Unintended Consequences of Government Policy

This last month or so has been a particularly challenging period for a lot of market participants. As a fund manager, volatility spikes can be disconcerting especially after a decade of relatively benign volatility.

What we saw in March was a huge liquidation from hedge funds deleveraging and passive funds/ETFs selling shares to meet redemption requests. In some ways, the market is beginning to feel a little more discerning for the first time in a while. This is a welcome change from most of the last five years where the biggest driver to future share price performance has been share price and earnings momentum.

Throughout this piece, we are not going to use the word “unprecedented” (apart from just then). While a lot of the events are indeed without precedent, we have been reading a lot of reports and that word has been one of the most over-used words. While the specific event is without precedent, we live and invest in a world where the future is always uncertain.

As a value investor we like a margin for error and don’t like paying a massive multiple on earnings as the future can always throw up unexpected challenges. Every time there has been a “crisis” the word “unprecedented” is bandied about to justify previous investment strategies or choices. Whether it be the Asian Crisis, Long Term Capital Management blow-up, Tech Bubble/Crash, September 11, Global Financial Crisis, Euro meltdown or Brexit that same word continues to appear.

We feel that when people start understanding they cannot forecast the next year let alone the next thirty years, these people seriously need to question how they could be valuing companies on nose-bleed P/Es or discounting 20-year DCFs with nicely upward sloping cashflow. Anyway, that is the last time I am going to use the word “unprecedented” (damn I said it again).

So what questions are we trying to answer?

First of all, we are not trying to predict the market movements over the next day, week or month. Markets in the short term are lurching from risk on to risk-off and moving sharply higher or lower depending on the market’s mood of the day and what button the quants decide to press on that day. Predicting or investing based on these movements is a bit of a fool’s game and can distract you from the big picture.

People espousing views that we have reached the bottom and the market is going to continue to rally can be quite convincing as can be those people telling us that the market is going to make new lows. Unfortunately, such comments say more about the people making these predictions than it does about the predictions themselves.

The second thing we are not doing is pretending to be epidemiologists. We are not forming our own models and predictions on infection and death rates from COVID-19. This is already heavily analysed but to summarise, there will be a peak in infections followed by a peak in deaths at some point in the future.

Against this background, here are the three key questions to which we're investing our energy towards figuring out.

1. What are the political motivations?

Given the increased involvement of government within the corporate sector, understanding political motivations is going to be important when trying to predict how this is going to play out across different industries.

The other question everyone seems to be asking is “When will governments allow things to return back to normal?”

Unfortunately, the reality is that things will take a long time to get back to normal. This is just the psychology of human nature more so than any COVID–19 related government policy. No matter how liberal social distancing and isolation policies become, it will take a long time for some people to be comfortable going back on planes or attending concerts, movies, big sporting events or even restaurants.

From the government’s perspective, there is always going to be a trade-off between the health of the economy and saving the lives of our most vulnerable. We do not envy the politicians or regulators in these times. Any decision they make will be criticized as either running the economy into the ground or unnecessarily risking the lives of our most vulnerable. They are humans and are making judgements with the best possible advice where the outcome of their judgements is unknown but will inevitably be heavily scrutinised and criticised by keyboard warriors and the media with the benefit of hindsight.

Things change quickly but as it currently stands, the perception is that the infection rate in Australia is under control and that while the death rate will continue to rise, we are well prepared and seem to have “flattened the curve”. The perception is that due to being on an island and due to early shutdowns and social distancing policy implementation, Australia will come out the other side of this in a much better way than most countries around the globe. This second point is really important.

Given that governments are driven by the election cycle which for state or federal governments is around 3-4 years, government policy tends to err on the side of short-termism as the government of the day is driven by being the most popular at the next election. Success at suppressing the virus is easily measurable in the short term. On the other hand, the full economic harm of policies designed to minimise the spread of the virus could be delayed through fiscal policy at least until after the next election.

Therefore, even if we continue to see news get incrementally more and more positive, both the state and federal politicians are likely to drag their feet a little longer than we all think is necessary to ease these social distancing/isolation rules which are currently in place. We just believe that they are motivated to do so. Therefore, whenever you think we will be allowed to go back to work, go to watch our favourite team or our favourite pub….add a couple of months.

As far as international travel is concerned, we think that needs to be considered differently. If, as is the current perception, Australia comes out the other side of this better than most other countries in the world, then the perception among our voting population will be to fortress Australia. Why should we open our borders to the world and put our population at risk of another outbreak when other countries haven’t been as vigilant?

The world will only be as strong as its weakest link. The point here is that once Australia believes that it has the virus under control domestically, our government is going to be extremely careful about opening up our borders to allow international travelers to come to Australia and quarantining of Australians coming back from overseas will remain vigilant.

The government lockdowns have come at a significant economic and social cost that we do not believe will be overlooked when the government is considering the risks around opening up international travel. Apart from a deal with New Zealand who has been even more vigilant than Australia, we wouldn’t expect international travel to return to normal for well over a year. This will have material impacts on our education and tourism sectors and may slow up our immigration which is a key economic driver.

It’s not all bad for our economy. With the Sydney and Melbourne social butterflies restricted from spending Australian winter in the south of France or Australian summer in Aspen, the two questions are:

- What are they going to post about on Instagram?

- Where are they going to ostentatiously spend their entertainment/travel budget?

One beneficiary could be our local tourism market which is able to cater for domestic travellers.

2. How long will the government keep the economy on life support?

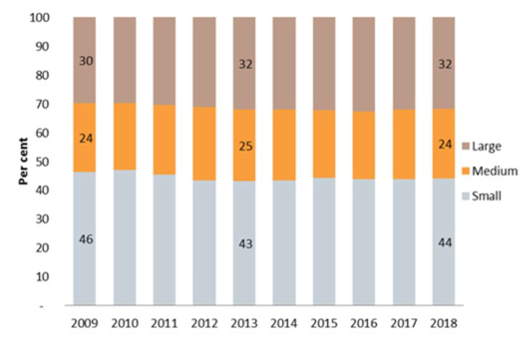

Clearly, any open, capitalist economy where people are forced to stay at home for an extended period is going to be extremely painful for most businesses. This will be felt more in some sectors than others and will be felt most acutely by Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs).

Given SMEs employ around 70% of Australia’s labour force and given the speed at which the economy has been forced to grind to a halt, SMEs around Australia have gone into survival mode. In order to survive SMEs had to do what they could to minimize their two biggest fixed costs: labour and rent. This resulted in a sudden spike in companies firing or standing down their employees.

Chart 1: Composition of private sector employment in Australian by firm size

Source: ABS, Australian Industry, cat. no. 8155, Table 5

Given the massive and sudden spike in unemployment and pending mass insolvency event, the economy needed some resuscitation and got it from the federal government. The centrepiece of the government’s fiscal response is JobKeeper. This is a wage subsidy available to businesses impacted by COVID-19 as measured by the revenue impact and their size. Eligible small businesses (< $1bn turnover) are those which have suffered a 30% or more decline over the last 12 months or for bigger businesses (>$1bn turnover) which have suffered more than 50% decline in revenue. In a nutshell, the government will provide $1500 per fortnight wage subsidy to employers who keep employees on their books. This is a temporary scheme which is scheduled to be turned off on 27th September (six-month scheme).

JobKeeper and eligibility for JobKeeper is the gateway for a lot of other schemes. These include the landlord mandatory code of conduct (discussed later), six-month moratorium on both residential and commercial property evictions and banks principal and interest six-month holiday for households and SMEs under stress. There are plenty of others.

The question we have is just how temporary these plans are and under what circumstances will any government start removing them. Even if one were to be extremely optimistic, and thought that all restrictions were to be removed over the next six months and everything returned to normal, the question is whether or not there would be the longer-lasting psychological impact for both consumers and SMEs of the shutdown of the economy.

Would consumers differentiate between what they want and what they need? Would households and SMEs make sure they save rather than consume?

The point being is that the economy won’t just bounce back even in the best-case scenario. SME’s will likely employ a few less staff and households will squirrel a little more away for a rainy day. In aggregate this will provide a headwind for the economy.

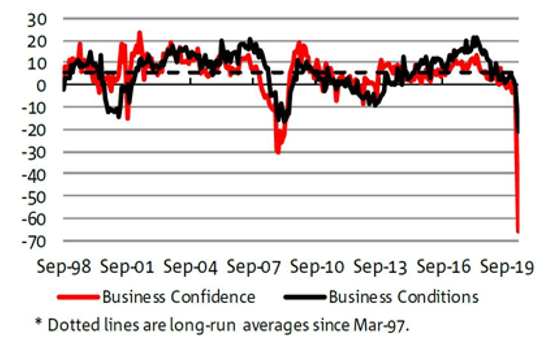

Chart 2: Confidence and conditions hit by Coronavirus

So that brings us back to the question. What happens in six months if the economy is still struggling? I think it is likely 6 months gets extended to 12 months which could get extended again to beyond the next election. Extricating this scheme is going to prove to be tricky. Given the strong fiscal position our government finds itself in and the willingness of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to engage in quantitative easing, the ability to fund this will not be brought into question over the short term.

Where this gets quite difficult is what does the private sector do under these circumstances. We have seen fantastic co-operation from the big end of town with banks, bank regulators, insurance companies and private hospitals doing what they can to help the Australian economy with payment holidays and other unique benefits. However, this cannot last forever.

At what point do banks stop giving a holiday to SMEs and households under financial stress. Remembering that a payment holiday just adds to the principal which will have to be paid off at some point. At what point are landlords allowed to evict non-paying tenants? Will the private sector be able to start making decisions based on what is best for their shareholders when it differs from national interest? What are the unintended consequences of the fiscal/monetary policy?

These are the questions we are asking ourselves and trying to work out in 12 months’ time. What a new normal starts to look like in different industries. We feel that this is more important than trying to guess where the broader market will be next month or the amount of infections next week.

3. What are the unintended consequences of the current policy?

For every action there is a reaction. We are not trying to be critical of the government’s response to COVID-19, however whenever there is heavy-handed government or central bank intervention, there is often an unintended consequence. Take lower interest rates for instance.

The intent from central banks was to make the cost of investment cheaper and be stimulatory, however, it has resulted in households in Australia borrowing more money to buy bigger and better houses and US corporates to lever up to buy back shares. Both these put the economy in the precarious situation it currently finds itself in.

One needs to think laterally when trying to work out the unintended consequences, but this is something we are applying our collective minds to as it may impact the long-term prospects of different companies we are analysing, both positively and negatively.

Delaying a necessary decision can prove costly

While banks providing a payment holiday seems like the right thing to do, given the unique (notice I didn’t say unprecedented) circumstances is it just delaying the inevitable? A payment holiday means someone doesn’t have to pay principal or interest over a six-month period. In another language this is called payment-in-kind which is essentially borrowing more money to pay for your interest. The result is that after the payment holiday you have more debt.

Imagine a scenario that the asset against that debt (your family home or investment property) is worth less in 6-12 months’ time. That would mean you are getting squeezed from both a higher liability and lower asset value. Hence, the decision you are making now, to hold onto your asset and take the payment holiday which is being encouraged by the government may result in financial damage. If the servicer of the loan cannot find a job and is forced to sell the home in 12 months’ time, then this is permanent financial damage.

The point is that the unintended consequence of a payment holiday for both SMEs and households could be a bigger problem down the track. In this example, loan holidays may help a lot of people, but may have unintended consequences of destroying wealth permanently for a heap of others.

Credit Rationing

There is a lot of demand for banks’ credit from their existing customers. SMEs and households are getting payment holidays (which means less amortization of existing debt) and larger corporates are drawing down any credit line they can from their relationship banks. This is all good for the banks’ pre-provision profit and loss statement, but it is extremely capital consumptive for banks.

While the RBA is providing adequate liquidity and the government providing motivation to extend credit to SMEs, there is very little motivation for banks to take on new customers both at the consumer and SME level. We feel that in these uncertain times, there is a decent likelihood that there will be credit rationing for new customers and with non-banks pulling back at the same time. This will provide a headwind for the economy as new business formation will likely be impaired for the short to medium term.

Commercial Property

What is going on in commercial property is extremely interesting. When talking about commercial property I am predominantly talking about retail but is becoming increasingly relevant for office. In the interest of keeping SMEs afloat, the government is looking at addressing the two biggest costs of labour (through JobKeeper) and rent (through Mandatory Code of Conduct). Essentially the government has set up rules for a code of conduct which helps tenants who are suffering due to COVID-19 and have turnover up to $50m.

Essentially, the commercial landlord must take the same revenue hit as the tenant. At least half of this rent is waived completely, and the rest is deferred till later. What is interesting is that the time period for this relief for tenants is for as long as the “JobKeeper programme is operational”.

Given our previous comments about the political difficulty of removing the JobKeeper programme, this rental will more than likely be longer than six months. This is a smart move as it removes one of the two fixed costs facing SMEs in Australia. It is smart politically because there is a perception that commercial landlords are all rich and hence there is very little sympathy from the public.

We feel that in some ways the unintended consequence here could be either substantially higher rents or a permanent impairment of the value of commercial property.

Why? First, there are two attractions about investing in commercial property. The first is stability of cashflows and the second (which is kind of related) is the ability to borrow large sums of money against the asset.

As a landlord, you generally don’t get to participate in the upside when a tenant’s sales are going through the roof, but the flip side is that when a tenant is not going too well you still get paid or you can replace that tenant. Banks liked lending to commercial property because the stability of the cashflows, security of a hard asset and there wasn’t that operating leverage as is the case in most businesses. A precedent has now been now been set.

Commercial landlords now must cop the downside being felt by their tenants. There is even a 6-month moratorium on evictions so this asset which was generating cash and servicing a debt is generating no cash and there is nothing the landlord can do about it. When the dust settles banks are going to want more collateral and hence will likely lower loan-to-value ratios at a time when values could be under pressure. I suspect they will want to reduce their exposure to the sector. Given how important debt finance is for most investors in this space this should negatively impact valuations in the medium term.

The unintended consequences could result in landlords hiking rents to take into consideration the new risk, however, if they are unable to do so it could result in an accelerated downcycle in commercial property valuations which would provide a further headwind for credit providers (a lot of non-banks lend to commercial property) which could lead to further credit rationing.

There are a lot of other unintended consequences of policies being implemented today which is going to impact the long-term prospects of a lot of industries including changes to supply chains from global just-in-time inventory systems to relying more on domestic supply chains.

Immigration may slow to a trickle which will impact economic growth. Could we see the deflationary benefits of globalisation start to reverse? Could we start to see the re-birth of the Australian manufacturing sector? Could we see immigration slow to a trickle which may drive labour inflation in some sectors? We are spending a lot of our time trying to predict some of these unintended consequences and consider how these impact both the companies we invest in and those we are considering.

How we are looking to invest?

It is not all bad news. Interest rates are low for a long time, corporate balance sheets in Australia at the big end of town are generally strong, the Australian government has a strong fiscal position and we live in a great country. There will be a vaccine found and the economy will at some point return to normal.

There are going to be winners and losers. The economic outlook is uncertain, but due to liquidity concerns and wholesale panic, we are seeing some great investment opportunities on the long side through either providing liquidity in recapitalisations or stocks being indiscriminately sold due to mass deleveraging by hedge funds and forced selling from passive funds.

We are not macro experts and so are not going to make investment decisions based purely on where we think the market is going next week. However, every bottom-up stock picker must take into consideration any permanent changes to a specific industry or sector.

What are we looking for on the long side?

- Strong Balance Sheets: In a world where most corporates are desperately trying to shore up their liquidity, having a strong balance sheet is even more of a premium. Not only does this allow companies to be able to survive on materially depressed revenue numbers and cash flow for an extended period, but also to take advantage of opportunities through internal investment or inorganic acquisitions during a cyclical downturn. We feel that strong balance sheets are a premium asset in this environment.

- Good Management: Making a judgement of what makes a good management is a subjective call. However, we tend to like strong management teams who are properly incentivized. Good management to us is different for different companies, but the CEO needs to be able to hire and motivate top notch talent, be able to take risks without betting the farm and has agility of mind and ability to think laterally during a time of crisis. While we like management teams who can articulate their strategy, we shy away from big talking CEOs who are incapable of telling any bad news to stakeholders. This is a lot to ask, we do tend to gravitate towards companies which are agent/principle companies. Where the major shareholder and founder is either CEO or is influential to some degree. Examples of this are Premier Investments, Seven Group, Bingo Industries, Adelaide Brighton or Harvey Norman.

- Market Leadership: Generally speaking, during an economic downturn, the market leader in a certain industry tends to grab a larger market share. This is not always the case, but generally speaking given their access to capital and ability to operate with much lower revenue for longer periods of time. Any demand shock in any industry is followed by intense competition as industry participants try and stay alive, however, over the longer term it is the companies which are the most agile, lowest cost but also the most access to capital which will do the better at the other end of the cycle.

-

Businesses uncorrelated to the cycle - Given the uncertainty about where our economy is going to be in a year or two years, you want to look for businesses which are less sensitive to the business cycle. My personal perspective is that households and businesses are going to differentiate between what they want and what they need. Therefore, investing in companies which provide a non-discretionary product or service is a good start. Some of the more obvious non-discretionary names like Woolworths and Coles have performed well over the last month or so and hence the attractiveness of their non-discretionary nature is well priced into the stock. We like to look for businesses and industries which are less obvious.

With most food being proven to be non-discretionary and the likelihood of economic nationalism, the demand for agricultural products is likely to remain strong. We own Bega Cheese (ASX:BGA), Costa Group (ASX:CGC), Graincorp (ASX:GNC) and Incitec Pivot (ASX:IPL) in this space. Another area we like is the litigation funding sector. As a sector, there is a little bit of counter-cyclicality to it for a few reasons. Omni Bridgeway (ASX:OBL) (the old IMF) through good management and bit of good luck has come into this in an extremely strong position. It has free cash on its balance sheet (not including receivables) of $214m.

Conclusion

One could construct very convincing bull and bear arguments for the overall market. On the bull side there is a lot of panic which is typically a time to start nibbling if nothing else. Most of the noise from fund managers in the press is about how much cash they are sitting on (historically a very bullish indicator). The market seems to have stopped reacting to negative news and the peak in COVID–19 infections will come and go at some point. Add to that the speed and scale of the monetary and fiscal responses on a global scale seems to have staved off any liquidity and financial crisis for the time being.

On the bearish side, this is having a detrimental impact to anyone running a business or employed in the real world (i.e. outside the finance industry). Markets globally from equities to credit to private equity entered this crisis with extremely stretched valuations making them vulnerable to shocks.

Finally, Australia’s Achilles heel is household debt which due to low interest rates and a 28-year bull run in house prices is at extremely elevated levels. If this liquidity event turns into an insolvency event and a proper housing cycle than we are in for a deep recession in Australia. Unfortunately, the bear arguments sound more convincing. The good news is that bears always sound smarter but are usually wrong.

Make the most of market inefficiencies

The Perpetual Share-Plus Long-Short Fund invests in companies we believe will rise in value and takes short positions in companies we believe will fall in value. Stay up to date with our latest insights by hitting the follow button below.

4 topics

5 stocks mentioned