Shifting global trade patterns bring new opportunities.

In his latest investment insight, Rob Lovelace, Vice Chairman of Capital Group, explores the profound changes occurring in global trade and key themes investors should consider.

What will global trade and commerce look like in the coming years, and how will it influence the investment landscape? This question has moved to the forefront of investors’ minds as the US administration seeks to renegotiate relationships with key economic partners – most notably China, where the US is on the verge of a fundamentally new moment on trade. As the Middle Kingdom’s economic power grows and its global ambitions become clearer, a new consensus is emerging in Washington that a more hard–headed approach to both trade and geopolitics is merited. In Britain, too, the government will work towards new or modified tariff and trade regimes that can preserve its commercial ties with Europe, even as it seeks a new national identity independent of the European Union.

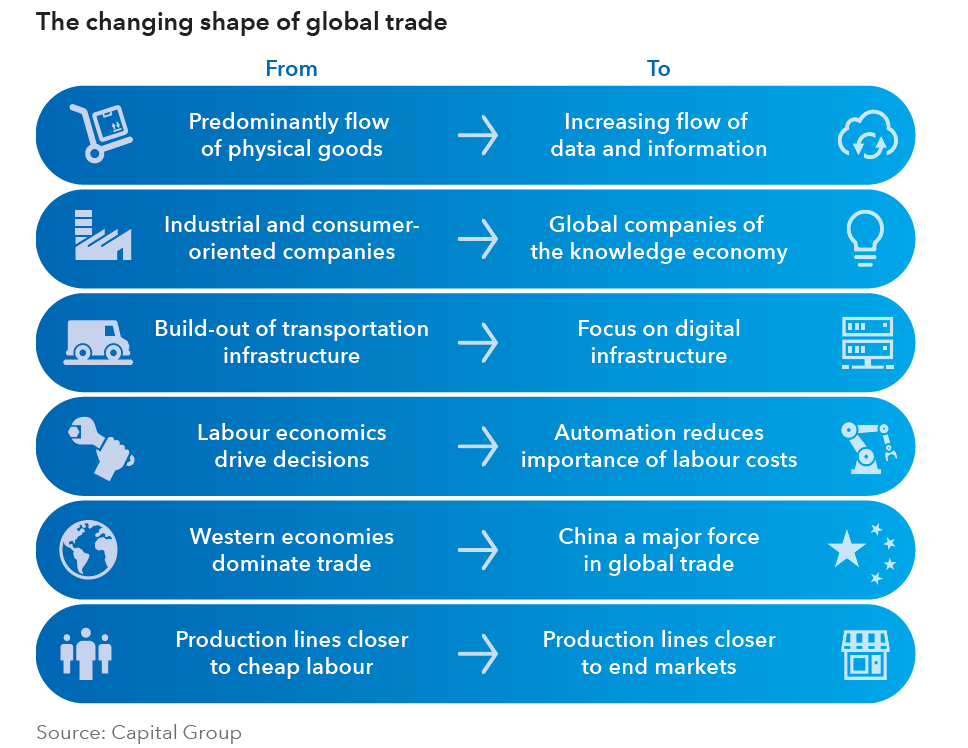

In many ways, the contours of international commerce have already undergone a profound transformation over the past two decades. If the 20th century was defined by a phenomenal rise in the transfer of goods and industrial commodities, the 21st century is being characterized by the rapid digitisation of services and the increasing automation of manufacturing. It is the advancement in technologies and how they continue to reshape industries that will determine the future of global business as much as political negotiations.

China’s rise as an economic power and its major influence on global growth is another important aspect of the shift in the world order. The US and China have economic and financial interdependencies that are deep and complex, and, in our view, will likely lead to terms of trade that are ultimately accommodating and beneficial for all parties.

Trade negotiations can often be characterised by abrasive rhetoric as participants on all sides try to extract maximum benefits, and what we see unfold in the political arena over the next few months or couple of years may not be that different. While negotiations of this type are by their nature unpredictable, the outcomes need not be extremely positive or negative for one side or the other. It is our job to consider the various probable scenarios and invest accordingly. In the following pages, we discuss some of these issues in greater detail.

The digital transformation knows few boundaries

The very notion of a global company has evolved over the past two decades. There are the old–line multinational behemoths dominant in commodities, heavy industrials and consumer products. But there is also an entire generation of new global companies that have emerged over the past two decades that are giants in the digital economy. Alphabet (Google), Amazon and Priceline are among the most prominent examples.

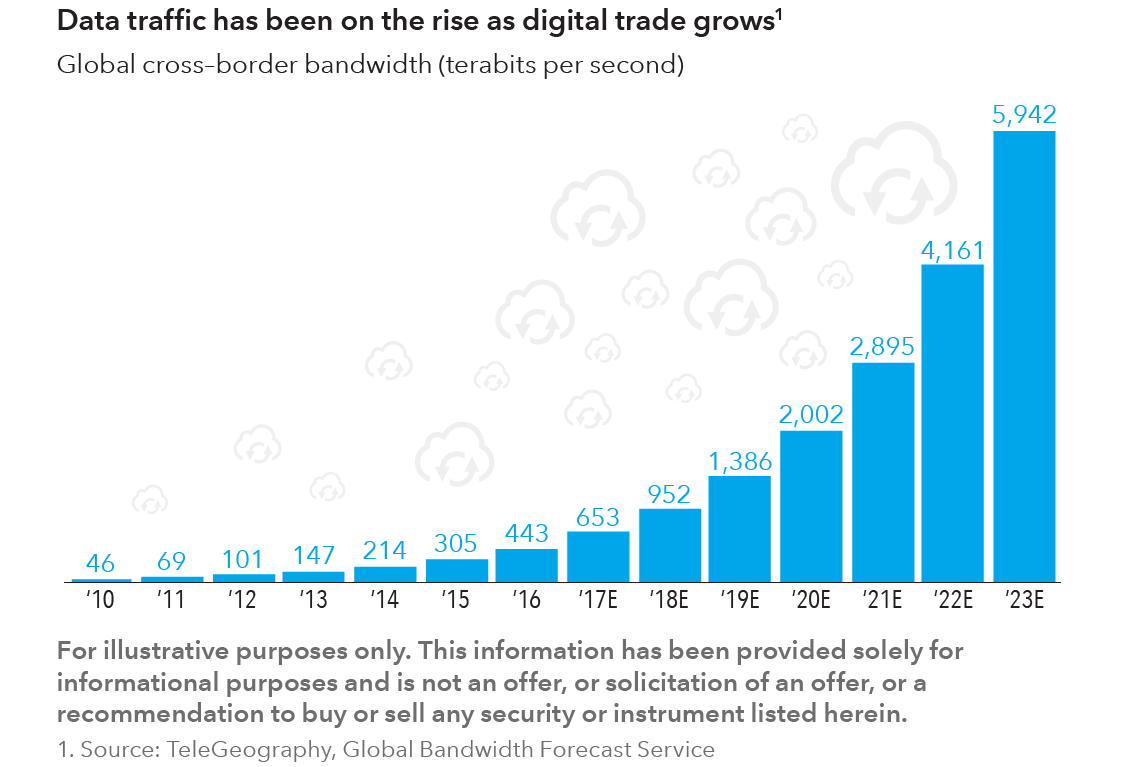

Many parts of the digital economy are not captured in traditional metrics of international trade and gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Similarly, many aspects of the digital economy cannot be easily dictated by trade agreements or tariff regimes. As an indicator of the expansion in this area, cross–border digital traffic has grown 40 times larger since 2007 and is projected to grow by another 13 times in the next seven years.1 The impact of trade renegotiations is likely to be more severe for manufacturers than these companies.

Digital platforms are also changing the economics of doing business across borders, bringing down the cost of transactions. Enterprise software solutions and cloud computing are enabling firms to innovate new products and solutions in multiple locations, with faster speed to market. Small– and medium–sized businesses have been able to gain global access by using digital platforms such as Amazon, eBay, Facebook and Alibaba to connect with customers and suppliers in other countries.

As their size grows, issues related to digital commerce and intellectual property are gaining prominence in trade agreements. Similarly, regulators are seeking greater purview over issues of privacy, location of servers and access to online information and services. These issues will continue to get attention as we see the increasing digitisation of ideas, information and commerce.

Supply chains are entrenched and not easily uprooted

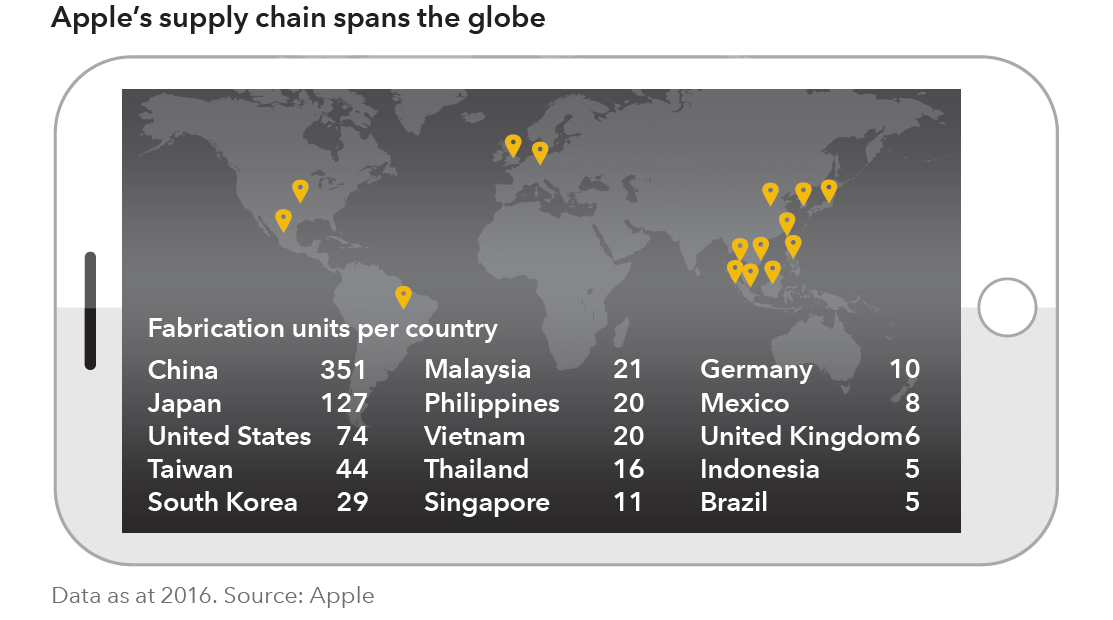

Supply chains today are deeply entrenched across the globe and will not be easily uprooted. Take Apple as the most obvious example. Its supply chain spans 30 countries, and it is a master of using that to its advantage, sourcing suppliers that can turn out parts in the most cost–effective way while still adhering to the company’s quality requirements. Apple’s strategy is motivated by the need to scale and manage supply chain risk rather than just cost. We could see the company further diversify its sourcing across countries to be closer to end markets, including bringing some production to the US.

Moreover, as supply chains have become global, companies have gained specialisation and scalability that is difficult if not impossible to replicate. For instance, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) dominates certain areas of the computer chip market that are nearly impossible to recreate in design or scale. Similarly, Broadcom dominates the market for smartphone chips.

Visa and MasterCard control the credit card payment system nearly worldwide. Three companies — Novartis, Amgen and Roche — account for half of the global sales of cancer drugs. Given their dominance in their respective industries, we call these companies global champions.

In some industries, companies are willing to absorb higher costs because the long–term benefits of operating in certain locations outweigh the near–term burden. Caterpillar, General Motors and Ford are just a few of the large US companies that have said they remain committed to restructuring plans that involve moving production to Mexico, which has established itself as a premier auto and auto parts manufacturing centre over the years. About 90 of the world’s top 100 auto parts makers have production operations in the country. The facilities are concentrated in five Mexican states, reducing transportation costs. Mexico also has free trade agreements with countries across the world that give it access to most major markets.

China has extraordinary influence on trade and companies’ growth prospects

China’s rise as an economic power over the past two decades continues to have a profound impact on global trade. Its role as the world’s largest manufacturer of all kinds of goods is well–known. Its rapid urbanisation has created a boom in the property market. As a result, it has an outsized influence on the commodities cycle. Over the past decade, China has also become the largest growth market in the world for a vast array of industries, ranging from robotics and autos to aeroplanes and smartphones. For example, in 2016 China accounted for 30% of global robotics sales.2 It is the fastest–growing market for Starbucks, which is targeting 5,000 stores in the country by 2021. Despite a deceleration in economic growth, China remains the most important driver of revenue and earnings growth for many companies around the world. For us to evaluate the success of the global efforts of many companies, understanding their China strategy is critical, and we dedicate substantial resources to that effort, both on the ground in China and around the world.

Trade negotiations between China and the US continue to be important to monitor. China’s relationships with the US are multidimensional and deep, with many mutual interdependencies. The US administration has made noise on reducing the trade deficit with China, which stood at US$375 billion in 2017, with exports at US$130 billion and imports at US$505 billion.3 A large chunk of the imports are from US manufacturers that have set up assembly lines and factories in China. Meanwhile, China relies on some key high–tech products produced only in the US. It is seeking to reduce this dependence by developing its own semiconductor chip industry and electronic payments systems. But these will take time.

