Financial economy & real economy

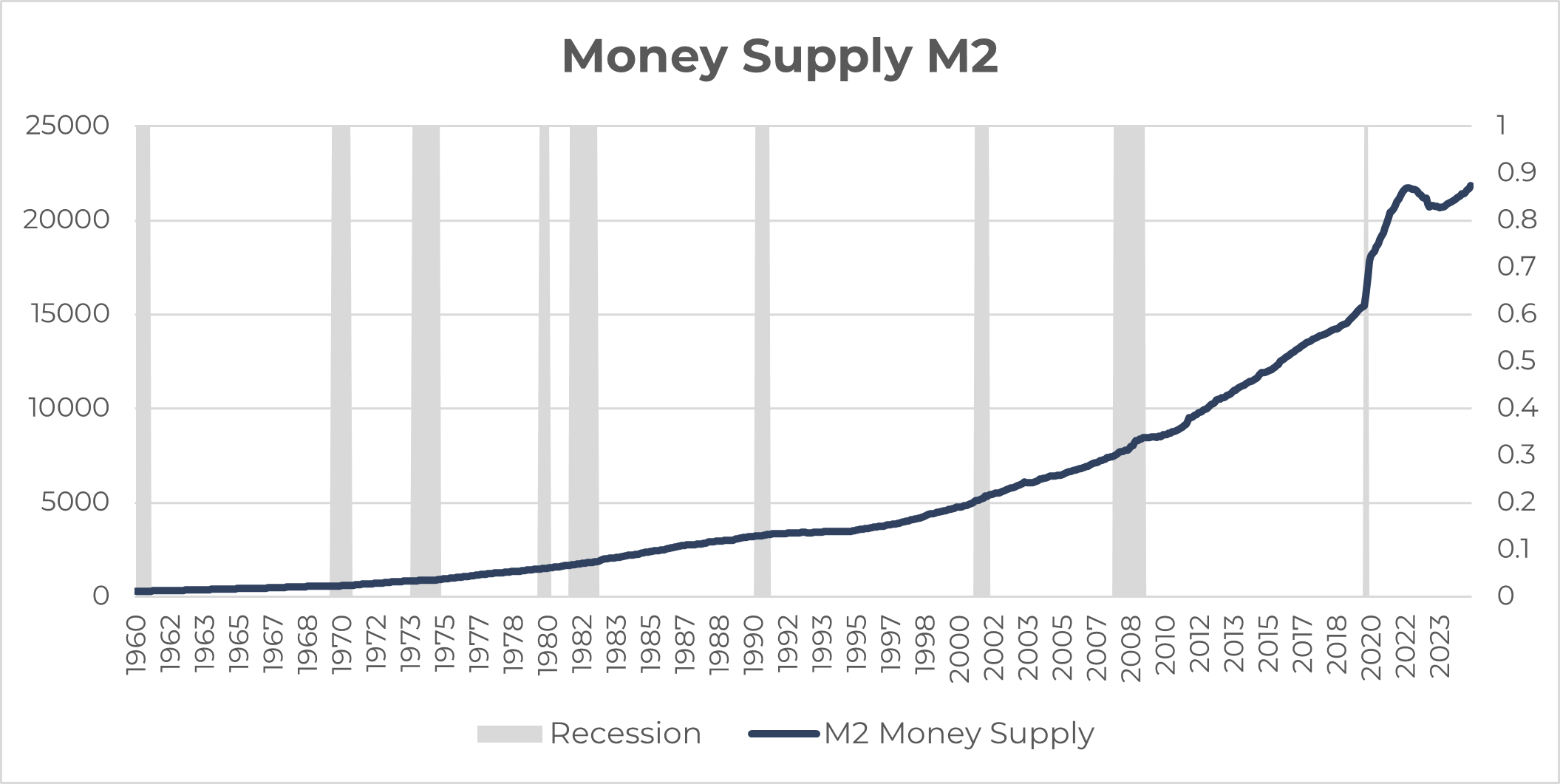

Yes, financial markets and the real economy are not the same, but that relationship is not constant over time. If participants in the real economy did not exhibit wealth inequality, these two could be quite independent which was what we were closer to pre-GFC. However, the past ~15 years it has been clear that the wealth inequality has grown via bailouts of private institutions and immense money printing, asymmetrically growing the wealth of the rich and hurting the lower-income earners:

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

If wealth inequality has become materially larger in the US, then we should expect a changing relationship between the real economy and markets. Why?

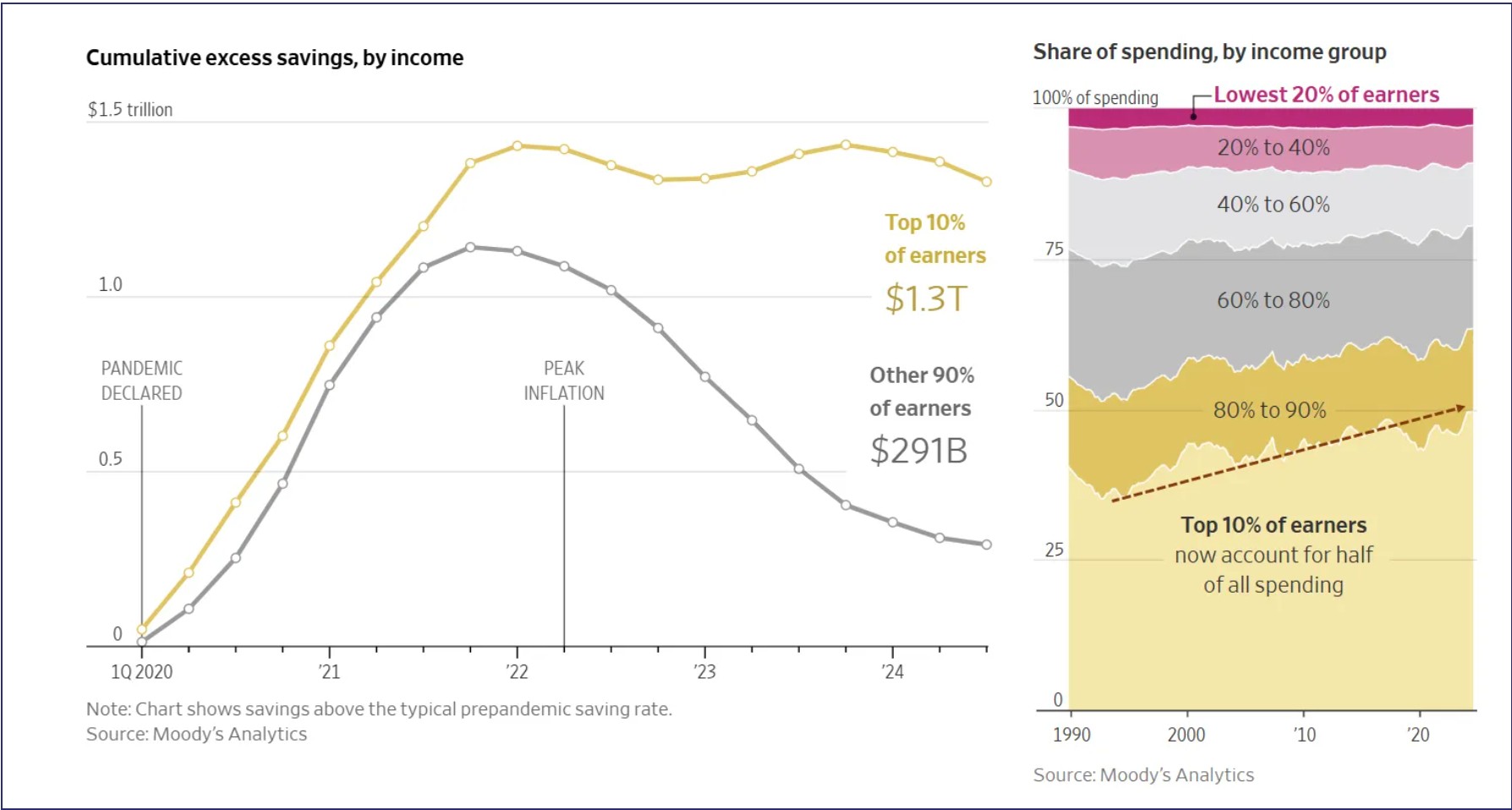

50% of consumption in the United States is driven by the top 10% of population (richest, most asset-wealthy individuals), up from ~30% in 1995.

A significant pullback in financial and asset markets, where the wealthiest primarily store and grow their wealth, can trigger a negative wealth effect and a confidence crunch. This would materially hurt consumption within the US economy. While not equating the real economy with the financial economy, this highlights a time-varying relationship where the real economy is increasingly sensitive to the spending patterns of the wealthiest.

2025 Example

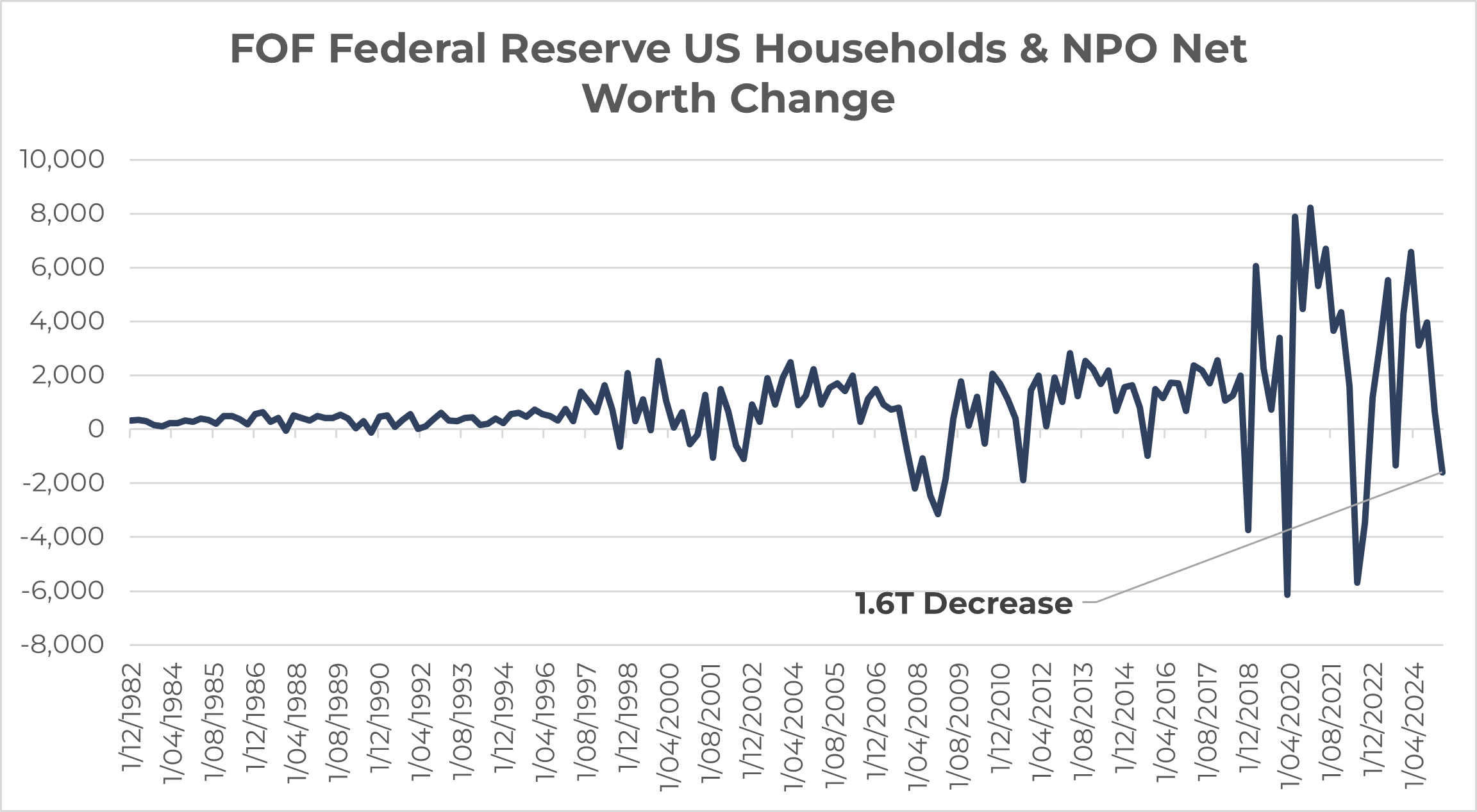

Take Q1 2025 as an example where US household net worths sunk by -$1.6 trillion, the largest decrease since 2022. The large loss in the value of equity holdings (-$2.3 trillion) was the greater driver of this. That’s quite a significant blow to the wealth of these top decile earners, which may in turn lead to less spending, and hence lower GDP.

In the United States, approximately 70% of household wealth is tied up in the equity markets. As a result, equity market volatility may significantly affect consumption patterns.

A similar dynamic has played out in China, though centred around real estate: around 60–70% of household wealth was concentrated in property. Following widespread bankruptcies, consumer confidence collapsed, spending stalled, and savings rates rose. However, unlike the U.S., consumption comprises only 35–40% of China’s GDP.

What about Bond Markets?

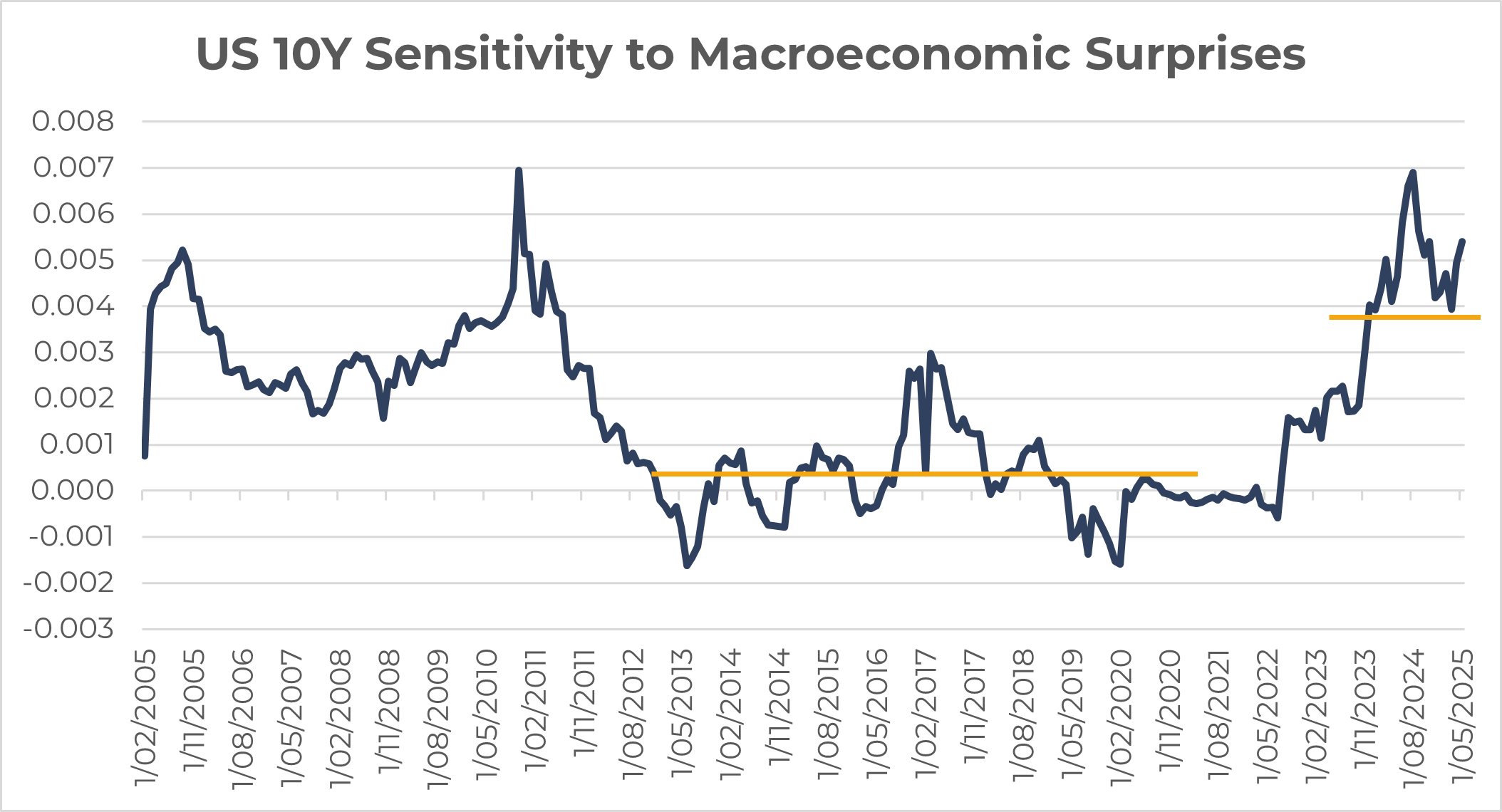

As illustrated in the chart below, we know that markets now are inherently more sensitive to macroeconomic volatility and surprises, which is also a link between the real economy and the financial economy.

So, in this regime, the 2 most popular asset classes are clearly more sensitive to macroeconomics, or in another words, the real economy.

Well, wouldn’t a market selloff lead to less demand for goods and services and therefore lower inflation?

Unfortunately, given the tariffs that are in place, import costs will be higher (US manufacturers must pay tax to US government to buy exports from rest of world), and hence this can cause upward pressure on prices.

This creates a significant dilemma for the Federal Reserve. Ideally, the Fed would lower interest rates to stimulate a stagnating economy, but elevated prices limit their ability to do so without exacerbating inflation. Compounding this issue, the U.S. government must finance growing budget deficits and continue to raise the debt ceiling—a process increasingly scrutinized by markets, as evidenced by rising term premiums and signs of foreign divestment and waning trust. The Fed is caught in this stagflation-lite type environment and historically we’ve seen rampant government spending make the Fed not act as independently as it would’ve liked to.

Summary

In today’s financialised economy, the market is not the economy, but the market increasingly shapes the economy.

The post-GFC era has bred a fragile equilibrium—where asset markets prop up consumption and consumption props up GDP. As inequality grows, the line between Wall Street and Main Street becomes more of a feedback loop than a dividing wall.

4 topics