The 26-question test that only 221 companies survive

Last week, I wrote about how performance chasing and our own investor biases can quietly sabotage even the most clever of portfolios. The piece resonated with some readers, sparking reflection on how much of investing success really depends on mastering our own psychology.

Not long after, I came across an episode of "Inside the Rope", where host David Clark sat down with Doug Tynan, Co-Founder and Chief Investment Officer at GCQ. Tynan has built both his career and his firm on one deceptively simple principle: discipline beats instinct. His secret weapon? The humble checklist.

In their conversation, Tynan explained how structured decision-making helps investors guard against the very behaviours that trip them up. It was a natural continuation of last week's theme, not just understanding your brain, but designing a process to keep it in check.

The psychology of process

For Tynan, investing is as much about psychology as it is about analysis. He credits Munger for shaping that view:

"Everybody’s got the same tools — the same accounts, the same newspapers, the same access to management teams. None of that gives you an edge. What actually does give you an edge is understanding psychology — especially your own weaknesses and biases.”

It's a philosophy that echoes the lessons from "Your brain vs your portfolio", the mind is both the engine and the enemy of investment returns. Checklists are Tynan's antidote, a tangible way to bridge self-awareness with action.

From the cockpit to the portfolio

His favourite analogy is aviation. Every pilot, from a crop-duster to an A380 captain, runs through a list before take-off and landing.

"There is never a situation where they skip those checklists - in fact, it's the law."

The brilliance lies in the simplicity: is the door closed? Are the tyres pumped? Are passengers seated?

Each step guards against human error born of familiarity and overconfidence, the same traits that plague investors.

"Whenever there's been an issue on an aircraft, engineers and psychologists review what went wrong and improve the checklist. That's the single most important reason why airline travel is the safest form of travel today."

At GCQ, the same logic applies. Every investment idea is tested through structured questions designed to prevent emotional or narrative-driven decisions.

"Transparency brings accountability. We show our entire portfolio and talk about all of our rules. Most of those rules are put in place to offset my weaknesses."

The 26-question checklist

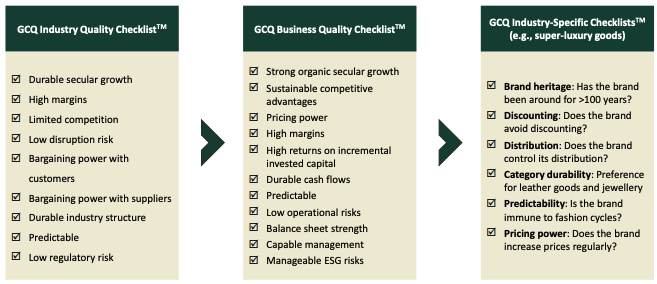

The firm's flagship "industry quality checklist" includes 26 questions, an investing pre-flight inspection. It starts broad: Does the industry have high margins and returns on equity? Is growth sustainable? Is regulation a risk? But one question stands out.

"Our toughest question is number six: Has this industry had any successful new competitor in the past 20 years? We're looking for industries that have all those positive attributes, but no competitor can come in."

That single filter excludes entire sectors, from fast-moving tech to hyper-competitive consumer categories, leaving only a handful of enduring franchises.

"Only 221 companies in the world across 20 different industries actually get through that question. It's an extreme form of quality control - one that's helped GCQ deliver around 30% compound annual returns since inception."

Why investors still overcomplicate

Despite the elegance of rules and repetition, Tynan admits resisting prediction is the hardest discipline of all.

"I pay almost no attention to trying to forecast the macro. I think you become a better investor when you resist trying to pick and time markets."

He recalls how even world-class investors blew up track records during COVID by betting on macro outcomes.

"Whenever stock pickers start to talk about macro or become epidemiologists, watch out. You're talking about something you know nothing about, but it's tempting and you don't intend to do it, but it's incredibly tempting. That's why it's so important at GCQ, we have these rules."

The temptation to do something, to act on the latest narrative, remains the most persistent behavioural trap.

The smell of success

To illustrate the power of competitive advantage and investor psychology, Tynan turns to an unlikely hero: WD-40. "It has a fantastic and irreplaceable brand name." The scent, unchanged since 1961, triggers memories of childhood.

"When someone smells WD-40, it triggers a childhood memory. Working with a parent or grandparent in the shed." Those emotional cues drive loyalty stronger than price.

"When you're reaching for a can of industrial lubricant, you're going to go for WD-40 regardless of price."

That insight sits at the intersection of behavioural finance and fundamental analysis, the very edge Munger taught. Proof that the strongest competitive advantages are often psychological as well as structural.

The quiet power of discipline

What stands out in Tynan’s approach is its humility. There’s no grand theory of where markets will go next, just a belief that process can outlast emotion. Investing, in his view, isn’t about predicting recessions or chasing trends. It’s about consistency, reflection, and the willingness to refine your own checklist every time you make a mistake.

“Transparency brings accountability,” he said, a line that could just as easily apply to our own portfolios as to a fund manager’s. Or, as he put it more simply, “We’re all there to serve our checklist and our process.”

That humility, the idea that structure, not instinct, drives consistency, may be the ultimate behavioural edge. Because in the end, investing success rarely belongs to the smartest or the fastest. It belongs to those disciplined enough to build systems that protect them from their own psychology.

As Charlie Munger famously said, “You don’t have to be smarter than the rest; you have to be more disciplined than the rest.”

4 topics

1 contributor mentioned