October Review: Do You See What I See?

October was one of those months where there was something for everyone. GDP growth for China was 6.7% for the third quarter in a row, it’s amazing what you can engineer in a centrally planned economy. US GDP was solid at 2.9% and Europe is creating some positive economic surprises. The glass can be half full if you want to see it that way.

For those of the half empty disposition US labour market conditions are negative and getting worse, with a big drop in job openings. That aligns with difficult conditions for retailers and restaurants as stretched consumers hold back on spending. The main explanations for sluggish US consumer spending are massive increases in healthcare costs, mounting repayments on personal debts and a minimal increase in per capita GDP since 2009. US business investment has been flat since 2012, it’s very difficult for an economy to grow when there hasn’t been much investment.

There are signs of stress in financial markets, but they are being talked down with this time it’s different logic. Bloomberg asked economists for their scariest charts, but many of these were just so-so rather than scary. Some are saying there’s mounting signs of a recession for 2017, but often it’s the same people who have been saying that for a few years now.

The one thing that remains constant is the growth in global debt levels with an increasingly cavalier attitude from governments, corporations and individuals to what this means. Debt pulls consumption forward, repaying debt reduces consumption and investment. It could be six months or six years before the day of reckoning arrives but immutable laws of debt mean that day will come.

Yield Chasing

The recent long tenor debt issues by Saudi Arabia and Italy are both great examples of yield chasing. Saudi Arabia issued $17.5 billion across 5, 10 and 30 year bonds into $67 billion of demand. Some of the proceeds have been used to repay creditors that the country had been stringing out for months. Saudi Arabia has been struggling since 2014 following the oil price collapse. 80% of its government revenues and 90% of export earnings come from oil products. Saudi Arabia’s ruling family had been doling out higher payments to citizens to keep the peace, but an austerity program is now being implemented. This hasn’t impacted the deputy crown prince though as he recently splurged on a $550 million super yacht.

Back in the good times, Saudi Arabia built up $746 billion of reserves from oil exports. However, in the last two years 25% of those reserves have been used to fund budget deficits and to maintain the currency peg. Saudi officials refused to discuss their outlook for oil prices as part of the pre-deal roadshow and that’s not surprising as futures have oil prices remaining below $60 out to 2024. Saudi Arabia needs $79.70 to balance its budget.

In the 5 C’s of credit, character and cashflow are arguably the most important. Saudi Arabia fails both as it has a record of delaying payments to creditors and is likely to continue to run budget deficits. Based on the current burn rate, the reserves of $560 billion would last approximately six years. That might give some comfort to the buyers of the five year debt, but the ten and thirty year tranches need much higher oil prices or deeper cuts to government spending.

At 2% of GDP Italy’s budget deficits aren’t nearly as bad as Saudi Arabia, but its debt to GDP of 133% ranks behind only Japan and Greece. Bloomberg highlighted that this would be 153% if not for the inclusion of the black economy in the calculation of GDP. Italy has short and medium term issues for lenders to worry about.

In the short term, a “no” vote in the December referendum could lead to a populist and anti-European party gaining control. If Italy was to leave the Euro, in what currency would it repay its debts, if it repaid them at all? The referendum will determine whether reforms to the parliament can be made, which would then allow for reforms to the economy. The outcome is considered a flip of a coin at this stage.

In the medium term, the government will need to deal with its bankrupt banks. Monte dei Paschi’s plans to restructure are in shambles with seemingly no answer to the massive gap in its capital stack other than a government bailout. There will be more to follow with Italy’s banks sitting on at least €360 billion of non-performing loans. Fixing the banks could easily add another 10% to the debt to GDP ratio.

Notwithstanding the short and medium term issues there were €18 billion of bids for the recently issued 50 year bonds. Italy accepted €5 billion, with the bonds to yield 2.80%. Many of the people who bid for these bonds won’t be alive when the principal is due, but that’s assuming that Italy doesn’t default first. Given the very long time frame risks include higher interest rates, the election of a radical government, war and the break-up of European Union. Any of these could see debt holders wiped out.

In other yield chasing there’s been a spike in second lien debt and dividend recaps in the US high yield market. Marty Fridson sees high yield bonds overpriced by 2.3 standard deviations with $1.2 trillion of defaults due in the next 4-5 years. Goldman Sachs agrees saying that high yield has rallied about as far as it can with energy and CCC rated credits the most concerning. Two of the big three rating agencies have been called out for inflating ratings on companies engaged in M&A, giving them credit for cost savings or growth that may not arrive.