There are substantial links on the financial front as well. China holds over US$1 trillion in outstanding US government debt.4 Meanwhile, Chinese companies, such as Alibaba, Baidu and JD.com, raise capital in the US financial markets through initial public offerings and offshore US dollar bonds.

China’s influence leads to more trade for emerging markets

China’s engagement in trade negotiations may also help the central government in its own ambitions to open up its economy. It could provide China’s leadership with the platform it needs to implement much–needed reforms. Any negotiations will have multiple layers of relationships to consider, and businesses with interests on both sides are likely to influence new deals.

While the negotiations may be characterised by bouts of potentially unfriendly rhetoric, ultimately, we think any new trade agreements are likely to have accommodations for both sides, given the mutual economic and financial dependencies. The impacts are likely to be company–specific and any investment strategy must be able to address the volatility with a view on the long term.

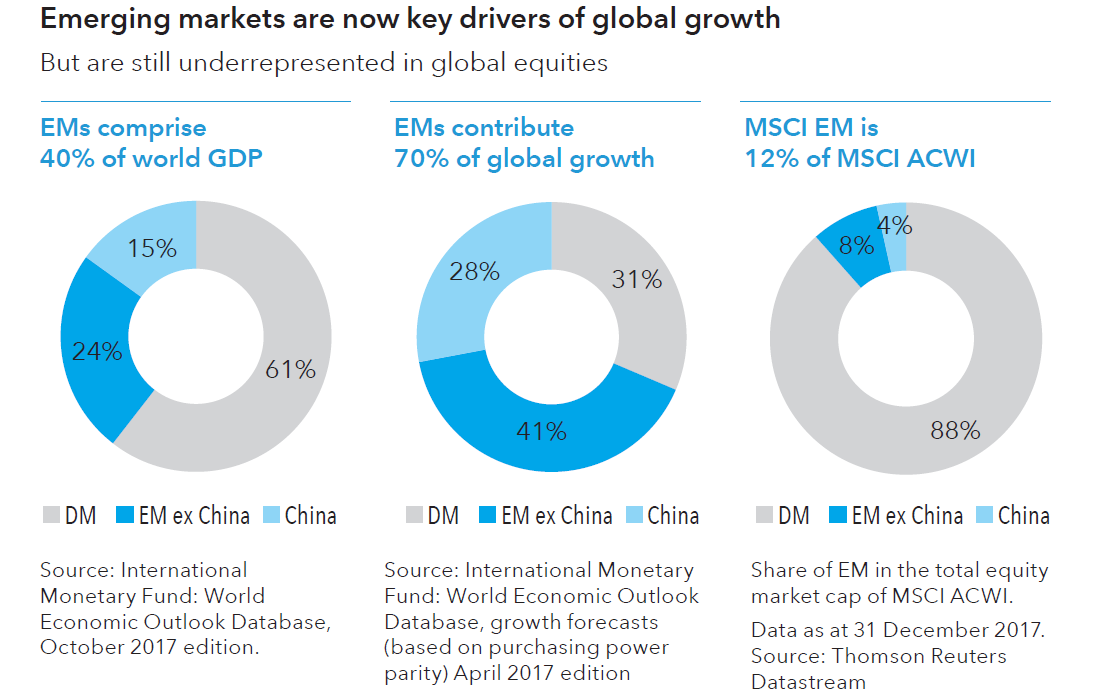

China’s influence has also led to greater trade by emerging markets among themselves and with developed economies. In 2017, 35% of developed–market exports went to emerging markets, and 41% of the trade by emerging markets was among themselves, according to the latest figures available from the International Monetary Fund (October 2017). Emerging markets’ share of global GDP has risen significantly, to 40% of global GDP (see next page).

With domestic demand rising to become a greater share of total output, we are seeing regional industry leaders emerge in Asia. Thai Beverage, Lenovo, Larsen & Toubro, Sun Pharmaceuticals and Tencent are just a few examples. Many of these companies are less vulnerable to demand from the US and Europe.

Moreover, as the global economy gains momentum — especially the industrial economy, and, with it, commodities — emerging markets should benefit. Now we are seeing a recovery in profit growth. Earnings for emerging market companies increased to 30% in 2017.5

Labour costs matter less as automation rises

There is no doubt that the tax benefits of operating in multiple jurisdictions have historically driven some of the decisions of multinationals in locating plants and production facilities. The low cost of labour has been another important factor. Both of these benefits could diminish in the coming years.

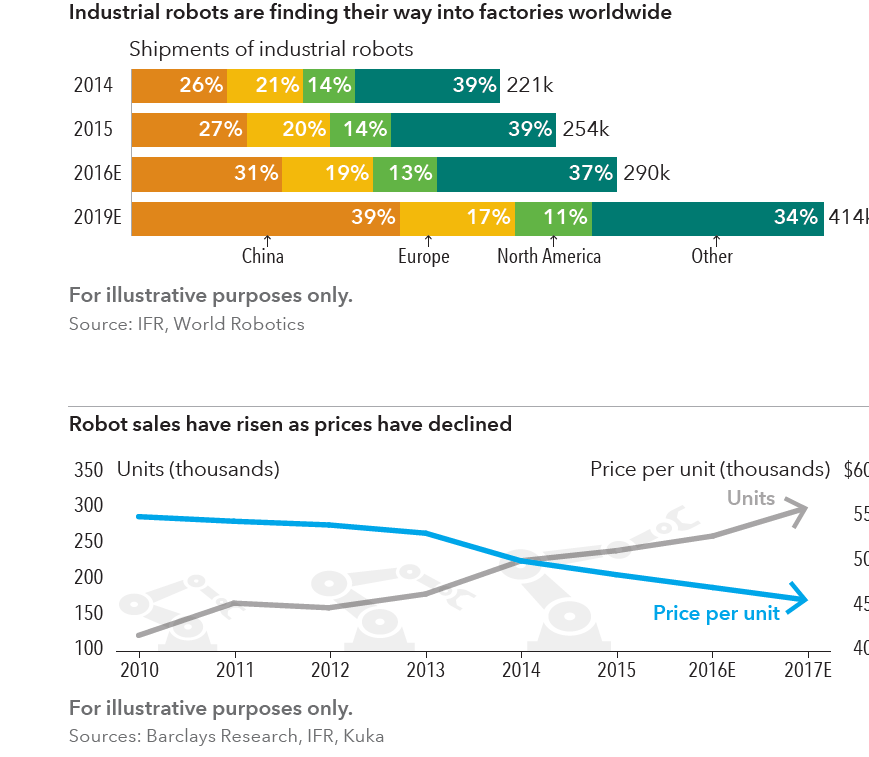

Rising wages in China are reducing the labour cost advantage that the country has enjoyed for the past three decades. More importantly, rising automation in production lines across a host of industries is likely to further diminish the benefits of any cross–border labour arbitrage. There were more than290,000 industrial robots sold in 2016, with most of the growth coming from China, according to the InternationalFederation of Robotics.

The economics of automation have hit a sweet spot, where costs of robotics systems are declining and capabilities are improving rapidly. China is also seeing a generational shift, with younger, better educated workers less willing to do repetitive, menial tasks. With automation reducing the importance of labour costs, we could see production moving closer to end–markets. It is this transformation in the economics of labour that could bring manufacturing and jobs to the US.

Many established multinationals like Unilever, Nestlé and Coca–Cola have been moving closer to end–markets over the years. They have devolved their operations to be much more local to gain a deeper understanding of local markets and compete with domestic companies. Coca–Cola’s CEO, referring to the company as a “multi–local business”, said at an earnings call that the company “distributes locally, sells locally and pays taxes locally”, and is not too concerned about any shifts in trade regimes.

Conclusion

Global commerce has been transformed over the past two decades. Global companies account for 80% of trade, 75% of private sector research and development, and 40% of productivity growth.6 We are likely to see global trade patterns evolve with the increasing digitisation of commerce and the likelihood of new trade, tariff and tax structures in many parts of the world. Shifts in economic and trade regimes and turning points in markets provide managers like us the opportunity to capitalise on short–term distortions in asset prices and to invest in select companies that we view to be winners over the long term.

Of course, not all global companies will thrive in this new environment. Fundamental research will be key. Nevertheless, successful multinational companies typically have innovative management teams, diverse sources of revenue and the resilience of solid balance sheets. These attributes offer the potential for future success.

Past results are not a guarantee of future results.

2. Source: International Federation of Robotics (IFR), World Robotics Report 2016

3. Data as at February 2018. Source: US Department of Commerce

4. Data as at December 2017. Source: US Department of the Treasury

5. Data as at January 2018. Source: I/B/E/S, Thomson Reuters Datastream

6. Source: Playing To Win: The New Global Competition for Corporate Profits. McKinsey & Company. September 2015

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned