The Fed might be done, what's next for equities?

Bond yields are down, and equities have put in a big rally starting from a deeply oversold position.

The past 12 months have shown the negative correlation between government bond yields and equities momentum can be a very powerful driver.

Assuming the US Federal Reserve is now done with monetary tightening, what should equity investors expect from the year ahead?

In a strange twist of "the market is always a compilation of competing views and narratives," both bulls and bears are claiming history shows the scenario for 2024 will be written in line with their views for, respectively, strong gains or more weakness ahead.

Surely, history cannot be that ambiguous? Or is this simply a case of we, humans, simply see what we want to see?

Time for an investigation

Probably the precedent most referred to in 2023 is that of late 2018/early 2019 when the US share market effectively forced the Federal Reserve to stop hiking interest rates by falling -20% between September and Christmas.

Once then Fed chair Jerome Powell and the board gave in to the market's demand, stability returned and the US share market resumed its pre-September uptrend to advance no less than 27% by late 2019.

In Australia, the ASX 200 followed suit with a total return, including dividends, of 18.4%.

So far, so good. Central bank policy pauses seem extremely beneficial for equity markets.

However, to tell the full story of 2019, we need to include the fact Powell and co started cutting the key benchmark rate from the 31 July meeting onwards. There would be two more rate cuts and by September central bank officials were bailing out hedge funds and non-bank financials as the US repo market stopped functioning, threatening another financial crisis.

The RBA started loosening in June and would cut five more times by the time COVID-19 spread across the globe. It is easily forgotten, but by the second half of that year, before anyone knew a global pandemic was coming, Australia's energy companies and other cyclicals, plus three of the Major Banks in Australia, started announcing dividend cuts to shareholders.

Not helped by a Royal Commission digging deeper into the sector, and uncovering all kinds of mischief and malpractices, banking analysts were preparing for what looked like a truly horrible year ahead (more dividend cuts coming!).

Soon after, of course, the world was gripped by a major pandemic. Today, we don't know what the outcome would have been without it. What we can conclude with sufficient certainty is the post-2018 Fed pivot story never ran its full course. It was cut short and interrupted by covid and societal lockdowns, and by extraordinary government stimulus programs, the world around.

But the share market bulls have a valid point: in the six months post the Fed's policy change, US equities rallied by 17.8%. In Australia, the ASX200 gained 12.4% between January and June 30 on strong gains for mining and energy stocks, while the financial sector lagged but still gained 11.1%.

Recessions and crises

2018/19 is not the only time a pause in Fed hiking has led to strong gains for share markets.

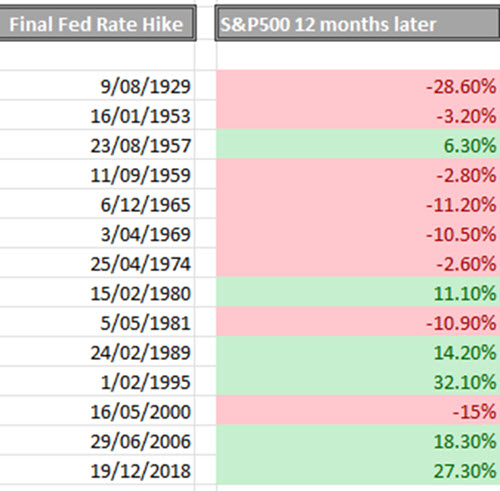

Other examples from the past 90-plus years are mid-2006, 1995, 1989, and 1980. In 1957 the first six months were negative, but twelve months out the share market was back in the black.

To be fair, the number of times when the Fed stopped hiking and equities were subsequently in for a negative performance has happened more often; eight in total versus six.

Maybe the bears have a valid point here: it looks like the bulls are cherry-picking from positive experiences.

It is interesting to note nevertheless, pre-1974, only one of the post-final Fed hike years managed to end on a positive note, and then only after six months. Since the early 1980s, there have been seven occasions, 2023 not included, and five of those seven occasions have seen equities rally strongly in the first six and 12 months.

It looks like the bulls might have a point: maybe economies have changed so much that impacts from higher interest rates do not necessarily equal economic recession in the aftermath. This would undoubtedly be great news for equities.

One of the historical flashbacks that is circling around on social media:

Once we start looking into the finer details behind the first 12 months' performances from the day the Federal Reserve stopped hiking interest rates, it soon becomes clear the outlook for equities very much depends on whether economic recession follows next, and when exactly.

One alternative scenario is that of a financial crisis. Few who were in the market back then will ever forget the global crisis that unfolded in 2008. Back in 1965, Fed tightening did not cause economic recession, but a good old credit crunch caused a financial crisis in the following year, which might explain the negative return in the table above.

It is also commonly believed Fed tightening up until early 1995 is linked to the subsequent Asia crisis that started in Thailand in July 1997.

This year has seen regional banks in the US and Credit Suisse in Europe narrowly avoiding the abyss. Back in 2019, as stipulated earlier, the Federal Reserve managed to nip a new financial crisis quickly in the bud. Arguably, the crypto space did come unstuck on lower liquidity and tighter central bank policies, but it wasn't important enough to be saved.

Can we safely assume any new forms of important market stresses will be just as quickly and effectively dealt with as on each prior occasion post-GFC?

Let's hope this will be the case.

The Fed, however, does not have the tools to prevent the US economy from weakening into negative growth, certainly not when it is targeting lower inflation. This makes economic recession possibly a much bigger threat for equity markets in the year ahead.

What all the negative references in the table above have in common is simply that – economic recession.

1965 is the exception; it was followed by a financial crisis instead. And while 1957 shows up as a positive on the table, it marks one of those occasions when recession arrived early during Fed tightening. The first six months after the final hike pulled the S&P500 down by -8.2%.

This takes us back to 2019 and the other positive precedents. While the story remained unfinished by the time COVID arrived, bond markets in 2018 had never inverted during Fed tightening. So, one can conclude the share market was simply having a conniption that year, without any hints of economic recession being a genuine possibility.

Certainly, the bond markets weren't forecasting any economic contractions in the foreseeable outlook. We know this time is different. This time bond markets have been predicting a major economic slowdown is ahead (they still are).

Viewed from this crucial angle, a different perspective emerges from the table above. The US economy did fall into recession in early 2008. The aftermath of the tightening cycle that ended in mid-2006 thus effectively led to a double whammy negative outcome of economic contraction, globally, plus a Global Financial Crisis.

No wonder equity markets lost half their value between late 2007 and March 2009. But equally important: should we then focus on the positive 18% return that preceded the subsequent carnage?

Are post-Fed pause positive returns simply a matter of "timing"?

There are hints of that, most certainly. The negative performance of 1981 fully erased the positive return of 1980. The US economy experienced an economic recession in 1990, which was preceded by the Fed pivot and a positive return the year prior. That period marked, equally, the build-up to what came to be known as the Savings & Loans (S&L) financial crisis that didn't end until the mid-1990s.

The 1995 pivot never led to recession, but a financial crisis followed 2.5 years later. That time the US bond market did invert, which can be, in hindsight, interpreted as a false signal.

According to some analyses, economic recession did arrive, but not until 2001 - six years down the track, with an Asian crisis, the Nasdaq meltdown and 9/11 happening in between.

Conclusions

Summarising all of the precedents, I think it is only fair to conclude that:

- Fed tightening cycles are likely to lead to economic recession and/or financial crises, though not necessarily during the tightening process or immediately after it.

- It is possible both economic recession and financial crisis can be avoided, though history suggests this only happens on a small number of occasions. Arguably, this only happened in 2018, and maybe only because of the arrival of a global pandemic by late 2019/early 2020.

- All other occasions have been followed by economic contraction or a financial crisis, or both. On a number of occasions, the negative impact of tightening showed up rather slowly. This allowed share markets to make the best of it in the meantime, no doubt also led by the belief that "this time is different" and a "soft" or "no landing" was on the cards.

Final conclusion: it appears history shows both bulls and bears can have their cake and eat it too. They both can look at historical precedents and see their views confirmed. The difference can be simply due to a difference in timing.

This does not provide investors with a watertight blueprint for the year ahead. The US bond market has been suggesting since March 2022 a substantial deceleration in economic momentum lies ahead. Economic indicators are suggesting momentum is slowing, without flagging a fall-into-the-abyss experience soon, but market participants will be paying close attention.

If we simply focus on the past three decades, it is well possible negative outcomes from central bank tightening take more time to work through modern-day economies, hence providing equity markets with an opportunity to rally first and suffer the consequences later.

Whether this proves to be the case in the year ahead, then comes down to 'timing' - assuming history rhymes in 2024.

Equally important: economies can avoid recessions, but this doesn't negate scenarios whereby growth can slow dramatically.

History also suggests bond yields should come down as economic growth slows (as does inflation), which supports equity valuations, but not when growth and corporate earnings turn negative.

FNArena offers truly impartial share market commentary and analysis, on top of proprietary tools and data for self-researching and self-managing investors. The service can be trialled here (VIEW LINK)

5 topics