How long can the good times last? A data-driven reality check for investors

Investing success is intoxicating. Logging in to discover a new all-time high in your account balance floods your brain with feel-good chemicals and reassurance that you’re ‘doing it right’.

But let’s be honest - it has been easy to make money lately. Everything has been going up – equities, gold, crypto. Bonds have been paying decent yields, and private equity and credit have been delivering solid returns, despite the spectre hanging over them. Aside from a few pockets - like emerging markets, some commodities and some property - it has been a goldilocks period for investment returns.

It is because of this ease with which money has been made that the feeling that you are ‘doing it right’ is quickly followed by a commensurate feeling of ‘surely this can’t last’. It’s classic loss aversion – the psychological tendency for us to feel the pain of losses (even potential losses) more intensely than the pleasure of equivalent gains.

It is also why, amid any bullish run in markets, articles with headlines like the ones below will be so popular;

- America’s top banker sounds warning on US stockmarket fall

- Bank of England warns of AI stockmarket bubble

- A major stockmarket storm is about to be unleashed

- Investors are fretting that the stockmarket rally is on borrowed time

The cure for market anxiety? Data, not drama

So, what are we to do when we get all up in our feelings about our investments? Unleash your inner nerd and go back to the data. As boring as that sounds, it’s really all that is worth doing. It's also all you can do.

Forget trying to predict when market sentiment might turn, that’s a mug’s game. If anything, you will most likely sell too early and miss a good part of the rally. What you can do, however, is have a plan for when the underlying drivers of markets – things that are observable and quantifiable - change.

What data should you look at?

For all the noise – and there is a lot of it right now - at a macro level, investment returns are driven by three factors;

- Economic growth

- Inflation

- Interest rates

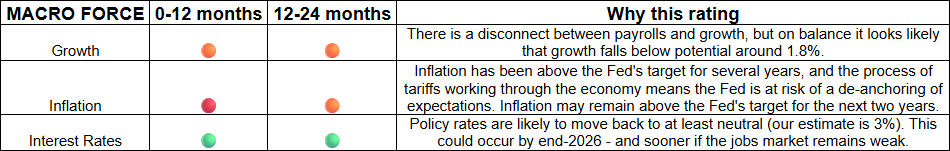

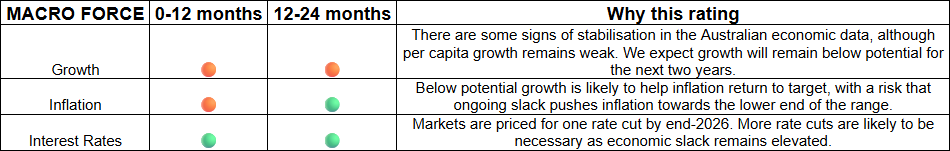

To make sense of these factors, you can use a traffic light system - green for supportive, amber for neutral or uncertain, and red for risky - to rate whether these factors are likely to provide headwinds or tailwinds over the next 12-24 months. The good thing about these factors is that the RBA and Federal Reserve, along with a host of economists and research houses, provide forward guidance for them - most of which are readily accessible to those willing to look.

For the purposes of this wire, I reached out to the person who taught me this system, Isaac Poole, Chief Investment Officer at Ascalon Capital, for his current assessment of where things are at.

US

Australia

Key takeaways

Please note, the key takeaways were also provided by Dr Isaac Poole

- Growth: Amber in both economies - resilient but moderating. Growth seems likely to fall below potential over the next two years.

- Inflation: Red in the US – the key risk here is that five or more years of inflation above target starts to increase the chance that expectations are de-anchored from the 2% target. Amber to green in Australia, where economic slack could push inflation back towards the lower half of the target range.

- Interest rates: Green as both the Fed and RBA are likely to ease policy. The pace and magnitude of the cuts are extremely important for investors.

- Risk skew: Red. The key risks here are in central bank and market expectations versus potential outcomes. Markets and the central banks have a very benign, Goldilocks narrative. But sticky inflation and slower growth are themselves a risk. And while rates are likely to be cut, the reason for cutting matters. A gradual reduction can help support growth, but more extensive emergency rate cuts would signify something much worse for the economy.

What about liquidity?

Liquidity is the oxygen of financial markets. Its abundance inflates valuations, whilst its sudden absence suffocates them. While earnings, valuations, and sentiment matter, liquidity shocks are the accelerant that transforms stress into crisis.

In 1929, tight Fed policy and a credit contraction fuelled the Great Depression. 1987’s Black Monday saw portfolio insurance selling overwhelm limited liquidity. 1998’s Long-term Capital Management Crisis saw a leverage unwind and evaporating liquidity in bond markets, whilst we all know what happened in 2008 during the GFC – interbank lending and mortgage funding markets seized up entirely.

Right now, there are no signs of an imminent liquidity withdrawal. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. There is oodles of liquidity sloshing around the financial system, looking for a home to park and generate returns.

