Howard Marks: The end of globalisation

Howard Marks' latest memo has dropped and it is a doozy. Why?

Well, the Oaktree Capital legend has applied his decades-long "obsession with the concept of the pendulum" to two pressing, topical – but apparently unrelated – trends with global relevance right now: Europe’s energy dependence (made jarringly relevant given Russia's domination on supply) and US vulnerability to decades of offshoring, with special regard to semiconductors.

At a recent meeting of the Brookfield Asset Management board, a discussion of Ukraine triggered an association with another aspect of international affairs – offshoring – which I first discussed in the memo Economic Reality (May 2016). Thus the inspiration for this memo.

Marks argues in the memo (The Pendulum in International Affairs) that we may be seeing a swing away, at a corporate and international level, from globalisation toward onshoring. And he explores in detail the risk for investors this might entail but also the opportunities.

For those who want to read the memo in full, I have attached a PDF to this wire. If you would like to listen to the memo you can do so here

In this wire, I'll identify the key points in his thesis, and summarise the conclusion. But let's get one thing out of the way first: What's all this about a pendulum?

Glad you asked.

"Because psychology swings so often toward one extreme or the other," says Marks, " and spends relatively little time at the 'happy medium' – I believe the pendulum is the best metaphor for understanding trends in anything affected by psychology . . . not just investing.

Got it.

The first point: Europe's dependency on Russian energy was a green dream that created vulnerability

Marks kicked off by talking about how his memo came out of a board meeting whose first agenda item was "the tragic situation in Ukraine." While there were many different aspects to reflect upon - "human to economic to military to geopolitical" one thing stood out above all else: European reliance on Russian oil and gas. As Marks explains:

"The desire to punish Russia for its unconscionable behaviour is complicated enormously by Europe’s heavy dependence on Russia to meet its energy needs; Russia supplies roughly one-third of Europe’s oil, 45% of its imported gas, and nearly half its coal.

"Since it can be hard to arrange for alternative sources of energy on short notice, sanctioning Russia by prohibiting energy exports would cause significant dislocation in Europe’s energy supply," Marks says.

"Curtailing this supply would be difficult at any time, but particularly so at this time of year, when people need to heat their homes."

Marks' point is that Russia's biggest export (worth an estimated $20 billion a month) "is the hardest one to sanction, as doing so would cause serious hardship for our allies ... which greatly complicates the process of bringing economic and social pressure to bear on Vladimir Putin."

OK. So how much does Europe depend on Russian energy? More than a lot.

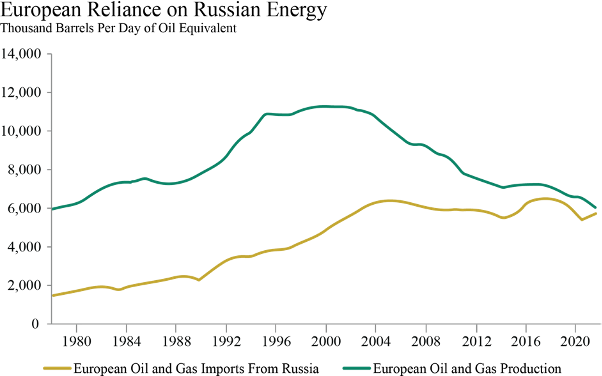

Marks began by pointing out "Europe uses far more energy than it produces and makes up the difference through imports. Russia, on the other hand, uses far less than it produces, leaving the remainder to generate economic and strategic gains."

While Putin ramped up oil and gas and nuclear energy production, doubling the latter to minimise domestic gas use, “Europe, led by Germany, shut down its nuclear power plants, closed gas fields, and refused to develop more through advanced methods like fracking.

The numbers tell the story best.

- In 2016, 30% of the natural gas consumed by the European Union came from Russia.

- In 2018, that figure jumped to 40%.

- By 2020, it was nearly 44%

- By early 2021, it was nearly 47%.

"European production peaked about 20 years ago and has almost halved since then, ending up near where it was in 1980. In the same roughly 40-year period, imports from Russia have tripled, meaning they’re now roughly equal to Europe’s production."

(Source: BP, Gazprom, Eurostat, Perovic et al., Russia Federal Customs Service. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management calculations, 2021.)

So why did Germany give up on self-reliant domestic energy production?

Marks argues it was Europe's desire to be more ecologically responsible at home that drove the increase in imported energy."In addition to limiting their production of oil and gas, some nations (especially Germany) reduced their use of nuclear power generation – which could arguably offer the best energy option by providing large-scale power production without emitting greenhouse gases – in a concession to those who consider nuclear power unsafe or environmentally unfriendly.

In 2000, around 30% of Germany's electricity came from nuclear sources, Marks said. In 2020 it was 11%. And at the end of last year, it closed half of its last six reactors. By 2022 they will all be shut down.

All of which amounts to an unconscionable security risk

"Choosing to count on a hostile neighbour for essential goods is like building a bank vault and contracting with the mob to supply it with guards. But that’s what happened."

The second point: Global supply-chain disruptions are leading to on-shoring

Marks argued the recent weakness of global supply chains has driven inflation and led to many companies reviewing how to shorten their supply lines "and make them more dependable, primarily by bringing production back onshore".

This constitutes a major reversal of a multidecade trend for offshore production, mostly to Asia, and its cheaper labour pool. A key driver in globalisation the process made manifest economic sense: emerging nations grew, there were savings across the board, and competition created lower prices for consumers.

But, argues Marks, "the supply-chain disruption that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the shutdown of much of the world’s productive capacity, has shown the downside of that trend, as supply has been unable to keep pace with elevated demand in our highly stimulated economy."

"At first glance, these two items – Europe’s energy dependence and supply-chain disruption – may seem to have little in common other than the fact that they both involve international considerations. But I think juxtaposing them is informative . . . and worthy of a memo."

Juxtaposing Europe's dependency on Russian energy with US dependency on foreign-made semiconductors

As Marks points out, Globalisation is enabled by offshore manufacturing, which allows production "to be performed where the costs are lowest" and drives up profits. The impact of Globalisation in the past 25 years or more has been profound.

Semiconductors, Marks says, "present an outstanding example of this trend."

Many of the most important early developments in electronics – transistors, integrated circuits, and semiconductors – took place at US companies such as Bell Labs and Fairchild Semiconductor. In 1990, the US and Europe were responsible for more than 80% of global semiconductor production. By 2020, their share was estimated to be only around 20% (data from Boston Consulting Group and the Semiconductor Industry Association).

But today, "Taiwan (led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)) and South Korea (essentially Samsung) have taken the place of the US and Europe as the largest producers of semiconductors."

“TSMC and Samsung are the only companies capable of producing today’s most advanced 5-nanometer chips that go into iPhones.”During the pandemic, supply was rocked by shutdowns and a devastating drought in Taiwan - but demand continued to soar, resulting in a crippling chip shortage, and delays between order and delivery of nearly six months

The impacts are considerable:

The chip shortage is a boon to semiconductor companies, but downstream firms are struggling. Global automakers are set to make 7.7 million fewer cars in 2021, which translates into a $210 billion hit to their revenues. Consumer electronics have taken a blow as well, with popular products like the PlayStation 5 console in short supply.

So what's the connection? (Clue: it's to do with security)

US companies’ foreign sourcing of say semiconductors is not the same as Europe’s energy emergency, but:

"Both are marked by an inadequate supply of an essential good demanded by countries or companies that permitted themselves to become reliant on others.

"And considering how critical electronics are to US national security – what today in terms of surveillance, communications, analysis and transportation isn’t reliant on electronics? – this vulnerability could, at some point, come back to bite the U.S. in the same way that dependence on Russian energy resources has the European Union."

European dependency on Russian energy and US reliance on overseas production of vital semiconductors just happen overnight. According to Marks:

"Just as Europe allowed its energy dependence to increase due to its desire to be more green, US businesses came to rely increasingly on materials, components, and finished goods from abroad to remain price-competitive and deliver greater profits."

Marks nominated the fall of the Berlin Wall and Soviet Communism, a feeling nuclear war was only a distant possibility and the relative absence of large scale multinational conflicts as contributing to "a huge swing of the pendulum toward globalization and thus countries’ interdependence. Companies and countries found that massive benefits could be tapped by looking abroad for solutions, and it was easy to overlook or minimize potential pitfalls."

As a result, in recent decades, countries and companies have been able to opt for what seemed to be the cheapest and easiest solutions, and perhaps the greenest. Thus, the choices made included reliance on distant sources of supply and just-in-time ordering.

What does this all mean for us now?

Marks concludes his memo thusly, and is worth quoting in full:

"The recognition of these negative aspects of globalization has now caused the pendulum to swing back toward local sourcing. Rather than the cheapest, easiest and greenest sources, there’ll probably be more of a premium put on the safest and surest.

For example, both US and non-US companies have announced that they intend to build new foundries to produce semiconductors in the US.

And I imagine many US importers of materials, components and finished goods are looking for sources closer to home. Similarly, it’s now less likely that Germany will follow through on its plan to turn off its three remaining nuclear reactors on 31 December and more likely that it will reactivate the three it retired at the end of 2021 (and perhaps, with the rest of Europe, recalibrate the balance between energy imports and domestic energy production).

If the pendulum continues to move for a while in the direction I foresee, there will be ramifications for investors.

Globalization has been a boon for worldwide GDP, the nations whose economies it has lifted, and the companies that reduced costs by buying abroad.

The swing away will be less favourable in those regards, but it may (a) improve importers’ security, (b) increase the competitiveness of onshore producers and the number of domestic manufacturing jobs, and (c) create investment opportunities in the transition.

For how long will the pendulum swing away from globalisation and toward onshoring? The answer depends in part on how the current situations are resolved and in part on which force wins: the need for dependability and security or the desire for cheap sourcing."

Other reading from Marks on the concept of the Pendulum

As Marks noted, "the following is only a partial list of my writings on the subject". (Please note I have edited some of his annotated remarks below for clarity and length.)

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

And you can follow my profile to stay up to date with other wires as they're published – don't forget to give them a “like”.

5 topics

Matt Buchanan is a former Head of Content at Livewire Markets. Matt is an avid investor and a big fan of the Livewire community, which he first joined in 2017.

Expertise

Matt Buchanan is a former Head of Content at Livewire Markets. Matt is an avid investor and a big fan of the Livewire community, which he first joined in 2017.