VGI's hedge fund top of the pops

In my column today I argue that to have any hope of divining the prospects for 2019, one has to first solve the Rubik’s Cube that was 2018 in which the most overvalued asset-class on the planet, government bonds, reigned as king—trumping cash—despite this column’s contrarian forecast of four Fed rate hikes coming to fruition (click on that link to read the column or AFR subs can click here). Excerpt enclosed:

In 2018 everyone was trying to slash so-called "duration" risks—or their portfolio sensitivities to increasing interest rates—precisely because they were (justifiably) concerned that rates would climb. And they did: the Fed lifted its cash rate four times while the 10 year US treasury yield, regarded as the global risk-free rate, surged from 2.41 per cent at the end of 2017 to as high as 3.24 per cent in 2018, finishing the year at 2.72 per cent.

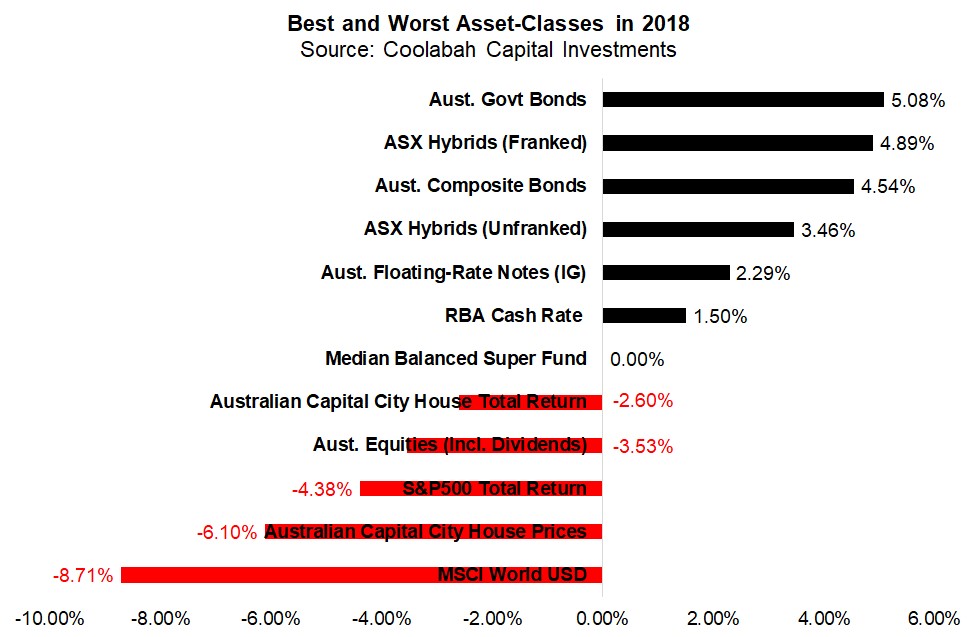

As a consequence, 10 year US government bonds performed poorly, furnishing a miserly 0.88 per cent return. Yet after posting similarly miserable returns with three chunky individual monthly losses around 0.5 per cent, the fixed-rate Aussie government bond index pulled off the mother of all miracles with a 5.08 per cent return in 2018, beating all other mainstream investment options. (Note that return is more than double its yield and an artefact of a sudden decline in interest rate expectations.)

Ten year Aussie government bonds might only yield 2.23 per cent today (and come with return volatility that is higher than an ASX hybrids portfolio), but this yield was 2.94 per cent in early 2018. (The average 10 year government bond yield since the RBA started targeting inflation in 1993 has been 5.35 per cent.)

The late 2018 equities capitulation—on, ironically, concerns about the impact of higher rates on share prices—convinced investors to engage in the mother-of-all bond buying binges in December, which coupled with the dovish impulse of falling house prices helped the Aussie government bond index jump a massive 1.92 per cent in December.

No less surprisingly given a savage 100 basis point blow-out in their credit spreads after the ALP’s announcement on franking credits, listed hybrids were the second-best performing asset-class in 2018 with an impressive 4.89 per cent return. This was followed by other corporate bond benchmarks. So cash was not king—bonds and hybrids were.

Loaded up to the gills with listed and unlisted equities, the median "balanced" super fund had a dog of a year, returning nothing at all. House prices fared worse, down 6.1 per cent in price terms, or 2.6 per cent lower after accounting for rents (but before costs). Worst of all was global equities, off a hefty 8.71 per cent in US dollar terms…

Looking ahead over 2019, I believe that the passage of time will prove that equity and bonds are trading off circular and arguably inconsistent logic. The causality has run from stronger growth/inflation in the US (as we predicted) driving higher long-term interest rates, which have pushed equity values lower (as they should).

Yet this has then paradoxically compelled bonds to rally, shunting long-term interest rates lower with—in our view—no real fundamental changes in the original growth/inflation outlook notwithstanding the normal business cycle volatility and a temporary blip induced into global manufacturing activity from Trump’s trade war.

It is clear that the equities market story in 2018 was a "discount rate drama". The big 8 per cent to 10 per cent intra-month losses suffered by global shares in February, October, and December were demonstrably based on fears of rising interest rates, which were being driven by US economic strength.

In February and October it was surging wages and 10 year government bond yields, while in December it was concerns around the Federal Reserve not being dovish enough and dropping its previously proposed 3 hikes this year (they had the audacity to keep 2 hikes in their projections).

The discount rate drama was amplified by, variously, the US-China trade war, which should be resolved this quarter, Brexit, which will be sorted out one way or another, North Korea, which is now on the sidelines, Italy and Turkey, which have faded as concerns, and manifold other Trump-related uncertainties. While Trump was manna from heaven for markets in the first year of his tenure, he turned into Dr Strangeglove in 2018, perhaps propelled by the hubris of the market's ebullience during his opening stanza.

After the bond market tried to ignore the early bouts of equity weakness, it has, for the time being, reverted to its historically anomalous, post-global financial crisis reflex of an inverse (or negative) correlation with shares, which gripped strikingly in December, driving the crazy bond returns in that month. Equities and bonds have been positively correlated most of the last 150 years, including during the 1980s and 1990s, and tend to have a positive (negative) correlation in inflationary (deflationary) shocks.

There is, however, an inherent contradiction in the market's logic: equities have been petrified about US 10 year government bond yields rising above 3 per cent. So when they start getting hammered every time the discount rate duly breaches this level, bond prices have rallied hard, slashing the discount rate back down again to historically very low levels.

It is a psychological game of pass-the-parcel: either we (and the early equities' reaction function) are going to be right and the global inflation cycle is building, which will force long rates higher, or government bond junkies know more than we do and a global recession is looming.

I would submit that the empirical case for our inflationary thesis has never been more persuasive, albeit that it will inevitably take time to fully play out. Yes, global manufacturing indices have rolled over, but this seems to be largely a function of pull-forward demand driven by the trade war and the desire to stockpile cheap inventories before tariffs bite, with the flip-side being temporarily weak data until the dispute is settled.

The prospect of a deceleration in economic growth in 2019 and an increasingly dovish Fed is only likely to elongate the post-GFC expansion in the US. Some folks worry about US GDP growth falling back to its trend rate around 2 per cent, but this is exactly what should happen when the Fed lifts its cash rate 8 times to a level that is within its “neutral” range.

Our bottom line is that the 2018 volatility was not being driven by fundamentals per se, but rather by uncertainty and noise. And that is likely a buying opportunity for financial credit, which is one of the few cheap asset-classes vis-a-vis pre-GFC marks, especially accounting for the striking deleveraging of bank balance-sheets and the new-normal of streamlined, utility-like businesses characterised by extreme risk-aversion that is negative for equities and positive for creditors.

The price action in January has certainly vindicated this view, and should lay the foundation for a period of normalisation in spreads and superior returns. We have observed a very strong bid for bank senior bonds, sharp spread compression in subordinated debt, and outstanding capital gains across the hybrid market, echoing global moves as investors desperately scramble to buy the credit they dumped in late 2018.

4 topics