How would the market react to a US default?

Spreads of credit default swaps (CDS) on US sovereign risk have moved materially higher in the past few weeks. Is a US default a real possibility?

We believe a US default is a very low probability event. The only time the US “technically” defaulted was in 1979 when a word processing backlog resulted in the delayed payment of maturing US Treasury (UST) bills. Moreover, Congress has raised the debt ceiling 78 times since 1960; 49 of these under a Republican president and 29 under a Democratic president.1 All that stated, markets are bracing for the possibility of a standoff that lasts deep into the 11th hour, an outcome that harks back to 2011, 2013 and 2021. In each of those three episodes, Congress averted a default, but not without roiling financial markets. Today’s supercharged political partisanship—with Republicans controlling the House of Representatives and Democrats controlling the Senate and the White House—has only served to heighten market concerns that we might not see a political compromise on the debt ceiling. This fear partially explains the recent spike in US CDS spreads.

Bear in mind, though, that the CDS market for sovereign risk mostly comprises emerging market countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Russia and Turkey. The US CDS market is relatively new and much smaller in size, especially when compared to that of USTs. For instance, on a net basis, the size of outstanding US CDS contracts is estimated at $5 billion versus the estimated size of $73 billion for the May 15, 2050 UST bond,2 which are the cheapest-to-deliver bonds on those contracts. The illiquidity of the US CDS market (with only non-US banks allowed to make markets on these contracts) and the fact that the cheapest-to-deliver bonds are much more heavily discounted today help to explain why US CDS spreads across various tenors have moved materially higher since the beginning of the year.3 For instance, 1-year US CDS spreads have widened out to 155 basis points (bps) as of May 5, 2023 versus 18 bps at December 31, 2022. Spreads on 3- and 5-year US CDS spreads have widened out by 70 bps and 42 bps, respectively, during the same time period.4

What is the “x-date” and what happens if the debt ceiling isn’t raised by then?

As context, the US technically hit its $31.4 trillion debt limit on January 19,5 which means that the government cannot technically issue any new debt. Since then, the Treasury has been using various “extraordinary” accounting measures to pay the government’s obligations in full and on time. Market pundits are now trying to estimate the “x-date,” which is the date when the US runs out of funds to meet its obligations, taking into account the use of extraordinary measures. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s recent comments suggesting that June 1 could be the x-date unnerved markets (given the Congressional Budget Office’s earlier estimates that extraordinary measures would likely be exhausted sometime between July and September), but it’s important to note that the x-date is highly dependent on the timing and amount of incoming federal tax receipts. Estimating the x-date is particularly complex this year due to the delay in the tax-filing deadline for Californians impacted by winter storms.

If the debt ceiling isn’t raised by the x-date, we expect the Federal Reserve (Fed), which acts as the fiscal agent for the Treasury, to follow the blueprint it crafted in 2011. The aim of that blueprint was to “prioritize” interest and principal payments on federal securities over Social Security payments, salaries for federal civilian employees, military benefits, unemployment insurance as well as other obligations.6 The Fed also has contingency plans in place (e.g., via money market operations) to deal with market disruptions in the event of an imminent default. The Treasury itself could take other forms of action to avoid a default by raising cash through either the minting of a special large-denomination coin (which would be deposited at the Fed with the funds used to pay the government’s obligations until the debt ceiling is raised), selling gold or by issuing new debt via Section 4 of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution—the Public Debt Clause explicitly states that “the validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law … shall not be questioned.” However, we would emphasize that pursuing such alternatives carries unknown political and economic costs.

How would the market and rating agencies react to a US default?

We believe a default on any Treasury payment would precipitate a severe market reaction with market volatility approaching or even exceeding levels observed during the 2008 global financial crisis. In such a scenario, we would anticipate that Congress would move quickly to resolve the situation; however, a default would call the relative economic and political stability of the US into question.

The impact of such an event on UST yields would be varied but ultimately we expect yields would move lower. For instance, if a default were to trigger a rating downgrade, there could be some forced sellers which would push UST yields higher. However, the confidence hit to the US economy (and its ripple effect across global financial markets) as well as flight-to-quality dynamics would, in our view, overwhelm any selling activity and consequently push UST yields lower.

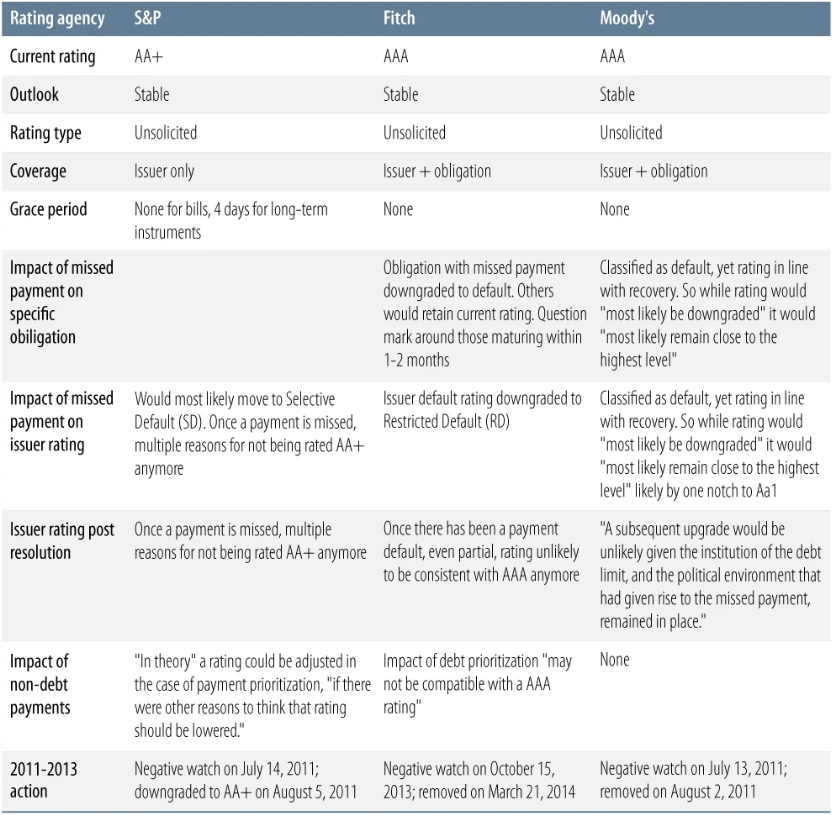

The following table summarizes each of the rating agencies’ views regarding what would happen in the event that the US Treasury misses an interest payment.

Exhibit 1: US Ratings Summary

Sources: S&P, Fitch, Moody’s, Morgan Stanley Research. As of February 28, 2023.

Learn more

Western Asset is a globally integrated fixed-income specialist with an ability to combine global insights with local market opportunities. Find out more here