Why investors do worse than the funds they invest in

Investors tend to do the opposite of what works in investing. We have all always intuitively known that investors tend to buy at the tops and sell at the bottoms. And now, after more than 20 years of reporting on investor behaviour, that observation can be confirmed as fact.

Today, in Australia, investors are mortgaging themselves to the hilt to chase ever-increasing prices for real estate. This, even though record credit card and mortgage debt suggest they can least afford it, and private debt is at record highs. But relief is in sight because it is not the case that record prices and record supply can coexist.

In the stock market, investors have herded themselves into a corner chasing yield and making the most expensive companies those that distribute the most in dividends… but retain the least for growth. Historically low interest rates have also ensured that the Weighted Cost of Capital (WACC) calculation has rendered companies with the most debt, the most expensive.

Historically low interest rates have corrupted investors understanding of risk ensuring they accept bond-like returns or even lower-than-bond-like returns, but take on equity or property market risk. Once again this concoction has never ended well.

Meanwhile, thanks to the faddish behaviour of large institutional investors who found themselves underweight banks and resources right at the moment Trump was elected and iron ore prices started to surge, midcap high-quality and high-growth companies have been sold off – many, as much as 50 percent. The selloff was instigated by large institutional managers that required cash to fund a move back towards market weights in the banks and resource companies.

If there is one criticism, commonly levelled at the quality and value philosophy we are proponents of, it is that quality is easy to identify and rarely cheap. Well, here we are with companies like Healthscope and REA Group down as much as 30 percent in just a few weeks.

What this Whitepaper highlights is that investors rarely see an opportunity for what it really is.

In preparation for 2017 and beyond – which will be interesting (expect bond rates to continue climbing) – this Montgomery Whitepaper seeks to arm you with knowledge of yourself and the real impact of your decision making, ruled as it is by emotion.

Over the very long term, it has been shown that equities provide the highest return for investors, and yet most investors are not reaping the full benefit of these returns. “Perhaps the most compelling evidence that investor behaviour leads to poor decision-making is the end result,” DALBAR said.

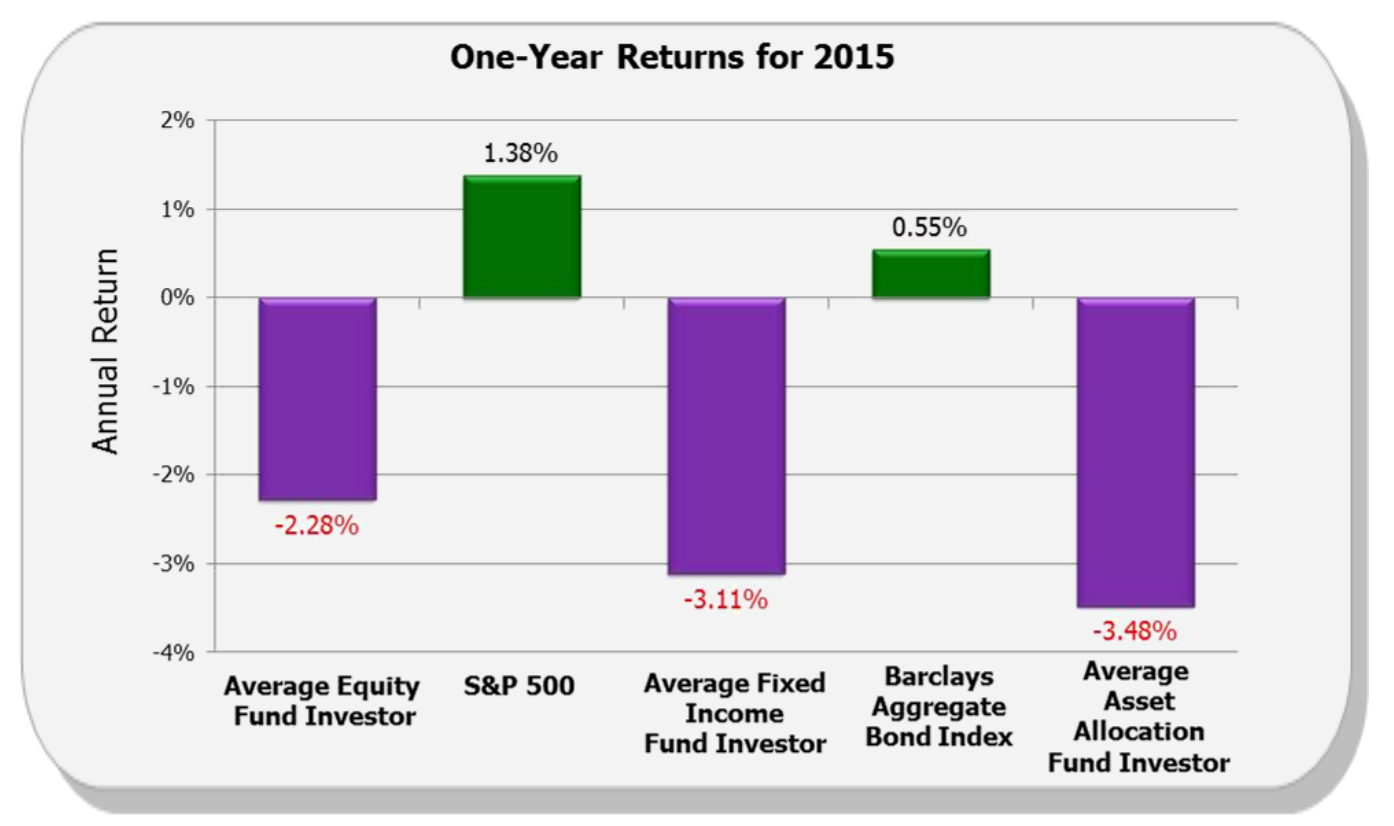

In 2015, the average equity mutual fund investor underperformed the S&P 500 by a margin of 3.66 per cent. The difference between the average fund investor and the overall market was the difference between making money and losing money. As the chart below illustrates, while the broader market made incremental gains of 1.38 percent, the average equity investor suffered a more-than-incremental loss of -2.28 per cent.

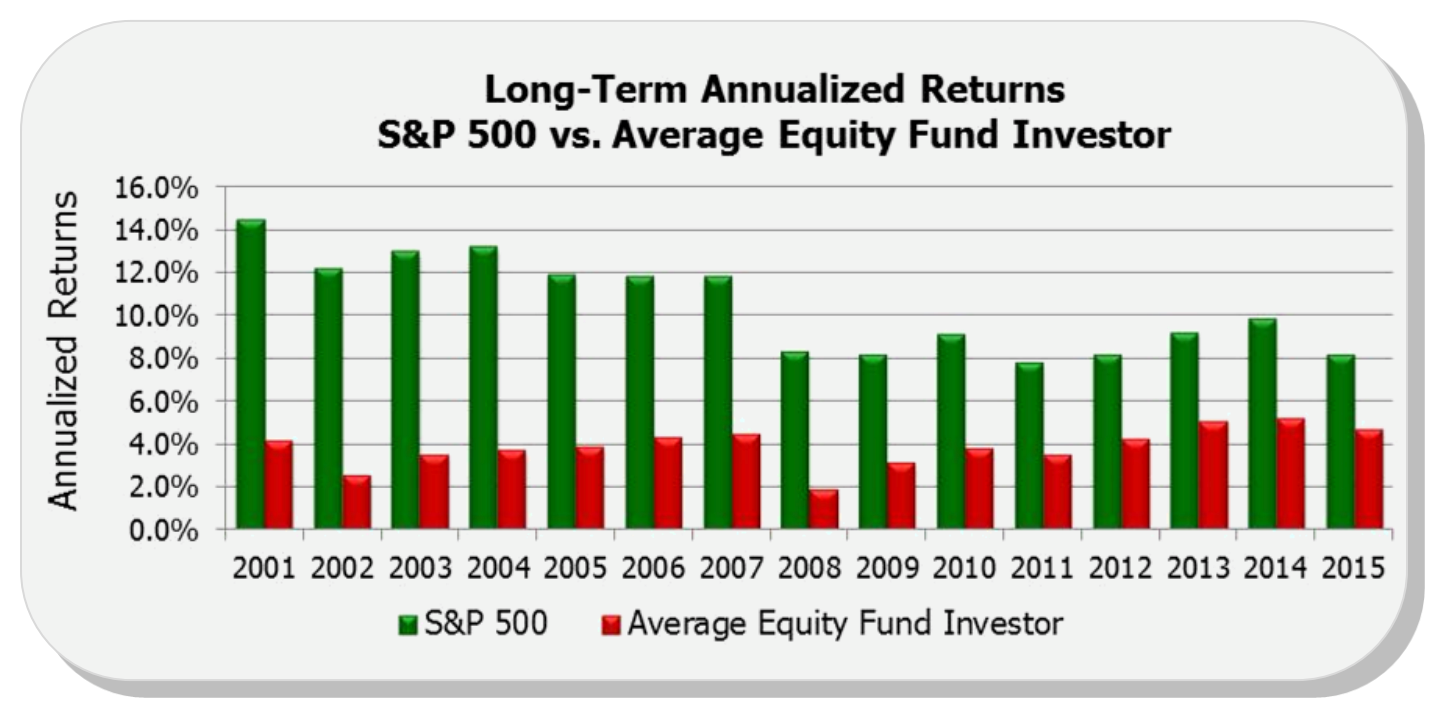

The average investor has always lagged the overall market as illustrated below. Why is this?

By any measure, equity returns have far outstripped those from bonds and property in almost every country around the globe over the very long term.

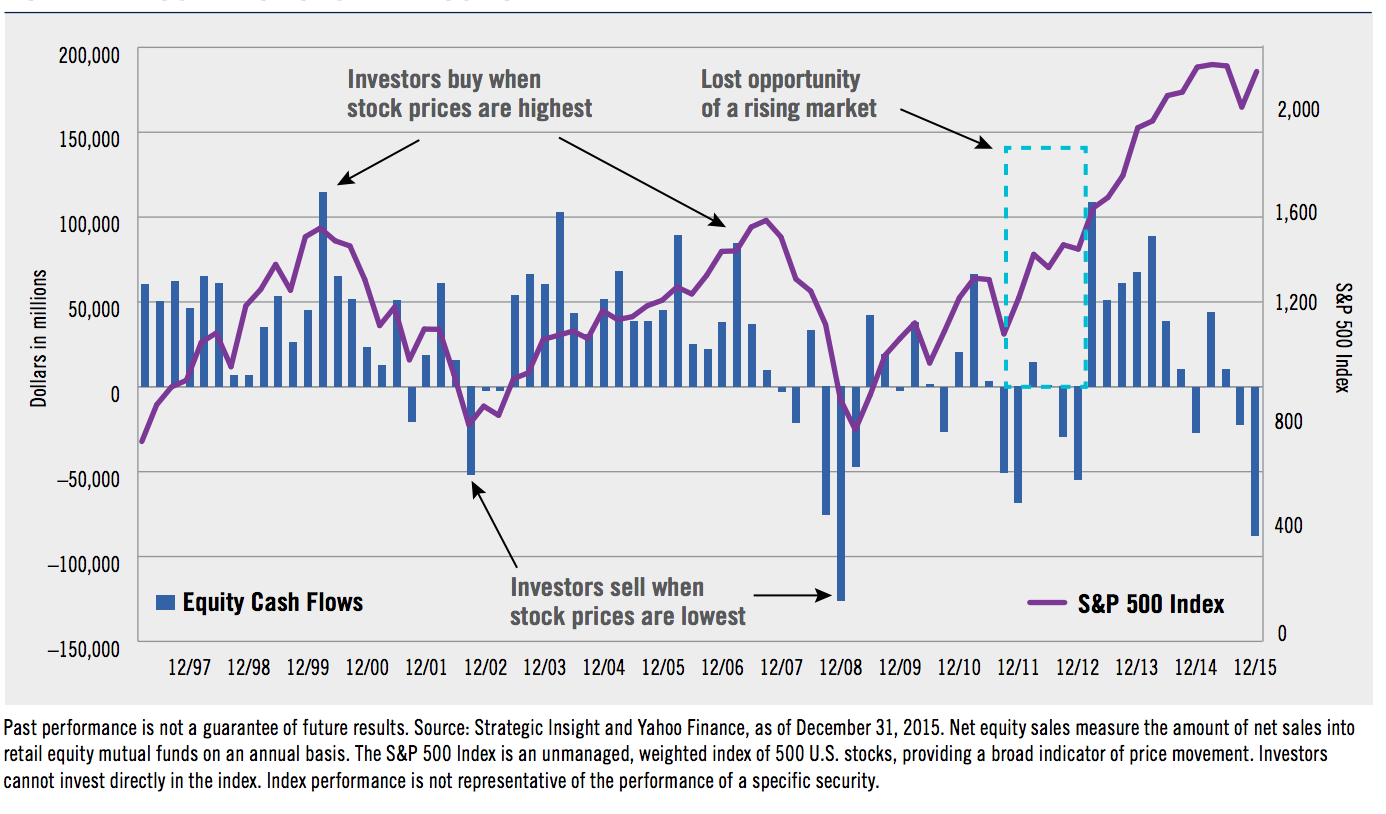

Every investor wants to buy low and sell high, but most investors do exactly the opposite because investment decisions are often driven by emotion. Investors get excited when the market’s rising and everyone else is buying. And of course the flip side, they panic and sell when the market is trending down. This behaviour leads to poor outcomes.

DALBAR’s research revealed that the problem is not the returns of the funds. The reported stated, “Analysis of the underperformance shows that investor behaviour is the number one cause.”

“An investor’s goal is to maximise capital appreciation while minimising capital depreciation. The average mutual fund investor has simply not accomplished either goal.”

Investors who try to time the market and invariably get it “badly” wrong, baling out under stress during downturns and piling in when market strength makes them optimistic as the chart below demonstrates.

Just who is the “average investor?”

The DALBAR QAIB states the average investor refers to “the universe of all mutual fund investors whose actions and financial results are restated to represent a single investor.”

Why does the average investor underperform?

According to DALBAR’s QAIB “Investors may only have themselves to blame, investors make poor investment choices that hurt their investment returns.

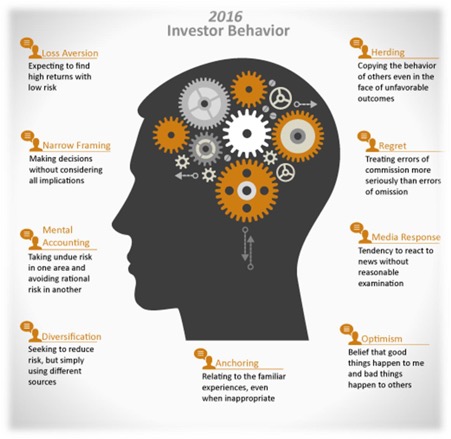

There are nine distinct behaviours that tend to plague investors based on their personal experiences and unique personalities.

- Loss Aversion – expecting to find high returns with low risk.

- Herding – copying the behaviour of others even in the face of unfavourable outcomes.

- Narrow Framing – making decisions without considering all the implications.

- Regret – treating errors of commission more seriously than errors of omission.

- Mental Accounting – taking undue risk in one area and avoiding rational risk in another.

- Media Response – tendency to react to news without reasonable examination.

- Diversification – seeking to reduce risk, but simply using different sources.

- Anchoring – relating to the familiar experiences, even when inappropriate.

- Optimism – belief that good things happen to me and bad things happen to others.

You can see these behaviours in an infographic below.

“Conventional financial theory suggests that investors are rational and seek to maximise their wealth through objective, non-emotional investment decisions. That makes sense. Nobody invests with the goal of losing money. However, the emotions of fear and greed, along with herd instinct, have long been thought to be the main drivers of markets and investor behaviour and lead to irrational investment decisions. This thinking has given rise to the field of behavioural finance.

“Behavioural finance is the study of emotional phenomenon displayed by investors, such as “regret and pride.”

“We saw the regret and pride response in action beginning in March 2000, the largest purchase of mutual funds in the history of the stock market. Fast forward to 2008, just before the “Great Recession” market downturn, and stock prices were falling, but investors refused to sell at a loss. As the market continued to fall, investors held off until they simply couldn’t take it any longer. Many sold their stock near the bottom and missed the following upswing that began around March 2009.

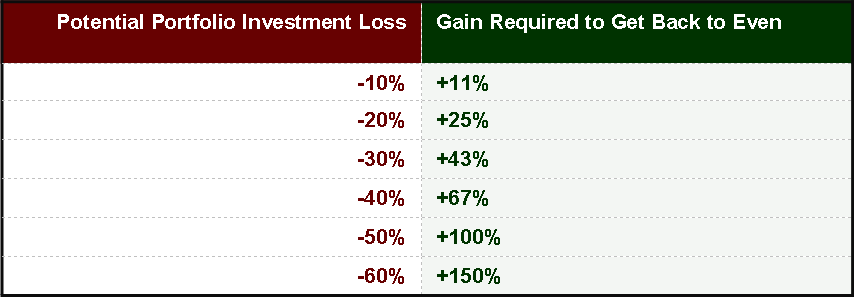

“What many investors may not realise is just how difficult it is to then make up that loss. For example, a 50 percent loss would require a 100 percent gain just to break even — a concept known as negative compounding.

Table 1.

“Investing your own money is a very difficult thing to do. To properly invest, you need to emotionally detach yourself from your money. This is more than many investors are capable of doing.

“Investors incapable of removing their “gut feelings” from the equation can hire an advisor or money manager. But the investor may then find themselves second guessing their advisor and perhaps searching for another. As the market heads back up, the investor feels satisfied with their new advisor — until the next downturn. The whole process will begin again and later repeat itself. This behaviour makes it difficult to achieve personal investment goals and a life of financial independence.”

One thing that all the negative behaviours have in common is that they can lead investors to deviate from a sound investment strategy that was narrowly tailored towards their goals, risk tolerance and time horizon.

The best way to ward off the aforementioned negative behaviours is to:

- Set clear, realistic, long-term goals

- Keep investing, regardless of market fluctuations

- Diversify – don’t put all of your eggs in one basket

- Select quality investments with professional advice

Why overcoming your fear is vital

Finally, it is worth considering how profitable it can be by ignoring all of the market’s vicissitudes over nearly 100 years.

Consider the US IPO of Coca-Cola in 1919 at $40 per share. “A year later the stock was trading at $19.50 – the result of rising sugar prices and a perpetual contract Coca-Cola had with its bottlers to supply syrup for $1 per gallon. What would have happened if your grandparents or great-grandparents purchased a single share in 1919 at $40 and held on through the subsequent decline to $19.50 in 1920, – then on through the great crash of 1929, the subsequent depression of the 1930s, World War II, a baby boom, dozens of other wars and skirmishes, an oil crisis, assassinations, the fall of the Berlin Wall, yuppies, innumerable recessions, booms, busts and scandals, as well as a war in Vietnam, two in Iraq and a global financial crisis? If they kept this share in the family and reinvested all their dividends, they would on 8 January 2010 have 126,321 shares and their investment would have a market value of $6,966,603.15.”

That’s what I wrote in my book Value.able, published in 2010. Since then, however, the dividends have kept on flowing – there have been another 14 in fact – and there was a two-for-one split on 13 August 2012, as well.

By March of 2015, after 14 further dividends and the two-for-one split, and since 8 January 2010, the value of that single Coca-Cola share in 1919 is $11.7 million.

The point is that there has been plenty recently to frighten any ‘investor.’ There’s been QE tapering and fears of inflation, deflation and reflation. We’ve witnessed the Russian incursions into Ukraine, uprisings in Egypt and Europe, a shadow banking crisis and property collapses in China and the threatened annexation by China of disputed territories claimed by Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines. It’s enough to see investors put their cash under the mattress.

And yet, through it all, sound companies with powerful competitive advantages, keep growing their net worth and throwing off rising levels of income.

Conclusion

We trust this paper has convinced you that your own actions may contribute to poor long-term returns. Uncertainties tend to cause us to lose sight of the long-term and focus on the immediate. We swap the telescope for a microscope, and our returns tend to suffer.

Ben Graham, the intellectual dean of value investing said investors should approach investing the way they might buy groceries; buy more when the item is on sale. It seems investors do the opposite of what they need to do to succeed. It also seems investors try and do too much. As the Coca-Cola example shows, picking a great stock or a great manager and doing nothing more, can potentially be a very profitable exercise. Conversely, as DALBAR has proven, too much activity is counterproductive.

So if you are feeling nervous, rest assured you are never alone. But don’t join everyone else in jumping from one boat to another or jumping at shadows.

Source: Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior 2016 examines real investor returns in equity, fixed income and asset allocation funds. The analysis covers the 30-year period to December 31, 2015, encompassing the crash of 1987, the drop at the turn of the millennium, the crash of 2008, plus recovery periods of 2009, 2010 and 2012. This year’s report examines the results of investor behaviour on the average investor and poses the question as to whether an investor’s “best interest” should include investor behaviour. You can read more from DALBAR’s research at: (VIEW LINK)

This White Paper was written by Roger Montgomery as part of the Livewire 2017 Summer Series. To receive Montgomery’s 2017 white papers directly to your inbox sign up here: (VIEW LINK)

5 topics