The perfect storm creating supply chain issues

Fund manager quarterlies and stock broking strategy pieces are coming in thick and fast, all offering opinions about inflation. Everyone has a well-articulated argument as to why inflation is going to be sustained or transitory.

Rather than focus on the top-down perspective, we thought it would be more useful going to the coal face and leveraging our large investment team at Perpetual − who speak with hundreds of companies a year − to try and get a feel of what is going on at our investee companies.

In the last fortnight, we did one better and spoke to two dozen supply chain experts from both unlisted and listed companies.

Our goal is to get a snapshot of exactly what is going on through the supply chain and then use our judgement to work out how this will play out over the medium term.

“The supply chain is at breaking point and we are only just into October; I just don’t know how we are going to get to Christmas,” a logistics manager at a major supplier to supermarkets told us.

So what have we learnt?

We are in a perfect storm. Whereas in February this year there were pockets of inflation called out by the companies we interviewed (West Australian labour, used cars, timber), it seems to be much more widespread today. Our key learnings are:

This is consistent feedback. One major supplier to supermarkets and the food services channel said: “Usually we have 1-2 inputs with some degree of upward pressure, which was manageable now 90% of our inputs into products are up double digit.”

Both retailers and manufacturers are seeing cost push inflation from the following:

- Freight (2-5 times container shipping costs)

- Extra warehousing/distribution costs due to labour issues/required inventory build

- Anything with an oil base – plastic, resin, diesel

- Commodities – copper, meat, coffee, sugar, wheat, cotton, steel, timber, energy costs, petrol/diesel

- Labour – availability and productivity of labour is extremely tight. While there has yet to be an impact on unit cost of labour, the reduction in productivity is inflationary as it costs more to produce the same one unit of a good

