Are US Treasuries no longer a safe haven?

In all the chaos of the past few weeks in the world of financial markets, the most alarming development has been the rise in US bond yields, even while stock markets plummeted and risk aversion skyrocketed.

Even when credit ratings agency, Standard and Poor’s, downgraded the US’s credit rating from AAA to AA+ in 2011, US yields fell along with other risk assets. That means that investors were buying bonds, despite the supposed reduced creditworthiness of the US.

So, what is going on? If a US credit rating downgrade wasn’t enough to shake US treasuries status as a safe haven, what is it about Trump’s policies that is?

Or is this just an alarmist view which is making a mountain out of a molehill?

There are some simple reasons for why bond yields may have spiked earlier in the month, and it may not have much to do with deeper concerns with the status of US treasuries.

One is that in extreme risk averse events, some safe-haven assets are sold off because there’s just greater demand for cash. On one or two of the more panicked days, even gold prices fell, and there’s no question about gold being the ultimate safe haven.

Another valid reason is that despite the heightened recession risk, the potential inflation risk from Trump’s tariffs is limiting the ability for the US Federal Reserve to cut rates. Risk of inflation and higher interest rates than otherwise are likely to put upward pressure on bond yields.

But at the same time, it’s no secret that the US fiscal position isn’t great.

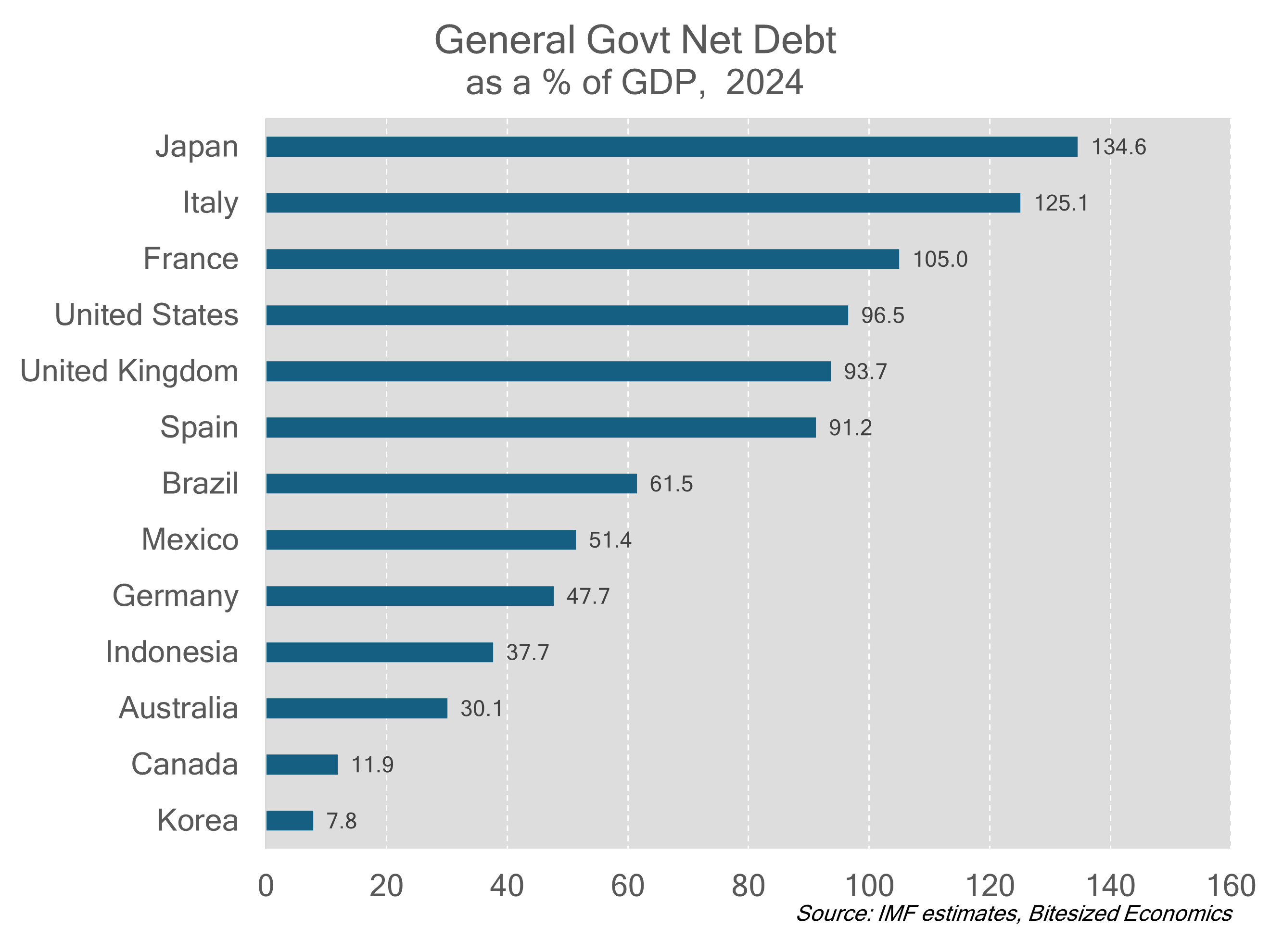

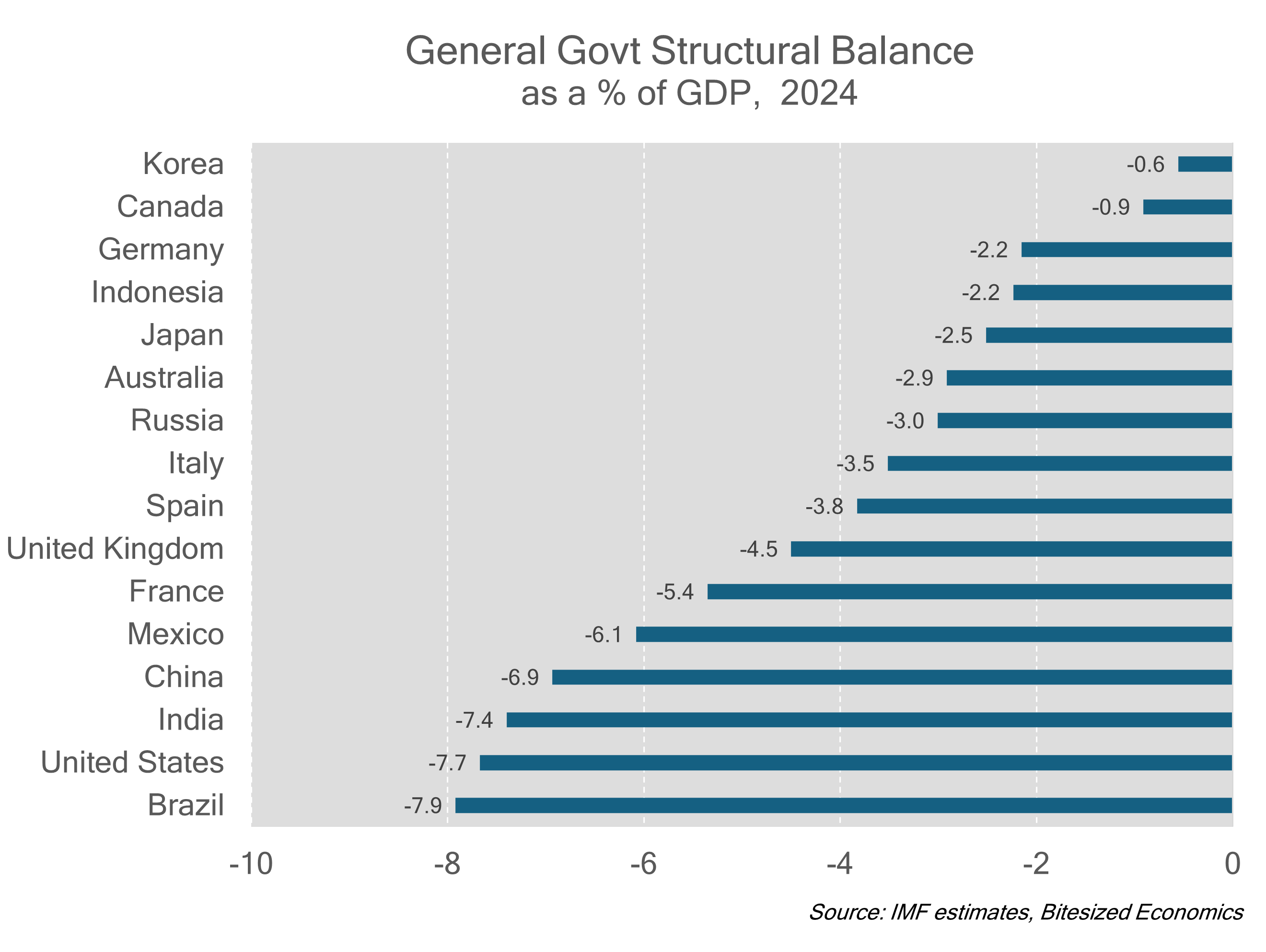

Net debt is set to exceed 100% of GDP in a few years’ time. What’s more, is that the budget trajectory shows deficits as far as the eye can see. There’s no question that both net debt and the budget deficit are large in comparison with other major economies:

Economists don’t have much of a consensus on how much debt is too much for a government. Argentina and Greece defaulted with net government debt at around 150-160% of GDP. But it isn’t just a story of government debt. Net government debt poked above 160% of GDP in Japan in 2020, but Japan’s current account surplus means that there isn’t a lot of concern about it. That current account surplus means that the rest of Japan’s economy can fund its government debt with its own national savings.

