Magic and Mistakes in Mining Services

My father used to take me to the horse races as a child. It became something of a father-son thing over the years – usually expensive but always entertaining. It never mattered which horse won. Dad had “looked at it” and “shoulda backed it”. It happened so often we started calling him “coulda shoulda Johnson”.

Good but coulda been better?

The finishing touches are being applied to our 2017 Performance Report. It has been an excellent year, with the Forager Australian Shares Fund returning 25% net of all fees and the International Shares Fund returning 27%, despite adverse currency movements.

One of the big drivers for our Aussie fund was a motley collection of mining and mining services businesses that collectively delivered more than 12% of performance for the year.

As Dad might put it, we coulda and shoulda done better.

We got plenty right in the space. The whole idea was to buy a basket and we fully anticipated some of those basket constituents performing poorly. There was a common theme among the errors, though, and there is a general lesson to be learned.

Understanding the capital cycle

On a recent plane trip I read Capital Returns, Investing Through the Capital Cycle. The book is a collection of Marathon Asset Management’s investor letters edited by Edward Chancellor. It would be much better were the letters rewritten as a standalone book, but the concept is so important I would recommend you read it. Marathon have made wonderful returns over the years shorting industries (and even entire economies) when a flood of new capital leads to low or negative future returns. On the flip side, they have had as much success identifying industries where low recent returns led to a dearth of new investment, which presaged a dramatic increase in profitability once excess capacity was absorbed.

This approach works best in capital intensive industries like mining and mining services. And it was the philosophy behind our investment in mining services stocks between 2013 and 2015. Having overinvested in the boom times, the theory went, a lack of investment in new equipment would eventually lead to a return to industry profitability

What we failed to anticipate, however, is that the adjustment process requires some violence.

Imagine a guy named Bob who runs a drill rig business. The boom times have turned to bust and all of sudden Bob’s industry has too many drill rigs. Trying to keep his head above water, Bob is bidding contacts at prices that only just cover his operational costs.

Nothing shrinks rationally

Were Bob thinking rationally, he would call his mate Ron and say “Ron, we are killing each other here.” “We need to combine your business with my business and park our excess rigs in a yard for a few years until the industry recovers.” A rational return on half of the industry’s capital is better than negative returns on the lot.

Bob doesn’t do that, though. He thinks his business is worth more than Ron’s and that the best approach is to kill Ron rather than merge with him. And the industry turnaround, of course, is “just around the corner”. Bob doesn’t just refuse to merge. He buys more rigs, and the industry conditions deteriorate further. Eventually, either Bob or Ron goes bust, and only then does the industry begin the journey to earning a decent return on capital.

Unfortunately for us, in the real world it was Bob Hughes of Hughes Drilling and not Ron Sayers of Ausdrill who didn’t survive to see the recovery.

The point here is not who won or lost, though, rather that the most likely path to rational pricing in an oversupplied industry is failure rather than merger.

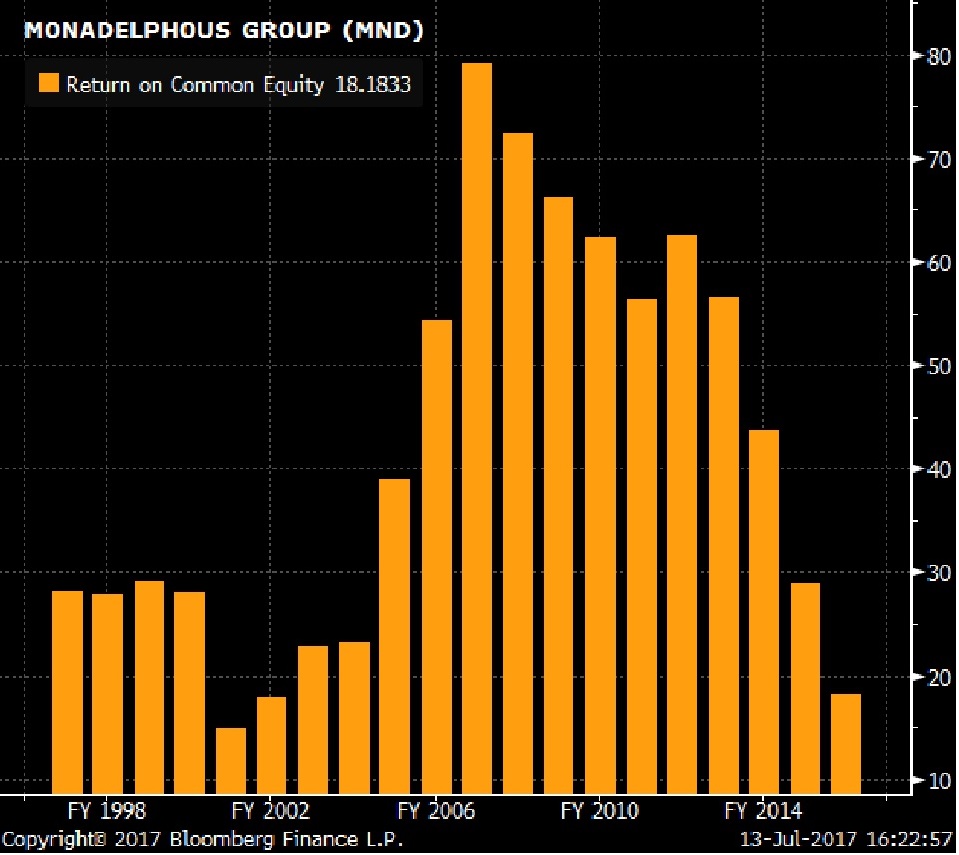

This has important consequences. If the weakest players are almost certain to go broke, the best securities to invest in may not be those that look the cheapest. Balance sheet strength is essential. And, because the pricing gets desperate at the bottom, stock prices for the best businesses can get crazy at the depths. Monadelphous, for example, had a market capitalisation of just $600m in late 2015. This has been an outstanding business for a long time (Monadelphous’s lowest return on equity in the past 20 years was 15% in 2001). It had $200m of net cash and never looked like losing money.

Coulda shoulda I know. But while we were dealing with a disaster, the best company in the sector was available for a song.

Register your email here if you would like to receive a copy.

1 topic

1 stock mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)