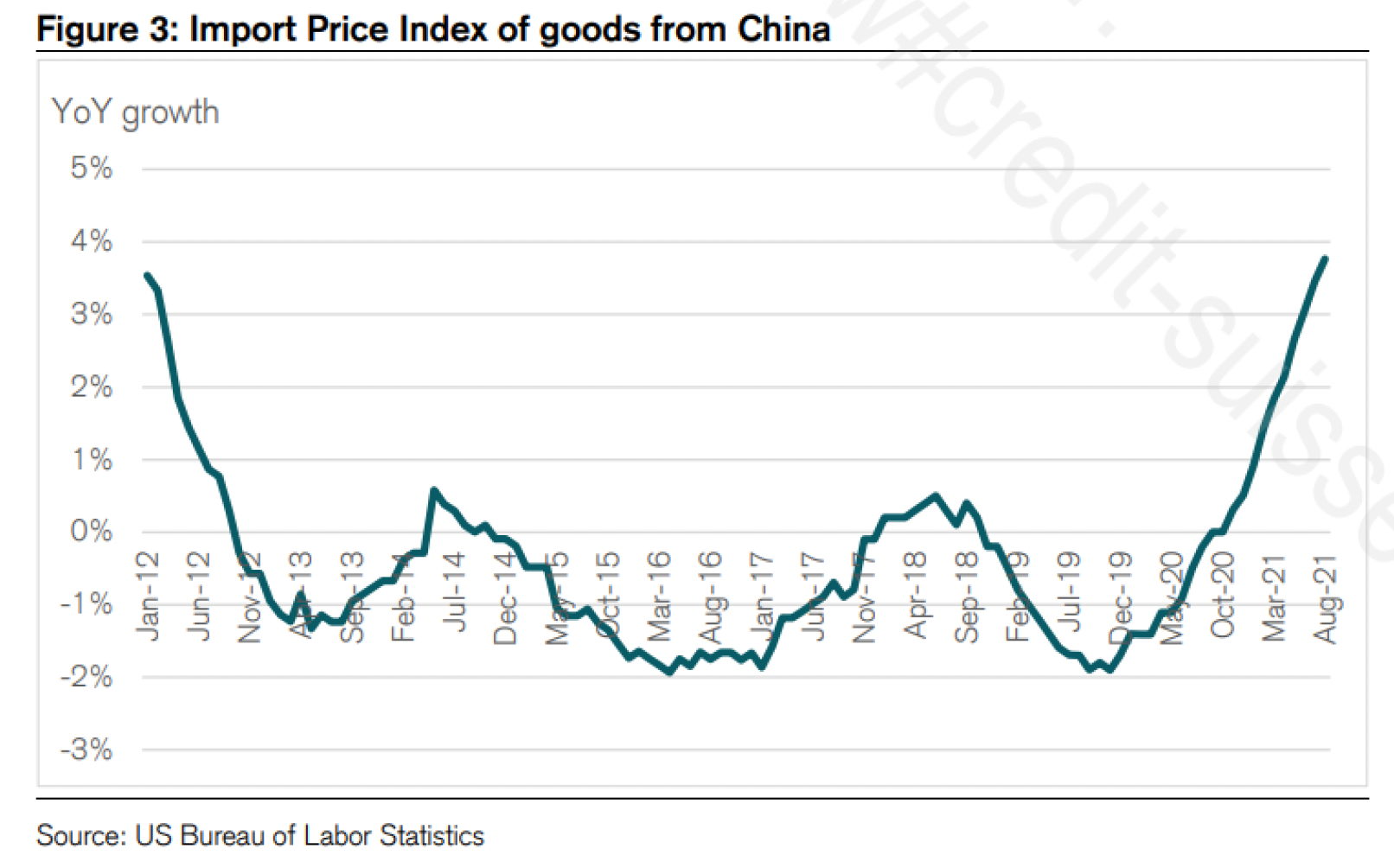

- Manufacturing costs in China – whether it be due to energy costs or higher labour costs, China is starting to export material levels of inflation.

Imports/exports are a nightmare

Even now, there are delays getting things into Australia from key supply regions like Vietnam or China. The issue in China was originally COVID shutdowns but now it is being impacted by the cost and rationing of power in the certain provinces.

Other issues for imports/exports at the moment are:

- Availability of containers

- Cost and availability of freight is off the charts

- Australian ports are already backed up, but this is about to get worse with Port of Melbourne stevedore strikes which could be up to a month long

- Scarcity of truck drivers is elongating delivery times and costs as well.

One retailer we spoke with has job ads out there for up to 1000 jobs which they are struggling to fill. One food manufacturer has 500 unfilled job ads. There is a complete scarcity of labour. This has been driven by a variety of factors:

- COVID rules: Even if a worker has been double vaccinated and has a negative test, he/she is required to isolate for a fortnight if they are a close contact. This has resulted in distribution centres and warehouses operating at materially below capacity.

- Seasonal labour shortages: Whether it be fruit pickers, hospitality workers or truck drivers, the lack of inbound tourists with working visas coming to Australia has stopped. This has created labour shortages in some crucial sectors.

- Jobseeker payments create disincentive to work. However, once the states reach 80% vaccination, these COVID disaster payments will likely end, which should increase some labour capacity.

- Refusal to get vaccination also restricts a certain subset of the labour force.

While there hasn’t been obvious widespread wage inflation as yet, the lead indicators of strong demand for labour combined with shortages are likely to feed into wage inflation in the future.

The main areas of scarcity are pallets, containers and port slots. This is resulting in the supply chain wanting to start to build inventory to higher levels than usual, given the seasonal peak in demand is yet to come.

While some of this will reverse as COVID-induced bottlenecks free up, we feel it is inevitable that there is a more permanent shift from “just in time” inventory management to “just in case” inventory management. This could result in a structurally higher inventory level than pre-COVID.

So what does this mean?

Over the last fortnight we have also spent a lot of time listening to management commentary from overseas companies on their quarterly earnings.

What is interesting is these supply chain issues are a world-wide phenomenon. This is unfortunate for Australia, as there is unable to be slack provided from other parts of the world.

The September quarter CPI in Australia was 3%. While high, most explained it away as being impacted by base effect (i.e. last year was so low) and transitory price increases.

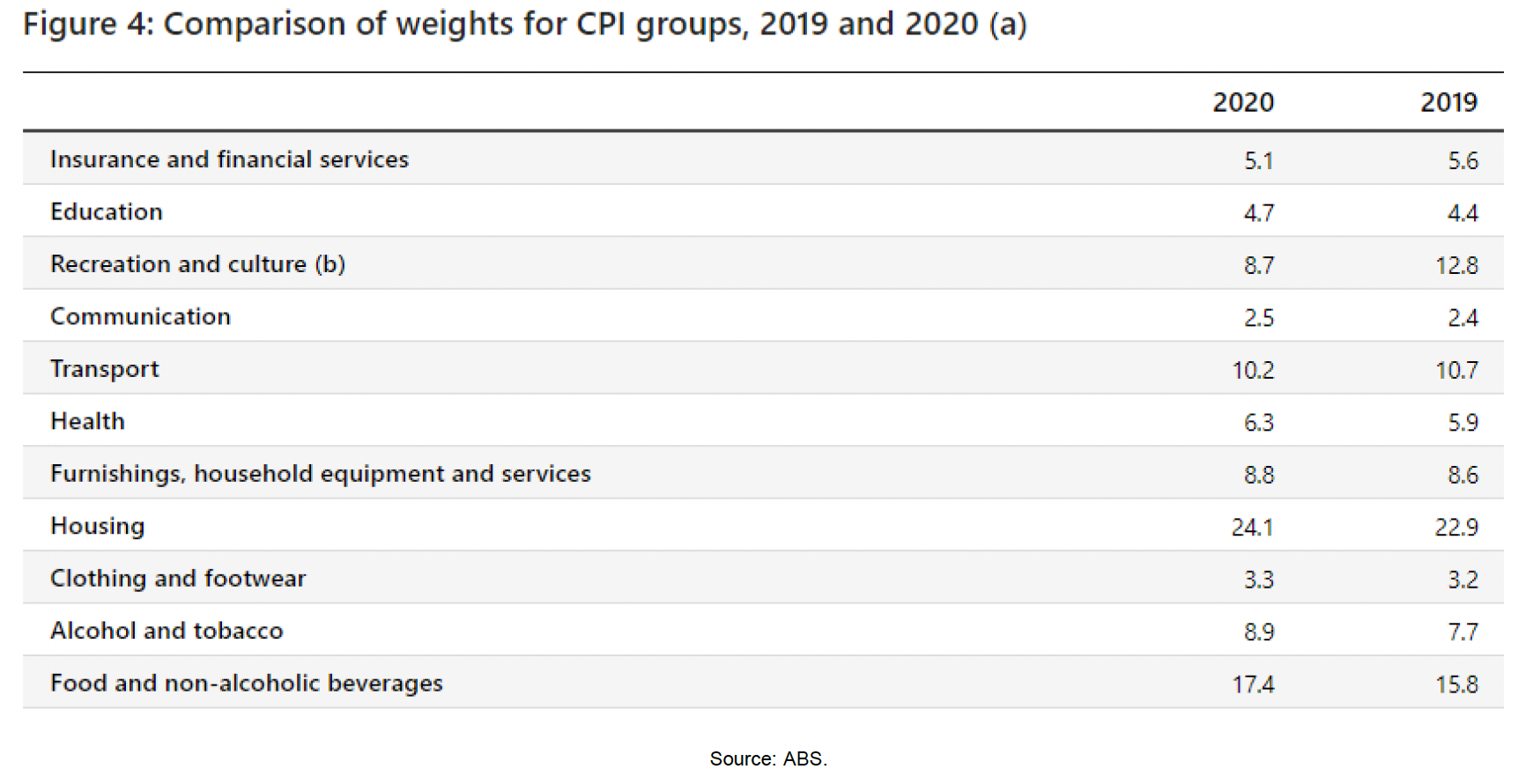

If we look at what makes up CPI in the chart below, it is important to note that food is very large component at roughly 17% of the CPI basket.

Food inflation was relatively subdued at 1.3% YOY in the September quarter. Our concern is that we are seeing all the lead indicators for inflation in goods and services for consumers to be widespread.

You do not have to be too heroic to make the assumption that all these cost pressures through the supply chain will end up with retailers and service providers passing on these cost increases to the end customer.

Supermarkets, for instance, have started to reduce the number and size of promotions. We think that, based on what we have heard from our calls, material price increases will come over Christmas and into the new year.

The second issue is that businesses are struggling to fill positions. We feel that this could become more acute as we head out of lockdown and demand spikes.

