The Big Investor Lesson from the 7-Eleven Debacle

After working through 400 worker claims for back pay so far, the latest estimate is that another $100 million in claims is in the pipeline. For a company with earnings before interest and tax of $143 million in 2015 that’s a huge contingent liability. It’s not just going to be a one-off hit, the ability of 7-Eleven to sell new franchises has been greatly reduced given the profits of stores have been inflated by underpaying workers. There’s also more compensation being paid to franchisees whose stores are losing money. This is thought to be around 20% of stores, which even with the compensation are at risk of being closed.

The underpayment of workers is believed to have occurred at almost all of the 600 Australian stores with over 15,000 employees thought to have been underpaid. Staff were either paid below award wages, paid for less hours than they worked or were paid the right amount but then forced to give back some of their wages to the franchisee. The effective rate of pay was typically around half of the award rate. Extrapolate those practices over 600 stores and employees were short changed by $50-80 million per year.

All of this was done with the full knowledge of senior management at head office. The initial claims of company executives that they did not know were rubbished by whistleblowers who said that the schemes to underpay workers were common knowledge. The wages were processed by head office, who also required stores to submit regular accounts and had access to CCTV footage that showed who was working when. Repeated investigations by the Fair Work Ombudsman on worker underpayments resulted in legal action from as far back as 2009.

Given all of the above, there’s obviously an enormous cultural problem at 7-Eleven. So what’s the takeaway? It’s that sometimes it takes only the most basic due diligence to smell a rat.

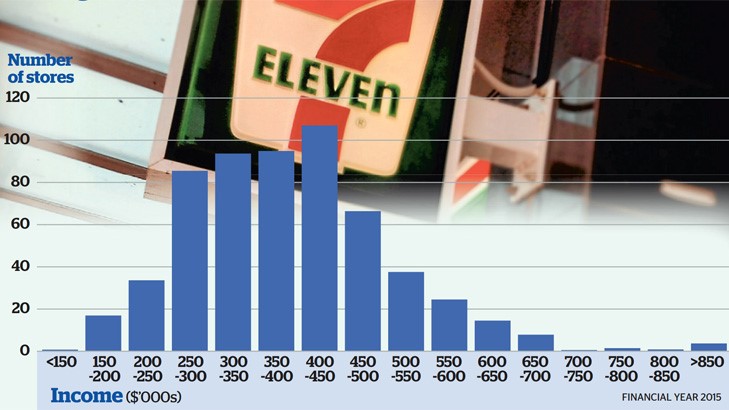

Assuming a store was staffed 24 hours a day, 365 days a year by one worker at minimum wages it would need to generate at least $600,000 of gross profit for the franchisee to make a minimal profit. Head office takes 50% of gross profits, the rest is then “income” for the franchisee to pay wages and other costs. As the graphic below from the SMH website shows over 20% of stores didn’t hit this benchmark. Head office was making money on these stores, but the only way for the franchisees to earn any meaningful return on investment was to defraud their workers.

Source: smh.com.au

Similar examples to this were the string of toll road failures in Sydney and Brisbane. The two toll roads in Brisbane, Rivercity and Brisconnections never had a chance, with ridiculous traffic forecasts needed to provide anything like a business case for investors. Crazy assumptions were put forward about the growth in traffic and the willingness of drivers to pay a toll to save a few minutes. The forecasts were so bad that when the roads opened with a toll free period, they still couldn’t hit the traffic forecasts.

As someone who was working out the debt of one of the toll roads at the time it wasn’t just equity investors that completely missed it. Dozens of banks had invested in the debt of these roads as well. Whilst the shares were crashing many of the banks wouldn’t admit there was a problem. They waited until months after the tolls were in place and traffic was a fraction of what was needed to pay the interest. At the same time I was estimating that the banks would recover 30-60% of their debt on pretty simple calculations, others were assuring all and sundry that debt would be repaid in full.

Investment outperformance is all about doing different things from the consensus. Despite almost everyone knowing this, many markets operate on the basis that someone else has done the work. Investors pile in, assuming safety in numbers. In some cases, the fact that you run the basic numbers is all that is needed to avoid an investment debacle.

Written by Jonathan Rochford for Narrow Road Capital on May 13, 2016. Comments and criticisms are welcomed and can be sent to info@narrowroadcapital.com

5 topics