Lost in translation - Investing in private markets

LGT Crestone

Alternative investments continue to be prominent in the portfolios of some of the world’s most sophisticated investors, including sovereign wealth funds, endowments and pension funds. Australia’s own Future Fund is a prime example, with more than 40% invested across hedge funds, private equity and real assets, whilst global family office groups are in a similar position. UBS’s recently published Global Family Office Report 2019 also reported alternative assets in excess of 40%, with year-on-year increases in both private equity and real estate.

So, if institutional investors have been successfully investing in private equity for decades, why have private clients been slower to follow suit? In this article, we look at the benefits of investing in private equity, some of the challenges facing private clients, and potential solutions to overcome these challenges.

The benefits of investing in private equity

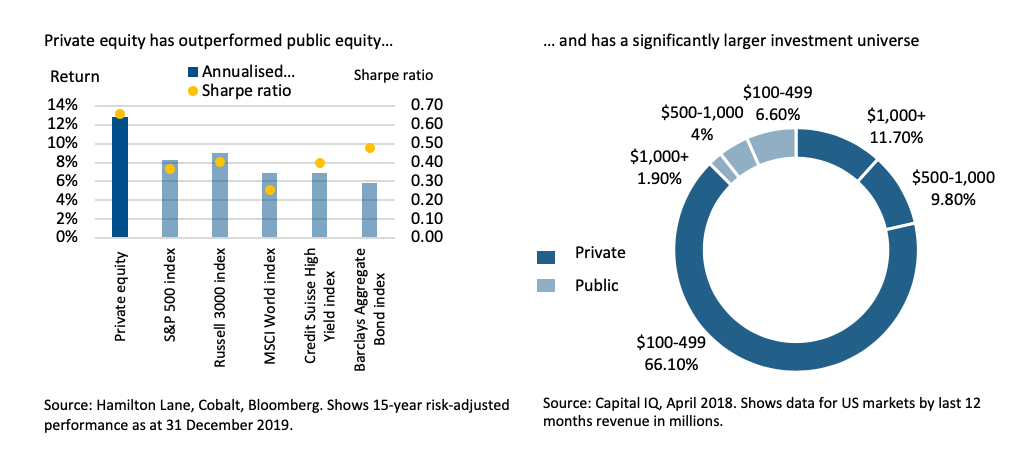

Institutional increases in private equity allocations have been quite consistent in recent years. This has been fuelled in part, by two things. Firstly, the well-cited persistent outperformance over public equities, as shown in the left-hand chart below; and secondly, a significantly larger investment universe, and thus diversification opportunity, as shown in the right-hand chart. The right-hand chart highlights just how sizeable the private company universe is compared to its more renowned (public) younger sibling.

So, why are private clients not investing like institutions?

Despite the benefits of investing in private equity, access can be a challenge for private clients. Private equity managers typically require sizeable minimum investment levels, which can force investors to carry too much portfolio concentration in terms of investment geography, sector and financing stage. This is also exacerbated by the greater dispersion of returns between private equity managers (and therefore greater manager selection risk), not to mention often relatively expensive fee structures and liquidity parameters that do not align to the way in which private clients typically allocate capital. Let’s explore these challenges in a little more detail.

David versus Goliath–hitting lofty targets

Investing in private markets broadly is more nuanced than public market investing. If you have a favourable view on Amazon or Apple, you can simply buy shares on market. To buy a private company, however, takes time—private opportunities need to be sourced, due diligence carried out, then structured and funded, typically with both equity and debt. As a result of this dynamic, private market investment vehicles are structured with drawdown models where fund managers call capital only when needed, as opposed to taking full payment of investors’ commitments upfront, as is the case when buying a (listed) global equity fund. This model prevents cash from sitting on account with the fund manager waiting to be deployed. Instead, it remains the responsibility of the investor to manage that cash whilst awaiting deployment.

