What if bonds don’t hedge equity returns anymore?

Do bonds hedge equity returns? The answer is essential for portfolio constructors. Bonds haven’t done so recently and may remain less useful, in that regard, than we have become accustomed to over the last few decades. Whilst bond yields have now risen well off their QE lows, the role of bonds in portfolios may not have recovered to their Pre-Covid levels. Bond/Equity correlations have generally been negative since the late 1990s, but there are reasons to think that things have changed. Relative to the Pre-covid period, for strategic asset allocation purposes, the debt component of many portfolios should have less interest rate duration and more credit exposure.

Bonds are less useful for portfolios if they don’t hedge equity returns

Strategic Asset Allocation settings generally trade-off expected returns and estimates of volatility. Whilst capital markets specialists, who develop the SAA assumptions, place significant focus on developing forward-looking return expectations they often draw strongly from observed returns over the prior 10 or 20 years as a starting point for volatility and correlation assumptions. The more sophisticated may make various adjustments to scale the volatility or correlations, but it might be that the key correlation assumption for equities and bonds needs a little more renovation than that.

A significant reason for allocating to bonds has been an expectation that they will hedge equity returns, which is usually the most dominant risk in portfolios. A hedge for equities should be expected to produce a positive return when equity returns are negative. It should have an expected negative return correlation with equities.

Over the last 20 years, monetary policy has worked to support equity markets during extreme events like the GFC and the onset of covid. The actions of central banks, by cutting rates and introducing quantitative easing and other measures, forced bonds to rally whilst equity markets fell and this significantly contributed to the observed negative correlation between these two asset classes.

Nonetheless, there are major macro drivers which appear to be evolving in a way to unhelpfully synchronize bond and equity returns.

For example, if a long trend towards integration of supply chains slows or reverses, giving way to friend-shoring or self-sufficiency, it can contribute to higher inflation volatility for production inputs due to reduced scale and diversity. These outcomes are expected to interact with (consumer) inflation-targeting monetary policies to produce positive correlations as they have more recently.

Should the conditions in the period ahead combine to make bonds a mere diversifier, except in the case of financial instability, there simply is less of a role for them in long-term strategic asset allocation settings in many cases. Unless the return expectations for bonds improve relative to floating-rate credit by enough to offset these effects, the most obvious adjustment to consider is reducing the exposure to fixed-rate bond exposures and allocating more of the risk budget to floating-rate credit in some form. This is particularly if investors favour keeping overall growth/defensive allocations largely unchanged over time.

The equity-bond correlation over the last 20 years

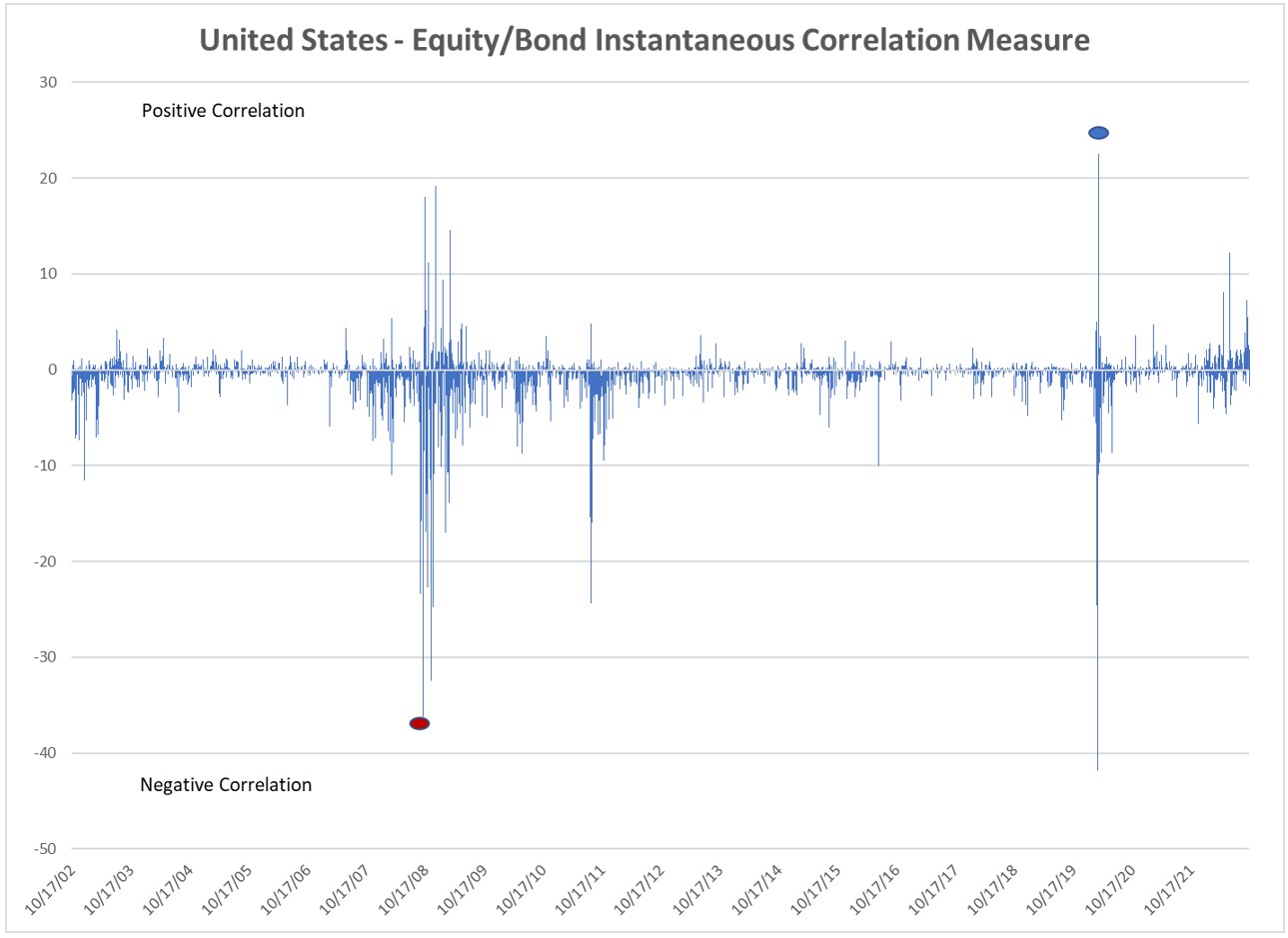

The following chart illustrates the correlation behaviour of equities and bonds for the United States over the last 20 years, on a daily basis. When the returns are relatively larger in each case and move in the same direction, this is recorded as a positive correlation outcome. An example is 18 March 2020, when the US Treasury market melted down in the middle of the covid sell-off in equity markets (highlighted in blue). Conversely, if the returns are large and move in opposing directions, this is recorded as a negative correlation outcome. An example is 29 September 2008, when the Fed and other central banks stepped in to provide a significant liquidity injection during the GFC. Bond markets rallied as 10-year yields fell 27bps (bond values rise as yields fall), but the equity market fell nearly 9% on the day in any case (highlighted in red).

For the technically inclined, these are the product of the daily return z-scores between the two asset classes.

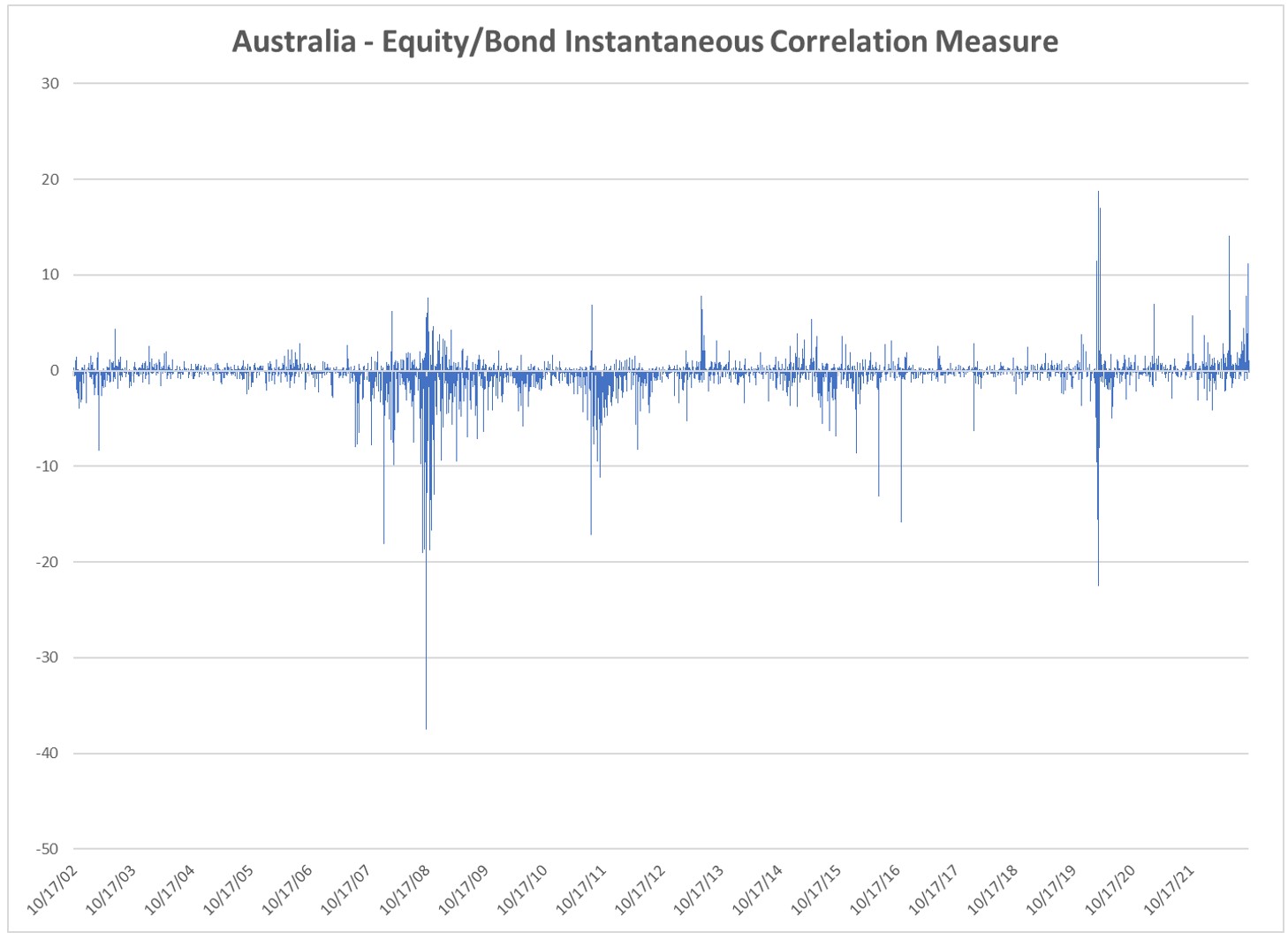

The equivalent chart is shown for Australia:

From these two charts, we can see that the bars are generally below zero, with the largest clusters around periods like the GFC (2008), the European Debt Crisis (2011/12) and during Covid (2020). However, the general character visually shifts from late 2021 when the thesis of transitional inflation pressures was set aside and even more so when Russia subsequently invaded Ukraine. The bars are generally positive from then and often reflect the impact of upwards revisions to the expected level of inflation for various reasons.

The effect of demand and supply shocks on the equity-bond correlation

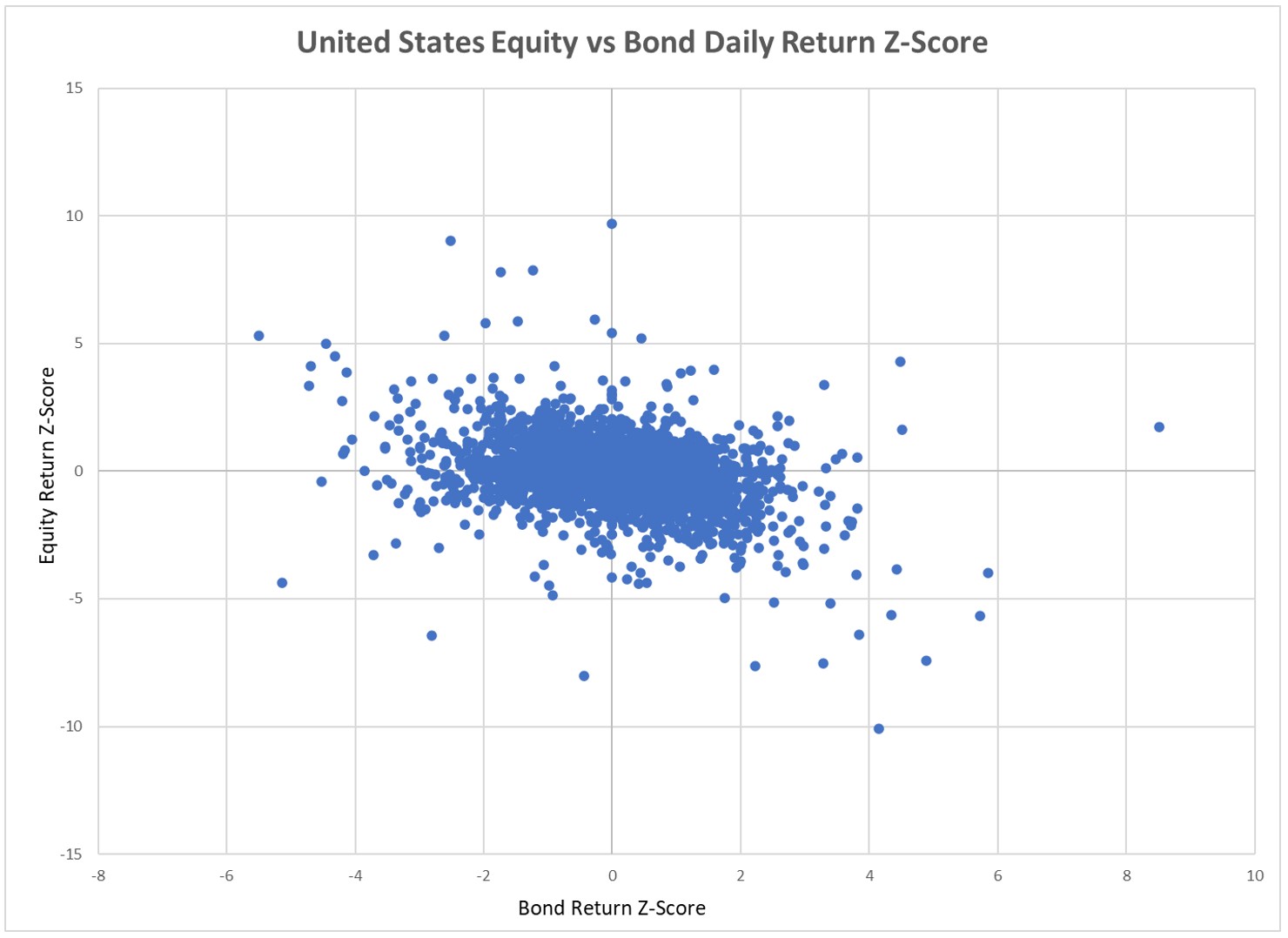

Another way to visualize this is via a dot plot of the daily standardized returns for the US over the twenty-year period. The negative correlation is clearly visible:

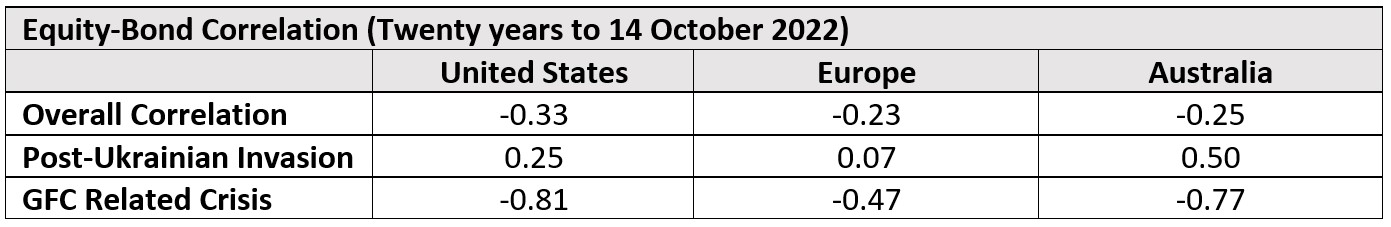

However, if we isolate different periods and determine the correlations within them an interesting picture emerges. The following table shows the correlation over the full period and two additional sub-periods. The Post-Ukrainian Invasion period is measured from 23 Feb 2022. The GFC related Crisis is measured from when Bear Sterns required Federal Funds to function (14 March 2008) through to Draghi’s ‘Whatever it Takes’ Statement (26 July 2012) which we consider being the acute period of the GFC-related turmoil:

There is a distinct difference in the character of the relationships. The GFC is generally characterized as a demand shock due to the sudden limitation of credit growth available to finance investment and consumption. In contrast, the post-Ukraine invasion period is characterized by a significant energy supply shock.

At this level, it is visible that the equity-bond correlation outcomes are influenced by the dominant nature of the shocks impacting the economy.

Under an inflation-targeting regime, central banks tend to lean against demand fluctuations to keep inflation outcomes steady. If the mood of the economy should lead to an increase in demand, prices will rise and company profitability will generally improve. This tends to exert upwards pressure on equity prices. However, central banks will seek to moderate the rise in inflation by tightening interest rates, causing the value of bonds to fall. Hence, where fluctuations in demand are the dominant type of shock the economy experiences, and central banks pursue an inflation-targeting regime, bonds generally hedge equities.

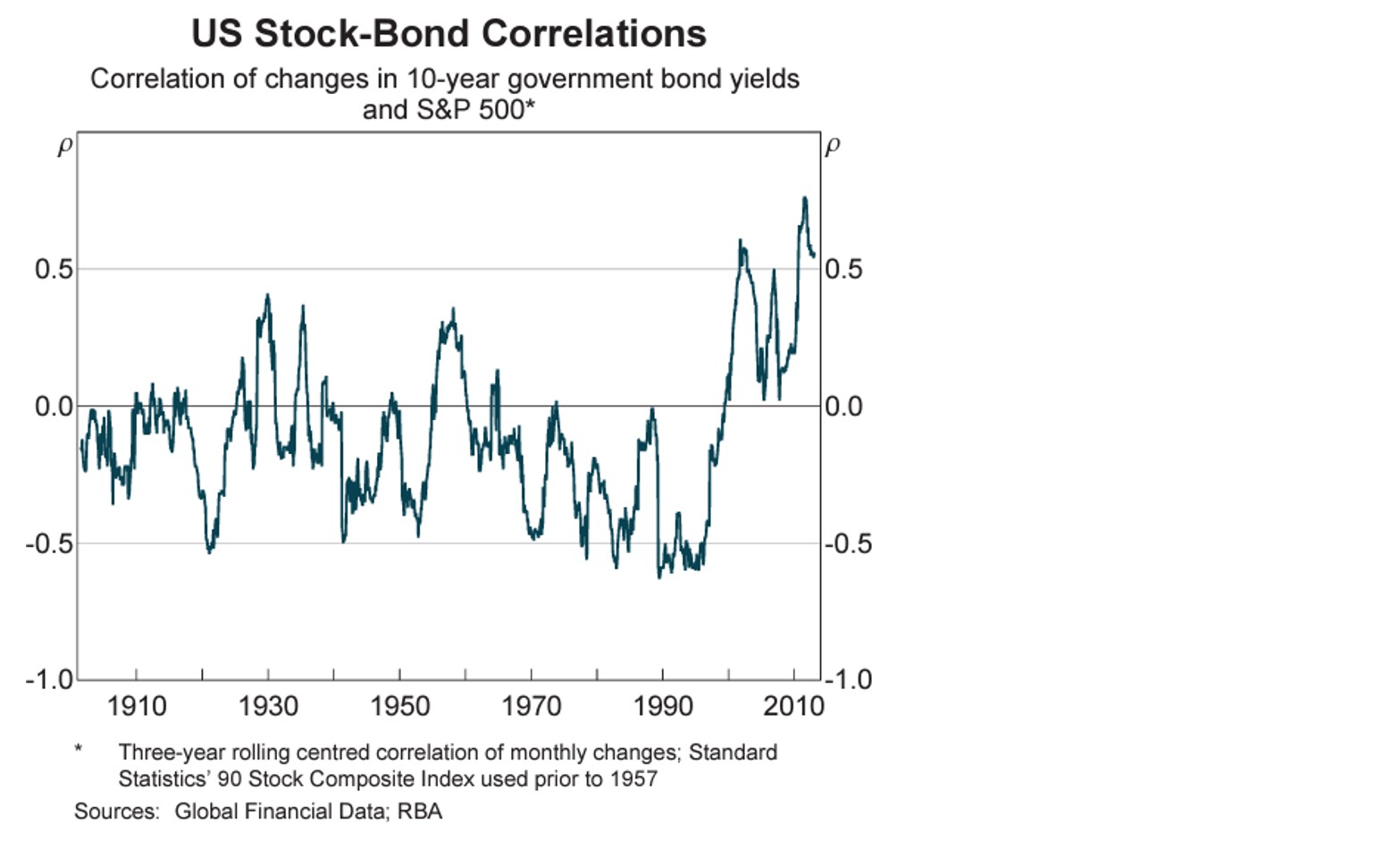

Prior to the 1990s, central banks pursued aims that were different to an inflation target. For example, the RBA targeted external factors like the current account and Fed Funds Rate prior to this. It is instructive that bonds generally have not hedged equities for any prolonged period of time until inflation targeting became de rigueur. This chart, which was produced from RBA research into the matter in 2014, illustrates the step change although not all of this effect is attributable to the revised reaction functions:

Supply shocks produce different effects. Putin’s decision to cease supplying gas through Nordstream2 produced a supply shock. It meant that the cost of producing goods (and some services) generally rose sharply. Many companies found it harder to maintain their margins. Earnings fell, share prices fell and central banks tightened interest rates which made bonds fall in value. The equity-bond correlation tends to be positive in the face of supply shocks, and bonds cease to hedge equities when the influence is strong.

Supply shocks can come in different forms as well. As we recently saw in the UK when the Truss/Kwarteng combination rocked equity, bond and currency markets with their heterodox economic theories, a shock to credibility functions much like a regular supply shock. Unless central banks intervene, sovereign debt crises produce similar effects..as, apparently, do global pandemics.

Reasons why the next few years are unlikely to be like the last twenty

For the 20 years prior to covid, large trends created circumstances where demand shocks were the more dominant influence. Supply was responsive to shifts in demand, geopolitics did not intrude as much into the daily lives of the developed world, technology and globalization provided stronger productivity gains and demographics were favourable. This fostered improved trade integration. Labour and capital markets were increasingly deregulated. Firms also had an increasingly global talent pool to draw from and client base to sell to. This has kept inflation low and stable.

Additionally, central bank responses to challenges like the GFC and covid produced periods of very significant negative correlation which are, hopefully, unlikely to repeat often.

However, change is taking place. Importantly:

- Productivity growth is slowing, making supply less responsive;

- The bargaining power of labour is rising due to demographics and low unemployment;

- The physical distribution of intellectual property and key basic resource extraction, where sources and end demand pass across national boundaries of competing state actors, have created critical dependencies that geopolitical considerations demonstrably exploit. Efforts to offset these increase supply-side influences;

- Expenditure relating to transitioning our energy infrastructure and increased strategic risks arising from China’s revisionist perspective require exceptionally large physical investments to be made at a time when the capacity to produce them is tight; and

- Globalisation of capital flow continues to increase and, when coupled with higher financial fragility, creates a higher sensitivity to shifts in preparedness to bear the investment risk.

Productivity growth is lower

The productivity growth assumptions in Australia’s recent Budget were lowered and this reflects a wider global observation. Productivity gains have been harder to secure in the post-GFC era. The easier gains from integration have been won.

When productivity gains are hard to secure, supply cannot respond as well to shifts in demand. This makes variations in demand more likely to create inflationary pressures and gives such developments more of the character of supply shocks. For example, if the world could not produce any more oil per day, and demand increased, all that would happen is an increase in oil price inflation which central banks would need to lean against via tighter monetary policy.

Rising bargaining power of labour

China’s working-age population peaked in 2014 and its overall population now appears to have peaked. Along with similar patterns elsewhere, the supply of labour will not be as abundant and dependency ratios are rising. This will increase the bargaining power of labour and may contribute to a reversal of deregulation that has been a feature of the economic framework since Thatcher and Regan. As we are seeing hints of today, this increases the stickiness of inflation and increases the probability that shocks of a supply-side nature will be more influential on financial markets from here.

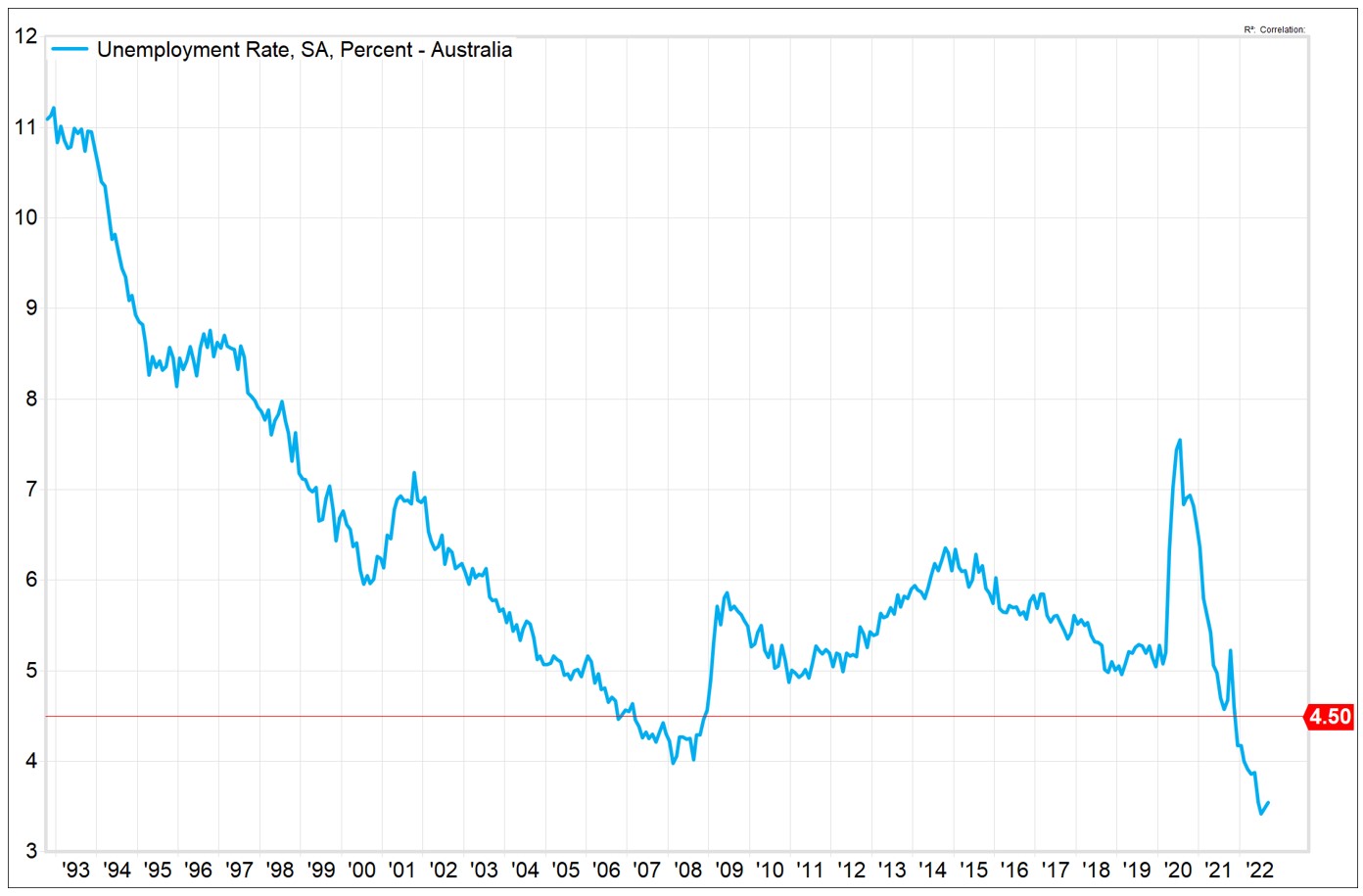

The outlook for unemployment, even if a shallow recession should occur, remains very supportive for the bargaining power of workers. For example, the Federal Budget assumes Australian unemployment will only rise to 4.5% by 2024, which is historically very tight:

Critical materials and intellectual property

The experience of covid and the Ukrainian conflict created a significant premium on the reliability of supply chains. Supply chain interruptions during covid reminded us that lean inventories brought higher risks of disruptions. However, the Ukrainian war has changed the landscape dramatically too. The tools deployed included significant sanctions, denial of energy supply, weaponization of banking systems, stricter demands on settlement currencies, seizure of energy assets, and blockades of trading ports. It forcefully reminded us of our interdependence and how it can be exploited.

China’s geopolitical assertiveness is creating additional fault lines. The risk of supply shocks of a geopolitical nature appears higher now than for much of the prior 20 years.

Whilst some supply chains can be readily diversified, others are more difficult. For example, the US has now curtailed exports of high-end semiconductors to China which are critical to developing AI and other advanced applications. If Europe and Japan join this initiative, China has limited immediate ability to respond. In turn, US manufacturers are concerned that China will deny them market access, as it did for Australian coal and other goods.

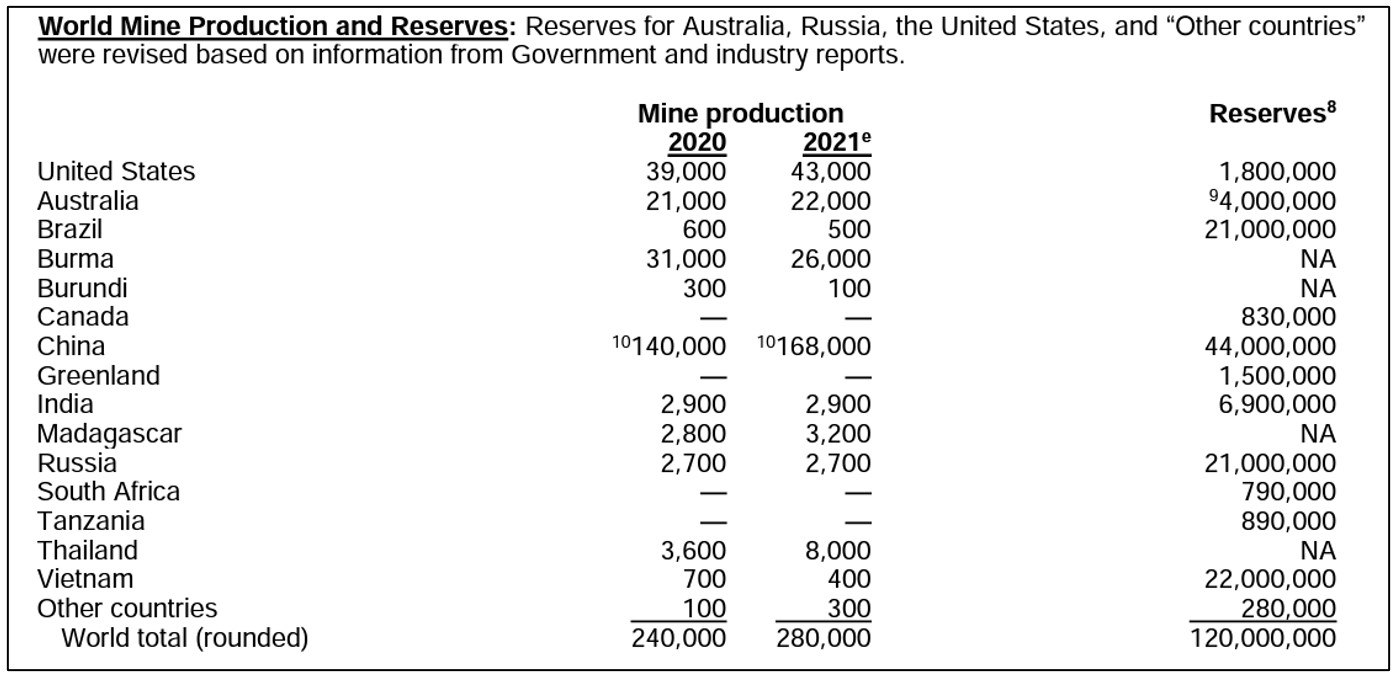

On the other hand, China’s significant mineral deposits of rare earths is also a critical vulnerability for the rest of the world as we seek to develop renewable power sources and electrify our power consumption to combat the threat of global warming. China’s dominant position with rare earths is similar to OPEC’s position with oil in the 1970s. It is notable that critical minerals deposits have historically taken over 16 years on average to develop.

The following table is taken from the US Geological Survey’s 2022 report relating to rare earths, and show’s China’s significance in terms of reserves and extraction:

As if on cue, OPEC has recently reminded the world of its ongoing influence and is determined to deny the world an opportunity to lower inflation by cutting planned production. In response, NOPEC legislation which has been winding through Washington for years is making headlines and has moved to the Senate floor. If passed, it will change the US relationship with OPEC significantly and the risk is now much higher given the US has now become a net energy exporter.

It is not necessary for all world trade to fragment to increase supply-side risks. What matters is that critical elements of supply chains are fragmenting. It won’t stop here. Whilst friend-shoring of supply chains may make them more resilient to geopolitical shocks, it may create more price volatility in ordinary market settings as scale and diversification is reduced.

Many of these issues will become acute if China’s designs on Taiwan move to a more overt posture. US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has recently suggested the time frame for this has been brought forward significantly as China’s President Xi further consolidates power.

Energy Infrastructure and military expenditure

Astronomical figures are required to successfully meet a net-zero emissions scenario by 2050. These will drain capital and labour from other sources and contribute to keeping these markets tight for decades to come. Meanwhile, planned investment into energy infrastructure is presently insufficient for this to go smoothly.

At the same time, the heightened geostrategic security concerns will see a shift towards higher military expenditure where hardware will increasingly be developed with a view towards self-sufficiency.

The world is expected to be operating with little spare capacity for the time being.

Financial Stability and Increasing Globalisation of Finance

Credit growth has continued to drive the economy forward, making financial markets more fragile and increasing inequality. This is visible today as financial stability concerns emerge as a potential foil to central bank efforts to ensure inflation returns to target levels. It has narrowed policy flexibility.

We recently witnessed this with the failed Trussonomics experiment. The loss of confidence it created led to a correlated sell-off which permeated globally. The fire sale of assets related to satisfying margin calls for liability-driven investment strategies in the UK was felt as far as public structured credit in Australia. Whilst the BoE was compelled to step in and provide liquidity support, its prior commitments to commence QT meant that the support had to be short-lived.

The extent of global financial linkages is illustrated in the latest FX Survey by the Bank for International Settlements which reported an average daily turnover in FX of USD 7.5tr, up 14% from three years ago.

The combination of high overt leverage (eg. High debt to GDP for Italy), underlying leverage (eg. margin calls on UK Pension funds to support derivative positions) and globalized capital flows creates circumstances where shifts in risk appetite accelerate quickly and produce correlated asset class returns.

These developments are visible and contribute to our assessment that supply-side issues, including general dislocations in risk markets, will have greater prominence in the period ahead than they have had in the last 20 years.

As a result, it would not seem wise to base correlation assumptions on the last 10 to 20 years. Whilst we do not expect the positive correlations observed following the Ukrainian invasion to persist indefinitely at that magnitude, the argument for a negative correlation between equities and bonds has become harder to sustain.

How changing the correlation affects portfolio construction

The appropriate outcomes for considering this issue will vary depending on the specific circumstances of any investor and our comments here are necessarily general in nature. However, as we increase the assumed correlation between bonds and equities, the optimal portfolio allocation to bonds generally falls.

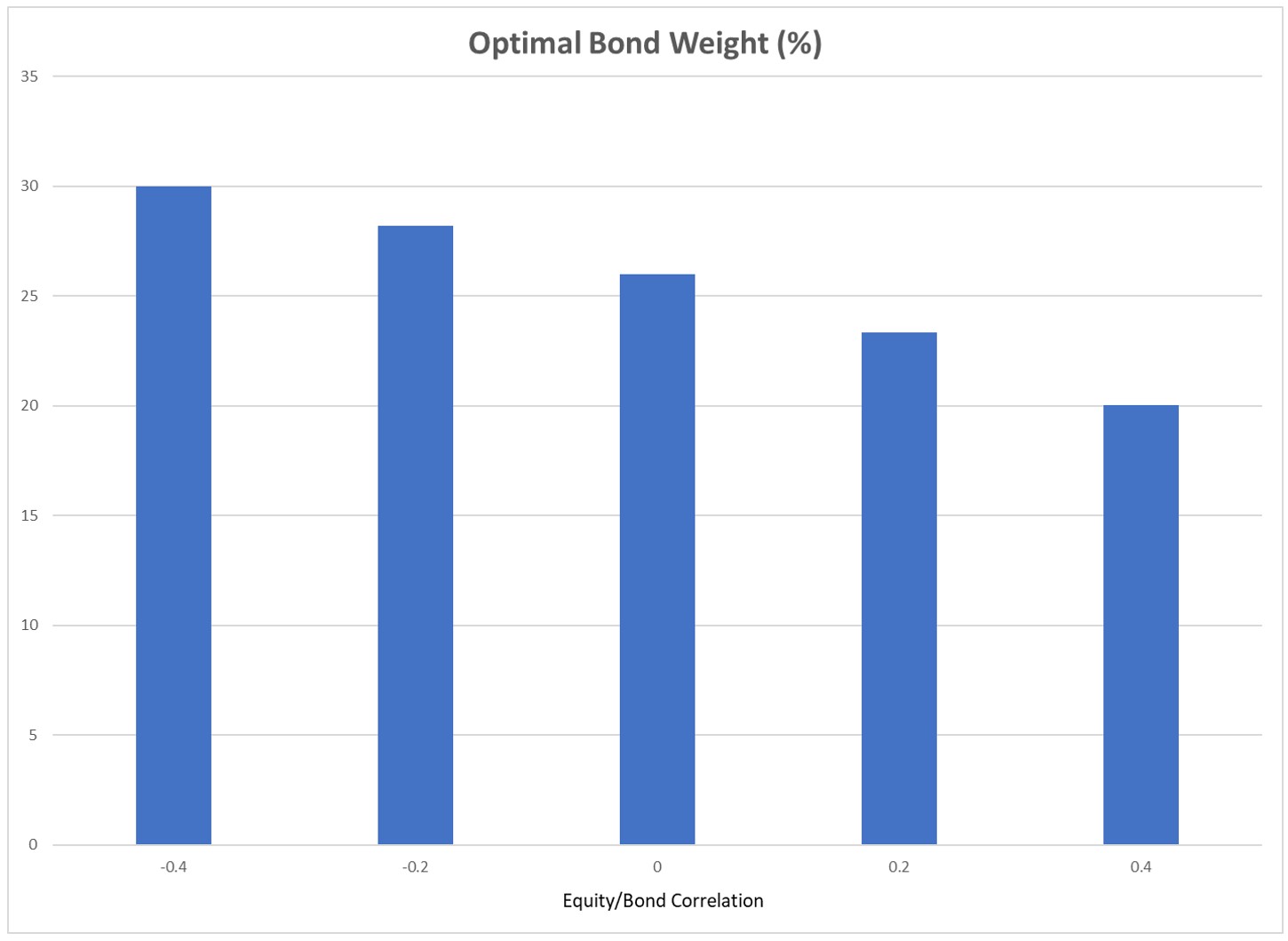

The following graph calibrates a simple portfolio optimization consisting of only two assets: equities and bonds. It assumes a bond term premium of 1% per annum, equity risk premium of 4% per annum, equity volatility of 15% and bond volatility of 4%. We use a standard mean-variance utility function that prefers a 70/30 portfolio when the correlation is -0.4.

This is the traditional approach to portfolio construction. It assumes investors prefer higher returns, but also seek to avoid volatility in asset prices. Naturally, investors have different circumstances and tastes. When presented with the same set of choices, a more risk averse investor will prefer portfolios whose expected volatility is lower and would sacrifice expected returns to achieve this.

In the highly simplified example shown here, we identify the degree of aversion to expected volatility such that the investor prefers a 70/30 portfolio when the correlation between bonds and equities is -0.4. We can then observe how this investor’s asset allocation preferences change as we vary this assumption alone. This will provide some indication of how much an optimal portfolio allocation to bonds might change if the correlation rises.

The following chart shows the optimal bond allocation as we increase the correlation:

Depending on your perspective of how much the correlation assumptions should change, say by raising estimates for correlation by the order of 0.2 to 0.4, bond allocations may need to be reduced by approximately 2.5-5% below the pre-covid norms.

In practice, many investors tend to retain the same growth defensive mix in their portfolios despite these assumption changes, preferring to vary exposures within the growth and defensive assets instead. If so, they would find themselves naturally gravitating towards floating rate credit.

When these concepts are applied to multi-sector credit portfolios, where bonds remain part of the mandate, a similar conclusion arises. In our key multi-sector portfolio, adjustments we made to our assumptions many months ago now produce bond risk allocations that are approximately 60-90% of what would otherwise have been the case. We expect this will be so for the next few years as supply-side risks, and other risks producing similar effects, remain more influential for economic developments than they have been in the prior 20 years.

2 topics