The need to raise living standards through productivity

Labour productivity – which is the output each person produces in the economy – matters hugely for every Australian.

As Nobel Prize-winner Paul Krugman famously said, “Productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country's ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

The government can mask poor productivity by boosting economic growth by adding to the population, but if an individual wants to earn more, they are best to be more productive.

Put simply, productivity and living standards go hand in hand; when productivity booms, living standards boom, and when productivity disappoints, living standards disappoint.

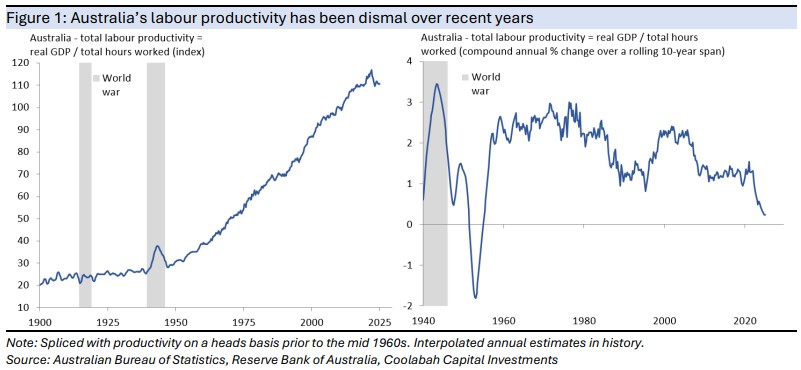

Unfortunately, Australia’s productivity performance has been dismal, with both the worst performance in decades and poor performance compared with other struggling western nations.

What is meant by dismal productivity? Well, on average, each Australian is producing much the same as they did almost a decade ago, back in 2016.

The last time Australia’s productivity was this weak over such a long span was when World War 2 ended and the workforce absorbed the troops returning home. Otherwise, the comparison stretches back to a century ago to the 1920s.

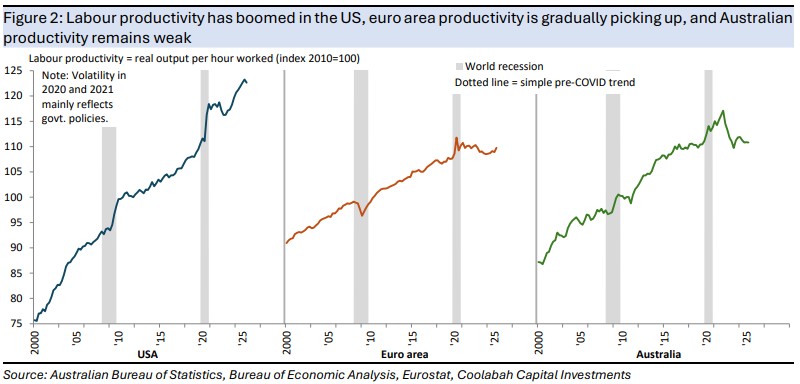

Australia is not alone in facing this challenge as almost every country has been in the same boat over recent years, with the US the outlier as labour productivity there has continued to boom.

However, Australia is struggling more than most of its peers. To place Australia in perspective, continental Europe is widely thought of as a low-growth, low-dynamism economy, held back by too many regulations.

It is true that European productivity has been weak, but it has actually done a bit better than Australia, with the level of productivity slowly picking up to reach its best level since COVID hit in early 2020.

Why has Australia disappointed? It is a mix of factors: an ageing population demanding more government services, companies not investing enough in their workers, and companies not investing enough in technology.

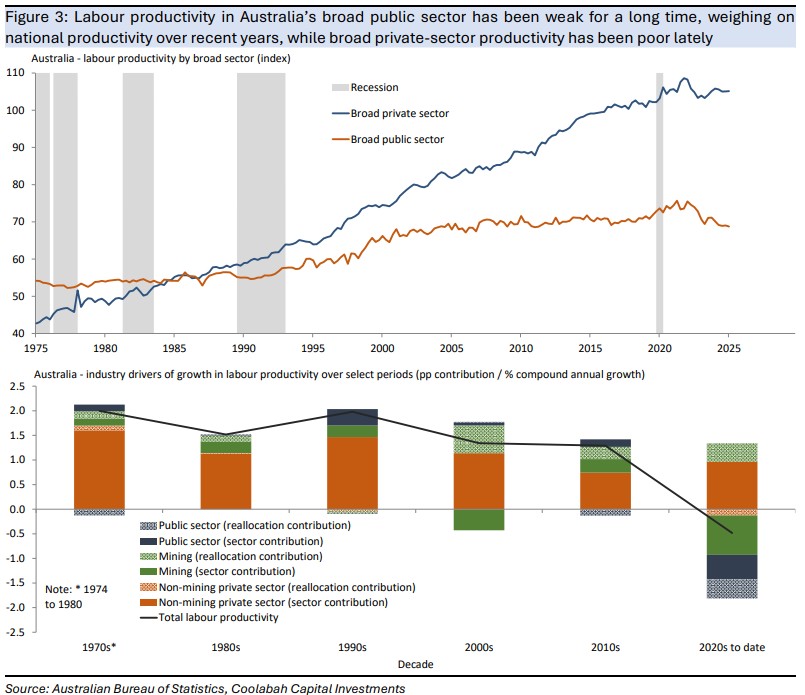

How pervasive is the influence of government on productivity? Well, first up, the public sector has grown in importance.

Over the past 10 years, an extra 2.9 million people found work, where just over half – or 1.5 million of them – were hired in the broad public sector.

All this growth in the public sector means that almost 1 in 3 people now work in either the public administration, health and social welfare, or education industries.

Moreover, if you look across Australia, the health and social welfare industry is in the top three employers in most suburbs and towns and it is often the largest employer.

These trends are in no way unique to Australia, holding true for the ageing populations of other advanced economies, where Australia’s broad public sector share of employment only places it in the middle of the global pack.

Not surprisingly, the same outsized strength in the public sector shows up in economic activity. For example, over the past ten years, Australia’s economy has grown by about 2¼% per annum, with government spending accounting for 1¼pp of that growth.

As a result, government spending has averaged almost 30% of GDP for nearly all of the past year. This matches the brief stimulus-driven peak at the height of COVID and is only exceeded by the spending undertaken during the Second World War.

But to bring it back to productivity, the public sector’s productivity has stagnated for just over twenty years, with the level of labour productivity about the same as it was in 2004.

Why is this the case? Government spending on infrastructure provides a great benefit to productivity, but its benefit is mainly felt by the private sector, while boosting the productivity of labour-intensive jobs in, say, health, aged and disability care is difficult.

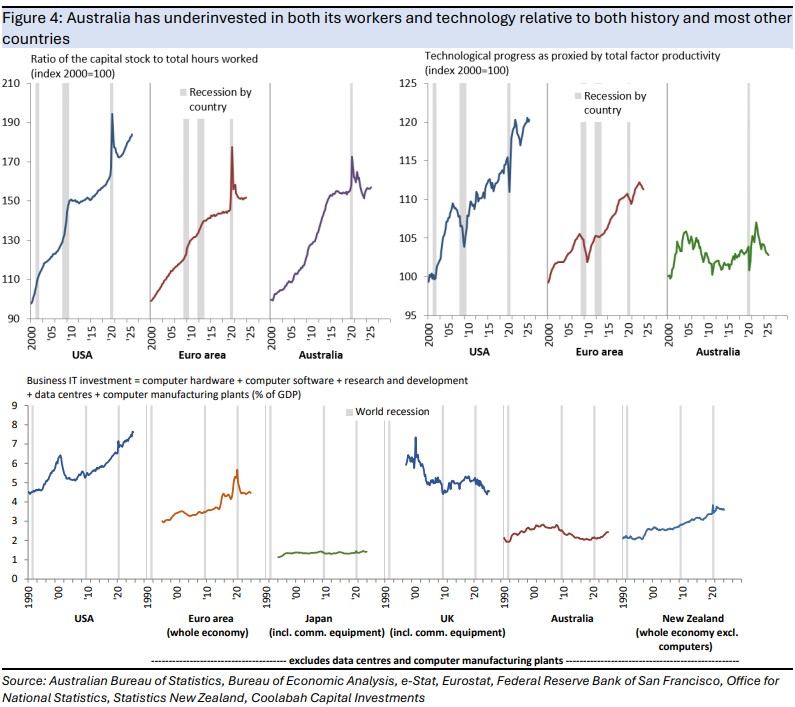

What about sluggish productivity in the private sector? Two obvious culprits are investment and technology, where a worker can be made more productive by investing more in them and using technology to be more efficient.

Unfortunately, Australia is lagging on both counts.

If you look at Australia’s capital stock per worker, it is about the same as what it was almost a decade ago, showing that many companies find it easier to hire more people rather than invest in their existing staff.

In this respect, Australia has been left behind by American companies, where business investment is booming, and even Europe.

Australia is even more behind on technology. If technology is measured using what economists call multifactor productivity, it is broadly the same as what it was almost a quarter of a century ago, back in 2001.

This sort of sustained weakness hasn’t been seen since the early 1960s and, again, Australia has been left in the dust by the US and, to a lesser extent, Europe.

The natural question to ask, though, is whether AI changing things and if Australian firms are investing in artificial intelligence and big data to keep up with the global competition.

Looking at business investment in technology, Australian firms have started to lift their spending, but it is still low at about 2½% of GDP. European competitors are spending about 4½% of GDP on tech, while US firms are spending 8% of output.

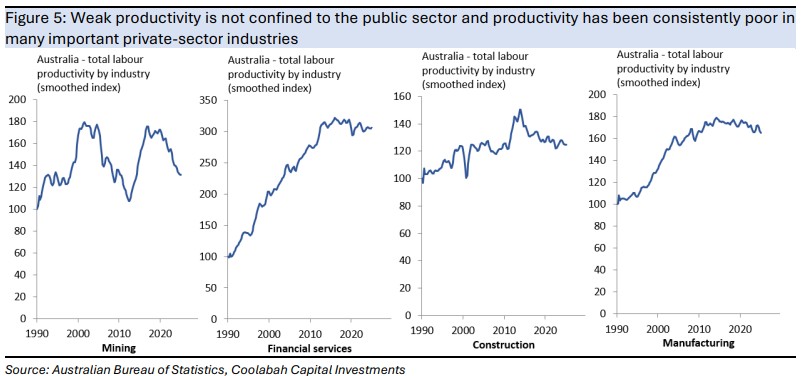

Keep in mind, though, that weak productivity is not confined to the public sector and productivity has been poor in several important private-sector industries.

Productivity has stagnated for years in industries like mining, which has been a notable drag on national productivity, the financial sector, which is dominated by the banks, construction, and manufacturing. In contrast, productivity has done OK in sectors providing services to businesses, farming, and wholesale/retail.

All this leads to the question of what happens if Australia doesn’t invest more and spend more on technology to fix productivity.

The most obvious thing is that living standards will be stuck in a rut. Australian companies will be less competitive than their US, European, and Asian peers and Australia’s economic growth will be weak unless the government props it up by boosting the population.

The economy would also risk becoming more lopsided, relying on competitive advantages in mining, education, and tourism, with the government continuing to play a large role as Australians become older.

5 topics