“Down goes the dollar”: Morgan Stanley on rates, tariffs and the new macro

Macroeconomics is a story of cycles, but each cycle has its own tale to tell.

With rates coming down around the world and inflation easing, conventional wisdom would suggest growth could be on the horizon.

As is always the case, it’s slightly more complicated than that.

The macro situation could make it a good time to invest outside the US, according to Matt Hornbach, Morgan Stanley Head of Global Macro Strategy.

“We have the dollar in our outlook depreciating another 9% on the DXY basis, which of course is going to be primarily driven by the Euro and Yen," said Hornbach.

"But the depreciation that we have in the dollar is largely a story of the US slowing in economic activity.”

While he sees it difficult for the Federal Reserve to lower rates right now, he believes the impact of tariffs will eventually slow US economic activity enough to see the Fed lower its policy rate by 200 basis points next year, 100 basis points below what the markets are currently pricing in.

“Our vision for the dollar is primarily its cyclical story. The US is slowing, the Fed has waited to get past the hump of inflation and has to ultimately adjust the policy rate lower, and down goes the dollar.”

He sees US 10-year Treasury bonds at 4% by the end of 2025, and lower again by the end of 2026.

It means global investors may reconsider not only their exposure to the US dollar, but whether US dollar-denominated assets could be better invested elsewhere.

“Investors are taking a second or third or fourth look at the long end of sovereign markets or credit markets outside of the United States,” said Hornbach.

Tariff tactics

Ariana Salvatore, US Public Policy Strategist at Morgan Stanley, says tariffs are likely here to stay.

The key for investors is thinking further ahead than next week’s latest twist in the trade war.

“At the end of the day, we think that the Trump administration wants to keep this 10% baseline on most of our trading partners,” Salvatore said. “Part of the reason is because it's a really important revenue source - it could potentially be used to offset the cost of the tax cut extension.”

But China will still be hit with its 30% tariff rate in Morgan Stanley’s base case.

“We still think the administration finds it important to have a higher rate on China than the rest of the world because it fits this derisking narrative.”

But there’s a crucial detail missing in much of the coverage of tariffs.

“The important point about Trump's tariff policy is to zoom out and think about the purpose driving it,” says Salvatore.

Trump is committed to a policy of industrial reshoring and deglobalisation, an approach shared by both Democrats and Republicans.

It’s why she sees tariffs around Section 232 products like steel and automotives (and likely semiconductors and pharmaceuticals) sticking around, due to their importance to US national security.

The Biden administration had itself implemented the CHIPs Act and other legislation to achieve similar ends. The main difference was in the approach.

Biden’s strategy was “more on the carrot side rather than the stick side,” says Salvatore. “It's just a very different approach to solving the same problem.”

But there’s also a sense of urgency given the US government’s debt ceiling deadline, which is expected around August or September.

Trump’s “big beautiful” tax bill should pass the US senate, with some changes, but is a spectre lurking behind ongoing trade talks.

“Our trading partners have calculated that really more of the pressure is on the US,” says Salvatore. “[They’re] less incentivised to come to the table and to offer anything.”

She sees potential opportunities for the US government to settle for narrower concessions from trading partners, which would resolve the tariff standoff more quickly.

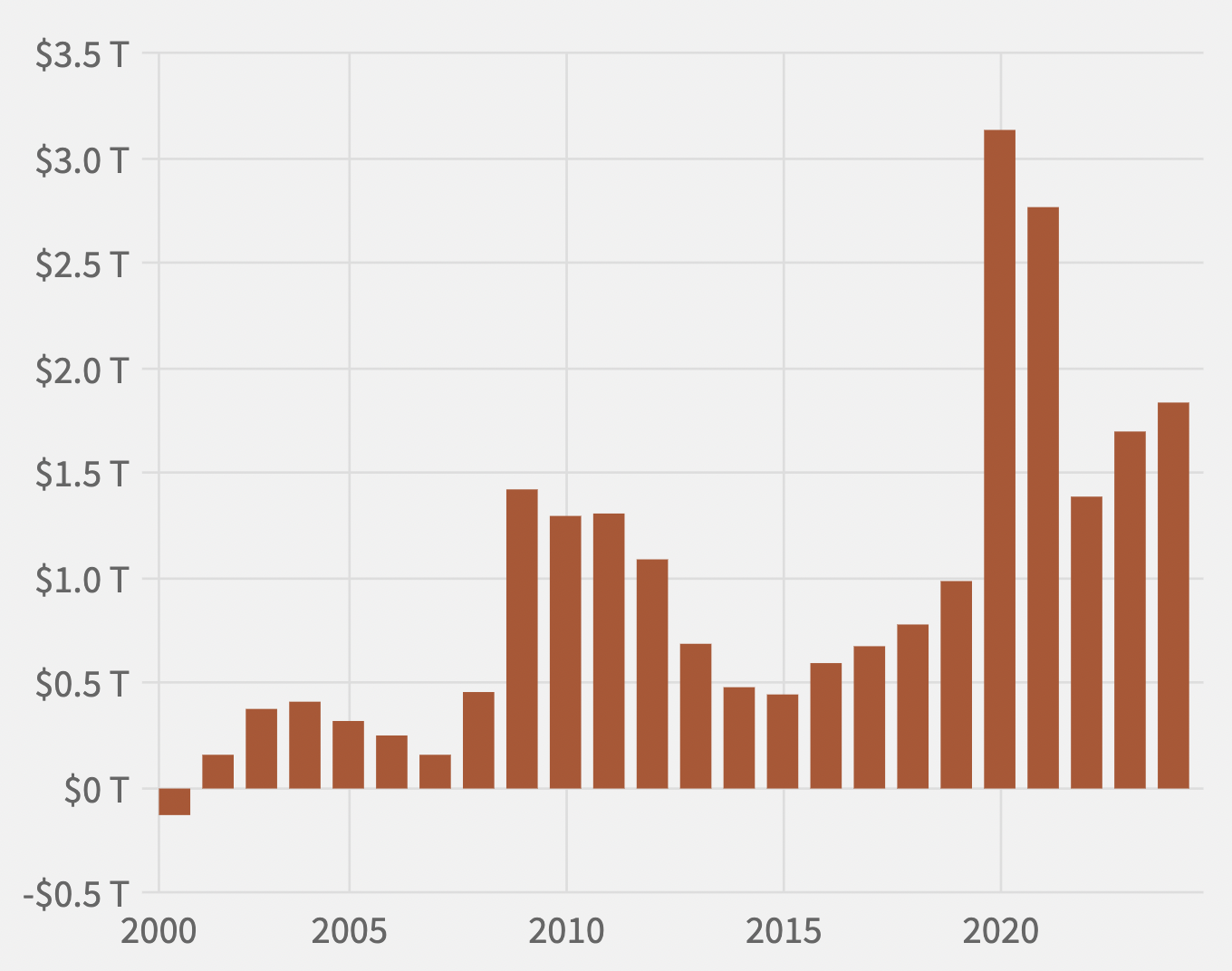

Trump’s bill is projected to add US$2.5 trillion to the US deficit over 10 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Yet CBO analysis also suggested tariff revenue could counteract that deficit over the same period, says Hornbach, were they to stay in place.

But he also has a word of caution.

“When you look at markets today, they might have you believing that tariffs don't really matter all that much,” said Hornbach.

The big surprise for investors, says Hornbach, may be how much tariffs do end up impacting economic activity, even if prices don’t change that much.

Salvatore agrees, and says macro variables - rising government interest costs, mandatory spending programs and weaker revenues - will already be driving an additional US$220 billion deficit.

That means a much weaker growth outlook for the US.

The local impact

Chris Read, Australian economist at Morgan Stanley says Australia is well-positioned to handle any changes to the trade landscape.

“Australia will be relatively resilient, particularly when it comes to some of these trade policy adjustments,” said Read.

It also sets the stage for a more dovish RBA and supports Morgan Stanley’s view that Australia will get two more moderate rate cuts this year.

“What is inflationary for the US is expected to be somewhat disinflationary for other countries,” said Read.

It also means the Albanese government can pursue a growth outlook.

“A key benefit for Australia is that relative to the US and some other economies, our government can expand and support economic growth,” said Read.

“Fiscal policy has been a really important growth driver and I think post-election, with a majority government, we expect that to continue. The key difference this time versus last term is that you'll see greater focus on revenue.”

Learn more

Information is everywhere; true insight is rare. Morgan Stanley brings knowledge and experience from across the globe to make sense of the issues that matter. Find more insights here.

5 topics