You are underestimating your equity risk

This insight covers two key questions about how starting valuations affect future outcomes:

1. What can starting valuations tell us about the next 1–2 years beyond just the average (mean) return?

2. Do share markets revert to fair value at the same speed whether they are expensive or cheap? Or in other words, when prices are really high and they fall meaningfully, or really low then rise a meaningful amount, does it happen at the same speed whether they’re going up or down?

Valuation is the relative price paid for assets compared to what it has been over time. It is typically calculated by dividing the price by a measure of the assets worth. The most common version of this for stocks is the PE ratio, or Price-to-Earnings ratio. The ratio tells you how much you’re paying for $1 of earnings from the company or basket of companies. Therefore, when it is high, you’re paying a lot, and when it’s low, you’re not paying nearly as much.

1. What do starting valuations tell us about short-term outcomes?

One of the biggest risks facing higher-growth investment portfolios today is the elevated valuations of large US companies (often referred to as “mega caps”) and the broader share market. The key word here is risk, not return.

It’s well-established that over the long term (10 years or more), the valuation of a market is one of the strongest predictors of future returns. But what’s discussed less often is how current valuations influence short-term risks—such as volatility and sharp price movements over the next 1–2 years.

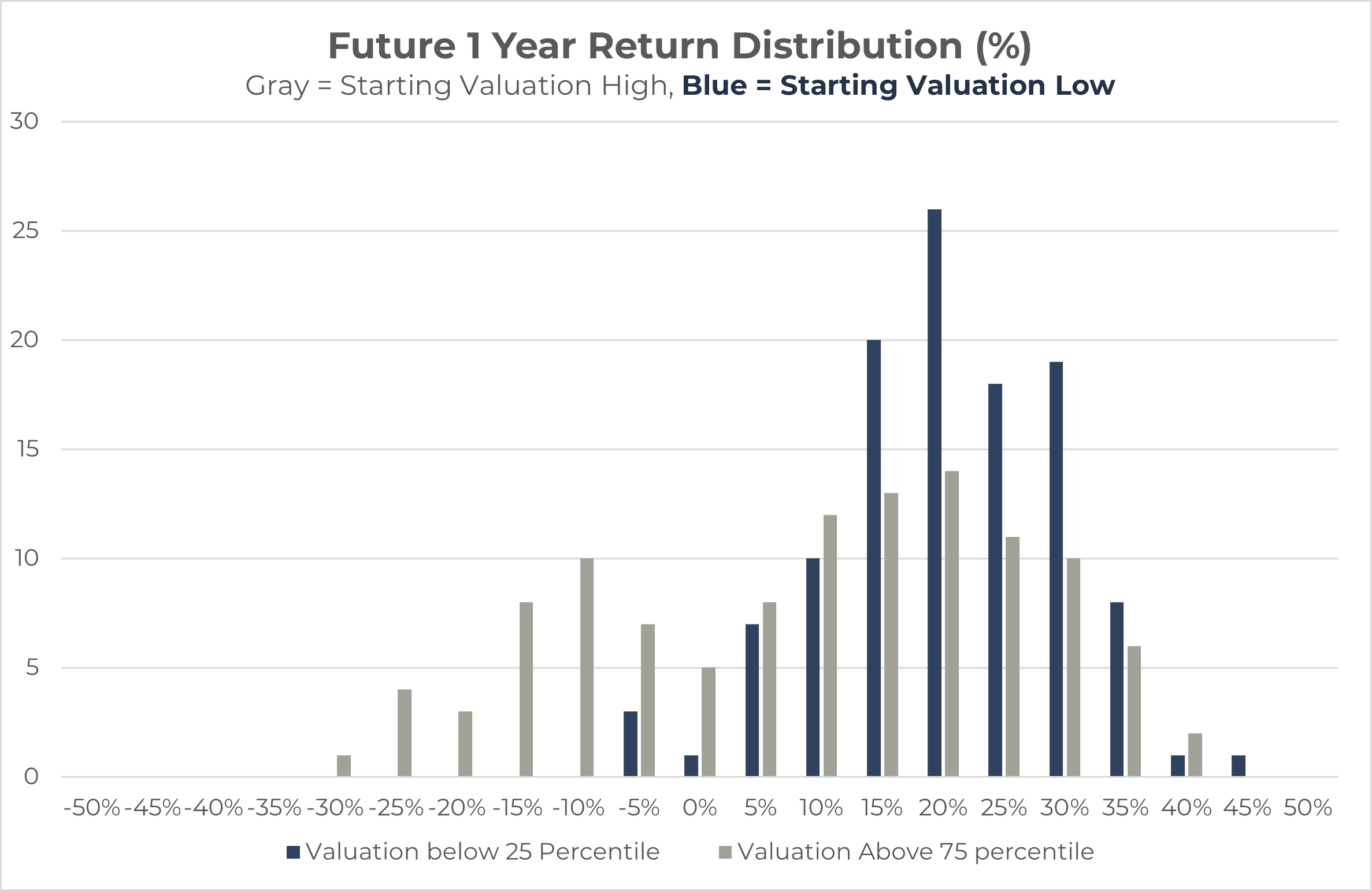

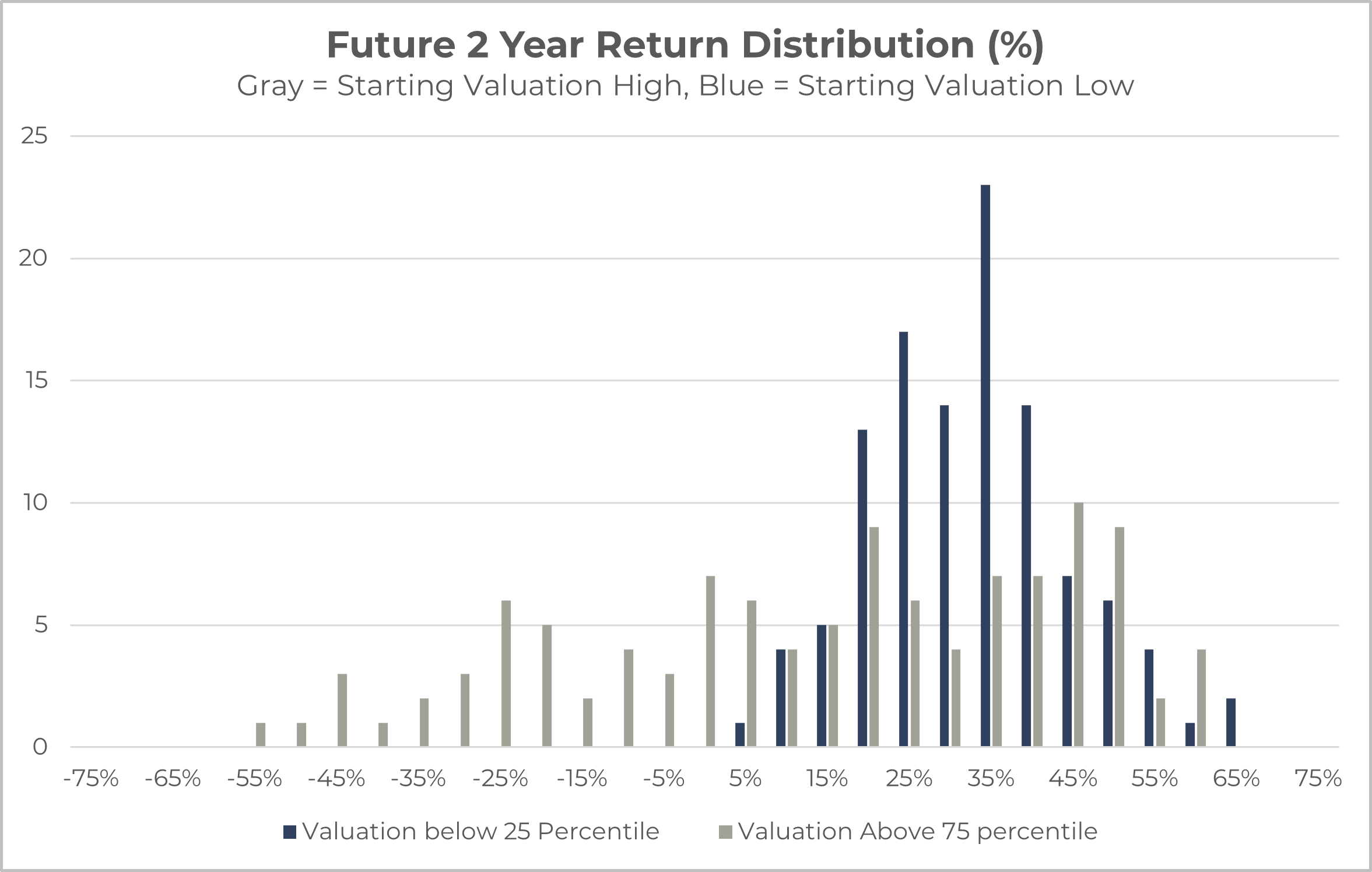

While valuation isn’t particularly useful for predicting what the average return will be over the next year or two, it has been historically useful in assessing the range of possible outcomes—how volatile returns might be and how ‘skewed’ they are (for example, whether there is more downside risk than upside).

This is important for investors aiming to maximise returns without taking on excessive risk. Many investors who follow passive share market indices are now heavily exposed to highly valued stocks, which increases short-term risk, even if they’re unaware of it.

At present, the S&P 500 (a key US share market index) is sitting above the 95th percentile in valuation, based on the Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings (CAPE) ratio. This means it is more expensive than it has been 95% of the time since records began.

When looking at data from 1977 to 2024, we find that:

· When the S&P 500 is cheap (bottom 25% of valuations), future 1-year returns average around +20%, with relatively low volatility.

· When the market is expensive (top 25%), the average return is lower and the range of possible outcomes is much wider, meaning there is a higher level of uncertainty.

2. Do markets revert to fair value the same way when expensive vs. cheap?

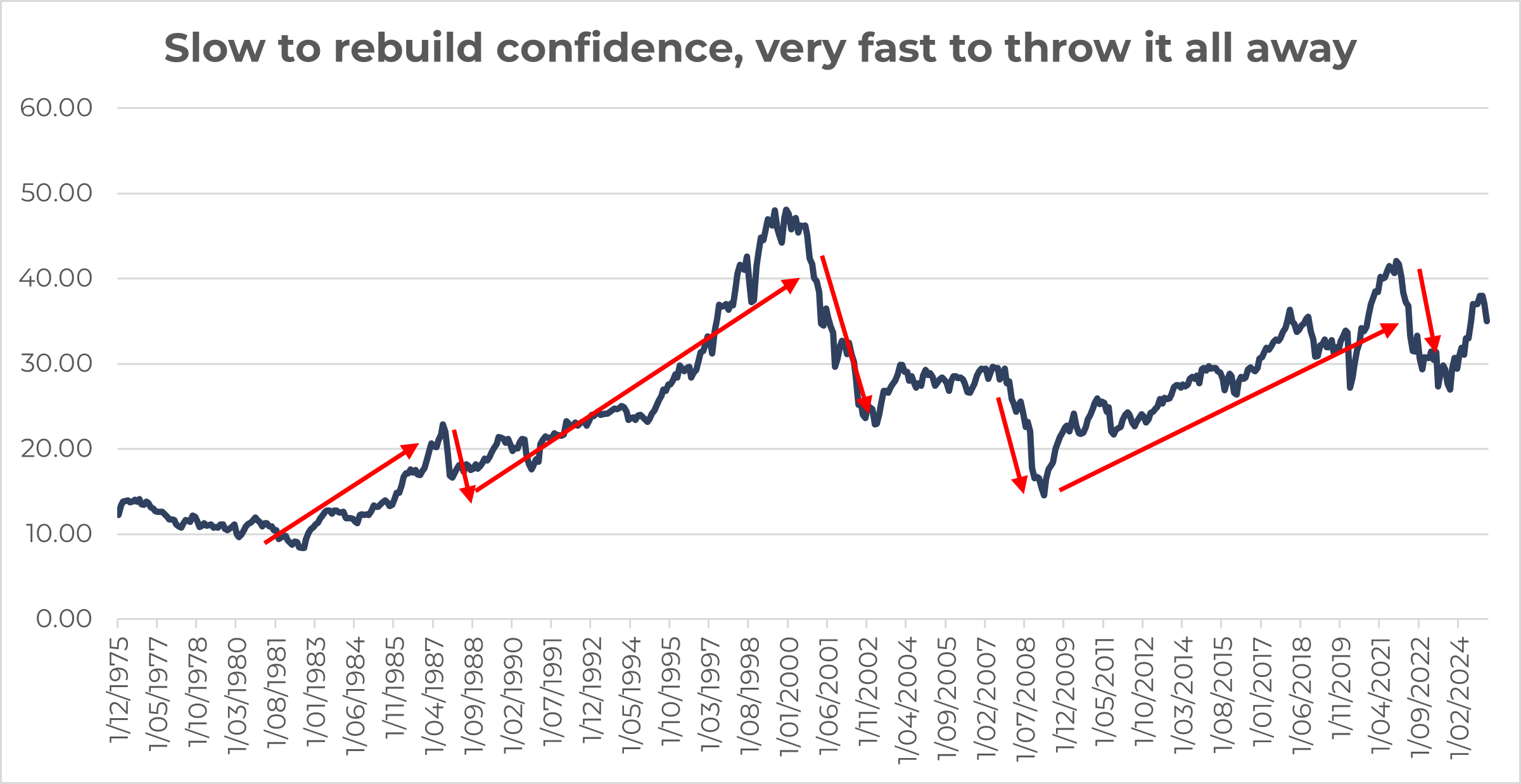

Markets behave very differently depending on whether valuations are high or low.

When markets are undervalued (cheap), investors tend to be cautious, and it often takes time and consistently good news for confidence to return. Recoveries in this phase are usually slow and steady.

However, when markets are overvalued (expensive), corrections tend to be faster and more severe. This is often triggered by panic selling or a sudden need for liquidity—such as during financial crises or major economic shocks. Below are just a few examples of the contrast in velocity dependent on whether valuations are rising or falling:

Source: Bloomberg, Shiller, Innova AM

This pattern has repeated time and time again. Valuations tend to rise slowly as confidence rebuilds, but when fear enters the market, reactions can be sharp and swift. Recent market pullbacks, driven by concerns like trade tensions and slowing US growth, have hurt the most expensive sectors the hardest—proving how sensitive these areas are to bad news.

The takeaway

Buying assets that are attractively valued (i.e. cheaper) not only offers better long-term return potential, but also typically comes with lower short-term risk.

With the S&P 500 currently sitting at a historically expensive level (above the 95th percentile), we believe the range of future outcomes over the next year or two is likely to be much wider than usual.

In this environment, it’s important to look beyond the traditional large-cap benchmarks. Other regions, sectors and investment styles are offering similar earnings growth—often at far more reasonable valuations.

For long-term investors, this reinforces the value of active asset allocation, risk management and thoughtful diversification, rather than simply following market cap-weighted indices.

5 topics