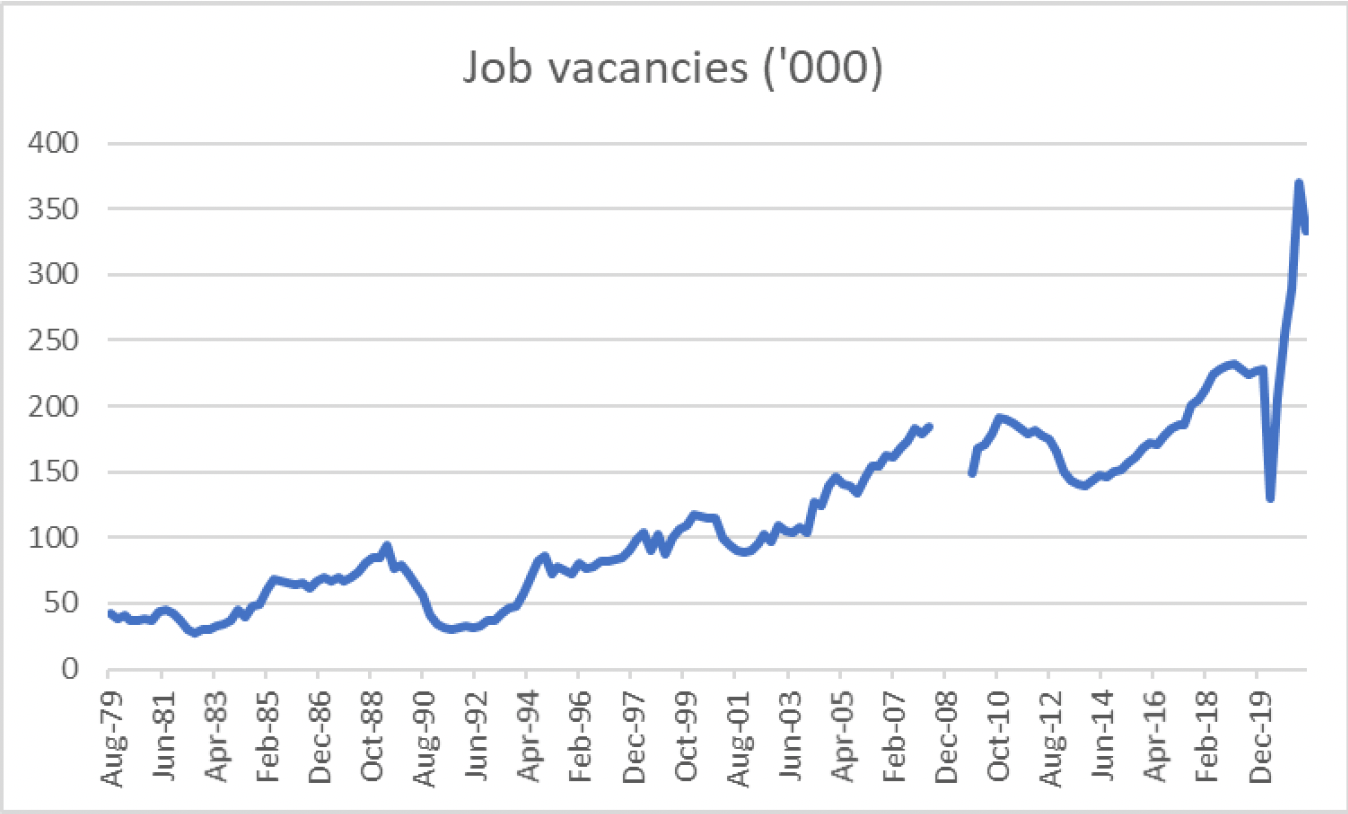

An indicator of this is the increase in job vacancies. As you can see from the chart below, this has spiked during this year.

While it pulled back a little in the last couple of months due to lockdown, we believe that as we come out of lockdown and businesses start to feel more confident, job vacancies will surge through 400k, which is well above historic levels.

Source: ABS.

A similar story could be seen by Seek’s candidate availability index which is making new lows every month.

Source: Seek Employment report.

Two x-factors to consider

It is often said that history doesn’t repeat but it rhymes. If this bout of inflation is more than transitory, it pays to observe what happened in the last period of sustained inflation (late 1960s to early 1980s).

While there are some similarities in the set-up (loose fiscal policy, high levels of speculative behaviour), there are some key differences.

We believe two X-factors which could impact inflation and inflation expectations are the impact of social media and the impact of the transition to green energy.

Back in the 1970s, the internet, let alone social media were not even a thought. We feel that social media has the potential to add fuel to the inflationary fire through its impact on consumer psychology.

It wasn’t that long ago that we saw ridiculous scenes around the world of people fist fighting over toilet paper in supermarkets. The speed at which user-generated information travels to hundreds of millions of the world population in a matter of seconds thanks to social media is scary.

What if these toilet paper wars were a dress rehearsal for the main event? What do we mean by this?

First of all, every time there is an empty shelf of a certain item anywhere in Australia (or the world) it will be known by the majority of the population within hours or maybe even minutes.

Consumers’ reaction to posts of empty shelves may be like the proverbial bank run. What if we start to see broad-based panic buying driven by pictures of empty shelves? Could this exacerbate the supply chain issues?

The second issue which social media could inflame is when supermarkets start putting prices up on everyday items. Wait until people start taking photos of a pack of Corn Flakes being 10% more expensive this week than the previous week.

Back in the 1970s, it may not have been as obvious and, if it was, the speed of information was materially slower. However, anecdotes of increased prices could increasingly populate people’s social media feeds.

The way that inflation can become more endemic is through the psychology of consumers and businesses alike. If consumers start believing that inflation is present, they may buy more today to save paying a higher price in the future.

Therefore, observing and understanding social media’s influence on inflation is going to be important. It is not clear whether its influence will be material, but we think it warrants our observation and analysis.

As if on cue, Jack Dorsey (CEO of Twitter) posted on the weekend: “Hyperinflation is going to change everything. It’s happening.”

It will be interesting to see how this ends.

Over the last six months there seems to have been a tipping point where corporates and countries more generally have got on the front foot and started to lay out plans to move to net zero emissions within a certain timeframe (often around 2050).

Most entities have a 2030 target of reduction and generally have a clear path on how they are going to get there. How is this going to influence inflation? There are two potential impacts.

First of all there is the cost of energy generation. Longer term, with all the capital being invested in renewables and if you believe that technology of battery storage will continuously improve, this shift should be longer-term deflationary.

However, it is the transitional period over the next ten or so years which could end up being problematic. Traditional forms of energy generation have relied on coal and natural gas.

Building a coal mine to supply the seaborne thermal coal is very capital intensive and requires infrastructure (usually rail) to get the coal to the ports.

Therefore, anyone wanting to invest in a project would need to feel confident about the demand for coal over the next decade at least before committing capital.

Given the uncertainty about the future of coal, the lack of financing as banks pull out of the sector and the length of time to get mining licence approvals, there has been very few new coal mines built in the last five years.

The problem here is that renewables cannot replace base load generation, nuclear is still a no-no in a lot of countries and not every country has access to hydro-power.

Therefore, given the lack of capital spent in coal and the fact that it is a depleting asset, this will result in bouts of energy price spiking as we are experiencing now.

Throughout this transitionary phase, we feel that due to the lack of capital spent in gas and coal, we will continue to see volatility (more than likely upside volatility) in energy prices.

Another thing to consider in this de-carbonising world is the amount of capital being spent by corporations to get to their individual goals of net zero emissions.

Take Rio Tinto as one example. In a presentation to the market, the company talked about spending $US7.5bn on decarbonisation between now and 2030.

If one aggregates all the capital expenditure required by companies as they try and reduce emissions through replacement of fleet to electric vehicles, build wind/solar farms, improve energy efficiency of various plant and equipment among other things, we are talking of $100s of billions of dollars of capital spend across the top 100 companies in Australia.

Who is going to pay for this? Will this just be a cost borne by the likes of Rio Tinto? Probably not.

As all the companies in the sector spend a similar amount to de-carbonise, this cost will more than likely find its way to higher prices for the end customer over time.

How do you invest in an inflationary environment?

First of all, we could be wrong. There are some very strong arguments to suggest a lot of the inflationary forces we are seeing at the moment could be transitory and, when things settle down, some of the long-term deflationary forces will return like high levels of debt, ageing demographics and technology.

We need to keep an open mind. However, in the event that we enter a period of sustained elevated levels of inflation, we need to spend our time thinking about our portfolio. There are a few points I would make:

It is commonly believed that equities offer a good inflation hedge. The argument goes that holding cash is dangerous (given that will be worth less in a year’s time from a purchasing power perspective) and given bonds will be sold off, one must hold equities.

Corporations can protect themselves from inflation by putting prices up and generating earnings growth. This theory may have been accurate in past inflationary periods, we don’t believe it is right now. Why?

-

Double whammy – lower earnings and lower multiple

For the first time in well over a decade, we may start to see some wage inflation across the board. While wages growth in isolation is not a bad thing, we feel that it will likely put the current record corporate margins under pressure and result in downgrades to earnings.While some industries will just pass onto the end consumer, more competitive industries may have to wear some of the higher costs. Then there is the multiple.

