Why holding excess cash is risky

When interest rates on deposits are so low and are likely to stay this way for many years, it is worth checking if you are holding more cash than you require. One clear outcome of very low interest rates is the tendency for some savers to hold even more cash as they become more uncertain and risk-averse.

This is called a liquidity trap and it is one reason the RBA is avoiding the use of negative interest rates. Any investor who finds themselves in such a situation should deeply question their decisions as better alternatives may be available.

Money illusion

For those who realise they do not require much immediate liquidity, an additional return for their patience can be obtained. However, even for investors who find it hard to deploy their cash holdings into exposures with the volatility of equities or other growth assets, far better alternatives to deposits or term deposits may be available.

Gaining exposure to well-compensated credit risks and being prepared to step slightly outside of the mainstream can provide meaningful upside relative to cash. Even so, some investors will be concerned about the theoretical potential for losses.

It is important to realise that a loss occurs when the same $1 buys less than it did last year. When inflation makes goods and services more expensive relative to (after-tax) interest rates, the purchasing power of cash has declined and a real loss has been incurred.

Investors insisting this is not the case are suffering from a term called ‘money illusion’, where they believe that no losses have occurred when a dollar figure in their bank account has not changed. Losses have occurred.

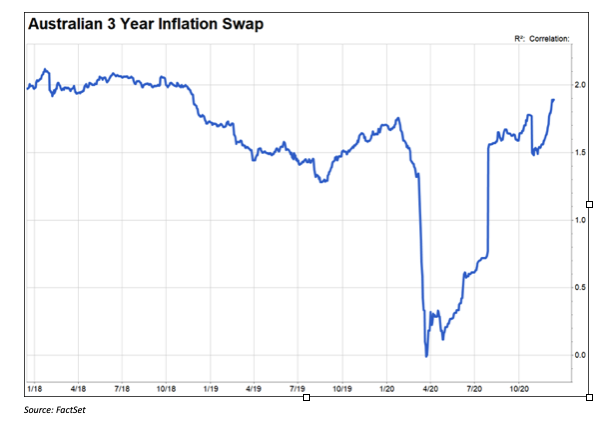

As economic expectations are now improving, the expected rate of inflation over the next three years is close to 2% per annum. The difference between this figure and cash could be expressed as a negative real interest rate of 2% per annum to hit the point home. Holding cash is very risky for investors without immediate cash needs.

Why investors fall into liquidity traps...

Interest rates tend to decline when the economy requires more stimulus. By dropping official rates, the RBA and other central banks reduce the cost of borrowing in order to stimulate lending which, in turn, can stimulate the economy. The economic impact of COVID-19 has meant that the economy requires extreme measures to rebalance.

The measures required are so significant that low cash rates alone are not sufficient and the RBA has also undertaken additional measures to ensure that the market expects that rates will stay close to zero for at least 3 years. These actions include:

- Buying government bonds, without limit, to ensure that the 3-year yield is approximately 0.1% per annum;

- Announcing that they do not expect to raise rates for at least 3 years; and

- Explaining that they will not raise rates until realised inflation has sustainably reached the target band of 2-3% per annum.

By anchoring expectations beyond the immediate future, the RBA believes that borrowers can be even more confident that interest rates will remain low. This would, for example, provide more assurance for a new home buyer.

... And why they find it so hard to get out

Investors respond to these developments in different ways, but some become even more risk-averse. The economic outlook can be extremely poor at such times. Many investors will have experienced losses and the fear of incurring additional losses in the near term can be overwhelming. However absorbing losses are part of the journey for successful long-term investors. The behavioural costs attached to over-reacting to nearer-term investment outcomes can be very significant.

Whilst some investors are genuinely better served by moving to cash in these situations, many are not. Behavioural investors understand that it can be awfully hard to restore a long-term investment mentality when under duress. Nonetheless, some helpful questions to ask are:

1. Do I really need that much money at call (or near call)?

Most of us usually spend a small fraction of our wealth in any short term period. Further, we have other assets we can sell to meet liquidity needs. There is nothing wrong with selling other liquid investments if you need access to funds. It is important to consider the total available liquidity in a portfolio. In a superannuation environment, during the accumulation phase, the liquidity in the portfolios is not even accessible, for example.

2. What is the best way to maximise my chances of a good outcome?

What mix of assets maximises the chance of achieving savings goals? Unless savings targets are approaching a high level of impairment where further risks just cannot be borne, most investors are better off taking a longer-term investment perspective. By focusing on long-term objectives, it may be possible to shake-off near-term fears.

If an investor chooses to re-assess their circumstances and re-deploy excess cash holdings, moving towards a greater growth orientation can still be a big step. For some, the risk of capital loss, as might be associated with a portfolio of shares, can still be hard to accept. Smaller steps may be required.

