The Yips

Who’s on first?

Jon Lester was a star pitcher in American Major League Baseball, one of the best left-handers of his generation. But for years, he couldn’t do one very basic thing: Lester couldn’t throw the ball to first base.

Every time he tried, the ball would sail past or bounce short. To cope, he avoided throwing to first altogether, often letting runners steal at will rather than risk the throw. His issue wasn’t an injury, and it wasn’t fatigue. Instead, it was a mental block born of a loss of confidence: the yips.

Markets — like athletes — can stumble when conviction gives way. Trump’s tariff announcements created uncertainty, and with US valuations stretched, US trade credibility in question, and foreign capital flows at risk, investors' confidence has been shaken.

You can see that uncertainty play out in markets. In early April, the S&P 500 experienced a significant two-day decline of 10.5%, ranking among the steepest since World War II and comparable to the downturns during the 1987 crash, the 2008 financial crisis, and the 2020 COVID shock. Then on April 9, the S&P 500 experienced an intraday swing of over 532 points—the largest point swing in its history.

While US economic policy does have very real implications for markets, these dramatic shifts aren’t just about the fundamentals. They are also the result of hesitation, overcorrection, and doubt.

Volatility and the value of fear

When investors get nervous, the VIX — the so-called “fear index” — rises. It reflects expectations for how volatile the S&P 500 will be over the next 30 days, based on the pricing of near-term options. In essence, it’s a crowd-sourced measure of anxiety — showing how much investors are willing to pay to insure against downside risk. The higher the VIX, the higher the perceived need for protection.

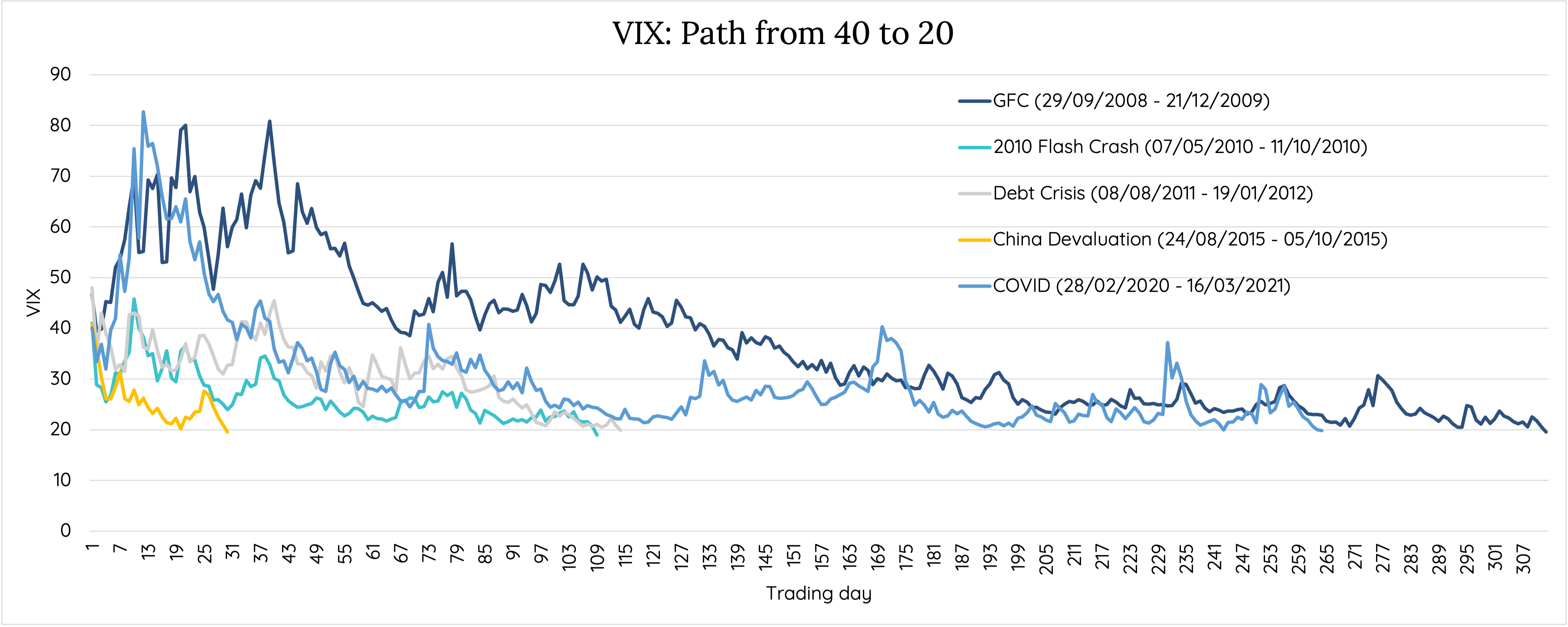

But volatility doesn’t just spike then vanish. As the chart below shows, it tends to stay elevated for months. After COVID, it remained well above normal for about nine months. After the GFC it was elevated for nearly a year.