The US has a big current account deficit, not a surplus, which means unlike Japan, that government debt needs to be partially financed from offshore, as well as a large government net debt and more budget deficits to come. It has what economists’ call a twin deficit issue (both a current account and a government deficit).

But we’ve all come to accept that the US is a unique case because of the US dollar’s reserve currency status. It’s ok that the US has a government deficit and current account deficit, because the US dollar is a reserve currency.

So, what if, and this is a completely hypothetical case, the US dollar was no longer a reserve currency? Is it the only reason that the US can run both current account and government deficits without investors saying, “hang on, do I still want to lend to this government”? And what makes the US dollar a reserve currency anyway?

Here’s a quote from Fed Chair Powell back in 2023: “We are the world’s reserve currency… that’s because of our democratic institutions, it’s because of our control over inflation over many many years… world trust, and the rule of law. It’s the place where people want to be in times of stress”.

You can see the worry here. Trump’s actions over his first 100 days as president actively undermined the reasons why the US dollar was the reserve currency to begin with. When the US government is the cause of stress, when there is an assault on democratic institutions, when policies are at risk of being inflationary, and when there is a loss of world trust, then the world loses its reasons to make the US dollar the world’s reserve currency.

But there’s also another reason that the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. It’s because many economies around the world still choose to manage their exchange rates against the US dollar, and because many of those economies have maintained surpluses and build up their foreign exchange reserves so that they can manage their currencies. Those economies have to hold US dollar assets, namely US treasuries.

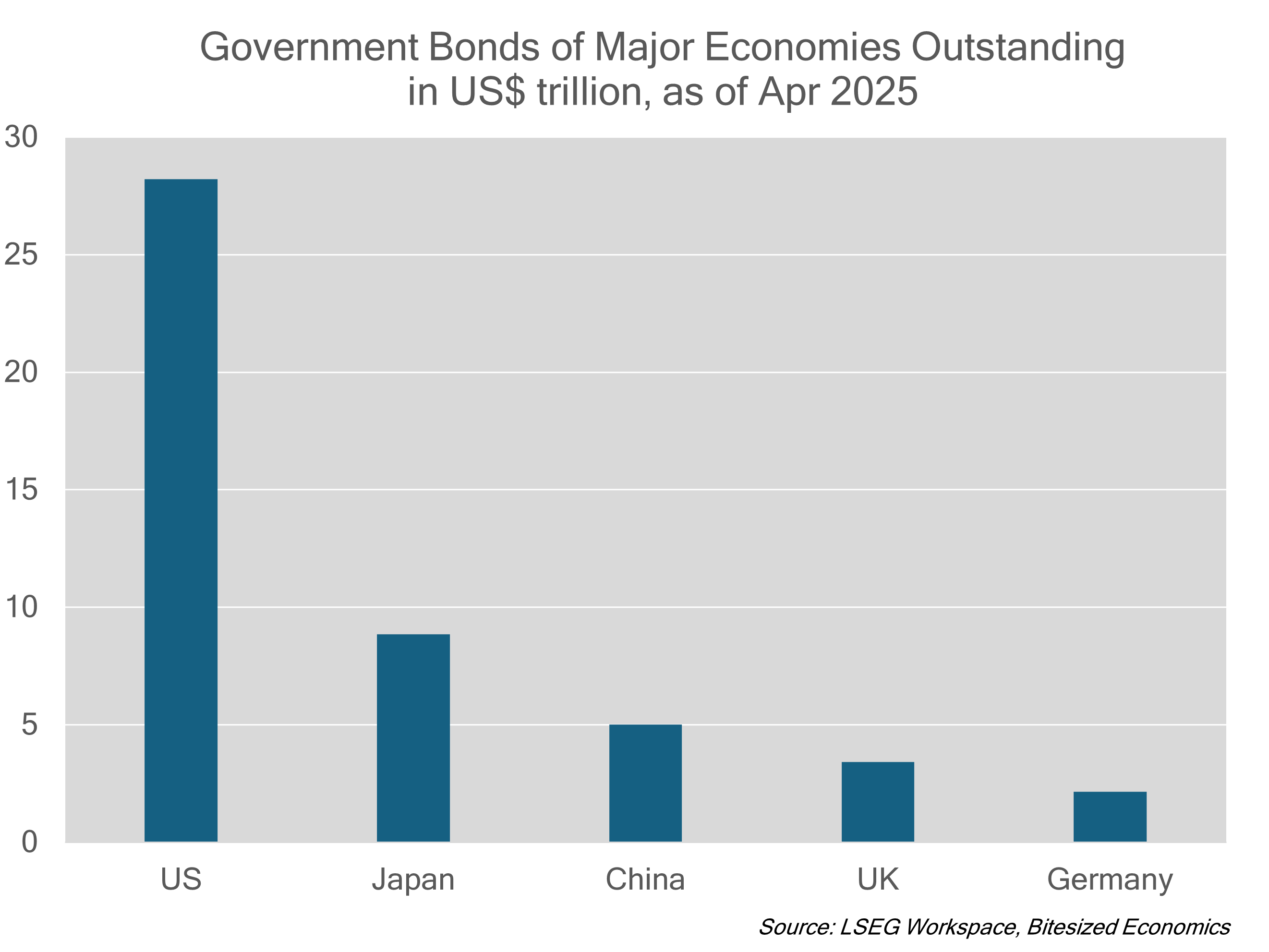

And there’s a final reason that the US dollar is the world’ reserve currency. US capital markets are still the biggest and the most liquid in the world. It also isn’t just governments which hold US treasuries, it’s also investors, both foreign and domestic which hold US treasuries, and they are integral in pricing a whole bunch of other assets in the economy around the world.

There’s no other market that comes close to replacing it. Take the market for Japanese government bonds – with approximately 8.8 trillion US dollars’ worth outstanding. That’s less than half the size of the US treasury market, and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) holds just under half of those holdings although that’s reducing.

So, where do we go from here?

Rising US government debt combined with a widening current account deficit does not seem like a sustainable situation. But equally, without fundamental shifts in surplus economies to lessen reliance on production and exports along with opening their capital accounts, there’s nowhere to turn, as there’s nothing like the US treasury market.

A best-case scenario is that economies get together and find a multilateral solution to reduce global imbalances at some point.

Interestingly, the above comments from Powell about the US dollar’s status as a reserve currency were in response to a question from JD Vance. Vance suggested that the US dollar’s status as a global reserve currency was acting as a tax on American producers and a subsidy to American consumers and was the cause of the hollowing out of American manufacturing.

That isn’t quite true. It isn’t because the US dollar is the global reserve currency. It’s only because now, we have emerging economies reluctant to run current account deficits as they don’t want to risk capital flight triggering currency crises. It’s because emerging economies have benefited most with growth models that favour production over consumption. And so, the US with the US dollar as the reserve currency, has acted as the largest deficit country, has taken up that role of being the major consumer of the world. Finally, it’s because emerging economies as a group are becoming much larger as a proportion of GDP.

The idea that the US reserve currency and global imbalances as being the cause of manufacturing jobs disappearing in the US also ignores the role of automation and robotics which have replaced human labour in modern manufacturing today.

It does make you question whether JD Vance wanted the chaos based on a misguided thought process.

At the end of the day, it was Trump, not Vance, that blinked, which is reassurance that maybe breaking the US financial system wasn’t part of the plan, if there was any plan at all.

As much as the current global imbalances seem unsustainable, it’s in no one’s interest, not the US, not any of the economies that hold US treasuries and have or the rest of the world to break it, especially without anything else to turn to.

The good news is that US yields have come down in the past few days. Trump has attempted to pull out the jenga block from what makes up the global financial system, but the wobbles in the system has stopped him. The question is, does he try again to yank it out again? And is it too late for him to put the piece back in?

Investment Implications

There is no other alternative to the role of US treasuries and the role of the US dollar as a reserve currency. And as chaotic as policy has been, the fact that Trump backtracked sends an important signal that he doesn’t want to break the US financial system.

Moreover, speculation that Japan or China, or any other government which holds large amounts of US treasuries, are going to sell on mass seems farfetched. Such an action would severely undermine their own economies by boosting their own currencies and hurt their own exports at a time when they need that support most.

But that doesn’t suggest that US treasuries are a bargain. Near term inflation risks are very real, from the tariffs themselves and the supply constraints by bringing merchandise trade to a halt, even if temporarily. There’s also Trump’s tax cuts and potential pressure for increased defence spending now that geopolitical tensions have escalated, which could raise further doubts about US debt and inflation, even if economic growth concerns work the other way.

5 topics