The price of liquidity

One such small step would be to move from holding deposits at call (earning essentially no interest) to voluntarily denying ourselves access to funds for an agreed period via term deposits. If we are willing to forgo access to liquidity, this is valuable for a borrower and they are generally prepared to pay for that.

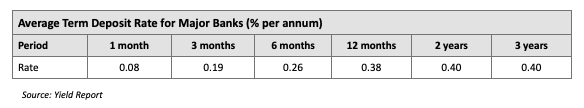

The simplest example is bank term deposits. The following table shows the average rate available from the major banks:

Given the outlook for cash rates is presently flat for the coming three years, the interest rates paid for term deposits can be thought of as the price received for selling liquidity that is not required. As liquidity from listed investments like shares or open-ended funds is available in short periods of time, most investors need relatively little liquidity in the form of cash or at-call deposits and can earn additional returns by selling their right to access funds at short notice.

The price of complexity

The term ‘complexity premium’ refers to an additional return which is available for buying assets that may not be as familiar as others, or have features which are outside of the mainstream.

An example is Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities, which are simply a block of mortgages sold to the market. In financial terms, holding a deposit in Westpac, which lends for mortgages, is quite similar to owning mortgages which Westpac has sold to the market in an RMBS transaction as long as the exposure is supported with adequate capital.

For example, an AAA-rated tranche of a RMBS which was issued by Westpac currently offers a return of close to 80 basis points per annum for an expected three-year term. This compares to Westpac’s three-year term deposit rate of 35bps per annum.

Much of the difference between these returns is the result of a complexity premium. It is not the result of differences in credit risk. Exposure to the AAA-rated tranche of a Westpac issued RMBS is also much more liquid than a term deposit held by an individual investor.

The price of credit risk

As the banking system is crucial for the smooth functioning of an economy, banks are run in a manner to ensure they can withstand enormous problems. Although Australian banks were not impaired by the GFC, the lessons of the event were incorporated into national governance frameworks to ensure that financial stability was not likely to be challenged. Given the vital nature of our largest banks, an even higher level of assurance was required from them.

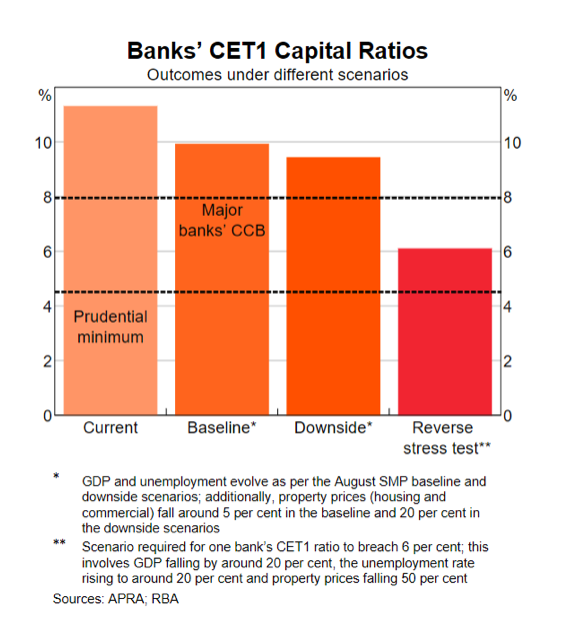

The RBA recently demonstrated that our major banks could withstand a 50% fall in property prices and 20% unemployment without breaching prudential requirements (refer to the Reverse Stress Test in the chart below). This is an event which is similar to the Great Depression in magnitude and much worse than experienced from COVID-19 in 2020.

In addition, they could withstand at least a GFC event on top of that without impairing senior debt or even subordinated debt (Tier2). Under those conditions, several smaller banks would be credit-impaired and large troves of corporations will have ceased to operate. This is an indication of the size of the safety nets which have been built, and they continue to be extended.

Nonetheless, the subordinated debt issued by Westpac to foreign investors, albeit available to Australian institutional investors, which is expected to be called in two years, offers an interest rate of over 300bps per annum compared to Westpac’s two-year term deposit rate of 35bps per annum. Only a small fraction of the difference can be attributed to credit risk and the scenarios under which the credit would be impaired accord with scenarios like war or nationalisation of assets.

Conclusion

Investors who find themselves in a liquidity trap have opportunities to work their way out of it. For many investors with excess cash exposures who still demand low risk of default, it is less risky to real wealth to hold other highly creditworthy and relatively short-dated instruments instead.

Whilst these alternatives could not be said to be cash, they can provide better protection against loss of spending power than cash at call and may offer greater liquidity than term deposits.

Enjoyed this wire?

Click the 'like' button below to let Ken know. For more of Ken's insights, make sure to follow him here.

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned