What might a review of the RBA find?

Coolabah Capital

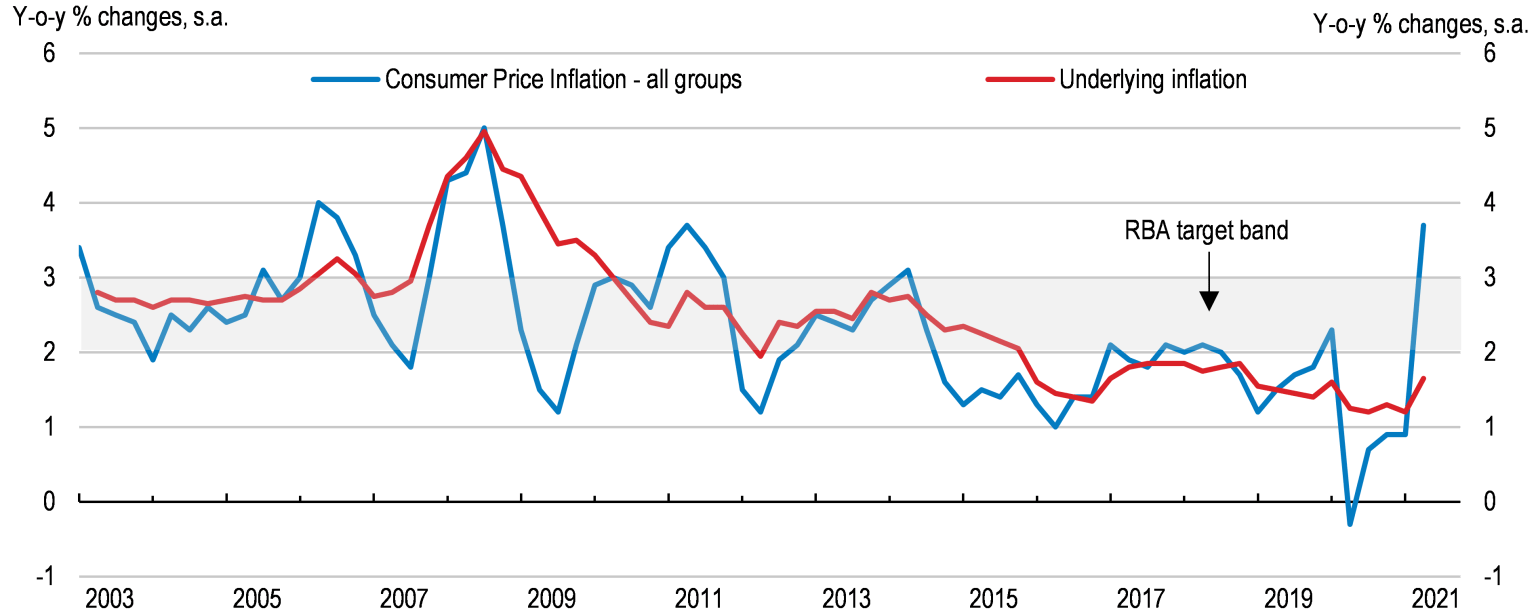

This week, the OECD recommended a review of the RBA. They noted the persistent undershooting of inflation, and a variety of factors that might have led to over-tight monetary policy.

Following the OECD's report, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg opened the door to a review. The Australian Labor party has supported a review of the RBA for some time. So, it seems very likely we're going to have one.

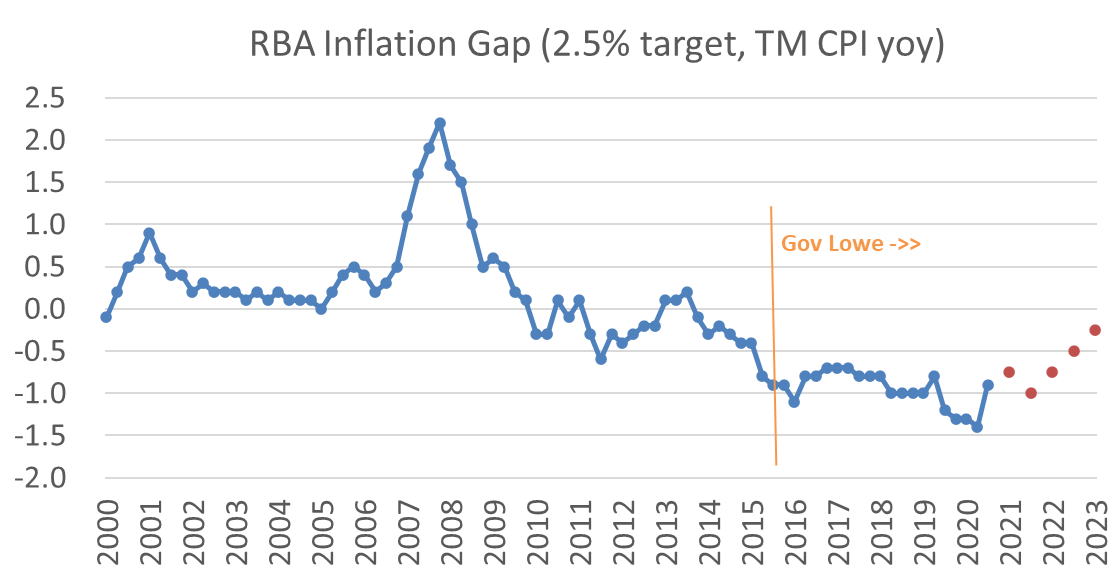

A review is going to show that something happened to inflation in the middle of the last decade. Around the time that Lowe took over from Governor Stevens. While it may not be Lowe's fault, it would make life hard for Gov Lowe and the RBA. The looming review makes it very unlikely that the RBA will raise their target cash rate before core inflation gets back to 2.5%yoy.

What might a review find?

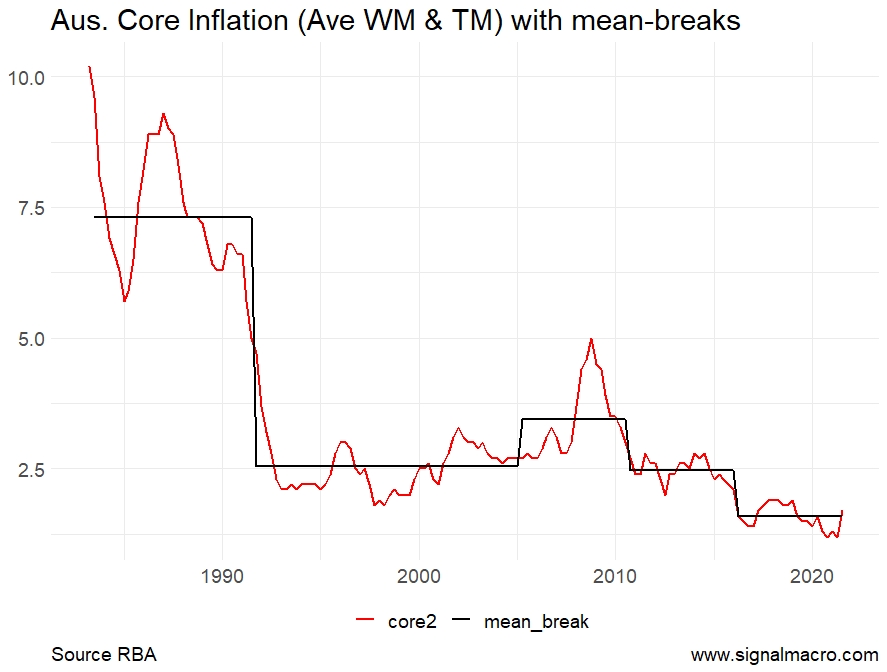

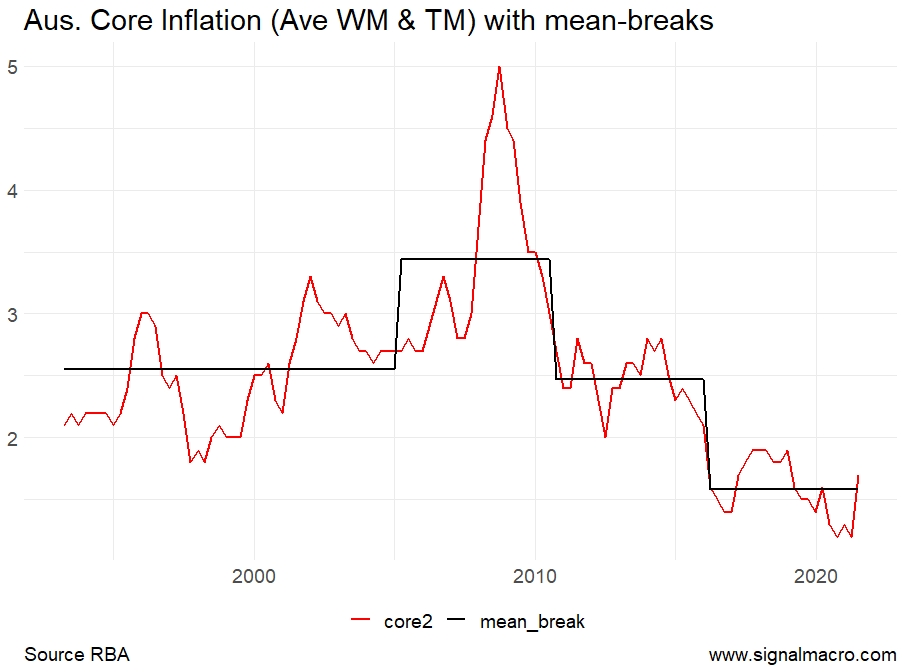

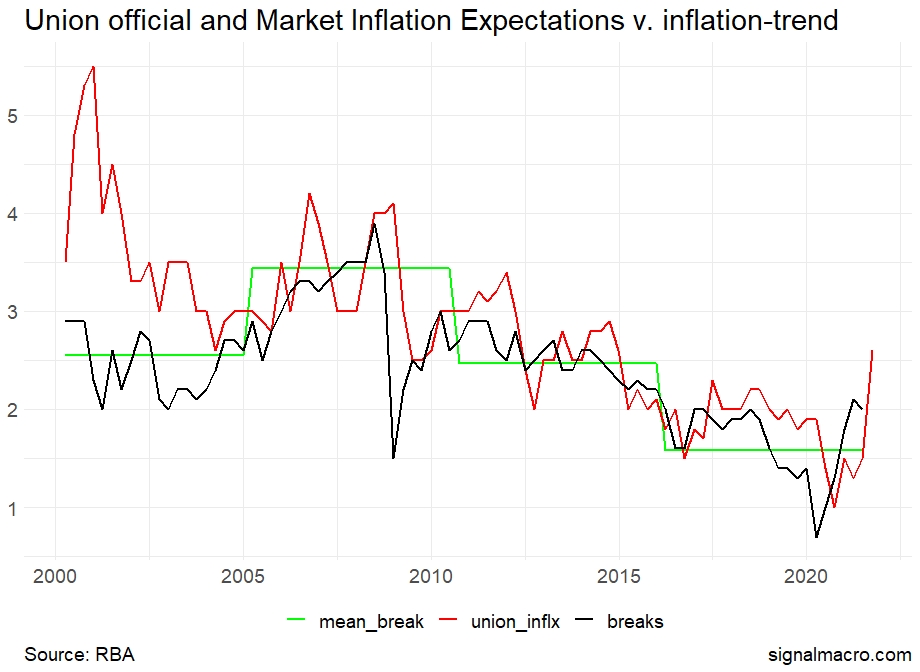

A review of the RBA’s performance since the GFC would find that that there has been a structural break of trend inflation. Statistical analysis suggests shows that there was a change in the Australian inflation process around 2016. As a result, the trend in core inflation moved from ~2.5%yoy between 2010 and 2015 to 1.6%yoy from 2016.

If you look closely, you can see that the inflation trend was stable at around 2.5% from 1991 to 2005. There was a break higher for the mining boom, and then Gov Stevens returned the trend to ~2.5%yoy following the GFC (there's no real difference between the pre and post GFC trends). Then the trend in inflation broke lower at the end of 2015.

At first, it seems convenient for Gov Lowe that the estimated structural break is at the slightly before he took over from Gov Stevens, it’s not the ‘free pass’ that it might seem. Without getting too technical, you need a fairly long period of different inflation outcomes for the method to identify a structural break. If core inflation had returned to 2.5% any time before 2020, the method that I’m using would not have identified a structural break lower of inflation around this time (though the mean from 2010 would have been a bit lower).

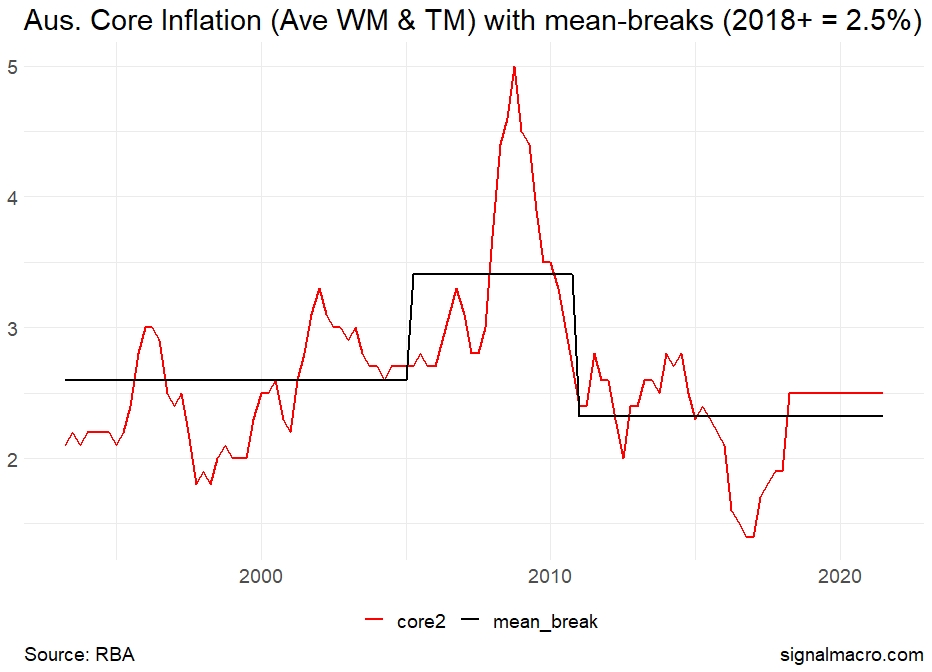

Lowe took over in September 2016, so (given the lags in monetary policy) he’s responsible for inflation from 2018. If we re-run the breaks-analysis assuming 2.5% core CPI from 2018, the post GFC trend of inflation declines to ~2.3%. This is a bit below target, but not significantly different to the pre-GFC trend of ~2.5%. In practice, you’d probably say that the trend of inflation in the pre-mining boom and post-mining boom periods were around the mid-point of the target band, and that there was a period of higher inflation during the massive term of trade boom. It seems okay to have overshot in that period.

However that’s not what happened. Instead, inflation remained low and so the trend of inflation moved down.

A review of the RBA would bump into this fact almost immediately. It would have to conclude that something happened to the inflation process in the middle of the last decade. It would have to note that the structural break occurred around the time that Gov Lowe took over running the RBA.

It may not conclude that it was Lowe's fault -- but it would be uncomfortable.

Did something unique happen in Australia?

Gov Lowe’s initial contribution as Governor of the RBA was to elevate the status of financial stability and dimmish the importance of the inflation target. Not that he used those terms: he emphasised the flexible, medium term, nature of the inflation target. While this may represent a type of continuity, I’m pretty sure that even Gov Lowe would agree that the inflation target became a bit more flexible, and a bit more medium term, under his governorship.

Lowe’s re-negotiation of the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, in 2016 was the means by which this was achieved. In that document financial stability was moved into the monetary policy part of the agreement and the emphasis on the flexibility of the inflation target was increased (the words ‘flexible medium-term inflation target’ didn’t appear in the prior SCMP).

This change was justified by a novel emphasis on the (previously little-mentioned) third target in the RBA act, the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia.

Lowe’s basic insight is that monetary policy works via household balances sheets and house prices. It follows that there may be costs, in terms of long term economic fragility, to rushing things. Lowe used exactly this trade-off when explaining the change to the House of Reps. He said they had come to the view that “a very quick return of inflation to the two to three per cent range, at the cost of a material deterioration in the health of private sector balance sheets, is unlikely to be in the public interest, so the revised drafting recognises that the inflation target is pursued in the context of the bank’s broader objectives, including financial stability. That is the monetary policy framework.”

Lowe started marketing the new framework from the moment he took over. It was the main subject of his opening statement to the House of Reps Standing Committee on Economics (22 Sep), and his first speech as Governor, Inflation and Monetary Policy (Oct 2016).

This was a surprise to markets at the time. When Lowe took over as Governor on 18 Sep 2016, the market had expected the RBA to continue easing to boost inflation (Stephens has delivered -50bps to 1.5% in May and August 2016). Instead, the Lowe RBA stopped. The Lowe RBA then delivered three years of unchanged rates and too-low inflation. The test for easing became ‘progress toward goals’. The message was that there was little harm from inflation that was around (or a bit below) 2%; and that the RBA would prefer to avoid risks that came with trying to rush inflation back to target.

As part of this, Lowe started talking about two-point-something inflation (consistent with inflation being between the 2% to 3% target range). And the market started to think that 2.5% was no longer the target.

The problem with the course of action is that there are also costs to inflation undershoots. We never got back to target, and then we had a big shock, so inflation expectations started to drift lower. Most people don’t know what inflation is, and don’t know what the RBA’s target is – but they get a feel for what’s going on. And their feel for what’s going on is some weighted average of their recent experience.

If you run the same statistical break-point tests over the union official and market (break-even) inflation expectations, you find that there’s a similarly located structural break around 2015. And the breaks could have been avoided if inflation went back up to 2010 levels.

Given this, there's a strong case that inflation expectations would have been higher if Gov Lowe's RBA had a narrower focus on inflation, and continued to had cut rates in 2016/17.

It's common to claim that inflation expectations remain 'anchored', despite this period of low inflation, but I don't share that view.

The decline of union official inflation expectations is particularly problematic, given the importance of wages in driving medium term inflation outcomes. A major part of what union officials do is argue for higher wages, so if they don’t expect much inflation it’s hard to see wages speeding up and driving inflation. Finally, I don’t put much stock in the recent increase of union inflation expectations — it’s almost certainly just a bit of temporary, catchup, price pressure.

Conclusion

A review of the RBA would probably identify Lowe’s softer commitment to 2.5% inflation and the tension between the inflation mandate and the financial stability mandate as factors pushing inflation down.

My guess is that Lowe was getting ahead of the OECD’s call for a review (a review almost certain given bi-partisan support) by making a firm commitment to get inflation back to the mid-point of the target range before hiking and by pushing back on the financial stability (house price) argument for raising rates, in his speech Delta, the Economy, and Monetary Policy (read the day before the OECD report was published).

A looming review into the RBA's performance makes any action that might threaten the attainment of the target unlikely. A mistake due to another early tightening would be extremely unhelpful for the institution. It would probably revive the push for an external appointment to replace Gov Lowe when his term ends.

All this makes it very unlikely that Gov Lowe will lift rates before his term ends in 2023. Indeed, based on current numbers I doubt the RBA will get close to 2.5% before 2025.

2 topics

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...