Why multiples are a short-cut, lazy approximation for valuing a business and what we use instead

This wire was written by Amit Nath, Senior Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments

When you look at a multiple, it may seem high at first glance. But it is essential to focus beyond this and understand the underlying business, its growth opportunities and what current market expectations imply. Certainly, a high multiple can be a red flag for overvaluation. However, you cannot draw any real conclusions from that multiple in isolation.

“That company is expensive because its valuation multiple is high”.

This is one of the most used and repeated phrases of market commentary. In fact, multiples are probably the most enduring pieces of investment analysis of all time.

Unfortunately, they are often completely useless.

The law of the instrument, or Maslow’s hammer, is a cognitive bias where people rely too much on a familiar tool. The renowned American phycologist, Abraham Maslow, articulated this concept with his hammer and nail metaphor.

“It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail,” Maslow wrote.

Multiples are a short-cut, lazy approximation for valuing a business

For many market commentators and armchair enthusiasts, valuation multiples are their Maslow’s hammer, and they apply it indiscriminately – perhaps because it is the only valuation tool they possess in their toolkit.

Valuation multiples are a simplified, abbreviated and short-cut methodology for thinking about the value of a company. They blindly take a company’s price (market cap, enterprise value) and divide it by a fundamental metric (revenue, operating income, earnings per share, etc).

But they don’t tell the whole story or give a complete picture of underlying value and are prone to sizeable error when applied in isolation. And, sadly, multiples have never been less useful than they are today.

If investors can understand how multiples can mislead, and how to value companies in this new complex market, they will be better placed to identify and ride ‘multi-decade compounders’ – the current and next generation of Amazons and Microsofts that build massive long-term wealth.

Multiples were not designed for today’s world

For traditional valuation multiples to be effective, a company needs stable and predictable cash-flows, which are generally found in mature industries like utilities, real estate and infrastructure.

Multiples do a poor job of valuing privileged businesses models that have advantaged economics, including barriers to entry, network effects, and unique datasets.

They also fail to reflect the value of emerging opportunities (aka real options) embedded in the world’s best businesses, including the likes of Facebook’s AR/VR platform and Alphabet’s AI unit.

Multiples provide an inadequate view when companies have high and relatively sustained growth rates, particularly for the world’s best software-driven ecosystems like Microsoft, Google, Amazon or in the alternative asset management space, like Blackstone, KKR, and Carlyle.

Basically, multiples simply break down when investors are analyzing a disruptive company in the midst of an inflection or an industry that is adapting to a new world, a world we are seeing across myriad of sectors such as technology, healthcare, financials, transportation, and energy.

The problem: Humans are very bad at exponential thinking

The core of the problem can be traced back to the fact that humans are very bad at exponential thinking. We prefer to use a simplifying linear concept (like a multiple) for a more complex non-linear concept (high growth business). But we lose information, and that mapping mismatch can lead to errors and ultimately incorrect conclusions.

Google’s world-renowned futurist and Director of Engineering, Raymond Kurzweil, believes humans are linear thinkers by nature, whereas technology, biology and our environment are often exponential.

That, he says, creates enormous blind spots when we pursue higher-order thinking and seek to solve increasingly complex problems.

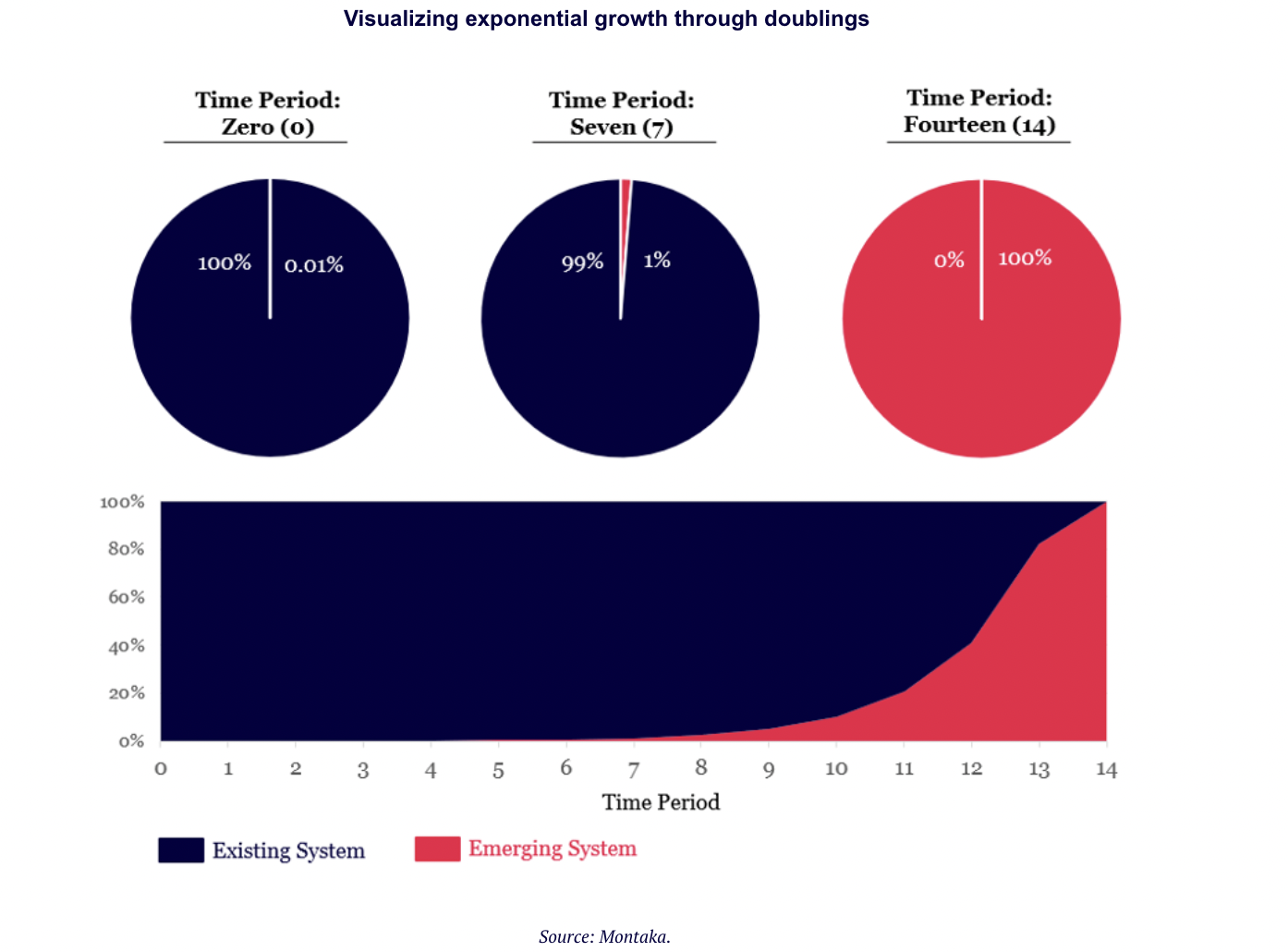

Let’s consider a simple thought experiment often cited as Kurzweil’s law of exponential doublings. It takes seven doublings to go from 0.01% to 1%, and then seven more doublings to go from 1% to 100%. So within 14 time periods, an emerging system has gone from being completely invisible in the linear world (0.01%), to entirely encompassing it (100%).

The Covid-19 pandemic and the exponential spread of the virus gave us a real-world look at what exponential growth feels like as our lives were significantly disrupted. Yet most of us are simply not built to intuitively reconcile this phenomenon.

Multiples meant investors missed massive Microsoft gains

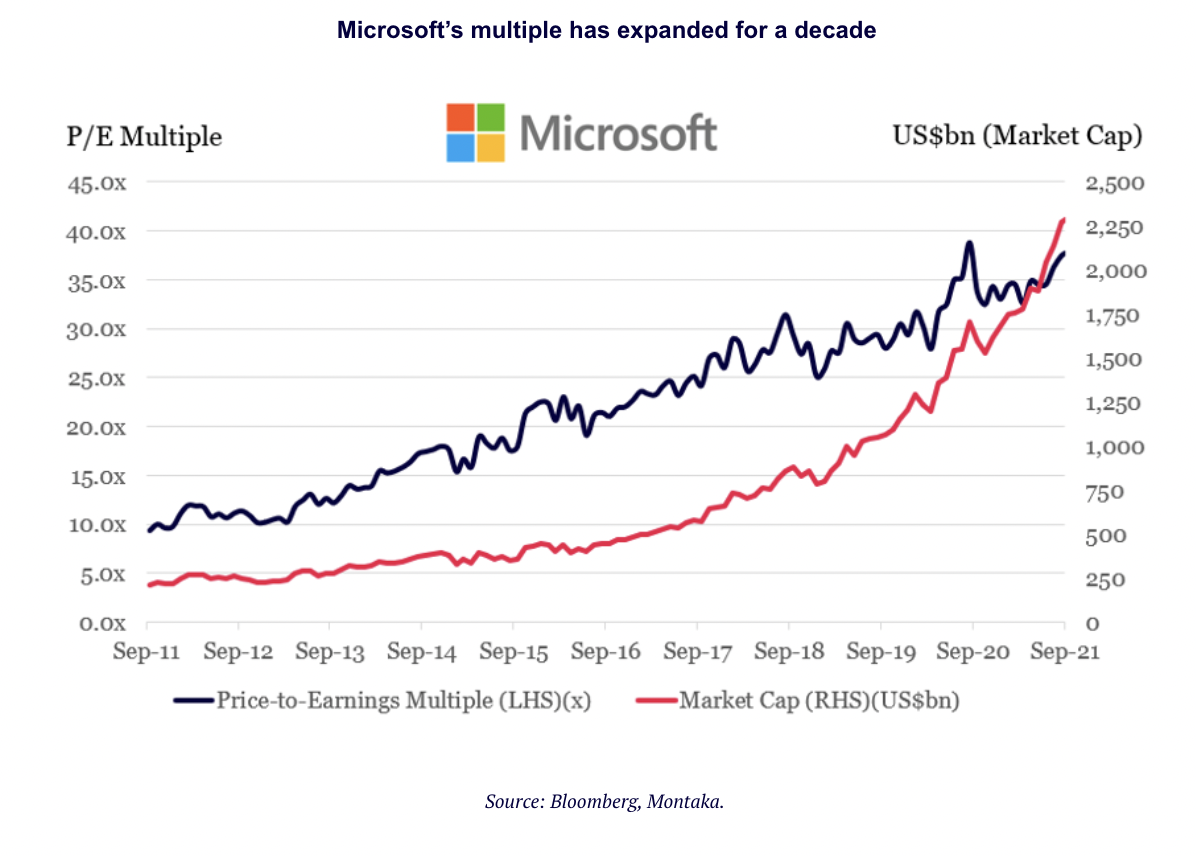

Microsoft is an example of a company where the use of multiples fail. For the last decade, the company has been consistently criticised by some investors for having an extremely high multiple and is on the verge of a sharp pull-back. This narrative continues to persist in parts of the market even today. Yet Microsoft’s multiple has consistently expanded for the entirety of that time.

A linear conversation about Microsoft’s multiple ignores several underlying drivers of Microsoft’s valuation, from its virtual monopoly in enterprise computing (Windows), the stranglehold on productivity applications (Office), to the enormous opportunity ahead of its cloud business (Azure).

Some six years ago Azure was an invisible real option within Microsoft. But it certainly feels pretty real today after growing from basically zero revenue to an estimated $40 billion annualised run-rate (June-2021). Azure continues to grow at around 40-50% year on year with an enormous runway ahead. It demonstrates the exponential growth that many investors still struggle to believe or comprehend.

Another fallacy of those decrying Microsoft’s "high multiple" is that its market capitalisation gains have been entirely driven by multiple expansions and the low-interest-rate environment. Those factors certainly play a role, but multiple expansion only explains a third of Microsoft’s value gains.

While Microsoft’s multiple has expanded four-fold over the last decade, its market cap has increased nearly eleven-fold during that time – driven by a massive earnings inflection and exponential growth within the Azure business. That’s an extremely significant error produced by the unhelpful market heuristic of multiples.

Entrenched habits and lazy analysis have a very long tail and multiples are a seductive short-cut.

How to value companies in today’s complex market

So if multiples mislead, how do investors value companies in this new environment?

The truth is, there are no shortcuts in valuing a business. It is a hard, detailed, and rigorous exercise that takes considerable time and insight to get right.

At Montaka, all our investment theses are fundamentally driven and while not an exhaustive list, we look to gain insights across the following areas:

- Detailed, bottoms-up, DCF (discounted cash flow) assessment of each company we invest in with an exploration of business model economics, TAM (total addressable market), competition, etc

- Top-down perspective of the markets the company currently serves and potentially will serve in the future

- Considerable time is spent considering what the business and industry will look like in 5 to 10 years and what challenges/opportunities may be encountered (this is a never-ending cycle, of course)

- We also establish a set of valuation scenarios that are weighted by the probability of the scenario being reached. They guide our view around upside and downside and colour our level of conviction in the position.

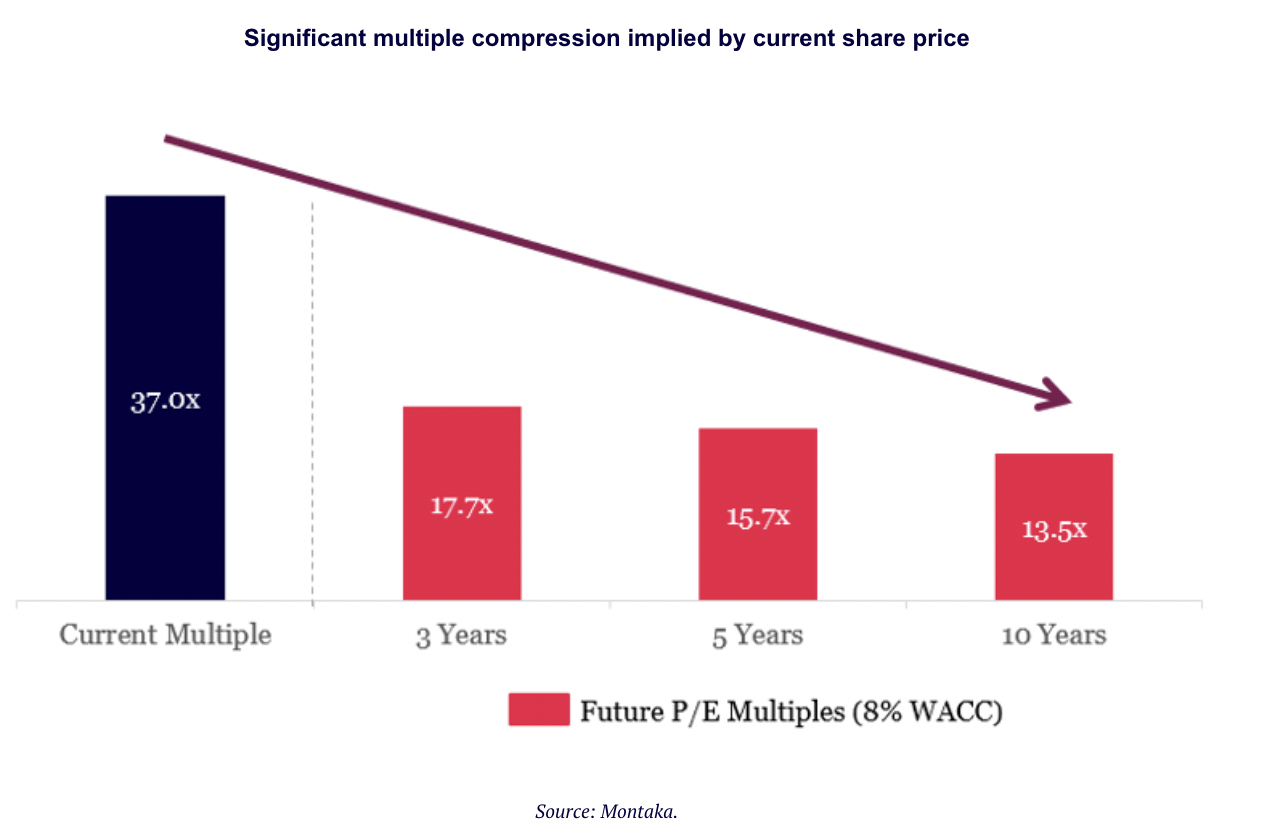

We then effectively take a time machine to several points in the future. For each time period, we observe the multiple our valuation implies.

This helps us check whether we are being too conservative, or too exuberant relative to what the market is willing to pay for the business today. In fact, we often find instances where our DCF has compressed multiples in an unreasonable way or the market is being too conservative with its current price level.

Get comfortable with high multiples

If we continue with Microsoft as an example, the current share price (US$300) implies the market is being extraordinarily bearish on the Azure cloud business, and also believes Microsoft’s future multiple will materially compress over the coming decade.

We strongly disagree with the market’s assessment on both fronts and believe it is significantly underestimating Microsoft’s earnings potential and opportunity set, plus unreasonably discounts the quality of these earnings by slashing its multiple by more than half.

In fact, under our bullish scenarios, we believe Microsoft’s share price could increase several-fold, even from here.

Compounding your wealth over decades

When an investor looks at a multiple, it may seem high at first glance. But it is essential to focus beyond this and understand the underlying business, its growth opportunities and what current market expectations imply.

Certainly, a high multiple can be a red flag for overvaluation. However, in isolation, an investor can’t draw any real conclusions from that multiple. As we’ve seen, in certain situations the current multiple may be outrageously low despite the incessant noise claiming the opposite.

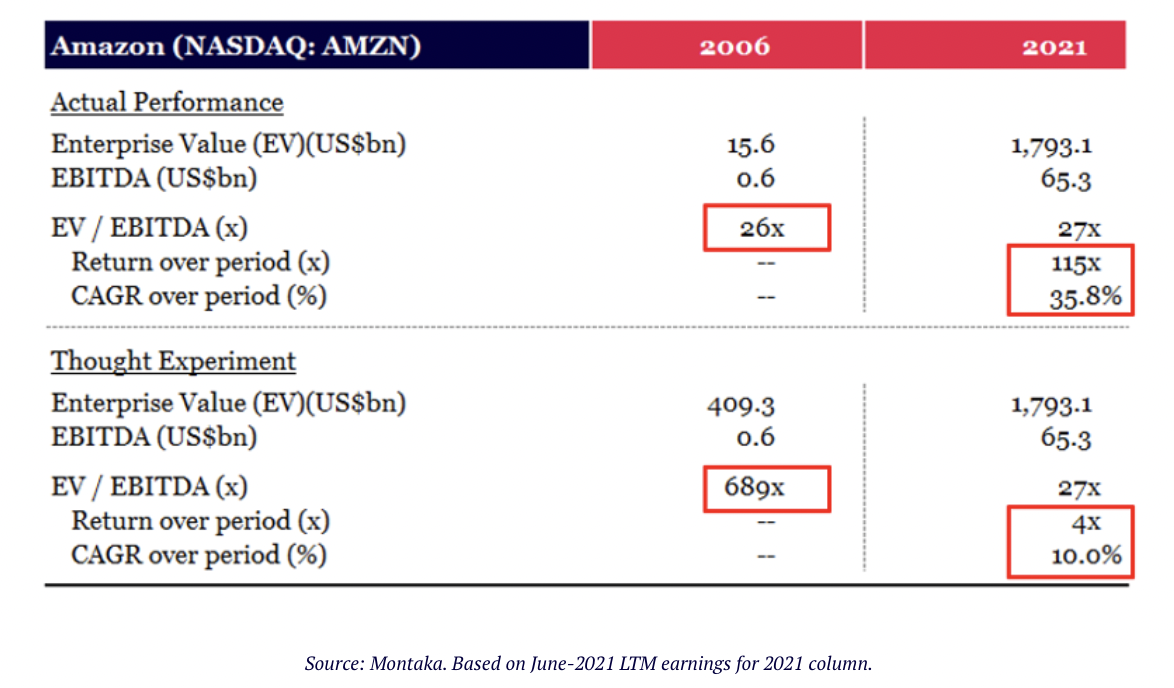

Let's look at Amazon, for example. In 2006, it was trading at an EBITDA multiple of 26x versus the market (S&P 500), which was trading at 10x. Certainly not cheap by typical measures.

But as a thought experiment, if we were to discount the current Amazon enterprise value at an annual rate of 10% back to 2006, an investor should have been willing to pay close to 690x EBITDA and they still would have quadrupled their money today.

The market, however, materially undervalued Amazon and it went on to deliver investors 115x over that period. In fact, you could have paid double the share price for Amazon in 2006 and still made nearly 60x your money today.

At Montaka we have a single clear goal: to maximise the probability of achieving multi-decade compounding of our clients’ wealth, alongside our own.

We are convinced that the months and years ahead will present opportunities to make attractive, multi-generational investments and we are prepared and well-positioned to take advantage of these.

To achieve that, we won’t let multiples become our Maslow’s hammer!

Montaka owns shares in Microsoft.

Compound your wealth over the long-term

Montaka Global Investments provides investors with the opportunity to compound wealth over the long term through disciplined global investment strategies and a sophisticated approach to risk management. Get in touch with us through the 'CONTACT' button below.

4 topics