At the recent Livewire Live event, Macquarie's Viktor Shvets spoke about the ‘cloud of finance’, i.e. the value of financial instruments that exist in the world, the value of which is now “unparalleled in human history” according to Shvets.

“Today, depending how you count the numbers, the value of financial instruments are at least 5 times, one could argue 10 times, larger than the real economy”, said Shvets.

He went on to point out that in the 1970s, under the Fed guidance of Paul Vockler, the relationship was around 1 to 1, under Greenspan (1987-2006) the relationship was around 2:1. Under Bernanke (2006-2014) the relationship was around 3:1.

Are risks building? Sure. US debt is a ticking time bomb but an explosion is not imminent. Rates are expected to come down, tax cuts are coming in the US, and there remains an abundance of liquidity… for now.

Valuations and the AI question

There is a lot of commentary at the moment about the potential for spending on artificial intelligence to be ground zero for the next stockmarket collapse. Much of the liquidity and capital mentioned above is finding its way into AI-related assets, stoking fears of a bubble. But what about the earnings?

To be fair, the current landscape of AI-related corporate earnings tells two different stories – strong fundamental growth and pockets of speculative excess.

On one hand, AI is driving real, tangible growth for many of the world’s largest companies. Cloud giants like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon are seeing acceleration in revenue as customers invest in AI capabilities on their platforms. Semiconductor firms like Nvidia and Broadcom are reporting eye-popping sales increases directly tied to AI chip demand. Even companies like Meta and Palantir – one an ad-platform, the other enterprise software – have rejuvenated their businesses by deploying AI and are delivering better-than-expected earnings as a result.

In these cases, the AI boom appears fundamentally justified. The earnings oomph is matching (or at least catching up to) the stock price optimism.

For example, Nvidia’s earnings have grown so explosively that its valuation, while high, is not outlandish relative to its new income level. Microsoft and Alphabet have P/E ratios elevated versus historical averages, but their AI-fuelled growth and positive guidance lend credibility that higher earnings are on the way to support those valuations. In short, across Big Tech, AI investments are yielding revenue and profit, indicating healthy earnings trends, not just hype.

On the other hand, there are signs of speculative fervour in certain corners of the market. During 2023, anything with an “AI” label attracted investor dollars - at times reminiscent of the dot-com bubble’s indiscriminate enthusiasm. We saw surges in share price far outpacing any immediate financial returns for some companies. Tesla, for instance, added hundreds of billions in market cap largely on hopes that its AI and autonomous tech will pay off eventually, even as current automotive margins shrank.

Many smaller-cap AI plays (from enterprise software firms to chip startups) saw valuations swing wildly without commensurate earnings. Venture capital funding in AI startups hit record highs, and private valuations have soared over the past year (OpenAI was reportedly valued at $80–90 billion in private markets, despite still-formative monetisation). These trends raise bubble questions: Is too much future success being priced in upfront?

Yet, it’s important to note that this AI cycle differs from, say, the 2000 dot-com bubble in one key way:

The dominant players driving the AI trend are highly profitable, cash-generating businesses.

They are pouring those profits into AI R&D and infrastructure at an enormous scale, and still maintaining strong earnings growth. That suggests a degree of sustainability. For example, the combined capex of Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon for AI/datacenters is headed for hundreds of billions in 2025–2026, but each of those firms is growing revenue and profits simultaneously. They are not sacrificing earnings for growth; AI is augmenting both. This does not appear to be a scenario where companies are valued purely on distant hopes with no current cash flow – many AI leaders are thriving in the present.

Of course, like the other factors, there are risks. Poole points out that whilst earnings have been solid, they are slowing - and "the game of lowering earnings guidance to provide easy beats continues".

"If slower economic growth in the US and Australia slows revenue growth, and the margin expansion in the US comes under pressure from higher inflation, then the valuations do start to look challenging.

We don’t think that means you need a correction, but it may mean prices increase by less over the next two years to allow PE ratios to normalise somewhat".

And finally… sentiment

As noted above, this is the great unknown. The market might wake up tomorrow morning and collectively decide that the price being paid for certain assets is too high, and that could be the spark that lights the fire of the next meltdown.

That shift in collective psychology, not data, could be enough to trigger the next correction. But until that moment arrives, it’s unknowable.

The antidote is discipline. I was always taught to trade what I can see, and not what I think – that is, to do whatever I can to remove emotion from the process and instead focus on what can be quantified - earnings, liquidity, and macro trends - rather than trying to outguess crowd psychology.

You might disagree with some or all of the conclusions drawn above, and that’s fine. The goal here isn’t to predict the next move, it’s to provide a framework for thinking clearly amid noise.

For now, the data says the backdrop remains supportive. Liquidity is plentiful, inflation is easing, rates are set to fall, and corporate earnings are growing. Yes, all of these components carry risk, but those risks have not landed yet.

Bull markets rarely die of old age. They die when liquidity tightens or inflation re-accelerates, and neither is flashing red today.

At the very least, hopefully this analysis has provided food for thought and a framework for assessing whether you should continue to ride the current bull market.

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned