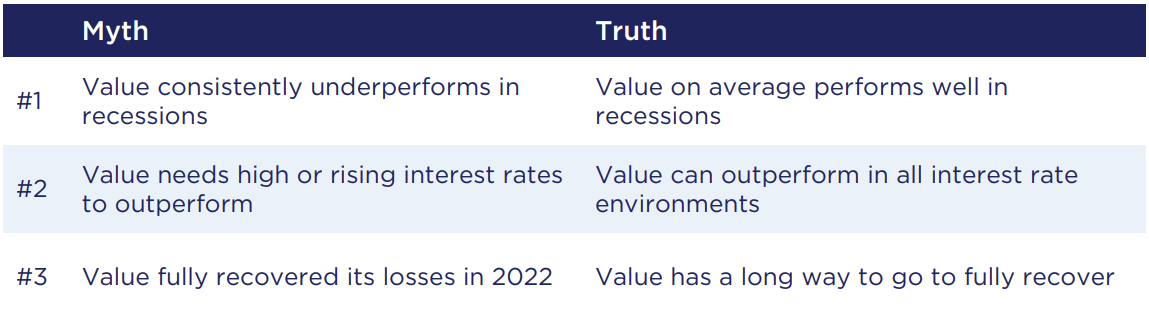

Investing myths debunked

Growth shares have outperformed strongly in recent times. Between 2007 and 2021 the MSCI World Growth Index returned an incredible 11% p.a. (in AUD terms), beating the Value Index by about 4.5% p.a. The exciting companies behind that stellar performance, like Atlassian and Afterpay, left their more boring, ‘old economy’ counterparts in their wake.

Charlie Munger once said, “all intelligent investing is value investing – acquiring more than you are paying for”. But in recent years the market seemed much more interested in what it got, than what it paid.

Value investing, in the doldrums for most of the last 15 years, staged a modest comeback in 2022. The MSCI World Value Index recovered about a third of its 2006-2021 losses relative to the equivalent Growth Index, and now asset allocators are reassessing and debating the role value investing plays in diversifying portfolios.

As the growth vs. value debate intensifies, we seek to debunk three common myths about value investing with hard data and considered analysis.

Myth #1: Value consistently underperforms in recessions

A common misconception is that value shares consistently underperform in recessions because they are more cyclical.

The most recent two recessions, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and Covid-19, appear to reinforce this notion. In the GFC, banks were ground zero for excess mortgage debts. As banks (and other financials) tend to trade at low multiples, they get disproportionately represented in value indices, meaning the value index also tends to suffer when banks suffer. In the Covid19 recession, a global pandemic forced the globe to stay home, driving technology shares like Zoom and TikTok, and the growth indices to which they belong, to dizzying heights.

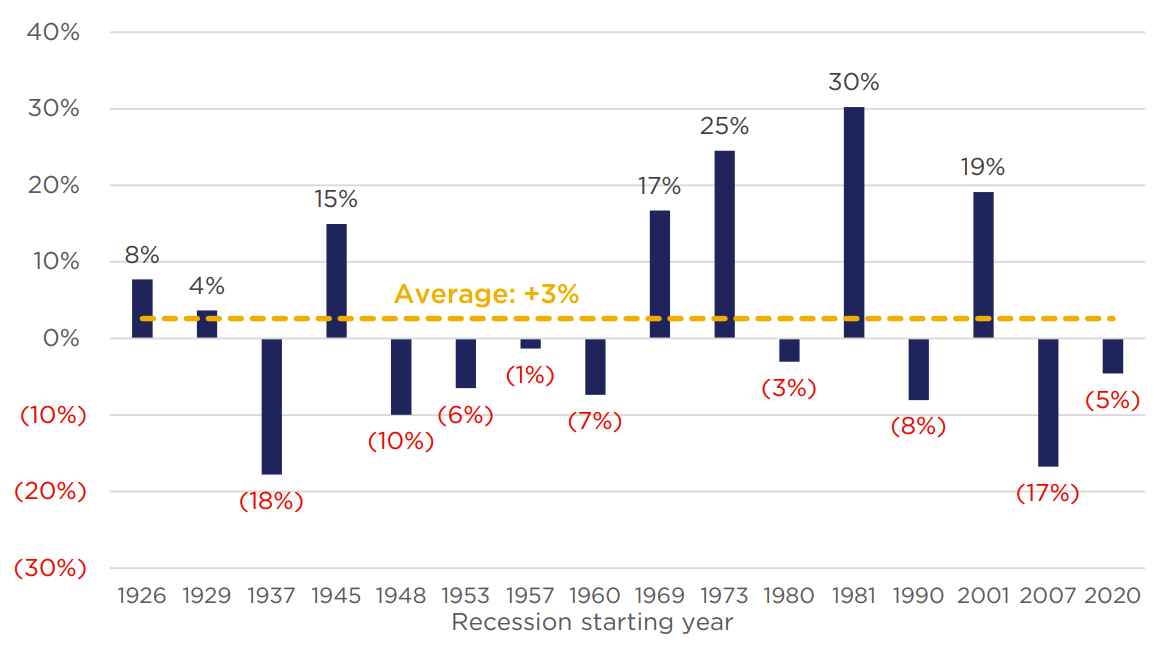

In these two recessions, value shares underperformed their growth counterparts for sound, fundamental reasons. But not every recession is like that. As shown in the chart below, on average, value shares have outperformed growth in recessions over the last 100 years – often meaningfully so.

For example, value beat growth by a wide margin when tighter monetary policy and rising interest rates triggered a recession in 1969. The energy crisis in 1981 saw value shares win, too. And when the dotcom bubble burst in 2001, value shares went on a historic 5-year run. Investors now face what might be the most anticipated recession in recent time but take this with a grain of salt; investors are also notoriously bad at forecasting recessions. If, against the odds, the punters get this call right, they also need to anticipate the type of recession it will be, because that matters just as much when assessing value relative to growth. And, as illustrated below, value can outperform in a variety of recession types.

It’s important to keep a long-term perspective and remember that, on average, value has outperformed growth in recessionary environments.

Outperformance of Value vs. Growth in US recessions

Source: Kenneth French, Center for Research in Security Prices, The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Orbis. Recessions as defined by the NBER. Value vs. Growth calculated as return of the Value (high book-to-price) portfolio less the Growth (low-bookto-price) portfolio, using monthly returns in US dollars from July 1926 to December 2022 of US large- and small- cap shares. Performance is calculated with a lead of 3 months from the indicated ‘Peak’, which is classified by the NBER as the business cycle peak.

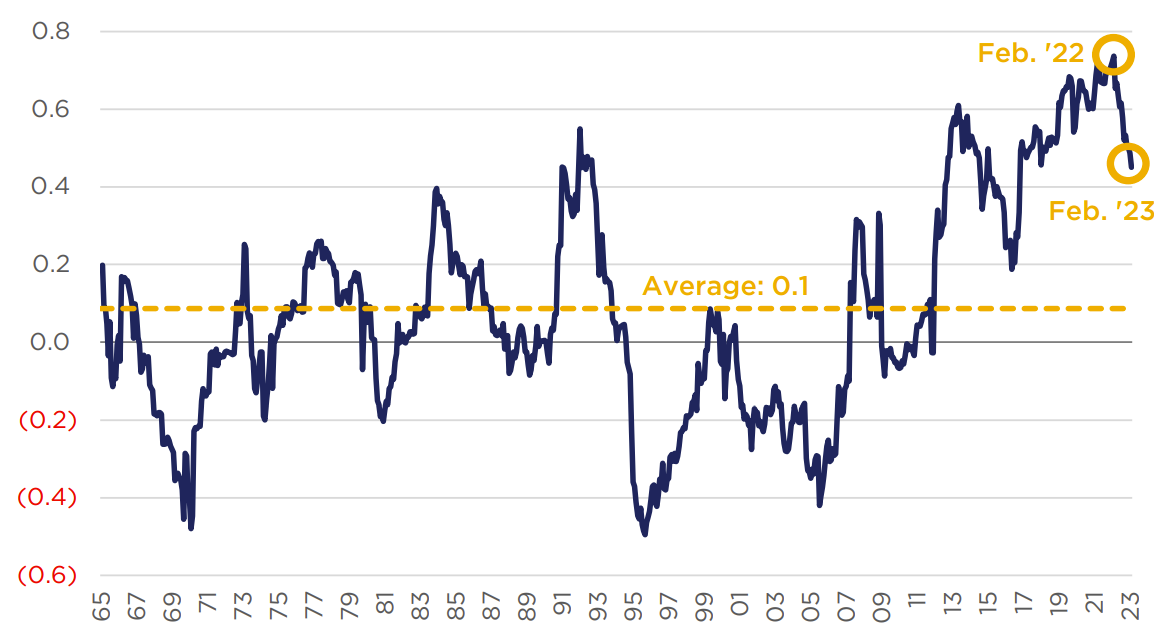

Myth #2: Value needs high or rising interest rates to outperform

More recently, investors have been quick to point out the correlation between interest rates and the performance of value, which has indeed been stronger than usual in the post-GFC era. But over the long run there’s little connection between the two. As illustrated in the chart below, the average correlation between the outperformance of value vs. growth and changes in interest rates since 1965 is barely above zero. And while the two have indeed been more correlated over the last decade, that connection has more recently weakened and the correlation is heading back toward its long-term average, which is close to zero.

Correlation between outperformance of value and changes in interest rates (US)

Source: Kenneth French, Center for Research in Security Prices, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Orbis. Correlation measured over trailing 36-month periods between changes in 10-year US Treasury rates and Value vs. Growth, calculated as return of the Value (high book-to-price) portfolio less the Growth (low-book-to-price) portfolio of US large- and small- cap shares.

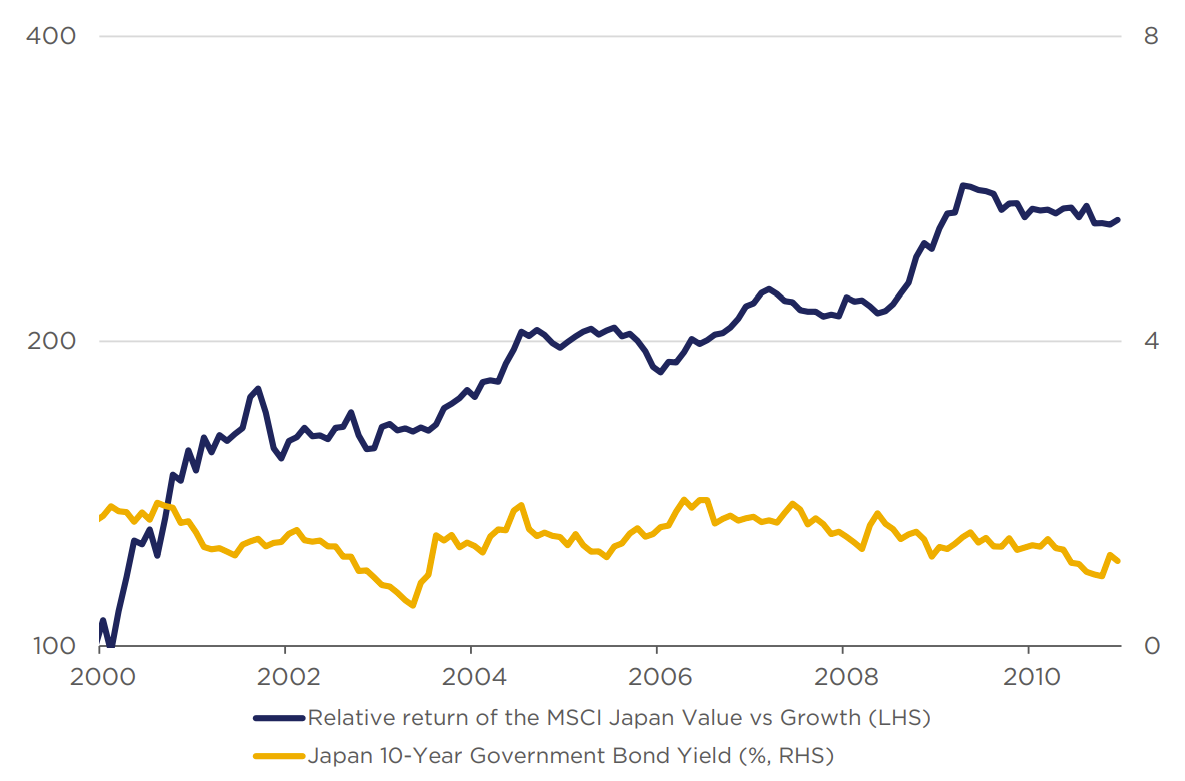

If changes in interest rates don’t matter for value, what about the level of interest rates (i.e. whether they’re high or low)? That, too, exhibits almost no relationship over the long term, with Japan a prime example. Consistently low interest rates might be new to the rest of the world, but in Japan rates fell to extremely low levels in the 2000s, with 10-year government bonds yielding less than 2% during that period. Despite these persistently low rates, value outperformed growth by over 9% p.a. between 2000 and 2010.

The following charts illustrate that value can outperform in all interest rate environments: rising or falling, high or low. This serves as a useful reminder that value outperforms not because inflation or interest rates rise or fall, but because human psychology means investors sometimes become overly fearful and make irrational decisions to sell their shares at excessively-low prices.

Value outperformed in Japan in a low interest rate decade

Source: Datastream, Orbis.

Myth #3: Value fully recovered its losses in 2022

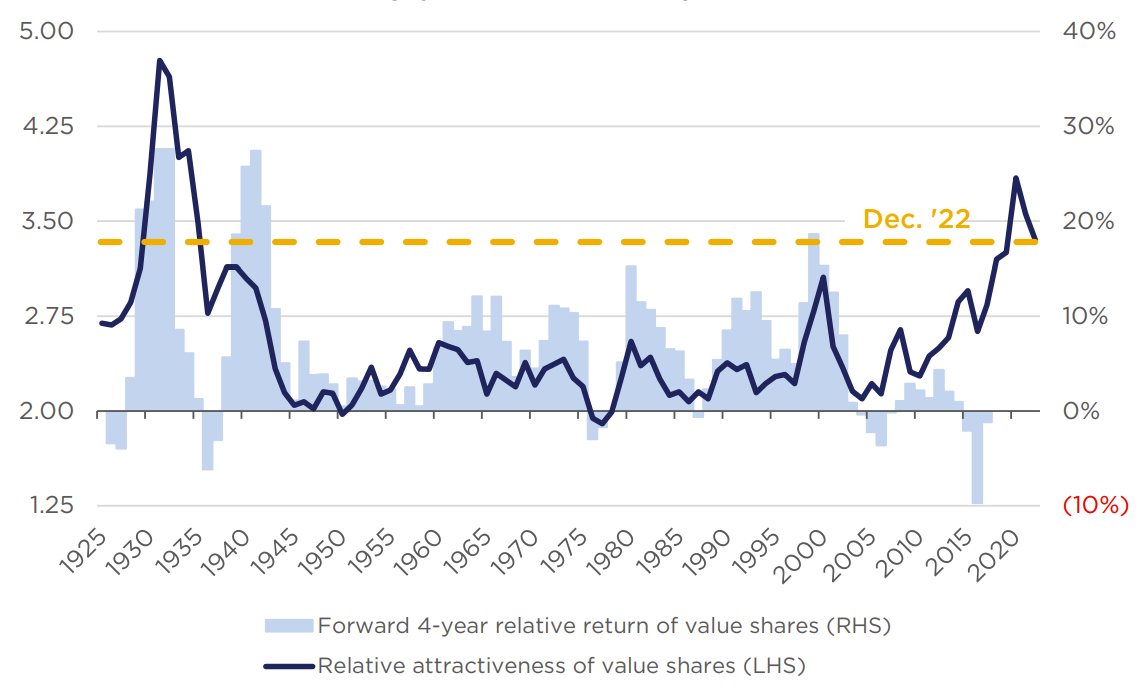

Value shares, by definition, are cheaper than their growth counterparts when evaluated using simple metrics like price-to-earnings or price-to-book. But the discount investors get on value shares is not fixed. That difference – the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ as the market sees them – varies over time. This is partly why Orbis adopts a flexible approach to value investing, driven by intrinsic value rather than simply buying shares with low multiples.

The valuation gap is the best indicator of the relative attractiveness of values shares compared to growth. As illustrated in the chart below, over the last 100 years value shares were cheapest (versus growth shares) during the 1930s Great Depression, followed by the market trough of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the gap today remains excessively wide – wider than even the peak of the dotcom bubble.

Whilst this dynamic started to reverse in 2022, value shares still have a long way to go before they normalise versus growth.

Valuation gaps remain extremely wide in the US

Source: Kenneth French, Center for Research in Security Prices, Refinitiv, Orbis. Value (growth) shares are those in the cheapest (richest) half of the market on a price-to-book basis. Relative attractiveness is based on the book-to-price ratio of the relevant market segments. 2022 relative attractiveness calculated by Orbis based on NYSE listed stocks in the Russell 3000 Index. Statistics are compiled from an internal research database and are subject to subsequent revision due to changes in methodology or data cleaning. Relative return series calculated from the annual return of US high book-to-price portfolio less the return of US low-book-to-price portfolio, large- and small- cap shares.

So what?

Three common myths about value investing can be replaced with three more useful truths: value on average performs well in recessions, value can outperform in all interest rate environments, and value has a long way to go to fully recover.

Armed with this knowledge, investors should consider reviewing the existing style allocations of client portfolios, assess their existing value managers for any signs of style drift, and ensure their value manager mix blends well to boost the opportunity for idiosyncratic alpha in client portfolios.