Time for a victory lap on inflation?

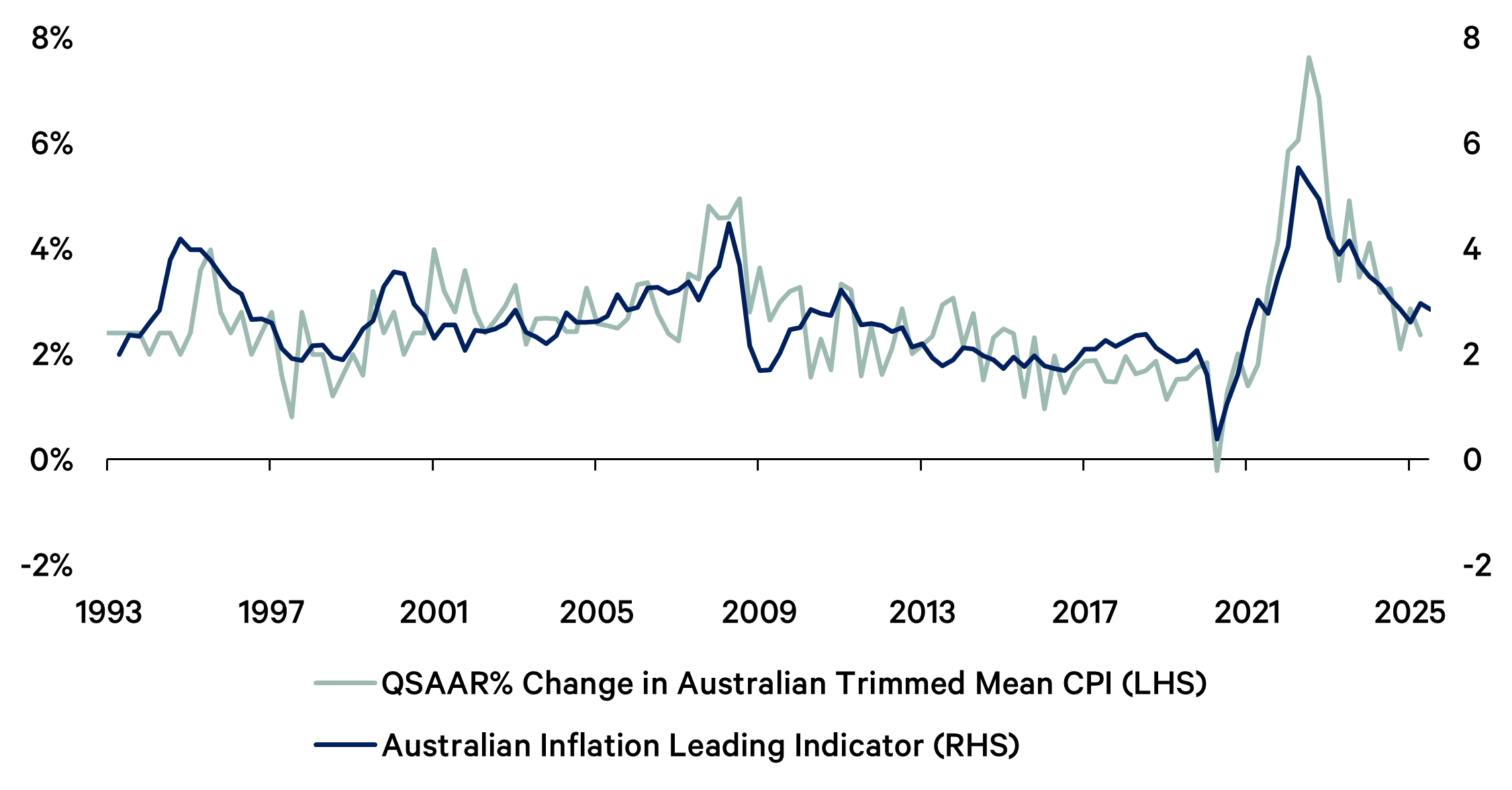

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) preferred measure of consumer price index (CPI) inflation is called “trimmed mean” inflation. This measure uses statistical methods to identify and exclude the most volatile price items from the sample. The rationale is that policy makers prefer to monitor underlying inflation, as it is more indicative of future inflation trends than the often noisy headline figure. Indeed, historical analysis suggests that current trimmed mean inflation is a better predictor of future inflation than current headline inflation.

In the June quarter, Australia’s trimmed mean CPI rose by just 0.6%. This came in below the market consensus of 0.7%, but above the RBA’s forecast from the May Statement on Monetary Policy (SoMP). Bond and money market investors welcomed the result, now pricing in more than a 100% chance of an August rate cut. Markets appear to have looked through the fact that inflation exceeded the RBA’s May forecast, focusing instead on Governor Bullock’s recent comments indicating that the Bank is more concerned with the trajectory of inflation than any single-quarter result.

We see a reasonable case for an August rate cut. However, we do not agree with the market’s aggressive pricing of further cuts beyond August. As such, we are inclined to position for higher Australian short-term bond yields and a flatter yield curve, subject to volatility in global long-term bond yields. Our view is underpinned by several factors.

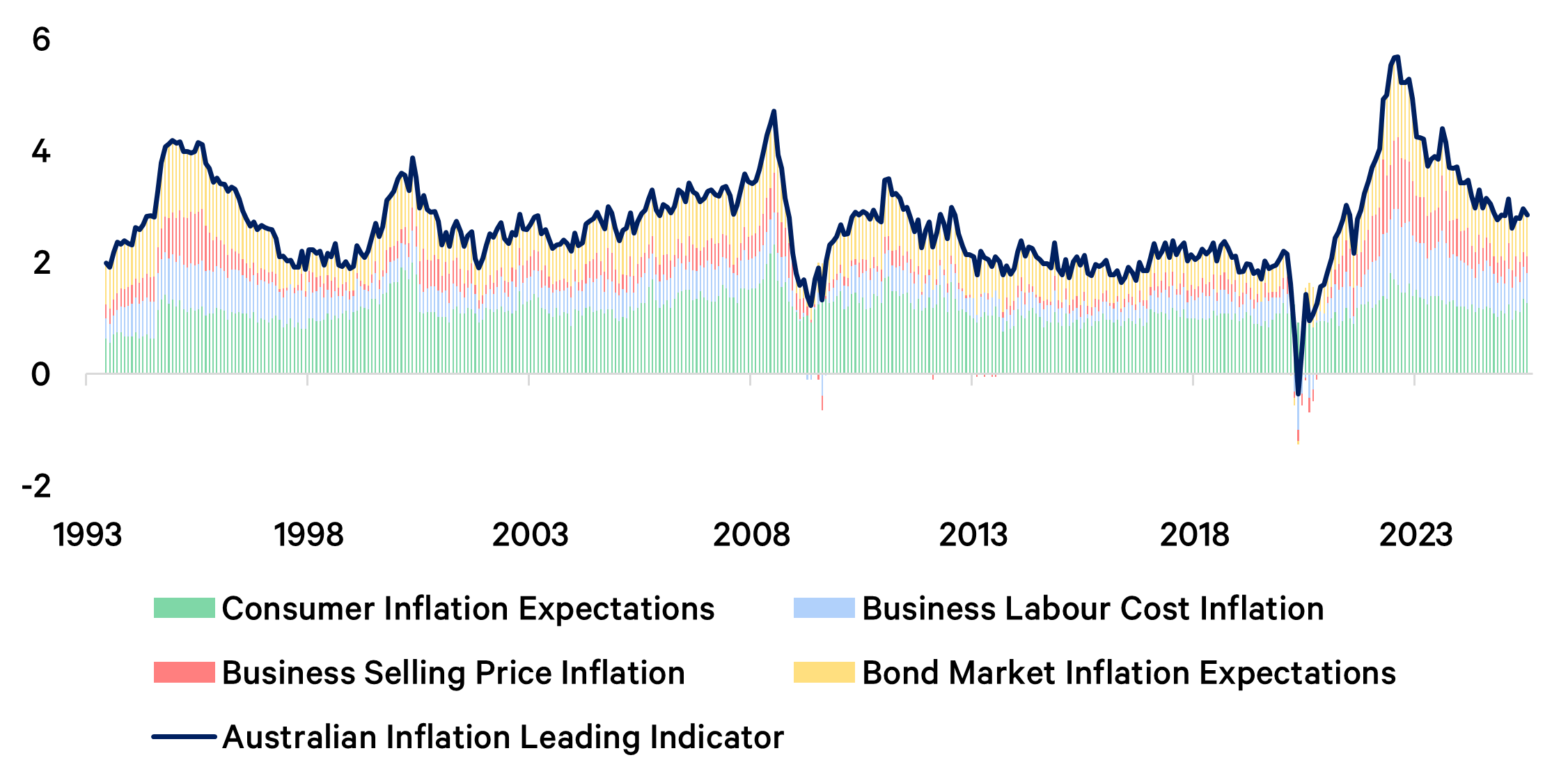

First, leading indicators suggest underlying inflation is running hotter than the June quarter’s trimmed mean CPI implies. While the RBA relies heavily on this measure, we believe even more forward-looking indicators exist on higher frequencies. In the US, for example, the Federal Reserve’s “Common Inflation Expectations” (CIE) index aggregates inflation expectations from consumers, economists and markets. While Australia lacks the same depth of data, we’ve adopted a similar approach using the limited indicators available. Our proprietary Australian inflation leading indicator combines:

- Consumer survey-based inflation expectations

- Reported selling price inflation from business surveys

- Reported labour cost inflation in business surveys

- Short-term bond market breakeven inflation expectation

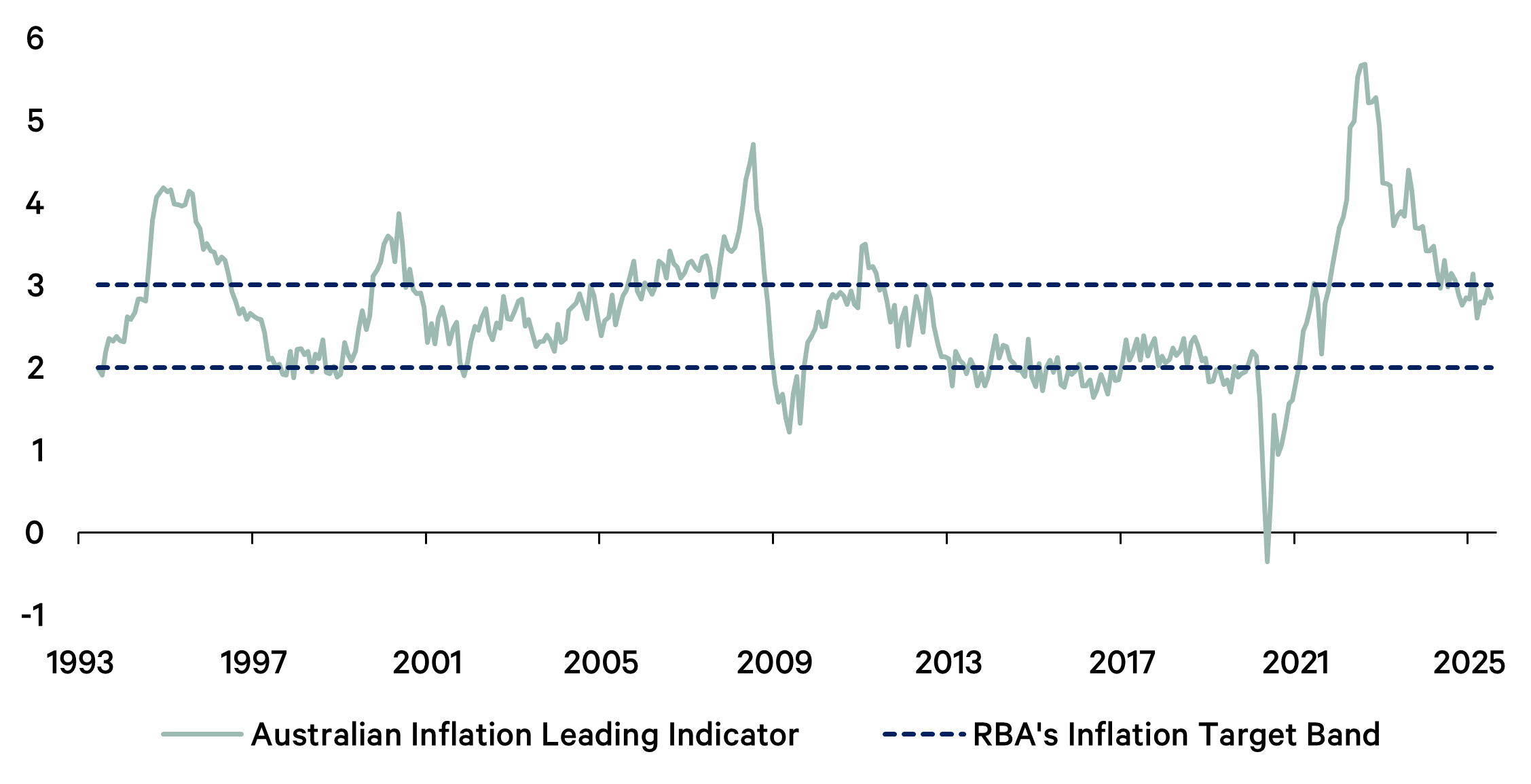

Since the mid-1990s this has served as a reliable leading indicator, or anchor, for trimmed mean CPI inflation. As of July, it points to underlying inflation near the top of the RBA’s 2-3% target band, in contrast to the June quarter’s trimmed mean CPI, which suggests inflation is closer to the mid-point of the band.

US Common Inflation Expectations Index

Australian inflation leading indicator and the RBA's inflation target band

Australian inflation leading indicator components

Australian trimmed mean CPI inflation and inflation leading indicator

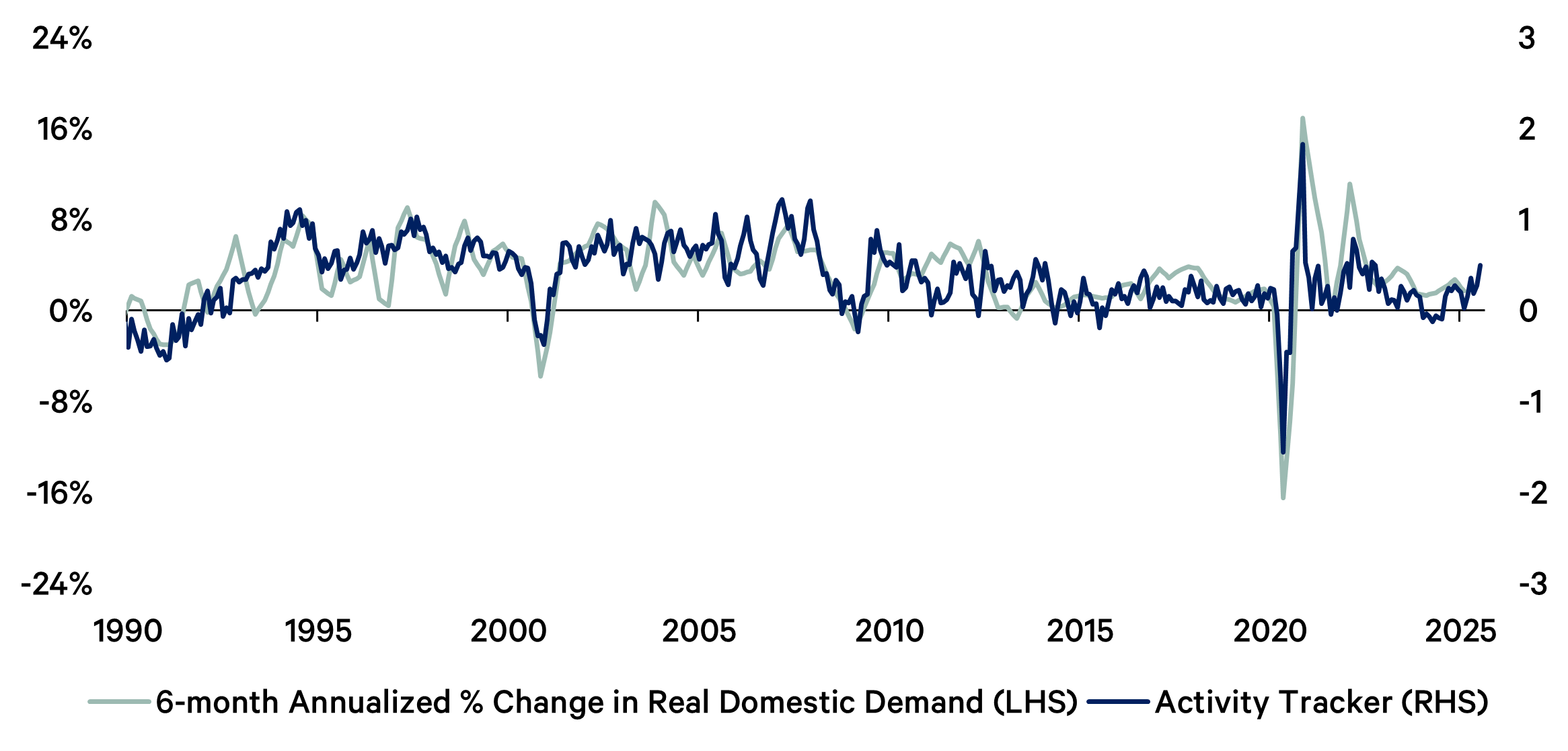

Second, we note recent comments from RBA Deputy Governor Hauser that surprisingly low June quarter inflation is “very welcome” on the one hand, but that the health of the consumer is critically important to the outlook. On the consumer, Hauser acknowledges that spending has been undershooting (improving) fundamentals of late, but suggests that consumption has picked up very recently. Indeed, recently released June retail sales data point to a strong recovery.

When we update our activity tracker for the latest retail sales, credit and building approvals data, we find it is pointing to re-acceleration in domestic demand growth to an above-trend pace. If this “nowcast” materialises, we are looking at capacity in the economy remaining tighter for longer, and inflation remaining sticky towards the top end of the RBA’s target band for an extended period.

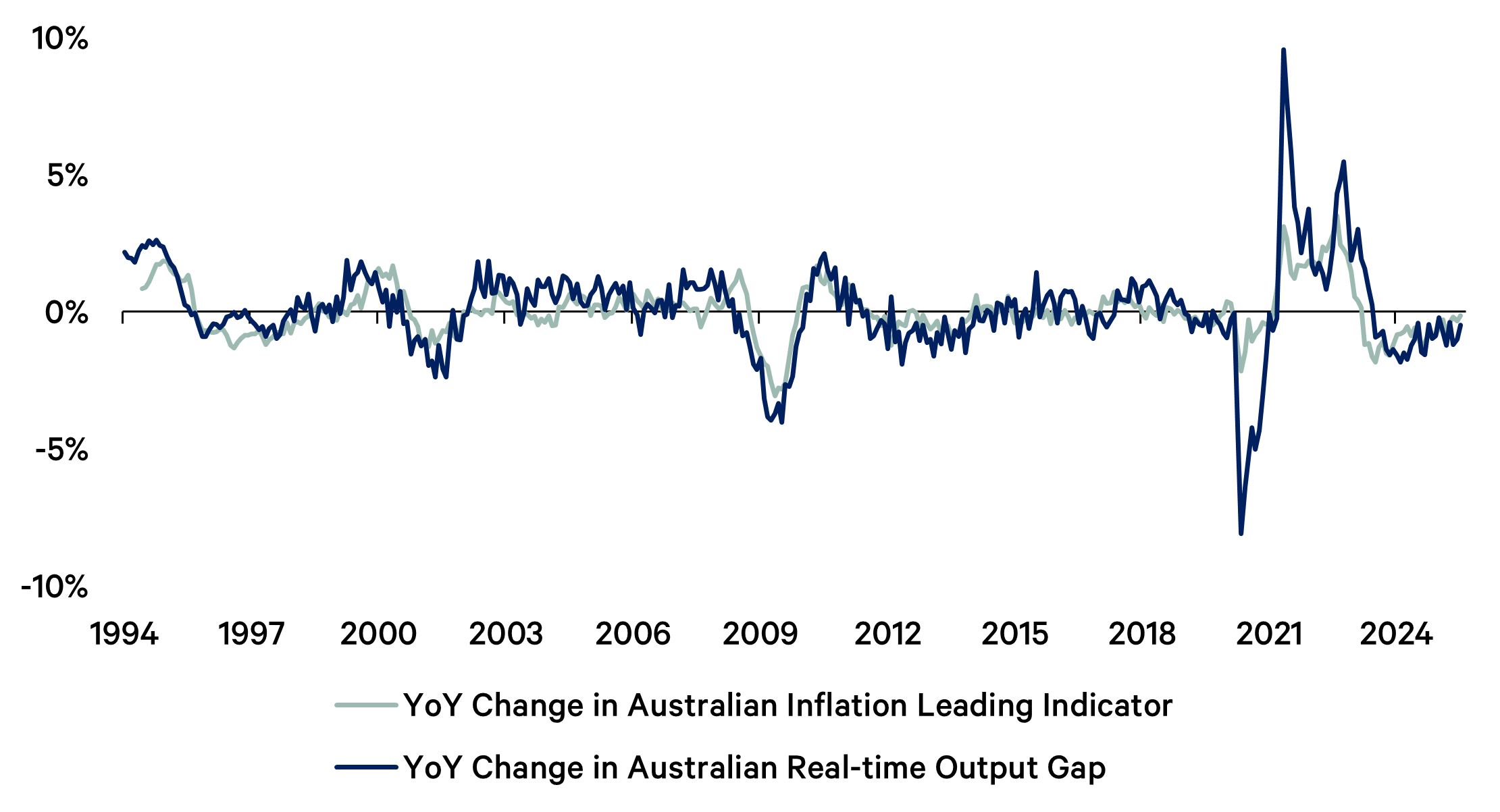

Interestingly, our preferred measure of resource utilisation in the economy, and our inflation leading indicator are flattening out in trend terms, following a period of decline in recent years.

Australian activity tracker and domestic demand

Australian inflation leading indicator and real-time output gap

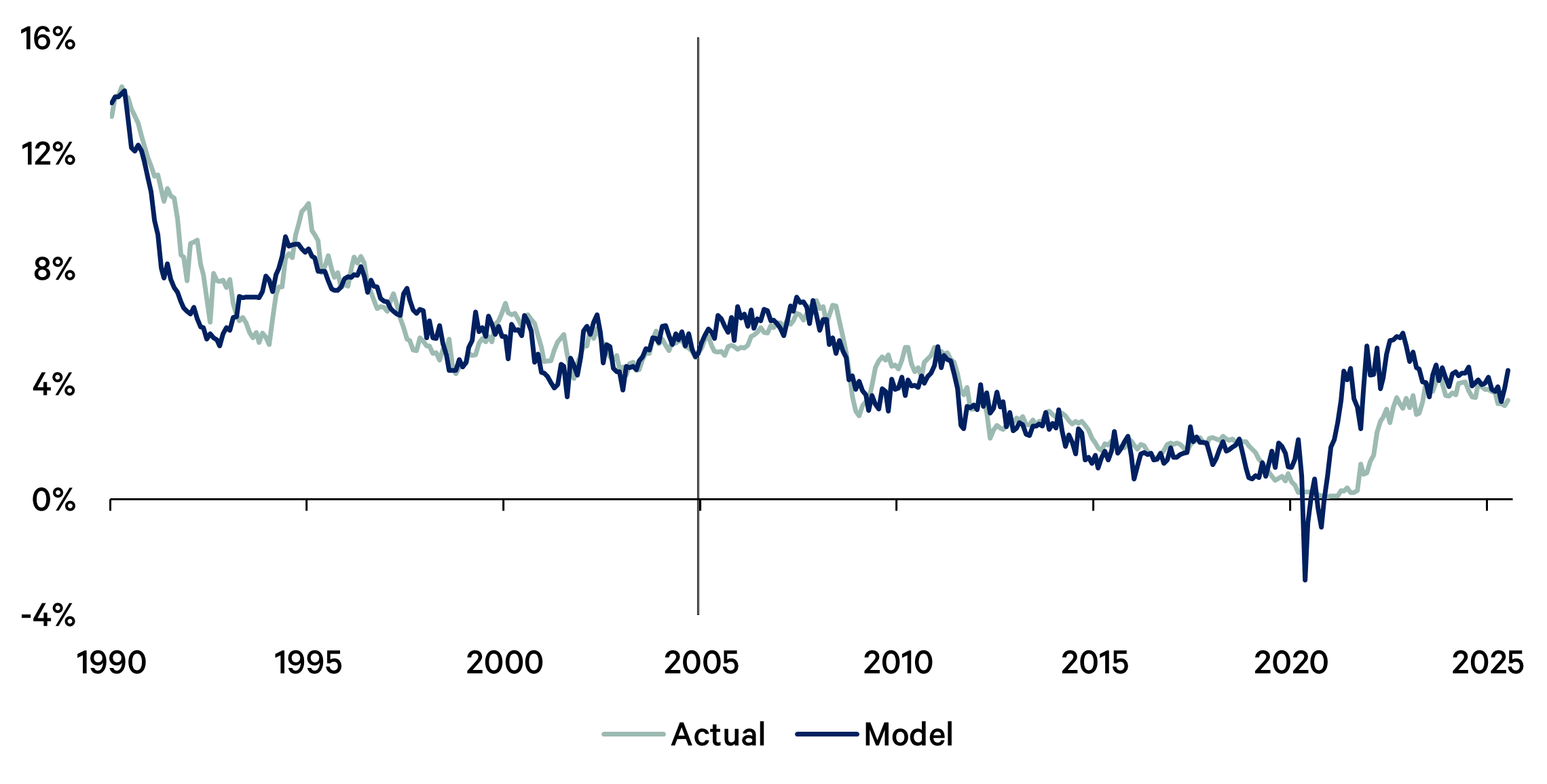

Third, our proprietary model of the three-year government bond yield suggests that yields are too low. Our model is based three core factors:

1. A policy rule for the RBA cash rate based on resource utilisation and the neutral rate;

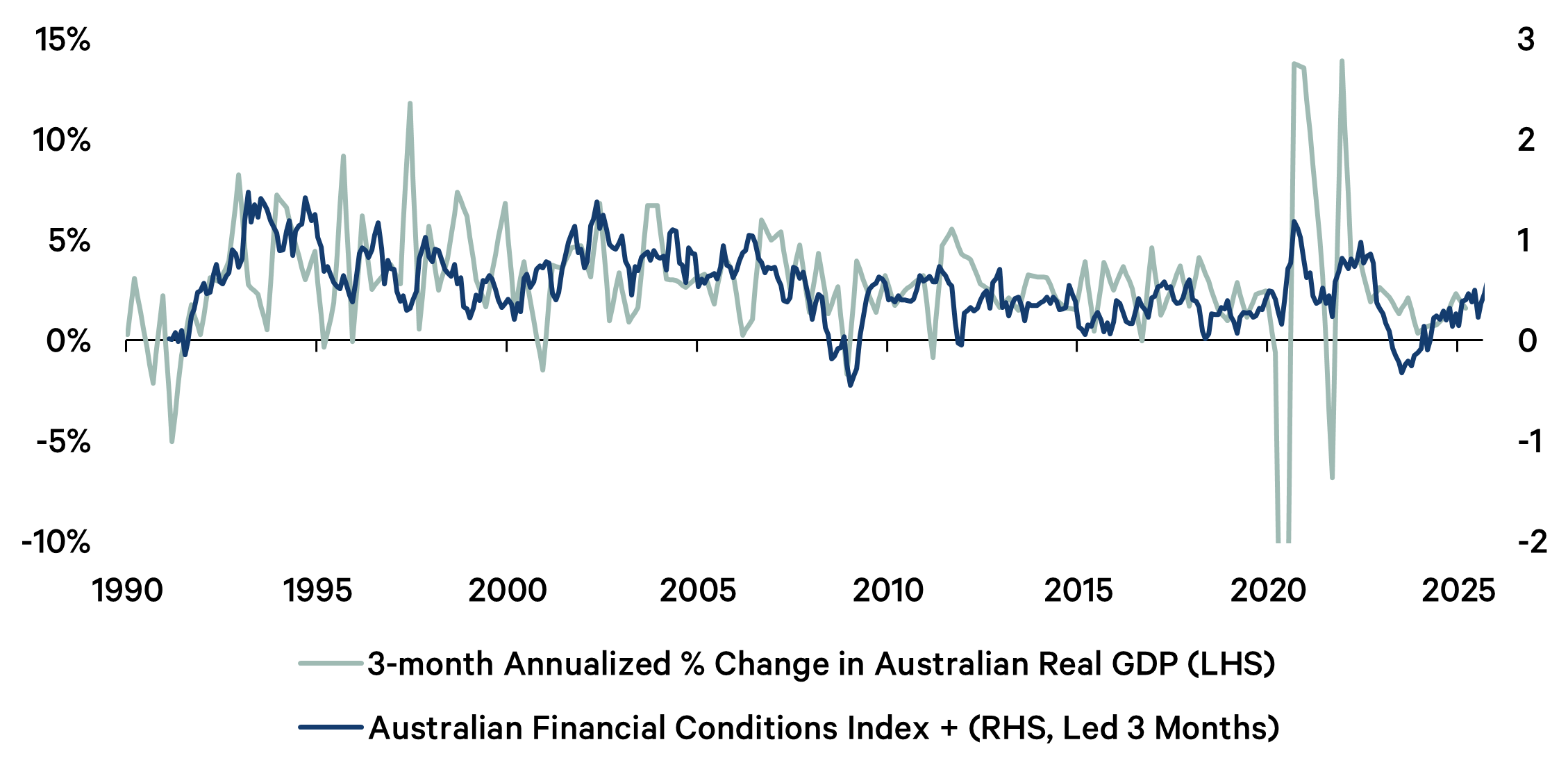

2. A gauge of financial conditions that predicts future activity growth;

3. The degree of co-movement between bonds and equities (given that the research identifies this as a key driver of the short-term bond risk premium).

This model has tracked the fair value of three-year yields quite reliably since 1990, is not overfitted and remains stable enough for out-of-sample forecasting. Currently, it suggests that bond yields are trading at roughly one standard deviation below fair value, a level historically associated with very low total returns in the year ahead.

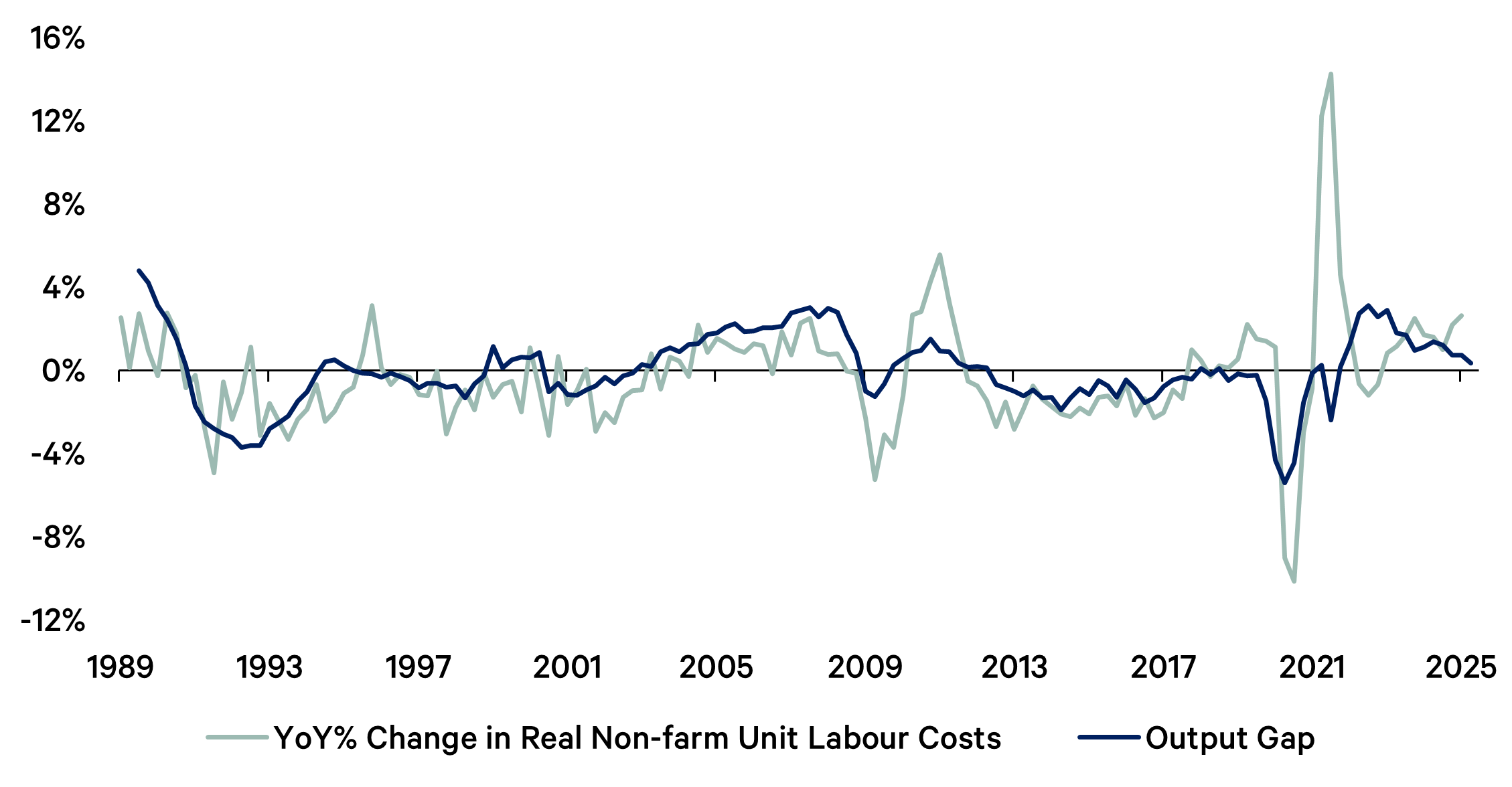

This is partly because resource utilisation is higher than many would think, consistent with rising cost pressures and squeezed profit margins. It is also due to the combination of fading global uncertainty, an undervalued currency, an improving credit impulse and recent rate cuts, which is likely to support a re-acceleration in growth over the next year, adding to capacity constraints and potential inflation pressures.

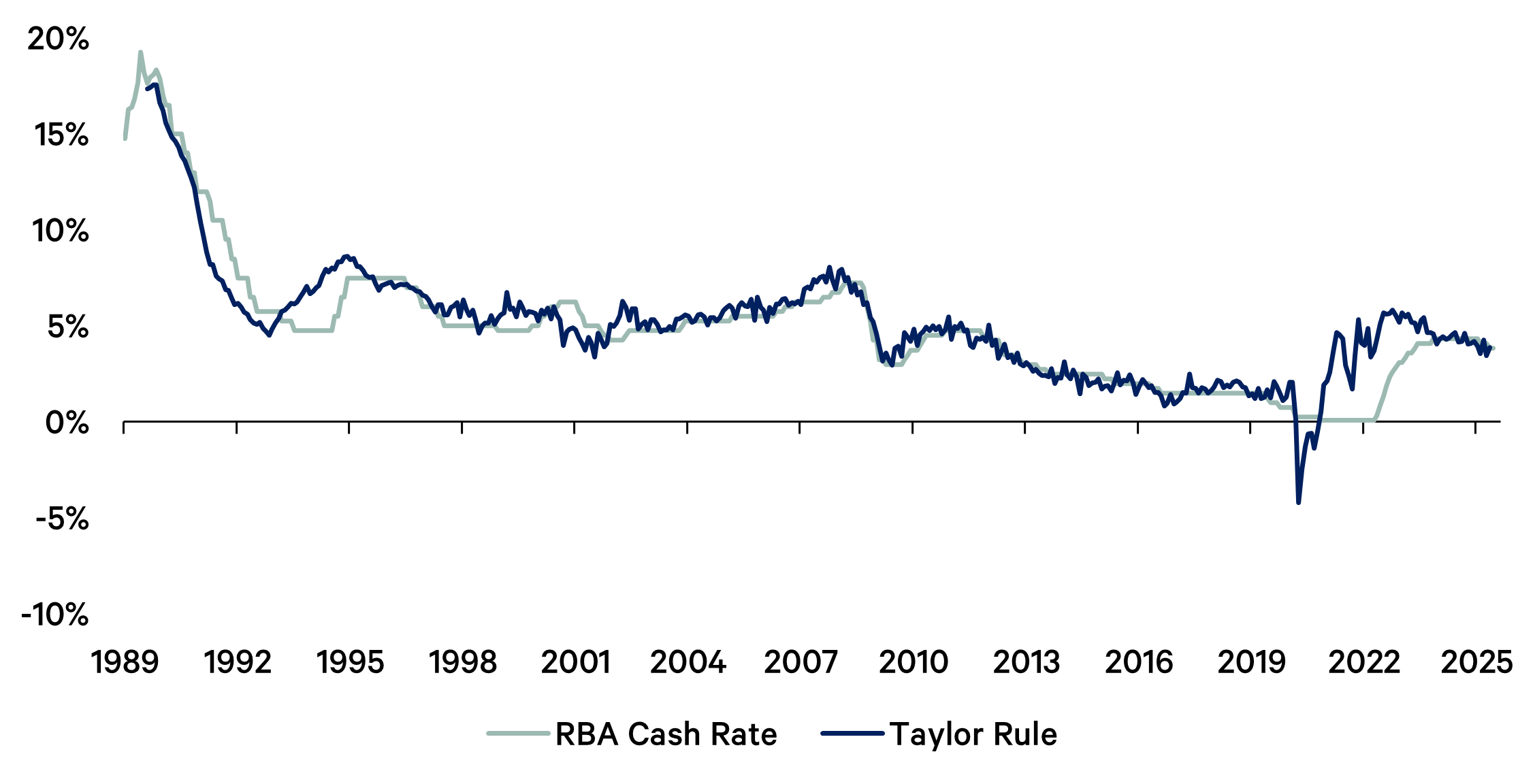

Simply put, our framework indicates that the market is extrapolating recent RBA cash rate cuts too far into the future and could be easily wrong-footed by a more neutral or hawkish stance from officials in upcoming meetings. Even if the RBA cuts in August, the risk is that officials do not endorse currently dovish view of rates embedded in market pricing.

Australian three-year bond yield model

RBA cash rate and “Taylor rule” prescription

Australian real unit labour costs and resource utilisation

Australian real gross domestic product and financial conditions index

5 topics

1 stock mentioned