The ASX 200 All Industrials (ex-banks) FY22 P/E multiple is 28x. We feel that as interest rates increase it is inevitable that the P/E multiple will come under pressure.

This will more than likely have a disproportionate impact on the outliers at the top P/E range 40x and above as long duration stocks (and bonds) tend to get sold off more in a rising interest rate environment.

-

40 years of deflationary pressures and decreasing interest rates

What has worked for the last 40 years may not work for your portfolio going forward. One needs to think laterally about which companies and industries have got a free kick from these dis-inflationary pressures.Almost no money managers have run money through a sustained high inflationary environment, so we are going to have to think on our feet.

The problem is that most indexes are heavily weighted to companies which have been massive beneficiaries of the macro environment over the last 40 years. Therefore, as a whole, the index may not provide the inflation hedge people think it may offer.

-

Passive investing

Passive investing has exacerbated this. Passive money buys whatever is in the index irrespective of its valuation.As a result as a company gets bigger and becomes a bigger part of the index, passive money will buy more of that company, irrespective of valuation and vice versa.

Given the trillions of dollars which has transitioned from active to passive investment over the last decade, this has resulted in a tsunami of money buying companies just because they have gone up and selling companies just because their share prices are lower.

As a result, companies which have had macro headwinds due to disinflation and lowering interest rates have become a smaller and smaller part of the equity indexes, irrespective of their valuation.

The point here is that most indices are market-cap weighted and hence will have a disproportionate weighting towards those companies which have been beneficiaries of deflation.

Therefore, passive investing will provide no protection in an inflationary environment. Having said that, we believe that certain select companies and industries will be good investments.

Back in November 2020 when the announcement of higher-than-expected vaccine efficacy was announced, there was a massive rotation away from what the market deemed growth stocks to value stocks.

At the time, a lot of cyclical companies were trading at deep discounts to mid cycle earnings and hence, as the reflation narrative took hold, they performed very strongly.

This time around is a little different. With indexes up between 30-50%, not a lot is dirt cheap. Rather than reflation from a deflationary shock, we are potentially entering a cost push inflationary environment.

For us, we don’t think one factor is going to work. Some “value” stocks will become value traps as these companies are unable to pass on their higher costs and hence their margins get crunched.

While some of the quality companies will have pricing power to be able to grow their earnings in real terms may also fall as long duration stocks de-rate as interest rates increase. We do not believe that this is going to be as simple as investing in what are perceived as value stocks.

There are going to be winners and losers in every industry in an inflationary environment, though forecasting which companies are going to be the winners is not straightforward.

Some companies with broad-based cost increases will not be able to pass these inflated costs onto their customers. We need to be very careful of investing in these businesses.

On the other side of the coin, some businesses will have pricing power to pass on higher costs but have high margins and some fixed costs. These companies will make for good investments in an inflationary environment.

Identifying this will come down to good old fashioned Porter’s analysis. Some of the areas we are focusing on are:

Strength of customer: We are wary of anyone supplying products to oligopolies like supermarkets in Australia (Woolworths or Coles) or iron ore (BHP or RIO). While strong customers are always trying to squeeze you, trying to pass on your higher costs to customers like Coles and Woolworths is a tough conversation and has the potential to temporarily or permanently negatively impact your margins.

Watch out for strong suppliers: Similar to the above, if you are reliant on one or two strong suppliers for essential goods or services in your business, things could get a little tricky. Take anyone advertising online having to deal with Facebook and Google in an inflationary environment. This increased cost is difficult to make up elsewhere.

What is elasticity of good or service? What is going to be the customers reaction when you put prices up? Is the product necessary? Is there any substitute? With all prices going and real wages likely going to go down, consumers are likely going to become more discerning about value for money.

What are we looking to invest in?

A lot of the attributes listed below are traits we always look for in an investment. However, we feel that they become increasingly important in periods of bouts of inflation.

Buy scarcity: In inflationary environments it is popular to talk about buying hard assets as an inflation protection. What does that actually mean? When people talk about hard assets, they are often referring to property. However, more important for me is to buy scarce assets. If an asset is scarce and is non-discretionary it will generally have strong pricing power which is essential in an inflationary environment. Another area, along these lines, is looking at industries where there has been very little capital invested over the last decade and will benefit from continued strong consumer demand. We like areas where there has been little to no capital investment and new capacity would take a long time to build. Areas like energy, steel, agricultural commodities and most hard commodities fall under this category.

Sustainable cashflow and strong balance sheet: Amazon has been one of the most remarkable investments over the last decade. It had a lot of sceptics given the lack of profitability. However, Amazon has been one of the great success stories as far as value creation is concerned. That being said, there are a heap of companies which want to be the next Amazon and therefore completely disregard the merits of generating sustainable free cashflow. This does not seem to be a motivation for a large percentage of companies out there. As long as there is an element of disruption and a large total addressable market, the earnings are a secondary consideration. The flaw in this business model, however, is the assumption that debt and equity markets will always be on hand to cheaply provide capital whenever it is needed. We feel in an inflationary environment with increasing interest rates and a de-rating stock market, some of these businesses which cannot generate their own free cashflow will really start to struggle. This environment will see the old-fashioned concepts of strong balance sheets and a business model where free cashflow generation is used to sustain the business become increasingly valuable.

Good management: One thing we have learned over the COVID period is just how important a good management team and board is when the macro environment becomes volatile and uncertain. The good management teams were decisive operationally and didn’t fall into the trap of raising equity at the lows. If we move into an inflationary environment, we need management teams to react quickly and adjust to the new macro environment. A properly incentivised management team who understands their industry, can make decisive decisions and capitalise on opportunities will be important in this environment.

Which companies benefit from rising interest rates? In our minds, the companies which were hurt by the potential for interest rates tending to zero should, all things being equal, benefit as interest rate expectations start to increase. Clearly insurance companies and banks with large deposit bases are two types of companies which could be winners in a rising interest rate environment. The headwind from decreasing interest rates should turn into a tailwind as interest rates tick up. Clearly the Australian banks are leveraged to residential mortgages so a Goldilocks scenario is required (i.e. interest rates can go up but not too much).

High margins, low capital intensity: A focus on business models is going to be very important. High fixed (non-CPI indexed) costs should be extremely beneficial in the first few years of inflation. However, over time, low capital-intensive businesses are good businesses to have in an inflationary environment. Eventually capital needs to be replaced and in an inflationary environment, this will eat away at returns. Business models like royalty companies, franchisors or companies which generates a lot of its excess returns through its brand name should all fare very well.

Conclusion

One of the things which we have learnt over the last 18 months is to keep an open mind and not get too confident in the prevailing macro view of the day.

We can see good evidence of lead indicators to a potentially sustained period of high inflation, however there is a lot of uncertainty. Having said that, we think it is important to consider the possibility that the investment conditions of the last four decades may change.

What has worked over the last 40 years (and exacerbated by pro-cyclical passive money in the last decade) may not work going forward. The most obvious investments which will suffer in an increasing interest rate environment are bond proxies, highly geared companies and long-duration investments.

We are not convinced that equities as a whole will offer good inflation protection, nor are we convinced a simple rotation out of growth into value will occur.

In an inflationary environment some companies are going to have their earnings and margins crunched either temporarily or more permanently.

On the long side, we are looking for companies which have pricing power, low elasticity of product, some level of scarcity, a strong balance sheet, good management, some level of fixed cost leverage or benefit from increasing interest rates.

With this in mind, we still own Woolworths and Premier Investments in retail given the high-quality management team, extremely strong balance sheets and we believe both will be beneficiaries of an inflationary environment in their space.

We own National Australia Bank and Suncorp. Again, we feel they are both well capitalised and set to benefit from increasing interest rates and like the management teams. In the commodities space we own Iluka, Oilsearch and Incitec Pivot (among others).

We like the supply side dynamics of a lot of these commodity and energy companies. Not only has there been very little capital spent over the last decade, but also there has been increased consolidation on the supply side. This makes for strong underlying commodity prices with any demand spike.

On the short side we are looking for some COVID winners, which we believe the market has valued materially too high which will fall once the economy starts to normalise.

We are short some companies which the market perceives as being structurally growing tech companies, however we believe they are much lower quality than perceived by the market.

Finally, we are looking to identify businesses which are going to experience material earnings headwinds through cost pressures and an inability to pass these on through pricing power.

We are excited that there is money to be made on both the long and the short sides over the next 12 months.

More information

This note in an excerpt from the Perpetual Share-Plus Long-Short Fund September Quarter Fund Update.

You can learn more about the Perpetual Share-Plus Long-Short Fund by clicking on the fund profile below.

6 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned