The big RBA forecast miss on Q3 inflation

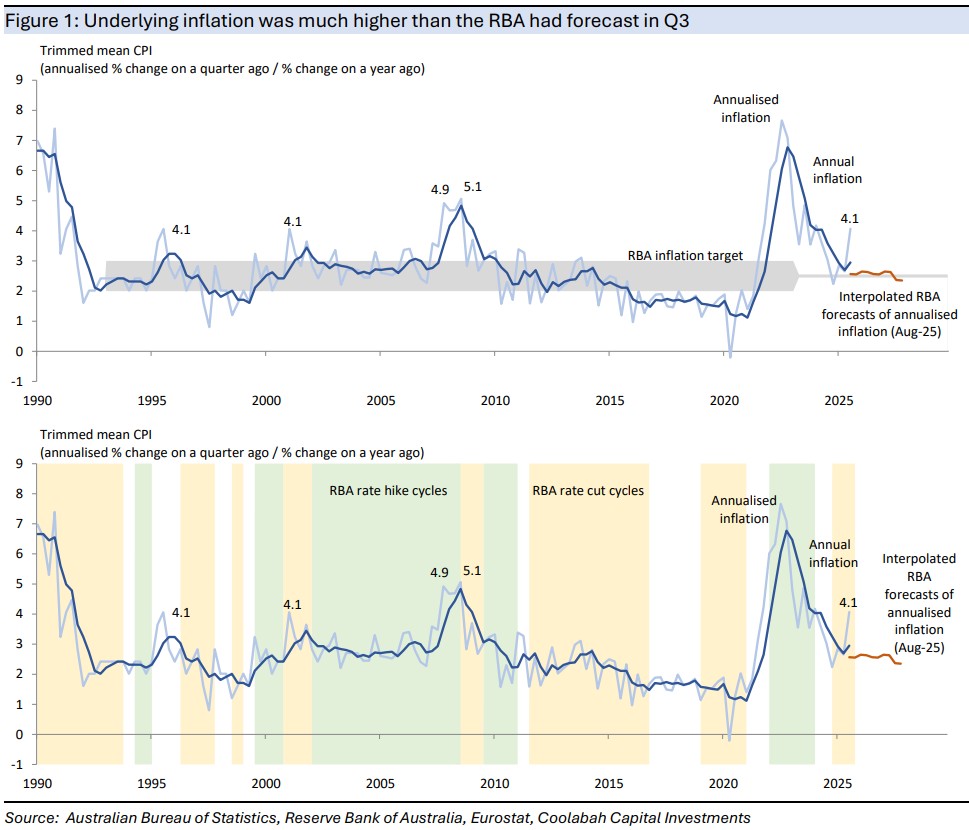

After a few encouraging readings on quarterly inflation that allowed the RBA to cut rates, consumer prices spiked in Q3, rising by an annualised rate of 4% in underlying terms, as foreshadowed by the monthly CPI. Outside of COVID, this was one of the highest readings on inflation since the RBA began targeting inflation in 1993.

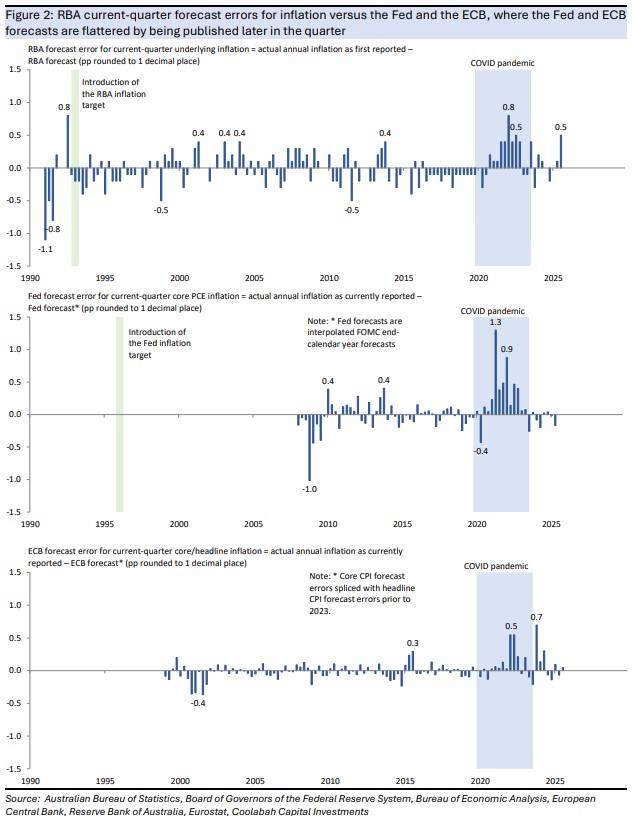

With quarterly inflation revised up from 0.6% to 0.7% in Q2, this meant that the RBA staff’s forecast miss for annual underlying inflation in Q3 was 0.5pp. Excluding a couple of extremes in inflation during COVID, this was the largest upside surprise for a current-quarter forecast since late 1992. It was also one of the RBA’s largest forecast misses in absolute terms on record.

It is also a relatively large forecast error compared with the track records of the Fed and the ECB, where inflation is similarly volatile across the three economies. The Fed and the ECB’s forecast errors are a little smaller than the RBA’s errors, although to be fair the comparison is not like-for-like and flatters the forecasting ability of the Fed and the ECB. The RBA publishes its estimates early in the middle month of the quarter, while the FOMC and ECB estimates are published in the final month of the quarter, such that the Fed and ECB have access to more actual monthly inflation and labour market data when preparing their forecasts.*

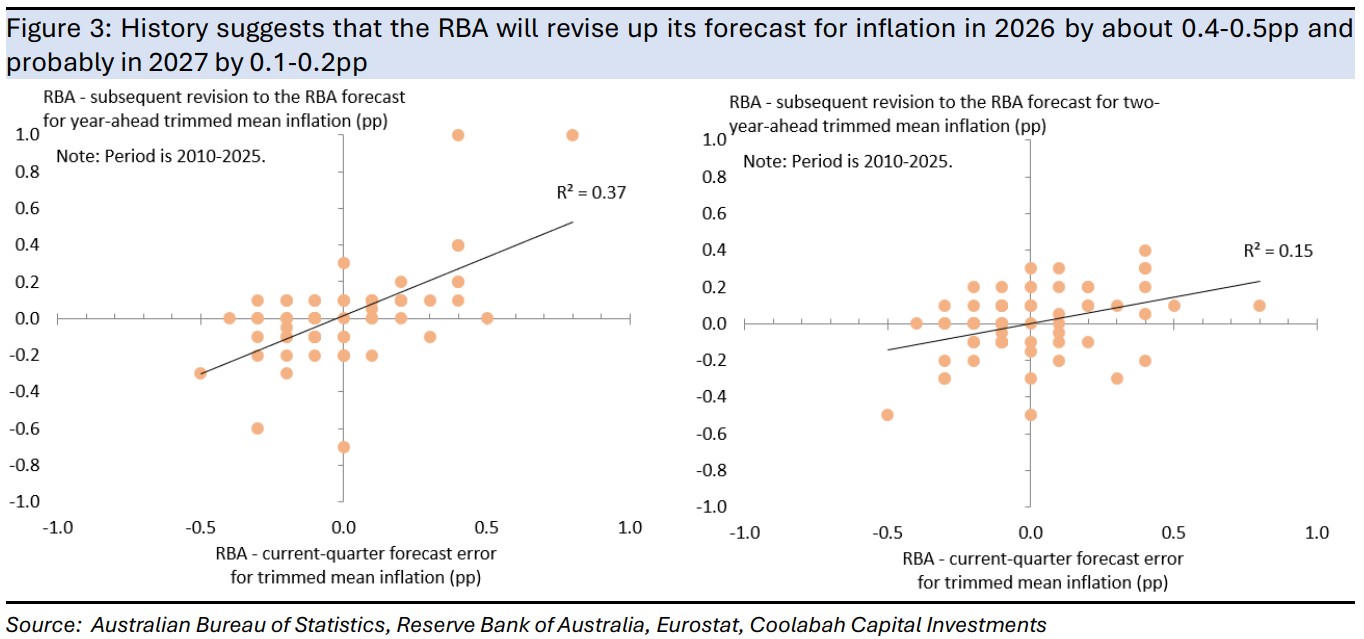

The RBA staff will publish the updated economic forecasts that the board has considered at its policy meeting in tomorrow’s Statement on Monetary Policy. Given the much higher starting point for inflation in Q3, our analysis suggests that the end-2026 forecast could be revised up from 2.6% to around 3%, with the risk that the end-2027 forecast is revised up from 2.5% to either 2.6% or 2.7%.

The longer-term forecasts for inflation should be helped by a higher forecast profile for the cash rate, assuming that the RBA still thinks the neutral cash rate is about 3¼%. The forecast cash rate is based on market pricing from the week before the forecasts are finalised, which in this case is about 20–40bp higher over the next couple of years than assumed for the August Statement on Monetary Policy.

If much higher inflation in Q3 is only partly unwound in Q4, this would completely derail the RBA staff’s outlook for inflation and force the RBA board to rethink whether it was overly optimistic in believing that the NAIRU had fallen to 4¼% – versus the staff model estimate of 4¾% – and that monetary policy was still tight given the neutral cash rate was judged to be 3¼%.

Note:

* That said, the Fed estimates are at a

disadvantage in that they are simple interpolations of median FOMC end-year forecasts.

The ECB forecasts are at a disadvantage because the short history of forecasts for

underlying inflation was spliced with forecasts for more volatile headline inflation.

Also note that the RBA forecast errors were calculated using inflation as first

published, while the Fed and ECB errors rely on the latest available estimates

of inflation.

5 topics