What? Bullish equities? Are you mad...?!

The global economy is demonstrating strong, synchronised growth; annualised for the third quarter of ‘17 the US is showing 4.1%, Europe at 2.5%, China at 6.8%, and even the UK, having blown half its own foot off with Brexit, has the lowest unemployment rate in 40 years at 4.5%. The financial markets are in their 8th year of strong growth, and yet equity market prices are not at extremes in terms of valuation multiples – current S&P price-to-earnings is 21x. Based on current population growth, over the next 12 years another billion – yes BILLION – people will join the global workforce, adding serious productivity and growth to the global economy. Asset prices all over the world are either healthy or skyrocketing. So why isn’t everyone a raging, table-pounding bull?! (Source: Bloomberg).

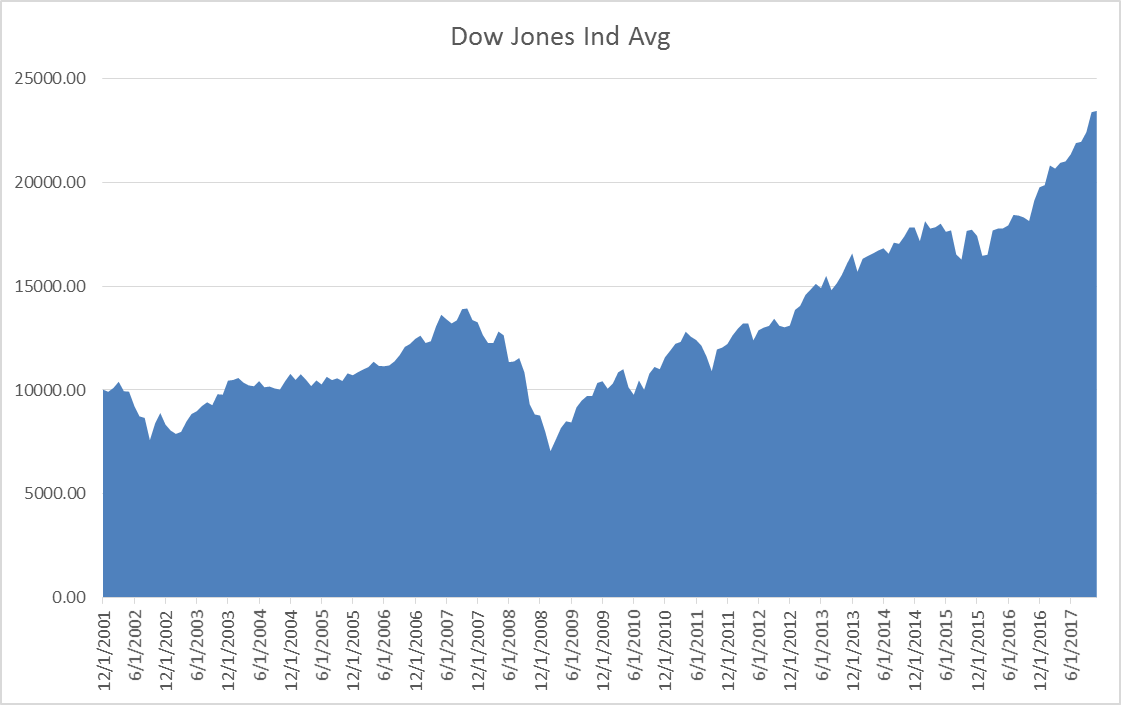

Staggeringly, since its March 2009 low the Dow Jones Industrial Average has more than quadrupled investor’s money, with $100 invested at that low point now worth about $405 (Including reinvested dividends) (Source: DQYDT as at 6th November 2017). But of course, we are all smart with the benefit of hindsight and the point is not one of smart timing – indeed few would have actually crystallised gains specifically from that extraordinary climb – but of the Teflon-like ability of share markets to simply shrug off all that the world has thrown at them these past years. That observation, and the appreciation of the impact of an arguably less cyclical, longer term set of influencing factors set out below that we should perhaps give precedence to thinking about how markets may behave over the coming years. Again, the old lesson of ‘time in the market, not timing the market’ could not be more appropriate.

Technological innovation

Risk you say? Risk of inflation? Technology has simply made inflation obsolete. Sadly, for providers of unskilled, semi-skilled and someday soon even very skilled labor, technology developments mean that every time labor costs rise significantly, companies (and governments) will replace those hardworking people who expect vacation days, health plans and retirement pensions with computers who will do the jobs better, more cheaply and without complaint. These computers will never go on strike and never negotiate for a raise. This substitution effect is incredibly powerful. Someone please tell us any scenario where this does not serve to cap future wage inflation for our lifetimes.

But how does this benefit equity growth? In principle the investing in and trading of tech stocks today is little different from the advent of basic bartering by prehistoric toolmakers, possibly the earliest example of technology cementing itself as a perennial tailwind benefit to capitalism. Mechanisation, transportation, industrialisation, communication, miniaturisation, automation, computerisation, mobilisation, virtualisation… each additive to what has come before in creating an almost unstoppable capital-consuming force, and one today that has provided rich opportunity for equity investors.

Central bank ‘put’

Risk of financial crisis you say? Central banks around the world have been engaged in an on-the-job training program since the 1990s. They have well and truly studied the Greenspan Put, graduated with honors from the Bernanke Helicopter Money School, received their PhDs from the Draghi “Do Whatever It Takes” Institute, and then had all doubts erased by radical laboratory work in the Japanese “No Matter What We Do Nor How Much We Spend There Can Be No Inflation Experiments”. Even better, financial market participants know that their central banks with their currency printing presses have been studying very hard. Volatility in markets tells us that the smartest and richest financial professionals judge risk in financial markets to be at record lows, reflecting full and extraordinary confidence that should there be any hiccup with financial market prices the central bankers will swiftly pull out their Bernanke capes and buy assets until stability returns.

Take your pick. The Reserve Bank of Australia, US Federal Reserve (Fed), Bank of England, Bank of Japan, or the European Central Bank for starters. They have all proven time and time again in recent history to intervene immediately post-crisis, providing necessary refuelling of equity markets through cheap/free cash and bond buying. Will they be there forever? Only time will tell but a precedence appears to have been well set. For now, we believe that central bankers will be predictable, boring and slow!

And yet, if you talk to government officials, financial professionals, women in the street, taxi drivers, or if you read ANY newspaper, you learn this is all incredibly fragile, unsatisfactory for many people and headed for doom. You, yes YOU, are probably scared of investing in equities and risk assets judging by the extraordinary amounts of cash deposits in Japan, Europe and the US despite substantially no positive return being paid on all those (indeed sometimes even negative returns via administrative charges). So what in the world is going on here? Our brains are telling us to be very bullish in our investing and our stomachs are telling us to be careful. Why and what should we do about it?

Change in retirement systems

A change more visible in certain parts of the world – Australia a case in point – where a quiet generational shift has occurred, with retirement provision moving away from the standard insurance-based, employer-provided retirement income dominant throughout much of the 20th century to the investment-based employee-responsible defined contribution structures of today. Eventually the savings via retirement plans or creation of personal wealth has to find its way into financial markets. Newer retirement income models that largely place the responsibility of provisioning for retirement on individuals own shoulders fundamentally calls for a far higher proportion of growth/risk assets, and more specifically a degree of liquidity, propelling systemic long-term allocations to equity markets. Coupled with the following trend it is difficult to see a reversal of this longer-term trend. Everyone wants their money to work harder for them so they don’t have to.

Increases in life expectancy & population growth

Better education and healthcare have undeniably driven an overall increase in world population, and at an accelerating pace. Larger and better educated workforces and greater lifestyle expectations all drive demand for goods and services higher, fuelling corporate development and growth in the underlying equity.

Demographics plays an important role in predicting asset price returns. Advancement in medical technology and eradication of certain diseases has resulted in a lower infant mortality rate and an increase in life expectancy levels throughout the world. As people live longer there will be more demand for food, water, electricity and resources in general. Companies will have to fulfill the need for this insatiable appetite for goods. The more the companies provide and adapt the better it is for their owners (shareholders).

Globalisation and universal consumerism

A growing ‘glomadic’ population (the new term for yesterdays ‘world citizens’), commercial globalisation, collapsing trade barriers, and general shrinking of the world (read improved transportation and ease of mobility of people), plus advent of the internet and social media, and the playing field has been levelled forever! It wasn’t that long ago that consumer markets globally still operated with regional barriers. You stocked up on Levi’s when you travelled to the US, you only drank Evian in France, had to go to Australia to drink Fosters. Now manufacturers are adept at creating and distributing ‘global’ product – the well-known case study of Apple a prime example where it is still possible to put one of everything Apple makes on a surface no bigger than your average dining table (that statement becomes a little tricky if we see an Apple car at some point…). The expansion of the internet as a giant single shop window fuels a universal demand and consumer aspiration like nothing seen before, and today we all expect to be able to buy the same goods and services at (more or less) the same price wherever we are in the world. Behind the scenes a global business framework of internet retailers, of innovators in logistics, distribution, and shipping, become ever richer and thank you for your unrelenting worship at the altar of consumerism and your constant demand for strawberries in winter and the latest Nike runners and the newest season of GoT barely after the cast and crew have finished their ‘that’s a wrap’ celebrations.

Politics and fiscal policy

Almost as rare as a week at the White House passing without a controversial tweet, or a non-populist political appointment, are fixed income managers making bullish statements about equity markets.

Of course it always depends on the perspective you take. For sure there remain a number of destabilising ‘clouds’ around the world – threat of a nuclear North Korea, (in)ability of the Trump administration to pass meaningful tax reform, the uncertainty of a smooth Brexit, the fragile health of the European banking sector, to name a few. However, despite these and the numerous other global political and macroeconomic speedbumps of the last decade, what is irrefutable is the relentless, grinding upward progress of global share markets.

If we consider recent and current political development – Trump, Brexit, Corbyn, Macron, Catalonia, the rise of the hard right and hard left around the world, what we can see is a huge cross section of modern democracies suffering from fractionalisation and protest voting. We can see huge segments of these people feeling threatened and left out by the globalisation of capitalism. We can see that the benefit of low inflation is the same as the cost of no real wage growth, and that employed people around the world are suffering their lack of economic power and using their democratic vote to complain. So, what is an investor to do? What is a person or a citizen to do?

We know of no solution to the social problems created by the loss of relative bargaining power for labor in a modern, ‘efficient’ and globalised economy. Modern democracies will continue to be beset with weak public balance sheets which are inadequate to pay for increasingly long and expensive retirements (healthcare will remain the leader in global inflation). Our global economic growth will be strong, but plagued by dissatisfaction. In short, the social problems are going to get worse until we figure out a way to generate substantial increases in real wages and to communicate about that success in a way that satisfies a democratic supermajority (Kibbutz anyone…?). We don’t know anyone who sees that on the near-term horizon. Expect more protest votes, radical outcomes and upheaval from distressed political systems around the globe. This will create waves of extreme regulation and will detract from global potential growth. But still…

This will continue to pressure banks and insurance companies, as well as the many business models that rely on borrowing short and lending long. However, the strength of the global system is easy to gloss over when overwhelmed by the very important social and democratic concerns of the day.

How high

By no means exhaustive, we increasingly give credence to these ‘super-secular’ changes that have and will continue to drive risk markets over the longer term. Our expected dominance of these longer-term themes does not of course remove the chance of periodic corrections in risk markets, but perhaps sets them in a wider context suggesting a greater degree of prudence when considering the significance of short term losses. Modern markets display an increasing resilience and ability to rapidly bounce back. There remains a challenge for those relying on equity investments who are nearing retirement drawdown phases (and that’s where balanced portfolios and fixed income managers play an ever-important role), but basic financial planning principles of dollar-cost-averaging in and out of risk assets over time to mitigate the risk of a ‘cliff’ fall in value and an impossible recovery come into play.

We are certainly not alone in our thinking. The Sage of Omaha himself is on record for suggesting the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) will exceed 1,000,000 in 100 years (perhaps a little tongue in cheek as unless human cryogenics advance significantly it’s unlikely he will be around as a witness to be called on it one way or the other). However, the basis of his assertion is that 100 years ago the index was just 81, and to get to 1,000,000 from where we are today requires a compound annual return of just 3.87%. Considering over the past decade – which includes the troublesome period of the GFC – the DJIA rose by almost 9% a year, that feels conservative to say the least. (Source: DQYDT, November 2007 – November 2017).

Rule of 72

The rule of 72 says if you divide 72 by your expected rate of return the resulting number is roughly how many years it will take your money to double. For example, if you think your returns are annualized at 7% then you would expect to double your money in 10.3 years (72/7).

If you believe that nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grows at 3% and the Fed manages inflation of 2%, then it is reasonable to assume that stocks rise at that rate (3% + 2%), plus dividends should boost total returns to 7%.

The inflation adjusted average annualised return (including dividend reinvestment) of the DJIA for the period January 1982 to November 2017 is 9.9% (Source: DQYDT). For longer term between 1950 and 2017 if you adjust the DJIA for inflation and account for dividends, the average annual return comes in at 7.5% (Source: DQYDT). How many of us believe over the next 10 years that we will make at least 7% returns a year on our equity investments?

Conclusion

The strength of a synchronised global growth cycle is undeniable, almost as much as the certainty that there will be occasional corrections along the path – but central bankers will act to smooth the worst of those corrections with their newfound tools of radical intervention and asset purchases. Populations will grow, and so will technology-driven productivity. The business cycle will continue to wax and wane, but through it all global GDP growth will be reasonably strong, and financial assets like equities and property will continue to increase in value. Technically, yield curves will probably remain flatter as central-banker driven low volatility remains a persistent feature of our new global reality.

Focusing on the economics of investing, the most likely future scenario of all does include some 10-15% corrections in various equity and asset markets. No, we are not predicting some high growth nirvana from here; more like a moderate and consistent global growth story beset with democratic and social upheaval, but including growth necessary to support an upwardly grinding Dow. Even conservatively if you assume that equities return an average 7% annually from here – the Rule of 72 suggests the DJIA at 50,000 in little more than 10 years from now!

So, put your fears to bed, ramp up your risk appetite and bet on it. When you wake up one day to a big market correction, roll over and enjoy a ‘lie-in’. This too shall pass and shall revert to longer-term growth patterns.

For more insights from Kapstream Capital, visit our website: (VIEW LINK)

Unless otherwise specified, any information contained in this publication is current as at the date of this report and is provided by Fidante Partners Limited (ABN 94 002 835 592, AFSL 234668) the issuer of the Kapstream Wholesale Absolute Return Income Fund (ARSN 124 152 790) (Fund). Kapstream Capital Pty Limited (ABN 19 122 076 117, AFSL 308870) is the investment manager of the Fund. It should be regarded as general information only rather than advice. It has been prepared without taking account of any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of that, each person should, before acting on any such information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to their objectives, financial situation and needs. Each person should obtain the relevant Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to the Fund and consider that PDS before making any decision about the Fund. A copy of the PDS can be obtained from your financial adviser, our Investor Services team on 13 51 53, or on our website (VIEW LINK). If you acquire or hold the product, we and/or a Fidante Partners related company will receive fees and other benefits which are generally disclosed in the PDS or other disclosure document for the product. Neither Fidante Partners nor a Fidante Partners related company and our respective employees receive any specific remuneration for any advice provided to you. However, financial advisers (including some Fidante Partners related companies) may receive fees or commissions if they provide advice to you or arrange for you to invest in the Fund. Kapstream Capital, some or all Fidante Partners related companies and directors of those companies may benefit from fees, commissions and other benefits received by another group company.

1 topic