Number of trading days it took for the VIX to fall back to 20 after spiking above 40.

Source: Talaria, Bloomberg

Reassessing US stability

The kind of uncertainty we’re seeing now is also likely to linger. Businesses don’t have much incentive to respond to the new tariffs by increasing investment. Building factories to produce American-made goods is a major capital commitment — one few firms are willing to make without long-term policy certainty. Tariffs announced one day may be reversed the next, or used as bargaining chips for future trade deals.

The lack of consistent policy direction discourages the type of durable investment that would underpin sustainable economic growth. The result is likely to be a more cautious market — one that reprices risk more aggressively and demands greater compensation for bearing it.

In the near term, businesses have sought to mitigate the risk by stockpiling inventory ahead of tariff increases. This has delayed the full impact on supply chains and consumer prices. However, as these inventories are drawn down, the effects are expected to surface more clearly. Consumers will likely face higher prices and product shortages, while businesses may see reduced demand and shrinking margins. Over time, this pressure could lead to disinvestment, layoffs, and slower economic activity. All this means we’re likely to continue to see market dislocations emerge.

Earning through uncertainty

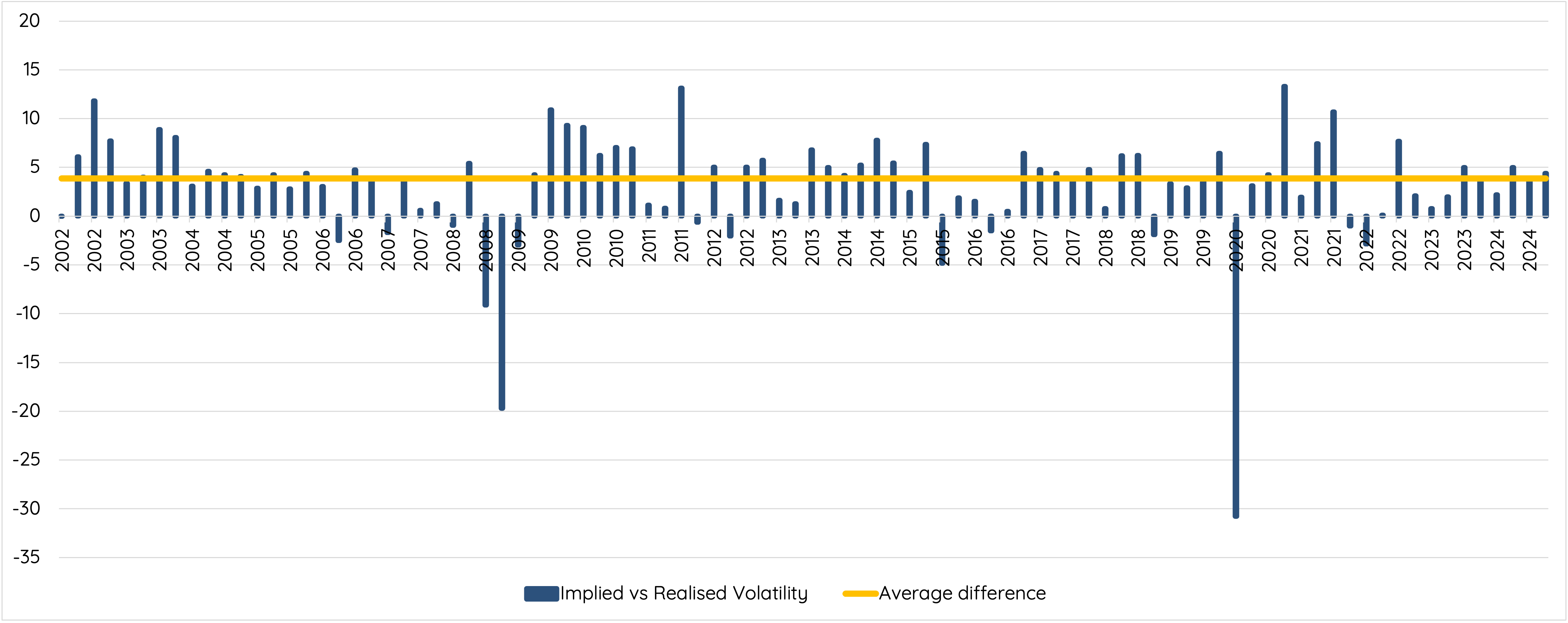

The good news is that these environments can also create opportunities. Periods of heightened volatility mean investors are willing to pay more to take some of the uncertainty away. One way to exploit this is by selling cash-backed put options, where the option seller earns a contracted rate of return for committing to buy a stock at a set price, lower than the current market price. The counterparty pays a premium for that commitment, effectively buying insurance against a fall in the share price. In doing so, they secure the right to sell their stock at the agreed price if the market drops. That premium is usually greater than the actual risk taken, as there is typically a persistent and meaningful gap between implied (expected) volatility and realised volatility.

Source: 90 day volatility, Bloomberg

While heightened periods of volatility create more opportunities to buy at a significant discount to the trading price, it’s crucial that the underlying insurance sold is on securities that are well capitalised, have strong balance sheets and are built to withstand the shocks that can occur to all companies operating in a global economy. Shocks like 2020 and 2008.

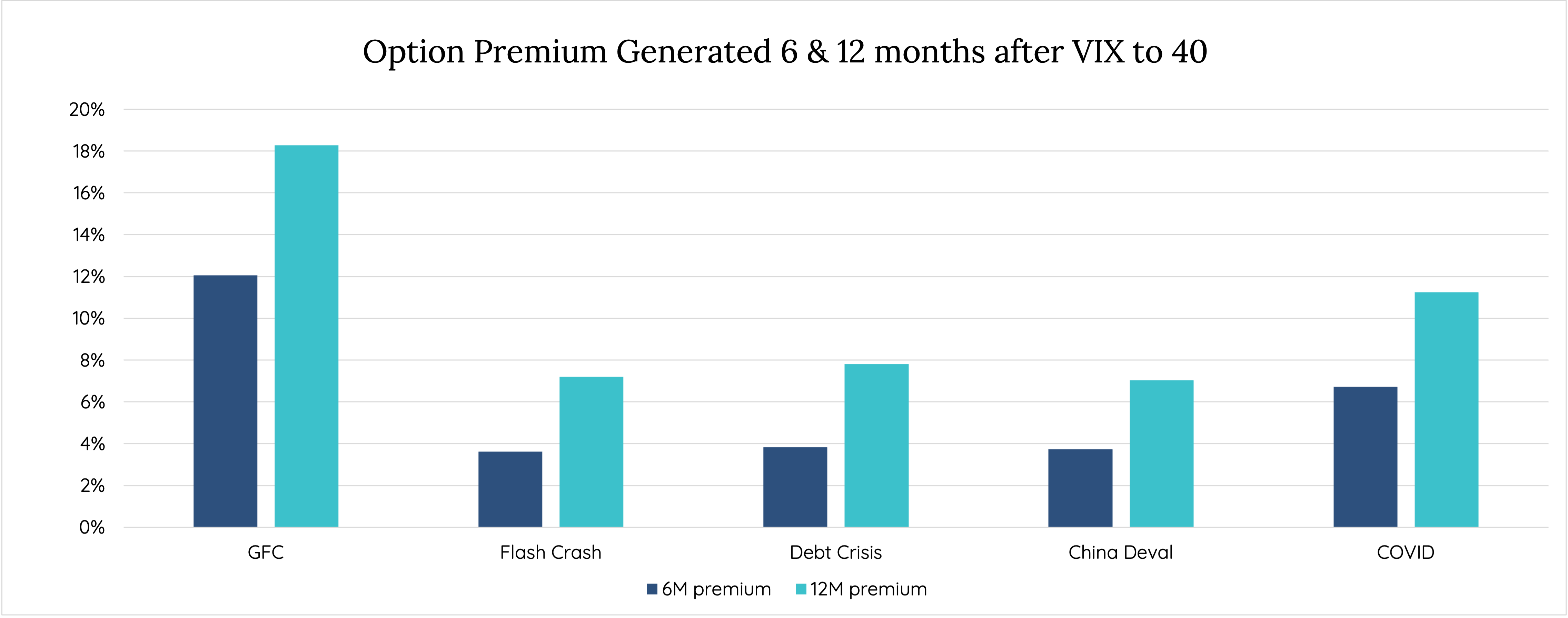

The chart below shows the option premium that can be generated via this process - a process that Talaria uses for every equity we buy - in both the six- and twelve-month periods following major market dislocations — from the Global Financial Crisis to COVID-19.

Option premium generated by the Talaria Global Equity Strategy 6 & 12 months following VIX spike above 40.

Source: Talaria, Bloomberg

The cure for the yips

Jon Lester overcame the yips by adapting his game — using quicker deliveries, altering his pick-off moves, and relying more heavily on his catcher. He focused on what worked, stayed disciplined, and kept performing, even when one part of his game faltered.

Markets are no different. When confidence fades, decision-making can become reactive and unfocused. In those periods, a disciplined process — one that is independent of sentiment, grounded in valuation, and designed to turn volatility into opportunity — becomes essential.

At Talaria, our approach benefits greatly from environments like these. By underwriting risk selectively and ensuring we are compensated for it, we can turn dislocation into an additional source of return and market fear into opportunity. No one can predict the future, but having a consistent and repeatable process that performs in all conditions means you don't have to.

5 topics