Sounds reasonable, but here is where it can get impractical for private clients. These investment vehicles come with sizeable investment minimums typically ranging from $1 million to $20 million per investor. Smaller minimums are viable but the administrative burden for fund managers to cater for ongoing capital calls (for say, 1,000 investments of $100,000 relative to 10 investments of $10 million) is simply not practical. Ultimately, private markets investments are designed for Goliath, not David.

Di-worse-ification – diversifying portfolios is not always that easy

Let’s explore this further within a portfolio construction context for a wealthy individual or foundation with $20 million of investable assets. Using our balanced strategic asset allocation (SAA), we would suggest an allocation of 7% (or $1.4 million) to private equity. With this sum, we could feasibly invest in a single smaller global or US buyout fund—and perhaps a domestic mid-market equivalent where the investment minimum may be under $1 million.

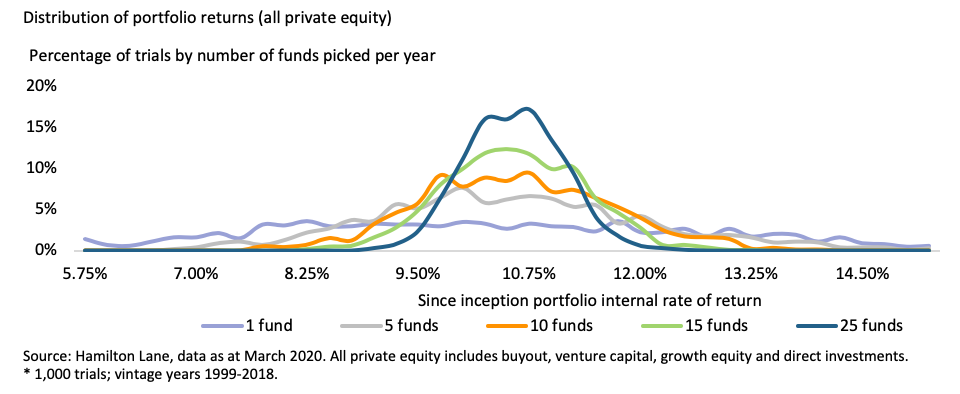

We would expect these investments to build to a total portfolio of approximately 20-30 companies over a number of years. However, given the breadth of the opportunity set, it is unlikely that these two investments would provide adequate geographic or sectoral diversity, let alone be able to diversify across financing stage (e.g. venture, growth capital, buyout). Is this a sufficiently diversified private equity portfolio? We would suggest not, and the data certainly shows that we should have more fund diversification to improve the probability of achieving our desired returns from this sub-asset class, as the below chart shows. That said, even if we take the view that the correct areas to invest in have been identified, and thus we are not concerned about the sizeable gaps in the broad portfolio exposures, the next issue is one where the data speaks for itself.

Click to enlarge image

Click to enlarge image

Mind the gap – the perils of manager selection

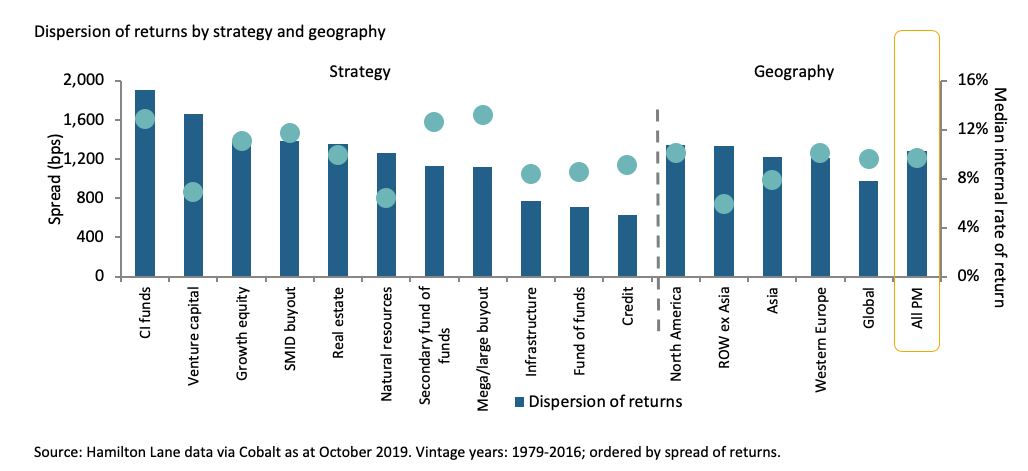

While you will rarely find a manager that doesn’t claim to be top quartile, manager dispersion in private equity and alternatives broadly is much higher than in traditional assets. That is to say that the difference in performance between the best, median and worst performing managers is significantly wider, meaning that picking the wrong manager in private equity is likely to have a far greater impact on returns than for public equity (fund) equivalents. As an example, if we take small to mid-cap buyouts (likely where our two funds would fall) shown in the chart below, the median return for the strategy is 11.8%, whilst the difference between the top and bottom performing managers is substantial at 13.8%.

With capacity for only two managers in our example portfolio, how do we mind this gap, especially when many of the best performing fund managers are often hard to access?

Click to enlarge image

Click to enlarge image

In-N-out–liquidity not burgers

So, we have established that private equity funds are not particularly accessible to private clients and, even if they were, clients are still forced to compromise and run some meaningful diversification and manager selection risks in our two-fund portfolio. That aside, we do need to touch on a number of other elephants in the room, namely fees and liquidity. Fees can be a lengthy discussion so, for now, we will point to the numbers and pose a question to you in the break-out box at the end of this piece. Liquidity, however, is critical to this specific conversation.

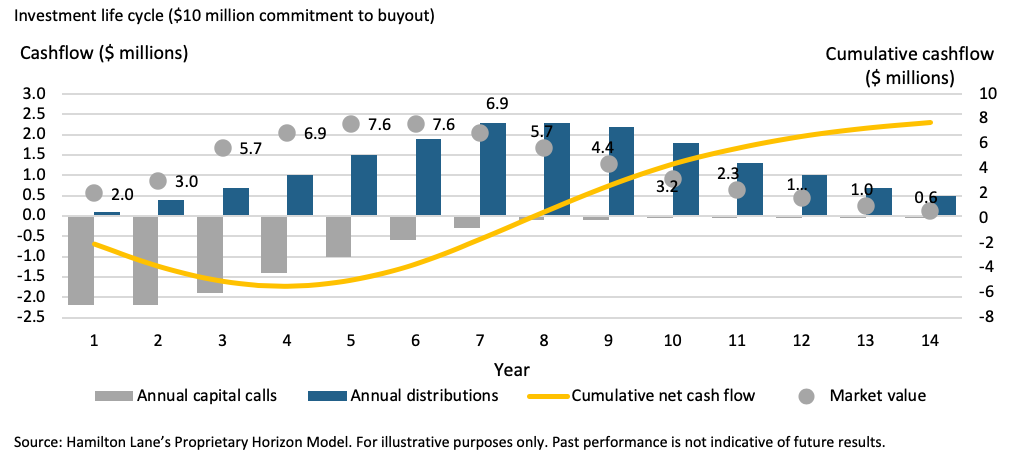

Whilst illiquidity, or the lack of outbound liquidity (i.e. getting money back), tends to attract the most debate, this is ultimately a discussion around the time horizon of an investment strategy and thus the level of illiquidity an investor and their portfolio can tolerate. It is also often somewhat misunderstood given fund terms are often stated at 10+ years with multiple extension options. In reality, the cash weighted life of a private equity fund is normally far less, with the chart below showing just that. To simplify the example, based on history, the maximum out-of-pocket cash can be roughly 55% of the commitment, cashflow is positive from year five, and the full initial commitment is returned in the form of distributions by years seven to eight.

If we use the same chart again in the context of our two-fund portfolio, a commitment today would result in full deployment of capital in the next three to six years, meaning that investors have no private equity exposure today, and may not actually reach the target SAA of 7% even after both funds are fully drawn (the fund example shows maximum exposure peaking at 76% of the commitment). This is a result of the funds making distributions following underlying portfolio company exits. Simply put, commitment does not equate to exposure.

Maintaining a target weight in (invested) private equity is actually very difficult, unless investors are able to over-allocate and appropriately manage investment pacing and cashflow requirements through the cycle. This is a complex task for sizeable institutions, let alone private clients and their advisers.

That intentionally leads on to what we believe to be an under-appreciated aspect of liquidity in private markets, particularly for private clients—that being the inbound liquidity. Simplistically, this is the ability for private clients to allocate into a vehicle frequently and over a reasonable period of time (as opposed to a single closing date), and preferably into a portfolio that is already invested, much like any traditional asset class portfolio.

This is important as it enables private clients to allocate when it suits them and at the optimum time for their portfolio, as opposed to patiently holding cash awaiting deployment. Most private clients are not like institutional investors who are wholly focussed on managing their portfolio. As such, they should not be held captive to a given manager’s fundraising cycle. Ultimately, private equity and private markets more broadly need to evolve to facilitate a different style of investor—we need to translate institutional product into private client solutions.

Emerging from the darkness

Despite the challenges of accessing private markets, there is light at the end of the tunnel. That is to say that there are global wealth firms, alternative asset managers and emerging technology platforms working to develop solutions for private clients investing into private markets. Over the last few years, we have seen many such solutions emerge providing exposure to, for example, domestic private debt, domestic infrastructure, global private equity and global property, all within open-ended investment vehicles. These vehicles offer quarterly, monthly or, in some cases, daily liquidity (both in and out) with pre-defined rules around subscription and redemption volumes to ensure portfolio construction remains optimal for investors. Clearly, the open-ended nature of these strategies helps address the liquidity issues discussed, but diversification is the other key component of these new entrants. One such example launched only last year offers exposure to 26 general partners (investment managers) who, combined, are invested in 172 underlying buyout, growth and venture portfolio companies across nine industries worldwide. This is a far cry from the two-fund portfolio discussed earlier.

As global private markets continue to evolve across private equity, private

debt, venture capital and unlisted real assets, we expect to see more

investment solutions appear that present more practical solutions for private

clients. We will continue to be at the forefront of these developments as we

seek to open up the institutional investment market to the breadth of our client

base and others.

The private equity fee debate

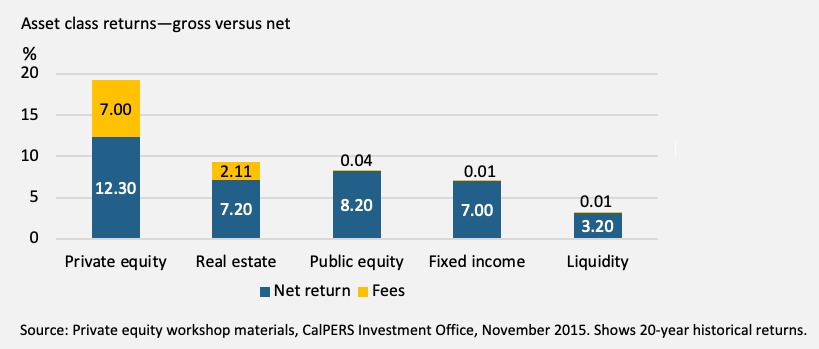

Noting that the following chart implies passive investments for equities and fixed income, there are two opposing views when it comes to fees and performance: The investor’s view: “Wow, private equity is crazy expensive!”; The manager’s view: “Wow, net private equity returns outperform everything else by at least 400 basis points.”

Both sides make a legitimate point. What’s your take?

Diversify your portfolio through Alternatives

Crestone Wealth Management offers access to a range of strategies in the alternatives space, including hedge funds, private equity and venture capital, as well as structured products, warrants and other derivatives. Click the 'Contact' button below to find out more.

2 topics

1 contributor mentioned

Martin is responsible for delivering and maintaining Crestone’s investment offering for hedge funds, private equity and real assets, where he sources, performs due diligence and structures alternative investment solutions for Crestone’s client base.