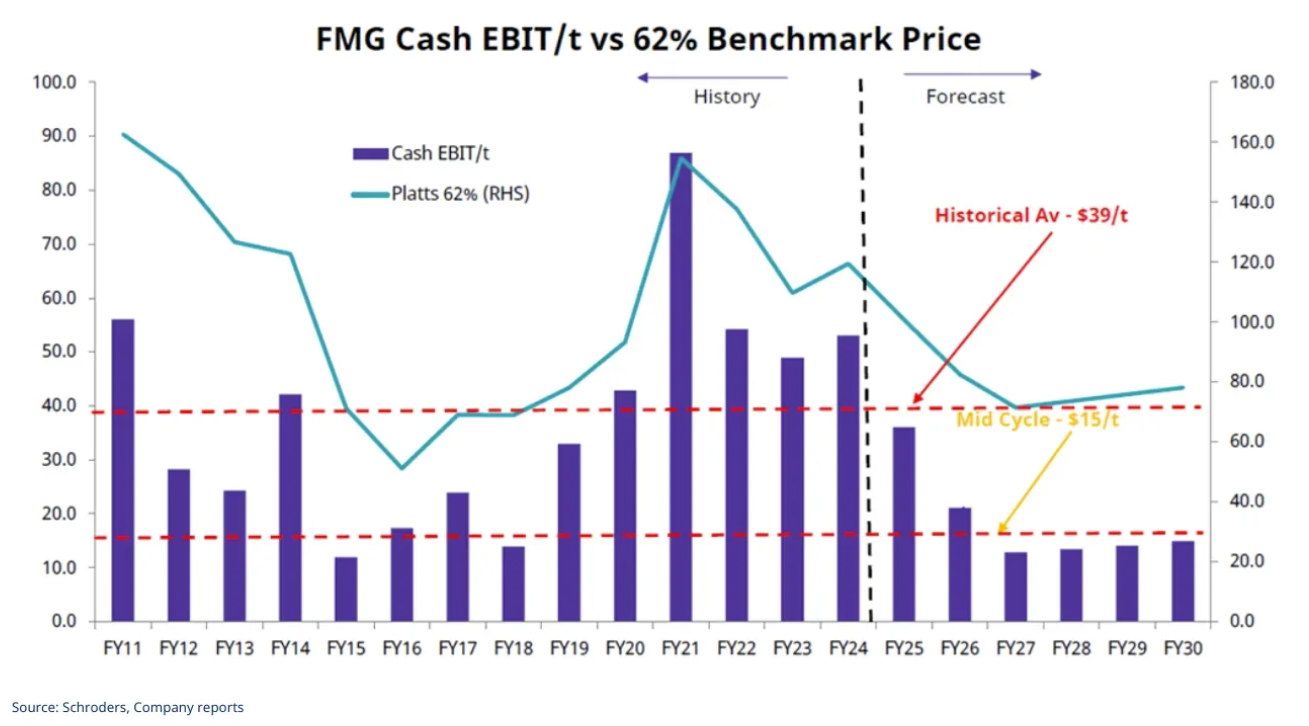

Sensible investment opportunities where one does not need to be an unbridled optimist on future economic value creation remain fairly abundant in materials businesses. We have not owned Fortescue for basically all of its history. It has created large amounts of economic value.

The total value of the business (equity plus debt of US$2bn) is around $US30bn. The book value of equity is nearly US$20bn (around1.5x book value). It is producing in the vicinity of 190m tonnes of iron ore annually.

While the infrastructure and assets supporting the business were built for somewhere near US$100/tonne of capacity, we’d estimate doing the same job today would be double the cost, meaning somewhere near US$40bn. This number is relevant, as it is almost always ignored by the proponents for higher levels of resource taxation. When existing projects deliver only moderate returns on historic cost and would deliver unacceptable returns at current replacement cost, they will not get built. Increase the tax and they certainly won’t get built. The range of operating profit it has earned on each tonne produced has varied between about US$10 and more than U$80 through it’s history.

Our assumptions for a well-supplied iron ore market in the future and a challenging time for higher cost players, means we anticipate operating profits of around US$15/tonne (less than half current levels), a little under US$3bn on our 190m tonnes. Going back to our economic value principles, assuming we need a return on capital of somewhere near 10% on our capital base of about US$22bn, the business is still delivering US$600-$700m of economic value at these iron ore prices and far more at current prices.

Value creation seems highly likely to bridge the gap between market and book value inside 10 years and the business should remain durable well beyond this time frame, particularly given significant investments in decarbonisation (discussing the progress of the battery operated truck fleet and viewing the control room with the CEO on a recent visit left us extremely impressed). This is comfortable country for old men.

While touching on the risks to businesses of all types as governments seek to plug the ever larger hole between government spending and tax revenue, we would suggest the first ports of call should be companies enjoying excessive profitability. Recent evidence would suggest far lower levels of sophistication in the government’s plan. While happily handing billions to Qantas and not asking for it back and watching the tobacco excise disappear into the hands of organised crime, industries where the government is trying to make life difficult are at the other end of the spectrum.

As Chris Bowen suggests the default market offer is providing too much profit for energy retailers, one could observe that the total annual profit per customer earned by energy retailers is somewhere in the vicinity of $100 per customer. Suggesting energy bills are rising because of excessive retailer profitability is unadulterated garbage. If you cut retailer margins by 25%, not only will a bunch of smaller retailers probably go out the back door, you will be able to return a grand total of about $20 a year to customers.

The cost of living relief will be overwhelming. Similarly, as Mark Butler threatens pathology operators with a price fixing probe, one might observe a profit profile which has collapsed in the past decade, offers margins in the single digits and the second largest player in the industry has a market value of about $500m. Votes, rather than economic reality, seem to be the driver of government behaviour. Like Sheriff Bell, it would be nice to see a few decisions guided by doing the right thing rather than expedience and votes.

Contributors and Detractors

Contributors

BHP Group (ASX: BHP) (Underweight) (-3.8%)

While incremental supply from Rio Tinto’s Simandou project sits on the horizon in a steel market which is already struggling to digest surplus Chinese production, caution on the iron ore price outlook is understandable, albeit yet to translate to lower iron ore prices. At around 2.4 times book value for a privileged and low operating cost asset base, continued underperformance has eroded much of the over valuation we perceived, given the business still has solid long-term prospects and good exposures to metals such as copper with extremely positive long-term appeal.

CSL (ASX: CSL) (Underweight) (-3.9%)

Recent years have seen an interruption in the growth path for CSL as the strong volume growth and reliable price increases that have driven the plasma fractionation business were complicated a little by COVID and the overpriced acquisition of Vifor. The high drug prices that have underwritten strong returns for most pharmaceutical companies are also under the microscope to a greater degree as governments seek to suppress the alarming trajectory of spending driven by ageing populations. We continue to believe the CSL business is a strong one, which should continue to deliver solid returns and while the pricing of these prospects is now far more realistic, pricing will remain a vastly more important driver of earnings prospects than volume.

Metcash (ASX: MTS) (Overweight) (+23.7%)

Despite a diversified business exposure across supermarket and liquor wholesaling and hardware and a solid track record of working hard to deliver reasonable earnings growth in fairly mature businesses (also challenged by the disappearance of tobacco from legitimate retail channels), Metcash has traded at a wide discount to larger supermarket peers Coles and Woolworths. A passionate management team determined to change the perception of independent retailers as necessary losers in the market share battle with majors leave us positive on the outlook for a business with longevity and valuation appeal.

Detractors

Commonwealth Bank (ASX: CBA) (Underweight) (+22.4%)

Discussed at length above, it is the valuation of the business which dictates portfolio positioning. A highly competent management team, excellent franchise and strong technology are undoubted positives. A $235bn premium to book value is a big negative.

South 32 (ASX: S32) (Overweight) (-9.6%)

Like most materials stocks outside the gold sector, South 32’s assets across alumina and aluminium, copper and manganese have not captured the imagination of investors seeking minimal capital investment and maximum revenue growth. We continue to believe the suite of assets are solid, well-managed and significantly undervalued.

Fletcher Building (ASX: FBU) (Overweight) (-9.4%)

While signs of emerging from many years in the wilderness of mismanagement, accounting trickery and cost bloat are positive, challenging construction market conditions in New Zealand and drawn-out losses from construction projects with unfathomably poor risk control have weighed on recovery prospects. While the prize from improving operating disciplines and simplification are material, the journey has been painful.

Market Outlook

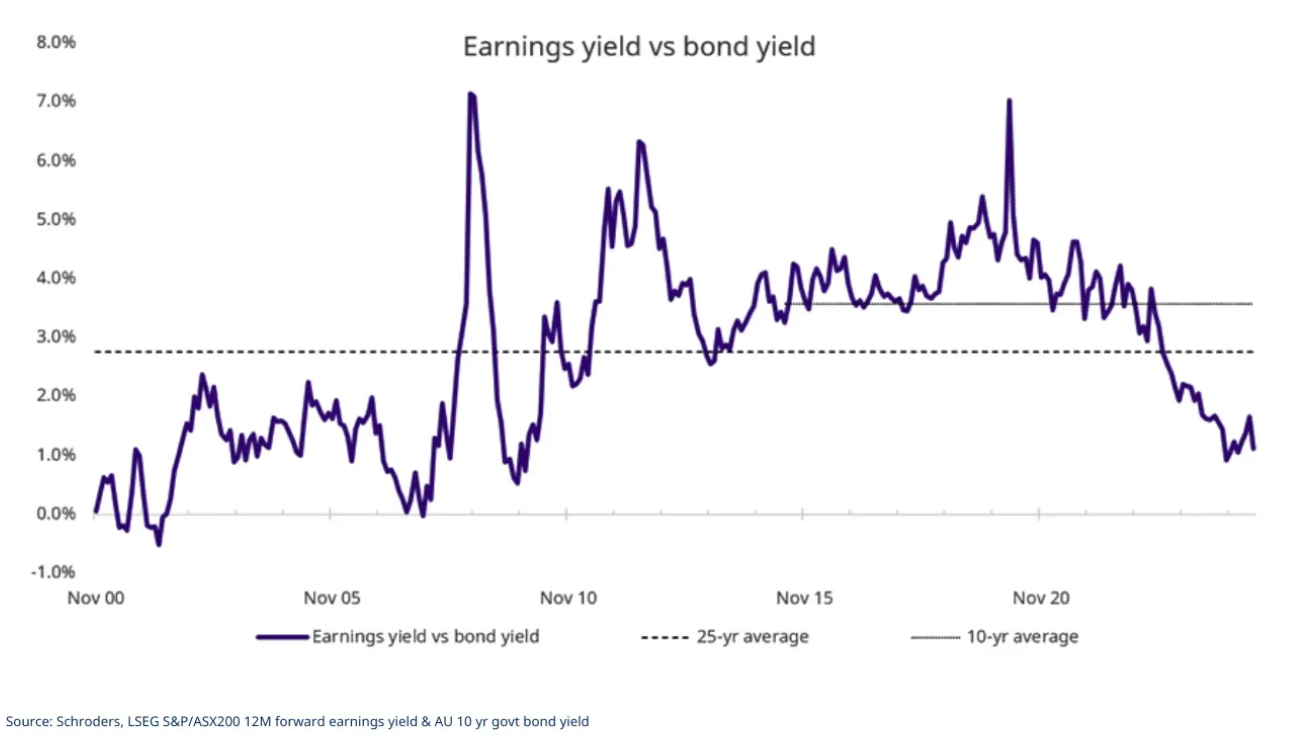

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the realisation governments have little intention of ever matching spending with tax revenues is causing a few ructions in bond markets. Equity markets have been a beneficiary largely due to their size and liquidity. The gap between earnings yields and bond yields has moved into fairly dangerous territory, albeit partly driven by the return of bond yields to more normal territory. Highly leveraged and low productivity growth western economies are hoping lower interest rates can spur something other than a little more speculative activity. Domestically, the lack of capacity in jobs which might provide an outlet for more productive spending in new housing and infrastructure makes it difficult to believe lower interest rates would spur anything other than already high asset prices.

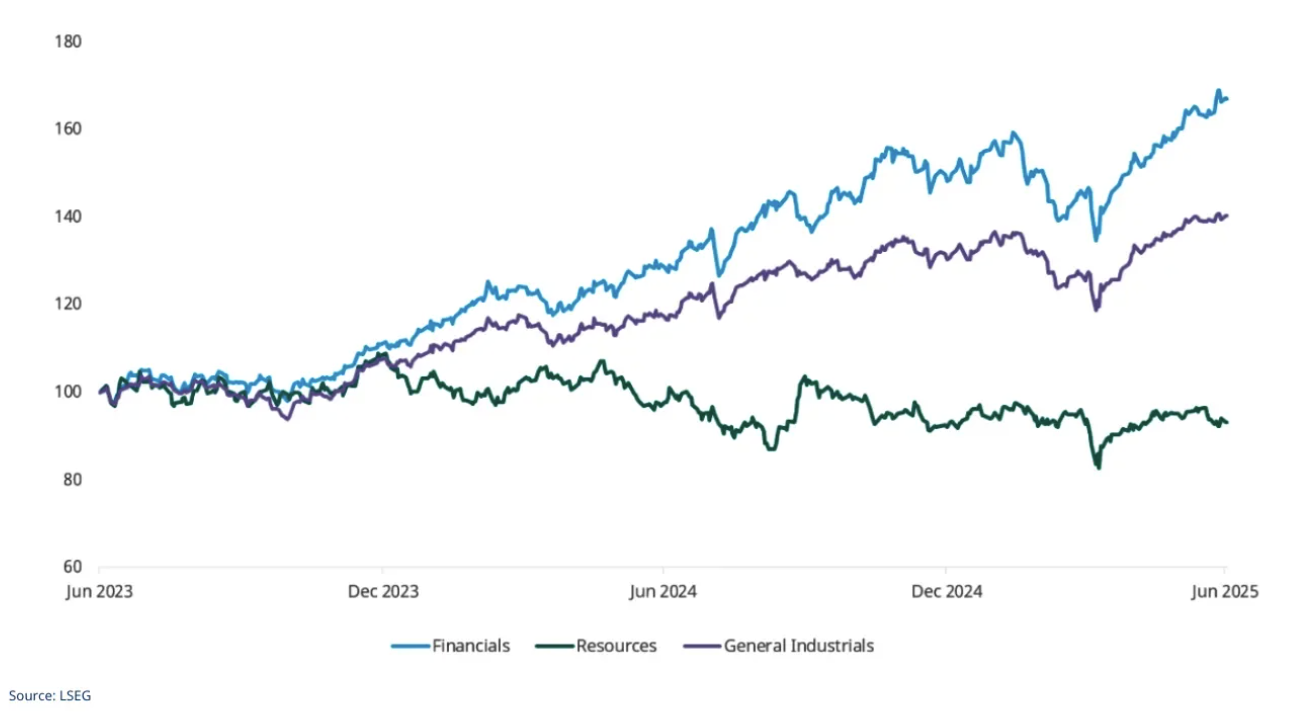

As asset markets continue to grow in size at rates faster than underlying economies, it is understandable how powerful asset prices have become in driving behaviour, both in investing and consumption. Financials and technology stocks in the equity market have trounced real economy counterparts in recent years. Feeling wealthier as asset values outpace wage growth and drawing down untaxed money by refinancing against the rising value of a home are features of the modern economy, albeit continuing to drive a wedge between asset owners and the rest. The tail is most certainly wagging the dog when it comes to asset prices versus the cashflows which must invariably support them in the longer run. Chasing and predicting human behaviour has become a feature of equity market investing as cashflows and economic value fade in importance. Cavernous gaps have grown between the book value and cashflows supporting out of favour elements of the equity market and those driven by the crazy price to book ratios and fanciful long-term forecasts which allow rampant speculation to masquerade as investment. Holding on to traditional measures of investment appeal and the slow work of genuine value creation is hardest when equity markets provide regular and large rewards from fast money. As Llewelyn Moss found, grabbing the bag of apparently free money often has a heavy long-term cost.

Learn more about investing in Schroders' Australian Equities.

8 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned