President Trump’s policies and the equity risk premium – the good, the bad and the ugly

Trump’s policy making has led to lots of volatility in shares – with record highs in February then plunging 14 to 19% on the back of tariff worries into and after his Liberation Day “reciprocal tariff” announcement, only to recover around three quarters of their falls.

In fact, US shares are now down just 4% from their record high and Australian shares are down just 3%. Tariffs have been the main driver of this volatility, but it has come with disruptive pronouncements with respect to the US government, legal system, immigrants, the Fed, US allies, DEI and attacks on the media.

Quite clearly this has had a short-term impact on investment markets, but could it also have a longer impact? This note looks as the good, the bad and the ugly of Trump’s key policies from an investment perspective.

Tariff mayhem, but Trump to the rescue!

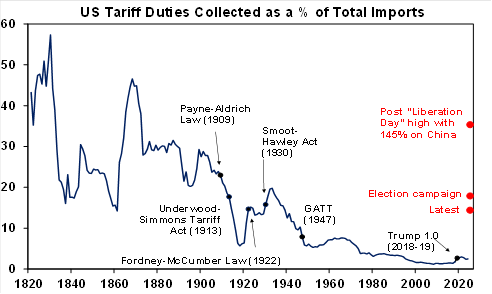

At one point after Trump’s Liberation Day tariff announcements, when the US and China engaged in levying tit for tat tariffs on each other’s goods, the implied average tariff on goods going into the US rose to over 30%. This was up from just 2.7% at the start of the year, way above levels that Trump campaigned on and at a level not seen since the late 1800s.

Source: US ITC, EvercoreISI, AMP

Fortunately, since then the trade war has been dialled down substantially. Various sectoral tariffs remain, such as on steel, aluminium and autos. But Trump has reduced the prohibitive “reciprocal” and retaliatory tariffs on China from 125% to 10%. This has reduced its total tariff from 145% to 30% (or 41% if the existing tariffs are allowed for).

The US also relaxed tariffs on Canada & Mexico, provided some exemptions, and wound back the general “reciprocal tariff” on all other countries to 10%. This has seen the average tariff on goods coming into the US fall back to around 14%.

The good

There is lots of good news in Trump’s back down which is why share markets, the US dollar and Bitcoin have celebrated.

First, the worst-case economic scenario looks to have been averted at least for now. Lower tariffs mean less disruption to global trade and hence economic growth. The risk of recession in the US has probably dropped back from near 50% to around 35-40% and so the blow to global and Australian growth probably won’t be as bad as feared.

Second, if Trump was going to do the market negative things, i.e. the “detox” in terms of tariffs and the DOGE cuts, it made sense to do it early to allow time for recovery ahead of the mid-term elections next year. So maybe “peak” tariff and DOGE worries are behind us.

Third, the backdown suggests the tariffs are more about making a deal (“escalate to de-escalate”) than shifting most production back to the US to usher in an (imagined) “golden age of America”. Imagined because returning all manufacturing to the US would mean a huge increase in prices and most Americans think international trade is good and don’t want to work on production lines anyway. Positive in this regard was Treasury Secretary Bessent’s comment after talks with China that “neither side wants to decouple.”

Fourth, the backdown tells us that Trump is constrained after all. While Trump and his team were claiming not to be worried by the fall in shares (claiming it’s just a “little disturbance” and “corrections are healthy”), when US shares neared a bear market, the US bond market started to become dysfunctional and there was much talk of recession and a public backlash over the tariffs, he started to back down.

In other words, investment markets, the economy and public opinion are still a constraint. A rising share market is still a KPI for him!

Finally, this adds to confidence that Trump will pivot to the more market friendly supply side policies of his agenda around tax cuts and deregulation through the second half of the year. In this regard Congress is getting closer to resolving the tax cut bill.

This all holds out hope that after the 15% plus correction, shares can rise further through the second half and produce positive returns this year, albeit probably less than the strong returns of the last two years.

The bad

The bad news is that we are not out of the woods yet.

First, the “reciprocal tariffs” are just paused for 90 days, so it could all flare up again by July/August if trade talks do not make enough progress. The deal with the UK was easy for the US as it has a goods trade surplus with the UK. But negotiations with some countries that have a trade surplus, like Japan and Europe, don’t appear to be going smoothly. It may also be hard to make progress with China. Some deals will just be agreements to negotiate.

And Trump’s recent comments that some countries with surpluses are “going to pay a 25% tariff or a 30% or a 50%...” suggest there is a high risk of him throwing another tantrum, emboldened by the rebound in shares.

Second, the current level of US tariffs – particularly the 10% rate – looks to be the base assuming deals are cut. That suggests that the tariffs either stay here if deals are cut or move up if not. And Trump’s talk of tariffs to come on pharmaceuticals and movies suggest some renewed rise is likely even if trade deals are struck with all countries.

Third, this in turn suggests that the best Australia might hope for is relief on the 25% tariff on steel and aluminium (and any future tariffs on pharmaceuticals and movies) but the 10% tariff will remain.

Fourth, if the current average US tariff of 14% is as good as it might get, it’s still five times higher than at the start of the year and above where many had expected it to settle – our assumption has been for around 10%. So, it still implies significant economic disruption.

Finally, while confidence readings may see a bit of a bounce on the backdown from Trump, hard economic data for things like retail sales, jobs and business investment are still likely to slow particularly in the US and as businesses go through another few months of uncertainty waiting to see how things settle down after the 90-day pauses.

So, after the strong rebound in shares they could still go through another rough patch in the months ahead before things sustainably improve.

And the ugly?

More fundamentally, there are some aspects of Trump’s approach and policies which may be seen as “ugly” from an investment perspective.

First, the chaotic approach to policy making where policies are announced then reversed is leading to heightened uncertainty. This is amplified by a lack of clarity as to what Trump really believes. Uncertainty is the enemy of decisions to spend, hire and invest. And US economic policy uncertainty has gone through the roof on some measures. Maybe this “strategic uncertainty” is The Art of the Deal. All good, if good deals are reached, but the longer it goes on the more damage it causes.

.png)

Second, the Trump Administration’s unclear view about the $US as a reserve currency which (along with its chaotic policymaking) could lead to renewed fears of capital outflow in turn putting further upwards pressure on US bond yields. Signs of these worries were starting to emerge last month and may start to flare up again as the tax cuts come into view with less revenue from tariffs and DOGE savings being less than expected meaning a worsening budget deficit.

Third, his verbal attacks on US allies are adding to uncertainty as to whether the US is a reliable defence partner. This is in turn adding to geopolitical uncertainty and furthering the reversal of the “peace dividend” that helped the bull market in shares from the 1990s.

Fourth, the Trump administration is weakening US institutions that have been key to US success including: the rule of law and the court system (with the Administration often defying court orders); universities (with cutbacks to research funding at Harvard, etc); and the Fed (with numerous attacks on Fed Chair Powell and a desire to appoint someone who is more pliant with his views). His attacks on DEI, the free press and economic statistics may be added this.

Taken together this can result in more uncertainty, less innovation and higher inflation over time. In particular, the independence of the Fed is key to keeping US inflation low and stable.

Finally, Trump’s protectionist agenda via tariffs will likely further accelerate the reverse in globalisation seen in recent years as evident in a declining share of exports and imports relative to global GDP. Increasing protectionism will mean less competition and less innovation which can mean lower real GDP growth and higher than otherwise inflation.

Taken together these things could mean lower productivity growth, lower real GDP growth and higher than otherwise inflation. This in turn could mean lower medium-term investment returns from shares.

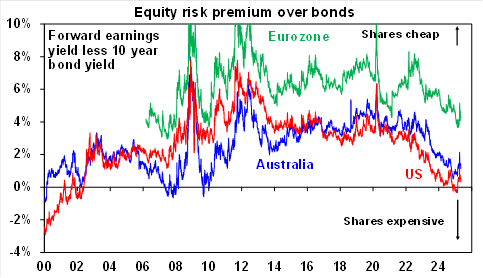

Looked at another way, they beg the question whether the risk premium on shares (as measured by the gap between forward earnings yields and bond yields) – particularly for US shares where it’s around zero - is too low, given the uncertainty and threat to productivity and growth. Particularly with bond yields under upwards pressure from US budget deficits.

Need for balance

However, we need to be careful not to get too negative here as some of Trump’s policies are actually very pro-growth and supply side focussed – namely tax cuts and de-regulation. So, if these start to get the upper hand and technological innovation with AI continues, then this will provide a powerful offset to the negatives cited above.

In other words, it’s premature to start revising down longer-term share market return assumptions based on the first four months of Trump 2.0.

And a final thought: switching to cash or a conservative super option at the height of the share market plunge in April would not have been a good move. The experience of the last month highlights the difficulty in timing markets and why it’s better to stick to a long-term strategy.

4 topics