We need to talk about Japan

Japan has been in the news a lot lately. The US announced a trade deal with Japan last week, which essentially settles the tariff for Japanese goods exports to the US at 15%. The big deal here, and indeed with a lot of the US trade negotiations, is autos. In 2024 Toyota (NASDAQ: TM) and Honda (NASDAQ: HMC) featured in the top five selling US passenger vehicles.

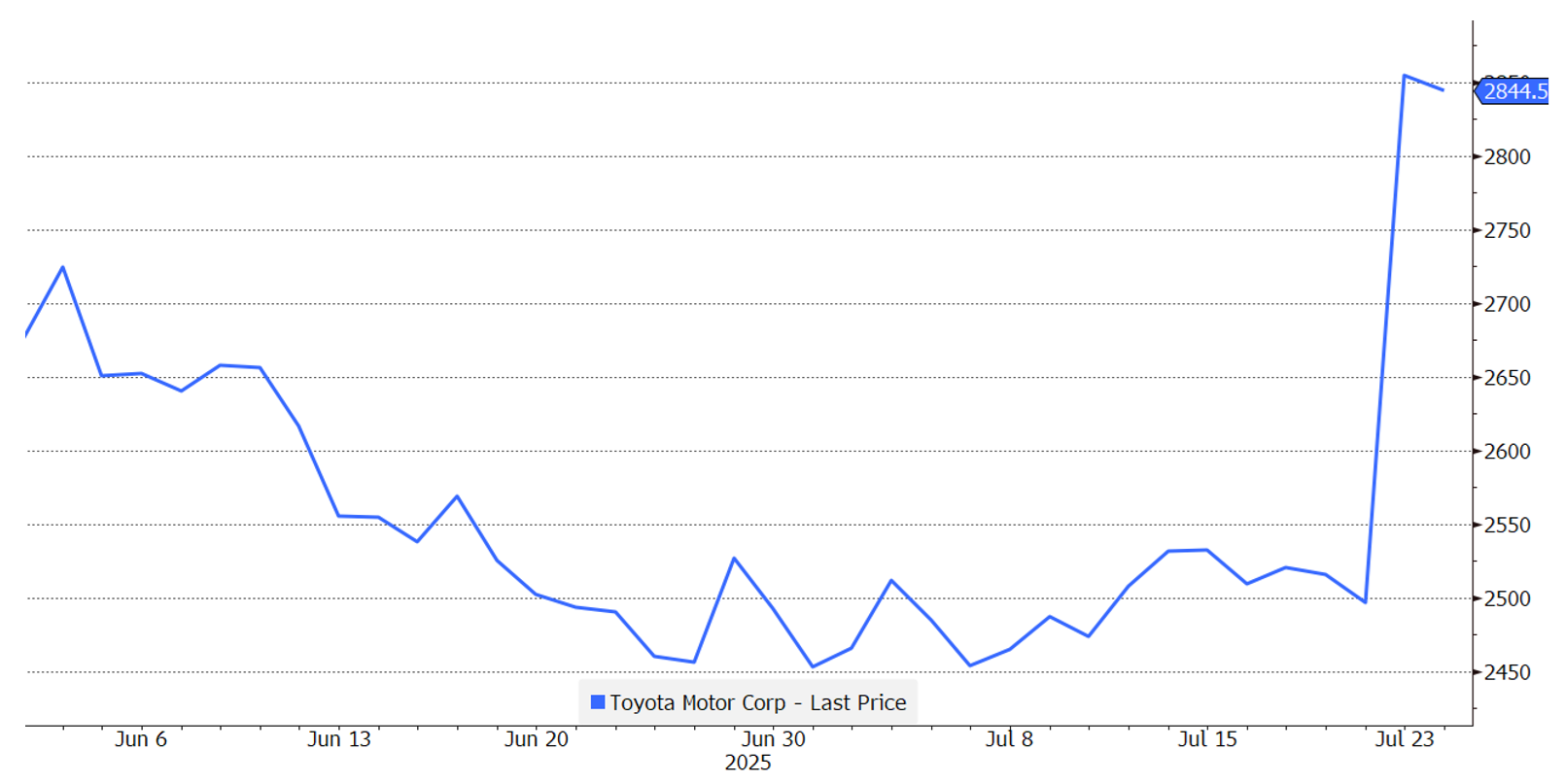

Toyota stock after the announcement:

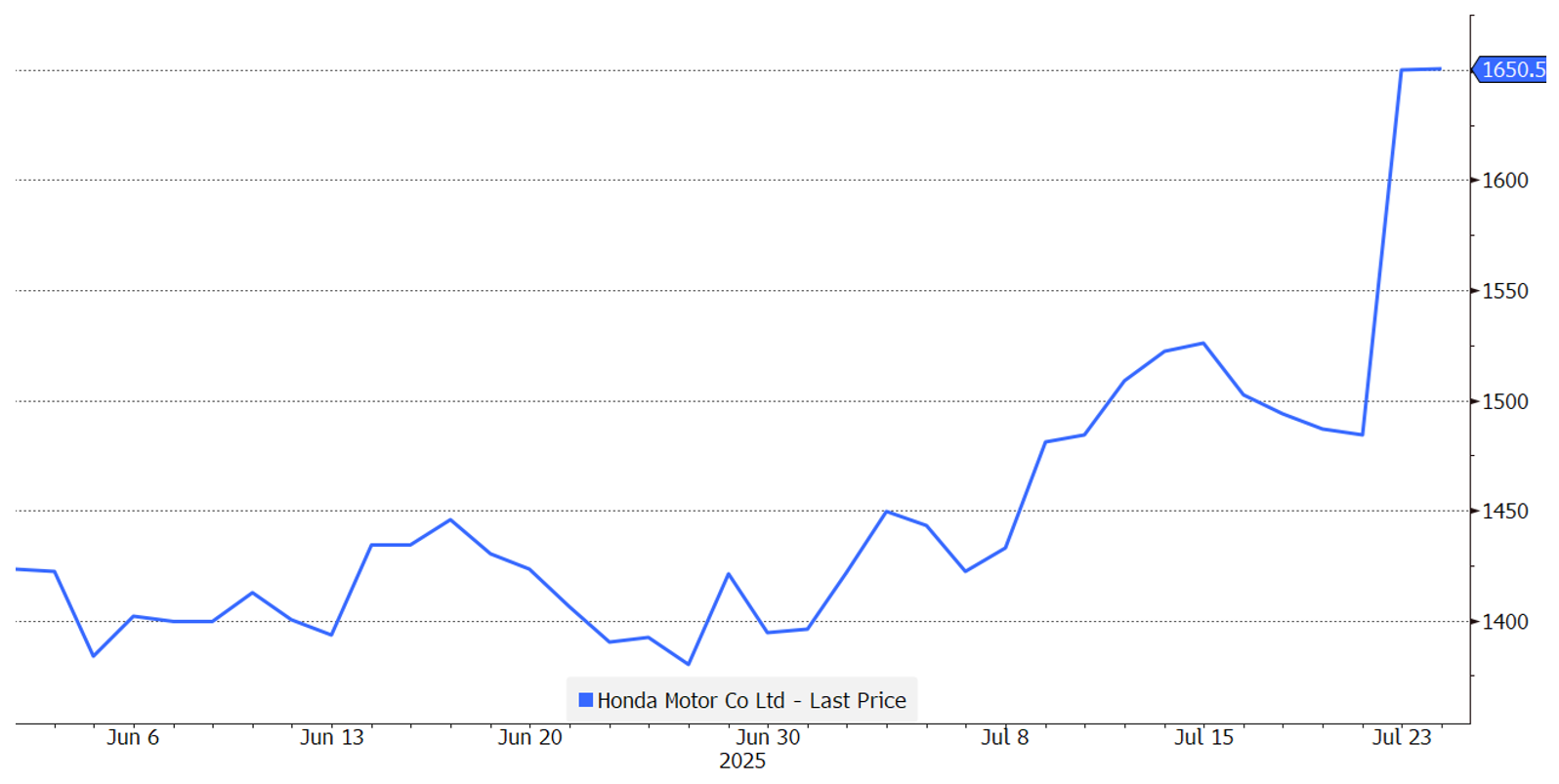

Honda stock after the announcement:

Japan is a big deal for global bond and equity markets. It is one of the largest savings nations in the world. After the property market imploded in 1990, Japan entered a multi-decade period of deleveraging, savings and heightened risk aversion. The bursting of a debt-financed property bubble saw the nation become a massive saver, providing huge amounts of capital to global markets. In an effort to try and stimulate domestic borrowing, the Bank of Japan made money ever cheaper, to the point of negative interest rates and quantitative easing. This didn’t work, and as per leading Japan economist Richard Koo’s term*, a ‘balance sheet recession’ ensued whereby no-one wanted to borrow and you can’t make money cheap enough when there is no propensity to borrow.

The government accordingly stepped in to try and fill the gap, effectively becoming the defacto borrower for Japan, running massive fiscal deficits and then cycling that money into the economy to try and break the doom loop. That all worked fine, as with money so cheap, the fiscal spigots could remain fully open and no-one particularly cared that government debt/GDP ballooned. Until now.

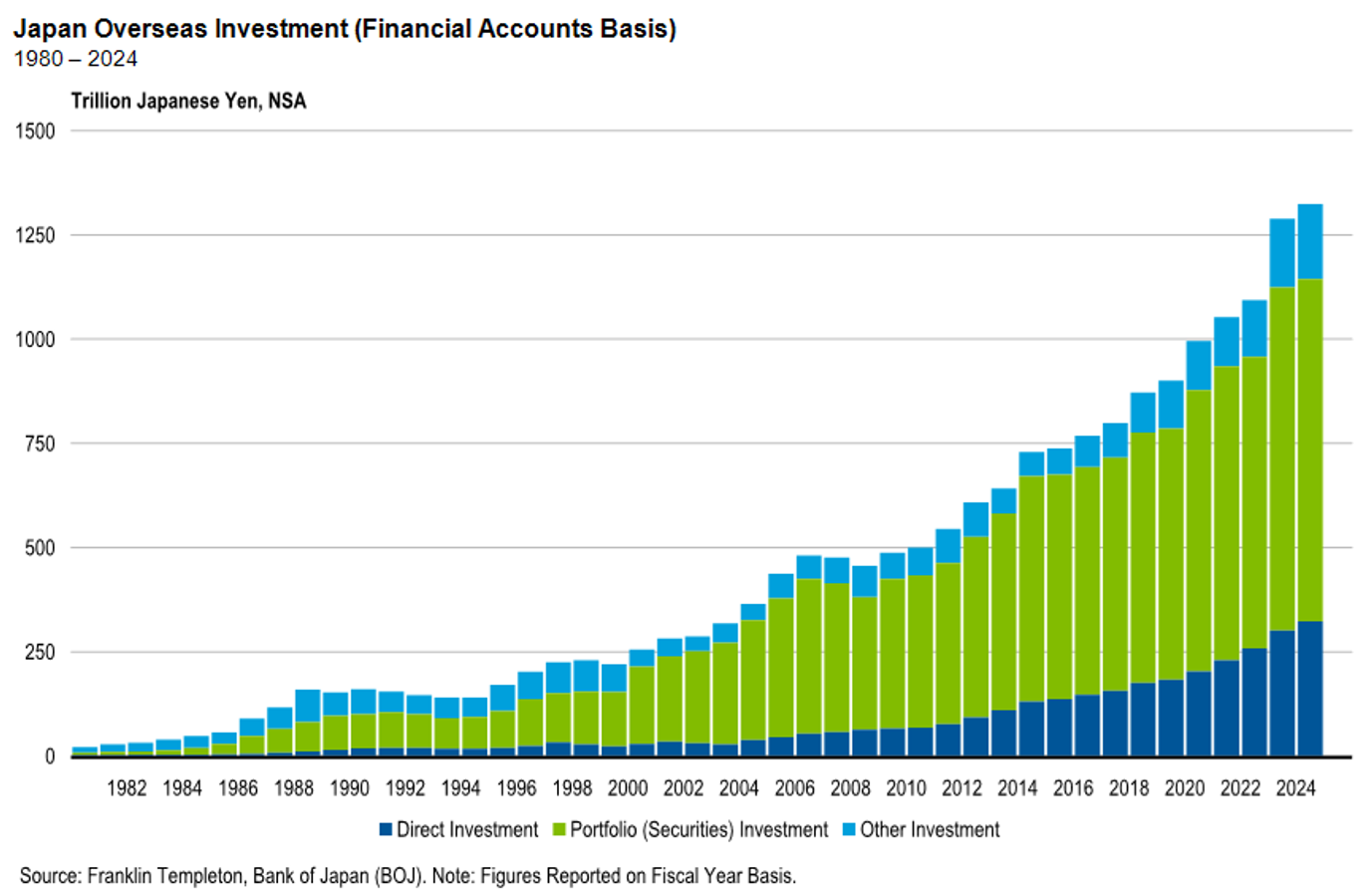

My colleague Josh has been an avid student of Japan and points out that foreign investment by Japanese individuals and institutions is around 1,300 trillion Yen (or ~USD 8.7 trillion). Most of this is in public securities (stocks and bonds) and the bond component of this is centred in USD.

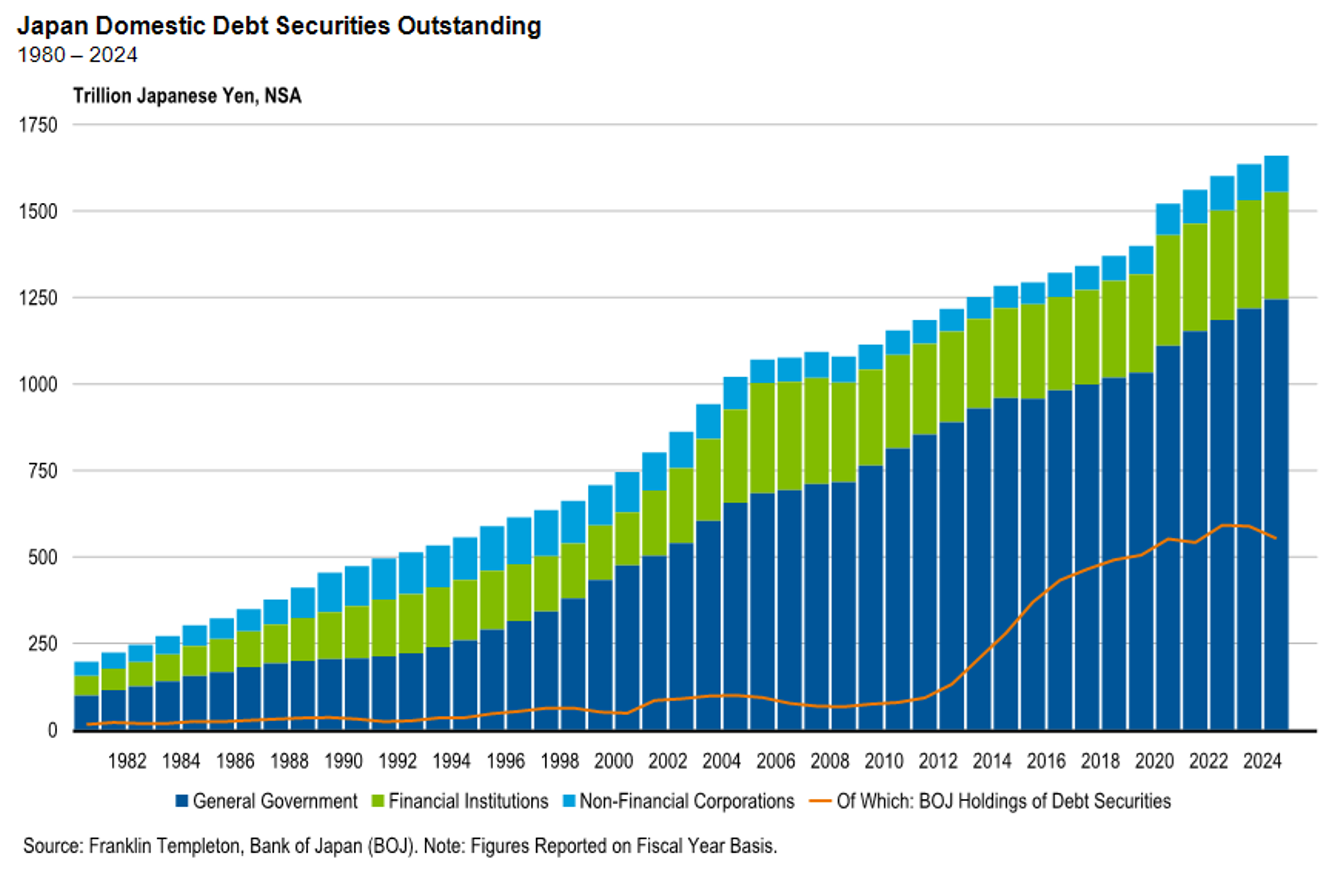

Meanwhile, after a multi-decade period where no one domestically wanted to borrow and invest except the government, the domestic market is not surprisingly massively swamped by Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) with the Bank of Japan (BoJ) the dominant player. The orange line below shows the BoJ ownership of JGB’s.

The huge imbalances between Japan’s fiscal deficit and the private sector’s surplus of savings being directed offshore has been the subject of concern for years. Many have speculated that Japan’s government bond market would collapse given the gargantuan deficit, only to be disappointed as the money printing machine at the BoJ has capped yields effectively. But the story can’t go on forever. For the first time in decades, inflation is back in Japan - as it is everywhere. And with it, higher yields. The 30-year Japanese Government Bond recently moved above 3% and the highest in more than 25 years.

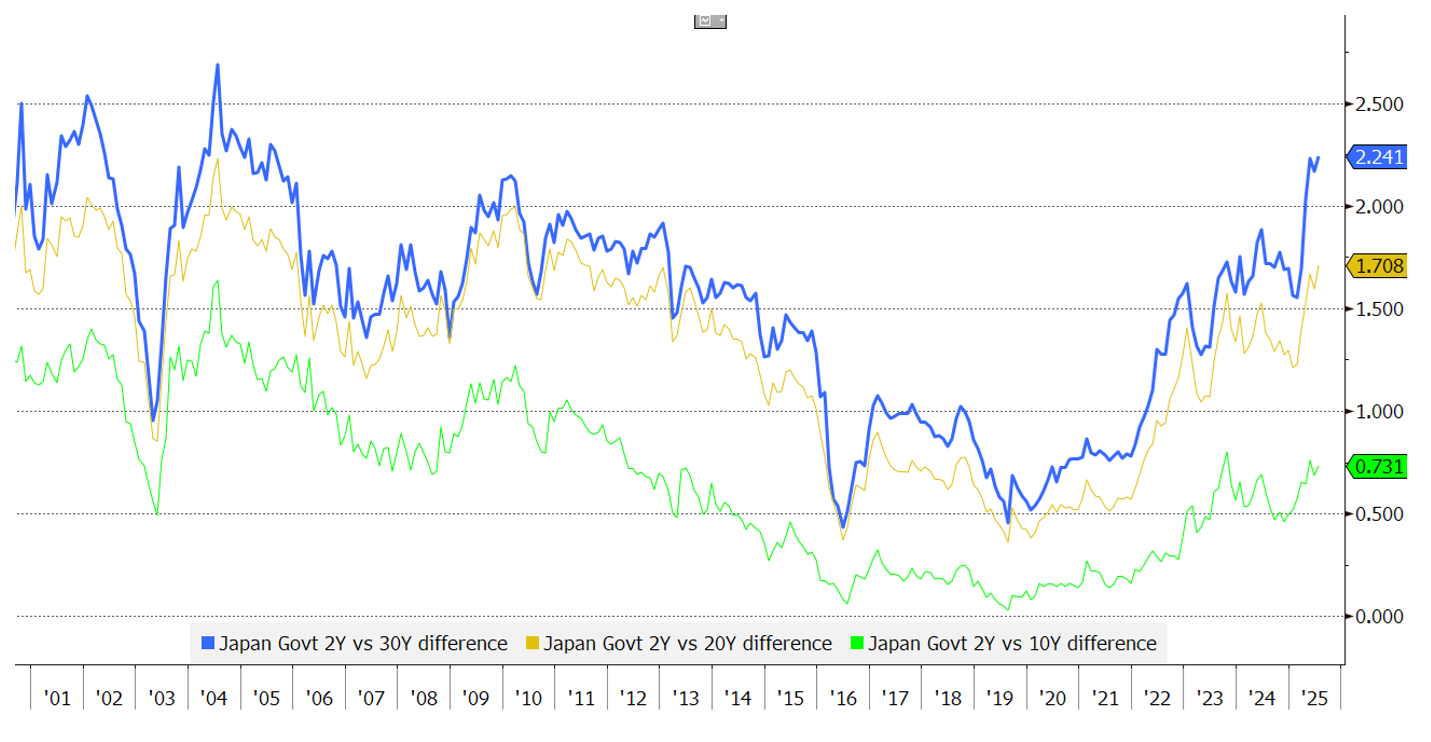

But as well as higher yields, the other significant thing to note is that yield curves are steepening.

Japan Government Bond – Yield Curve Shapes

For most Japanese investors, the main thing they watch is the slope of yield curves. That’s because they buy long-dated bonds and hedge with short-dated FX forwards. Therefore, the steepening of the JGB yield curve is alarming. Especially since the BoJ has only just begun to shrink its balance sheet. The fact that yields in Japan have now picked themselves up off the mat acts as a serious challenge for a government that is running debt/GDP at around 250%. But that is possibly not as significant as the implication for global investment flows.

Our Japan economist, Rini Sen, expects the BoJ to raise rates to 1.75% by the end of 2026 from 0.5% currently. That is much higher than the consensus of ~1%. Even if the BoJ doesn’t get that far, pressures for rates are higher.

No one, including us, is suggesting Japan stops shunting money offshore in search of some high-yielding things. But the marginal shifts are likely to see more money find attractive alternatives at home, where returns are becoming more tantalizing. This acts as yet another headwind to global sovereign debt at a time when, thanks to things like the US Big Beautiful Bill and Germany’s commitment to dramatically increase defence spending, the financing task for Western governments is only going up.

We talk to our Japanese colleagues all the time about non-Yen fixed income opportunities. The discussion quickly boils down to ‘what is my hedged return in JPY and how does that compare with JGB’s’? As yields on the latter move higher, the hurdle rates required for Japanese investors to look offshore go up.

We haven’t altered our dislike of longer-dated sovereign bonds.

.png)

*2003. Koo, C. Richard. ‘Balance Sheet Recession’: Japan’s Struggle with Uncharted Economics and its Global Implications.

2 topics

2 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)