Does Growth Matter In Emerging Markets?

Dalton Investments

Many of the appeals of investing in emerging markets are rooted in higher economic growth. But, it is important to understand that growth only plays a marginal role in driving returns, its influence dwarfed by the the impact of value and momentum. This understanding is particularly relevant when you consider the challenging environment value-oriented investors have endured in the emerging markets over the past year. Further amplified for those that care about alignments of interest and corporate governance. The material outperformance of market segments traditionally plagued with governance risk has dominated the performance tables, notably internet securities and energy-related stocks. This, in turn, has led many investors to think about how they invest in emerging markets.

It is never a good feeling to either lose money or trail benchmark indices over an extended period. Such environments, predictably, force a degree of introspection and present an opportunity to revisit elements of the investment process, retest their integrity and challenge the basis of stock selection criteria.

I think it's very important to have a feedback loop, where you're constantly thinking about what you've done and how you could be doing it better.

Elon Musk

While self-examination is important, we absolutely do not want to style drift to simply engineer our performance to be closer to the crowd. The foundations of our investment process are steeped in a wide body of academic and empirical evidence, but it is important to identify if the process is exposing us to unintended weaknesses. This, in turn, may be an opportunity to make incremental enhancements if they are value accretive.

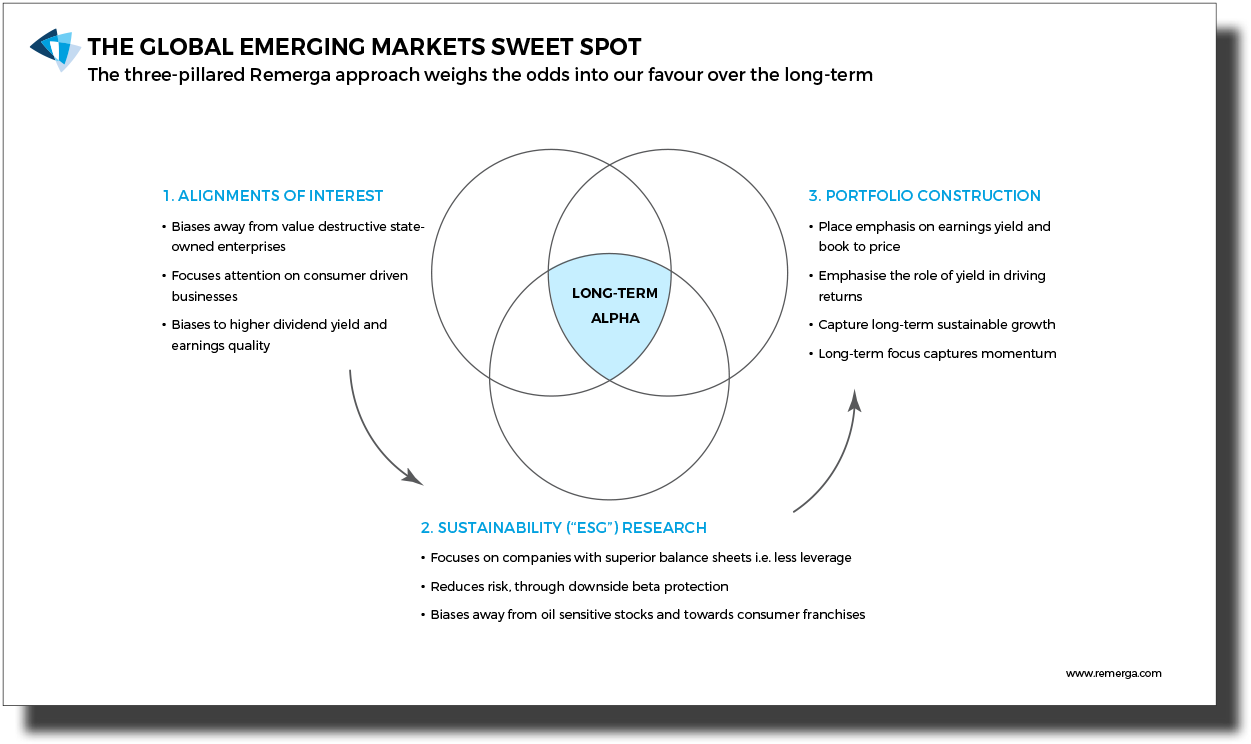

The Remerga investment process is anchored by the triumvirate of alignments of interest, sustainability research and value based portfolio construction guidelines. It is true that the only valuable investment strategies are those that are repeatable and strictly implemented. The evidence points to the fact that the anchors of our investment process offer repeatable long-term excess returns, provided we strictly adhere to it. If the key drivers of our return series breakdown and stop working, the investment process will be rendered obsolete if it does not evolve. From time-to-time, it pays to re-examine the foundations of your investment process and re-test whether the original hypothesis maintains its original efficacy. In this thought piece, we have taken to analysing the key risk factors driving returns in emerging markets and relate this back to our three-pillared investment discipline.

1. ALIGNMENTS OF INTEREST

Focusing on investment opportunities where it pays to be a minority shareholder provides the backbone of our investment discipline. Emphasising shareholder structures, the long-term capital discipline of the company and how capital flows through to minority shareholders, leads to inevitable intended biases. Most notably, there is an active avoidance of state-controlled companies and a preponderance to favour more consumer driven and family-controlled companies. In turn, paying close attention to dividends and cash generation over time results in a bias towards higher dividend yield stocks where the quality of earnings is superior.

2. SUSTAINABILITY (“ESG”) RESEARCH

A wide-body of academic evidence supports a long-term focus on superior ESG companies. By the end of 2012 over 125 global studies had been conducted on the merits of ESG focused investing. A number of these have been crucial in shaping the Remerga investment process. Of the 125 global studies, 100% agreed that companies with high ESG ratings have lower costs of capital. More recently, Harvard Business School has published research that demonstrates that sustainability focused companies outperform their counterparts both in market returns and financial performance. Through focusing on companies that sit in this category, it is evident that the portfolio exhibits less embedded leverage in its portfolio positions and by default you enjoy a portfolio with less beta and greater downside beta protection. Both of these are accretive to long-term returns. It is also worth noting that by biasing naturally away from oil sensitive stocks and towards consumer franchises, you enhance the earnings quality of your investment portfolio.

3. FUNDAMENTALS

It is well known that price momentum is an integral driver of market returns, both in the developed and emerging markets. It is our view that momentum is hard to capture in the emerging markets, given the higher costs of transacting and higher turnover that stems from purer momentum strategies. However, you can capture momentum successfully in your investment portfolio through an approach that does the direct opposite. An infrequently traded portfolio that holds positions over the long-term captures the momentum effect through the effective up-weighting of positively trending names while down-weighting those with negative momentum. It pays to be a long-term investor.

In addition, an emphasis on value pays over the long-term, as does capturing earnings quality and avoiding leverage. It will be surprising to many investors that growth does not materially drive returns in the emerging markets. However, we firmly believe that growth is only advantageous in the environment where the value is appealing. It is also worth noting that value offers the best returns per unit of risk. So, if you care about the permanent impairment of capital then emphasising value is of paramount importance.

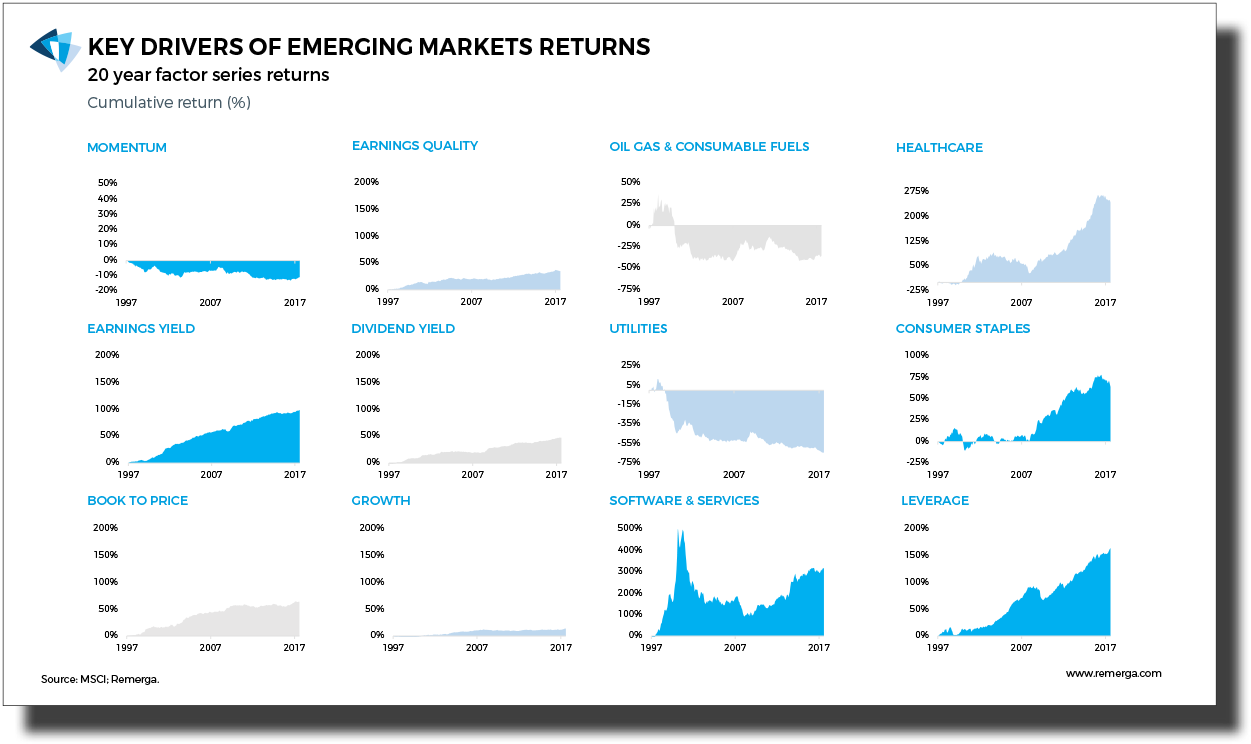

CHART 1: KEY DRIVERS OF EMERGING MARKETS RETURNS

The long-term evidence outlined in the charts above point towards the merits of the Remerga three-pillared investment approach. It pays not only to be long-term in orientation but the intended and long-term biases we target improve the odds of long-term success. When dealing with uncertainty it is vital to tilt the scales in your favour over time, and by design that is what an investment approach focused on alignments, sustainability and fundamentals achieve.

CHART 2: THE EMERGING MARKETS SWEET SPOT

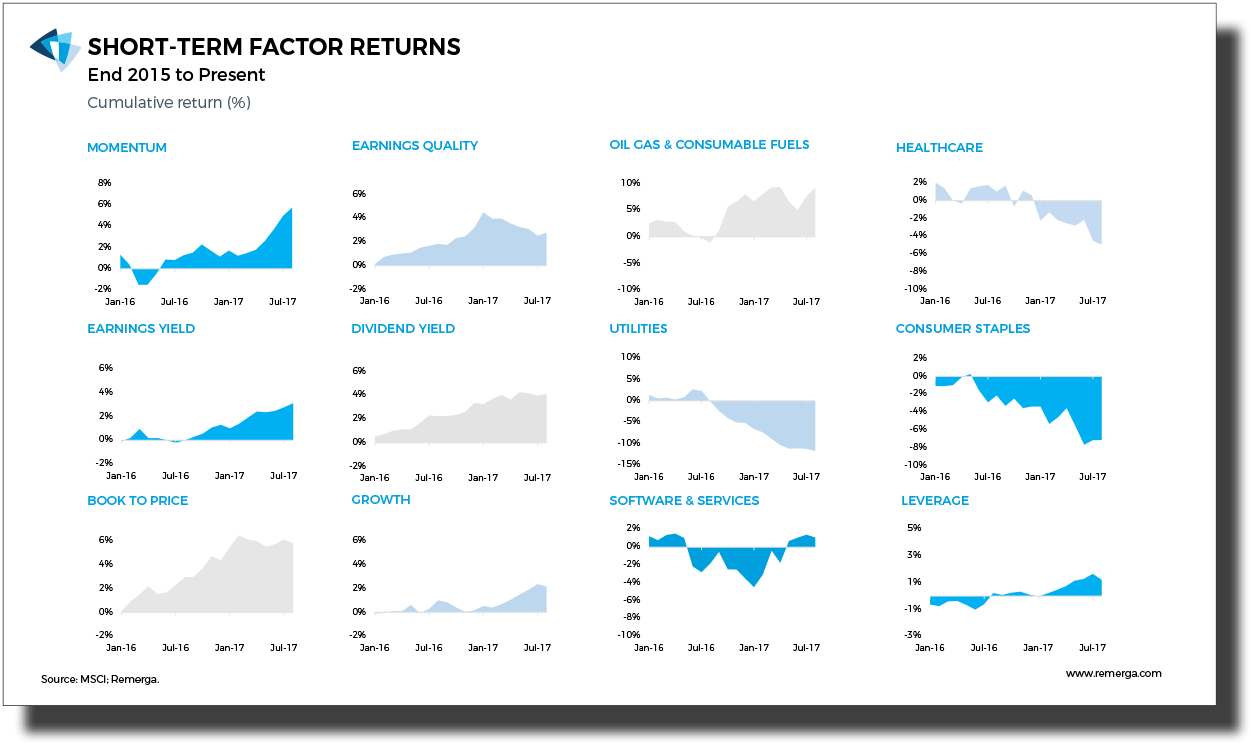

It is true, however, that adopting a disciplined investment process of this kind does not necessarily insulate your returns from the pervasive nature of the short-term factors driving markets. Consequently, we wanted to examine why our investment approach has not worked particularly well in the past 12 to 18 months. Examining the same set of factor returns since the start of 2016, it becomes clear why performance has struggled in the short-term.

CHART 3: SHORT-TERM FACTOR RETURNS

As we can see from the above, value has not worked well throughout 2017, particularly a bias towards price to book and dividend yield, while there has been no reward for earnings quality. This is supported by examining what has materially outperformed this year, namely Chinese internet stocks, where the earnings quality is mixed and multiples very high. Growth as a factor has also contributed an outsized return relative to what we have seen over the very long-term, reinforcing the role the technology has had in driving the market returns.

In addition, the evidence points to a strong rebound in oil and gas, a sector where we have a natural predisposition not to invest given the role of state-owned enterprises in the sector and the sustainability considerations. This, in turn, is exacerbated by the fact that the market has shied away from consumer-driven sectors, which have underperformed as a group, with the market strongly favouring software companies including index heavyweights Alibaba, Tencent and Naspers.

FINAL THOUGHTS

We are mindful of the dangers of conducting backward-looking analysis to validate the future direction of our investment strategy. Understanding the reasons why many of the characteristics identified in the analysis remain crucial drivers over the long-term is vital to the success of investing in emerging markets. Most notably, performance is inextricably linked to the price paid. In high growth economies, there is a tendency to witness commensurately high valuations, given that growth expectations are priced into assets. Unless the starting point is one of attractive valuations, investors will likely be disappointed. Moreover, in the emerging markets, investors need to be cognisant that the prevalence of ‘attractively-valued’ state-owned enterprises acts like a siren call towards an unappealing segment of the market. State-owned enterprises may warrant a discount, because of poorer returns and a misalignment of interests, and they may remain cheap or get cheaper indefinitely. Examining the cross-shareholding structures of chaebols in Korea or keiretsus in Japan demonstrates how a fundamental misalignment of interest to minority shareholders results in weak long-term returns and persistent value discounts. This is also further demonstrated by the long-term value destruction highlighted by the factor series returns of sectors heavily influenced by state companies.

We have noted in prior research that the reasons for wanting to avoid state-controlled companies includes the role incentives play in creating shareholder value, in that there are few incentives to create shareholder value. State-owned enterprises will remain a large component of the emerging markets index over the long-term. This stems from the vast number of enterprises in the key markets (e.g. 147,000 noted non-financial state-owned enterprises in China) and potential future index inclusions by MSCI, which have market structures largely comprised of state entities (e.g. Saudi Arabia). In addition, reform in centrally planned economies is a multi-decade process. A major ancillary benefit of positive reform is the ability for private companies to enter previously protected industries. It is likely that reform will be detrimental to many companies in specific industries that are protected by government granted monopolies e.g. banking, insurance, energy, telecom and airlines. Meanwhile, some companies will phase out capacity due to stricter regulations - especially those having small market shares and facing operational challenges in sectors such as coal, construction, chemicals and shipbuilding. Furthermore, as reform takes place we will see concentrated state ownership positions systematically reduced, which can lead to negative momentum and a stock overhang. The buyers are likely to be other private companies, which themselves are minority state-owned. This will result in the creation of complex cross-shareholding structures that lead to ineffectual management and governance, so over the long-term, the impact of reform in the state-owned enterprise sector is potentially negative for the performance of those assets.

The role of population changes and long-term urbanisation trends will also underpin the importance of consumer-driven sectors in emerging economies. Having a long-term bias towards these areas is valuable but always with the caveat that the price paid for such investments must be attractive. Finally, the role that a focus on sustainability or ESG plays is important. As the wide body of academic evidence demonstrates, there is no punitive effect on returns through a focus on ESG. Without limiting your returns, you materially reduce the risk in inherent in your investments, particularly when examining the cost of capital for those companies with better practices and lower use of debt on the balance sheet.

The one clear area of potential weakness in the process we adopt is its current lack of exposure to technology. This position is driven from the bottom up and a direct consequence of the due diligence we conduct on governance practices, coupled with the very high multiples. We wrote about this extensively in last quarter’s research piece Long Live the Unicorn. Should the alignments and governance practices develop in favour of minority owners and assuming attractive fundamentals, we would be happy to own the sector more widely. The same could be said about China. We are unapologetic about this, as we noted earlier valuable investment strategies are those that are repeatable and strictly implemented.

Like Elon Musk, we believe in feedback loops. At regular intervals, we need to continually test the efficacy of our investment discipline but are aware of the need to avoid style drift. Howard Marks, the famous founder of Oaktree Capital, pondered in his book The Most Important Thing that to be a successful investor you need to engage in second level thinking. This form of thinking requires a great deal more effort and thought than first level thinking. A second level thinker needs to think about the world and each investment in multiple dimensions before weighing these scenarios within a probabilistic framework. We believe our process achieves this and crucially weighs the odds in our favour.

Craig is passionate about building investment portfolios with a deep emphasis on corporate governance and sustainability in the emerging markets and is a strong advocate for uprooting the status quo.

Expertise

No areas of expertise

Craig is passionate about building investment portfolios with a deep emphasis on corporate governance and sustainability in the emerging markets and is a strong advocate for uprooting the status quo.

Expertise

No areas of expertise