David beats Goliath: A story of private equity

“I’ve got liquidity problems.”

This phrase has become a badge of honour among large-cap fund managers; a self-deprecating gloat that they’ve outgrown the market and become a victim of their own success.

While liquidity problems do infer historical success at fundraising or growing capital, they don’t portend future success. Liquidity pressures prevent one from achieving the asset allocation they would otherwise intend, and realising the entry and exit prices they would otherwise deserve.

Within the private equity space, Australia’s superannuation funds and large private equity funds are just as exposed to liquidity problems - albeit with different nuances. And it’s costing them in opportunities and performance.

In this piece, we run through the problem facing large superannuation and private equity funds, before highlighting the performance they’re missing out on in the small and middle markets – just the part of the market Schroders Capital plays.

Awash with cash

Australia’s superannuation industry controls an enormous pool of capital. As of September 2023, total superannuation assets totalled $3.5 trillion, with $114 billion of it invested in unlisted equities.(1)

It’s also an increasingly consolidated market. After a raft of M&A in recent years, the five largest funds now command roughly a third of the industry’s funds under management.

So much capital controlled by so few funds invariably leads to gigantic pools of capital.

Large super funds have such huge amounts of capital to invest - and are continuously attracting new capital, both through increasing compulsory superannuation contributions and through compounded returns – that they have been forced to write large tickets to put the capital to work. This means generally in private equity they are restricted to the large and mega cap buyout space which can absorb larger tickets into mega funds.

Additionally, given private equity tends to attract a c. 2% management fee and 20% performance fee, many superannuation funds are trying to reign in this cost by accessing co-investments, where they invest alongside the manager directly into the company and try to negotiate this company access for “free”. This dilutes the overall costs of accessing fund and direct investments, however again – if a superannuation investment team is going to spend days, weeks or months undertaking the required due diligence to invest directly, they will need to do so at a size that justifies their time.

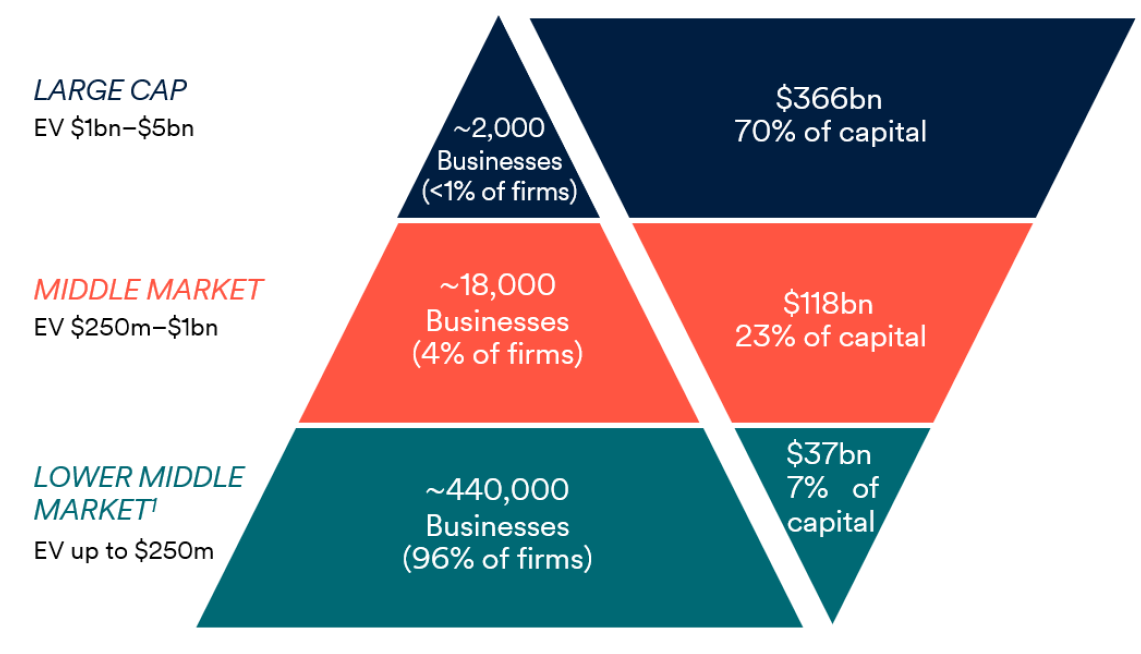

Figure 1 – Deal size vs. opportunity

Source: National Center for Middle Markets. Burgiss, including all North American buyouts. Lower Middle Market is defined by funds whose sizes are between $50m–$500m. Middle Market is defined by funds whose sizes are between $501m–$2bn. Large Cap is defined by funds whose sizes are greater than $2bn.

Large private equity firms face similar problems. Like the big super funds, they have huge amounts of capital to deploy and too few resources to filter opportunities outside the large and mega-cap buyout space. So that’s where they go, and it’s costing them.

Large-cap ≠ large performance

There’s a misguided belief in some corners that, as a general rule, large caps deliver superior relative return over small and mid-caps.

That’s simply not the case.

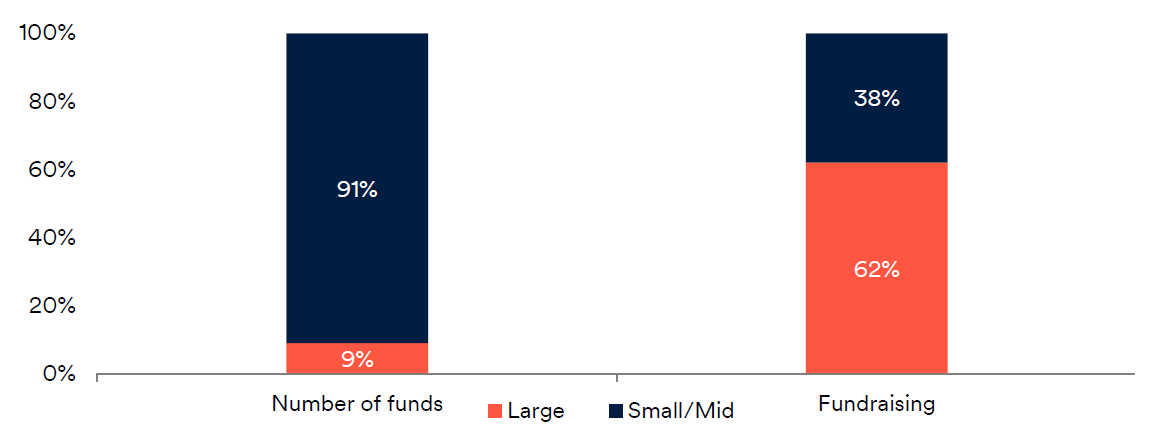

According to Preqin data from 2010 to 2022, fundraising among large-cap funds grew by 10.7x while deal flow grew at 3.6x. That despite there being 40x more small and mid-funds in the market than large funds.

Figure 2 – Private equity buyout fundraising 2010 - 2022

Source: Preqin, Schroders Capital, 2023. Fund size classification: Small: fund size below US$500m; Medium: fund size between US$500m and US$2000m; Large: fund size above US$2000m. Fund of funds and single asset funds excluded.

This imbalance between capital supply and demand pushes up entry multiples, thereby compressing overall growth multiples.

Small and mid-sized funds, by contrast, have seen deal flow growth of 4.2x against fundraising growth of 2.9x. Lower capital supply coupled with relatively higher demand for capital encourages lower entry multiples.

These lower entry prices make a big difference. Expressed as EV/EBITDA multiples, it translates to a ~5-6x discount.(2)

In short, we buy companies at low entry multiples while they’re small or mid-sized, and sell them upmarket when they’re large caps.

Schroders Capital’s advantage

Ultimately, performance is what really matters – and we’ve got the receipts.

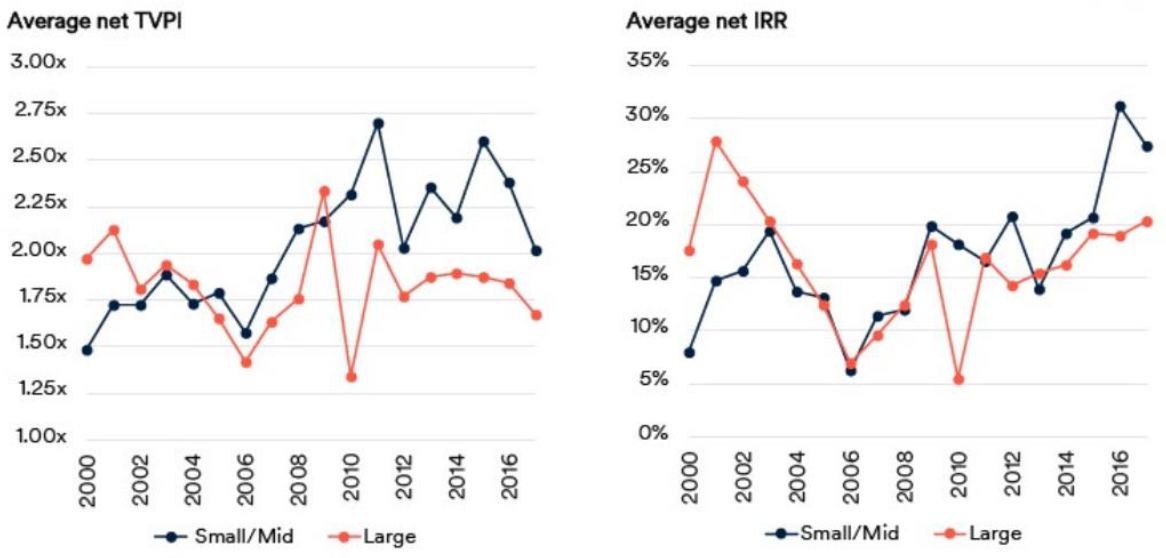

On average, small and mid-sized private equity managers – of which Schroders Capital is one – have outperformed their large private equity peers both on a net total value paid in (TVPI) basis for vintages after 2005 and on a net internal rate of return (IRR) basis for vintages after 2009.

Figure 3 – Average net TVPI and IRR by fund vintage

Source: Preqin, Schroders Capital, 2023. Performance numbers are net to investors. Fund size classification: Small: fund size below $500m; Medium: fund size between $500m and $2000m; Large: fund size above $2000m. Includes all strategies (VC, growth, buyout) excluding fund of funds, single asset funds.

This trend can also be seen across different geographic regions and investment strategies. Between 2000 and 2017 across Asia, North America and Europe, small and mid-sized funds delivered higher net returns than large funds, while small and mid-venture, growth and buyout funds also outperformed their large counterparts.

All this is not to say that liquidity isn’t a factor in the small and middle markets – it is.

2021 was a particularly heady year with a high level of deal activity. So the subsequent drop in activity is an expected correction.

That said, tighter liquidity conditions have been felt predominantly at the upper end of town, as IPOs dried up in 2023. But we don’t rely on IPOs to exit our positions. We tend to sell our businesses to other funds or corporations, and while exits here are down, they’re not at levels that make us uncomfortable.

In summary

Any private equity fund that is well managed, with the right portfolio of investments, can generate attractive returns. But large size is not a guarantee of performance in and of itself. Just the opposite.

As the data shows, all things being equal, funds that buy small and mid-cap companies statistically perform better than their large-cap peers thanks to a greater number of opportunities, lower entry multiples and a longer runway for growth. Just how we at Schroders Capital like it.

A broad opportunity set to help you achieve specific goals

Private assets and alternatives are a vast universe comprising a diverse range of asset classes that can cater for investors of all types. Whether it’s private equity, hedge funds, infrastructure or real estate, there’s plenty of potential to build a strong and diverse portfolio, using multiple strategies to meet long-term goals.

1 fund mentioned