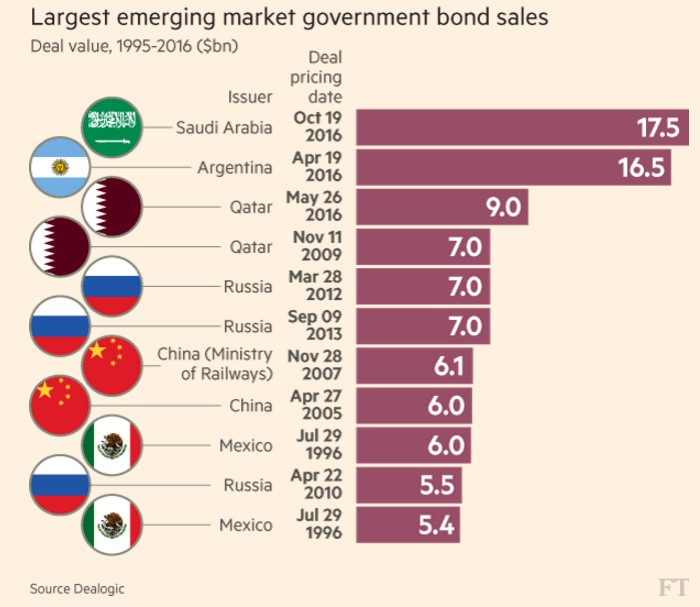

The go-go days are back for subprime home lending in the US, though this time it is taxpayers on the hook with government sponsored entities that assist weaker borrowers making up 30% of all originations. 100% loans are also available in Vancouver. Japanese additional tier 1 securities are trading at a 1% yield and Czech two year bonds traded at -0.94%. Pension funds are taking more credit and duration risk in order to achieve their unrealistic 7.5% return targets. There’s been enormous issuance of emerging market debt this year, even though spreads are near record low levels. The table below highlights the issuance surge with the three biggest emerging market bond sales all happening this year.

Deutsche Bank

I wrote a longer piece this month laying out the logic for Deutsche Bank to go through a bail-in. That piece argues for what I think should happen now when conditions are favourable for a bail-in. What is more likely to happen is that the bank and the German government delay as long as possible, pursuing small ticket changes like paying bonuses in equity or additional tier 1 securities, a hiring freeze, a small capital raising, an IPO of the asset management business and a sale or spin-off of the retail bank. Combining all of those might get halfway to the €40.1 billion of new equity it needs.

The profit of €256 million for the third quarter is a start, but there’s still a long way to go. Whilst the focus is on the Department of Justice fine for mortgage backed securities there’s also litigation over the bank’s alleged failure to act appropriately as trustee after the financial crisis when client losses of $75.7 billion were incurred. There’s the Russian mirror trade scandal and the enhanced repo trades that could see billions more in fines. Doubts remain over level 3 assets and derivatives as the bank has been caught out mismarking these before. Deutsche Bank needs a lot more capital and some clear air to deal with all of these problems. By delaying a bail-in the German government is increasing the likelihood that taxpayers will end up funding part of a resolution for Deutsche Bank at an inopportune time.

China

China’s property prices are growing strongly again producing some interesting anecdotes. Chinese couples are divorcing but not separating in order to bypass government restrictions and buy more property. In a classic bubble era statement one couple noted “if we don’t buy this apartment we’ll miss the chance to get rich”. Vacant land prices in some locations are now more expensive than neighbouring developed property a situation described as “flour being more expensive than bread”. Wolfstreet provided some numbers and graphs to back up the claim that this is the greatest property bubble in history. Zerohedge posted a documentary that showcases ghost cities and US subprime like lending practices. Another article also discussed subprime lending and concludes that China’s property market is set to erupt like Mount Vesuvius in 2017. Bloomberg took a counterview, positing that the lack of land being released for development is the problem.

Debt for equity swaps are kicking off with China Construction Bank said to have 50 in the pipeline. The early reviews of these aren’t good, in one case the company being restructured has reduced debt but has provided guarantees on the returns of the new securities. It is likely that these will be triggered creating another set of liabilities that they can’t pay. Fitch has noted that the process still has many hoops to jump through.

Monetary Policy

The wave of criticism of central bankers hasn’t let up in October with a Barron’s article arguing that central bankers are the truly scary clowns. Politicians have joined in the criticism with Theresa May and Donald Trump calling out the negative impacts of current monetary policy. What has changed is there is something of a fight back based on the concept of central bank independence. I’m a strong supporter of central bank independence, but a strong critic of central bank incompetence. Central bankers that ignore the obvious evidence of asset price bubbles and yield chasing, created by their ultra-low interest rates and money printing, should be sacked just like any other underperforming employee. The questions are who will replace them and what monetary policy should be targeting.

The primary central bank target is typically an inflation level of around 2%. There can also be some vague targets for stable economies (not too hot or cold), economic growth and/or unemployment rates. These add-on targets are unrealistic as central banks are limited to interest rate settings and control of the money supply. These two levers can help to control inflation, but by focussing on trying to boost economic growth central bankers have created instability in financial markets and economies. Truly independent central bankers would have stopped lowering interest rates long ago. They would have told politicians to implement structural and productivity reforms that will help lift economic growth rather than running Frankenstein experiments with interest rates and money printing.

What then should central banks target? The primary focus of central banks should be to ensure that inflation does not exceed a specific bound. The economic and social destruction caused by inflation has been shown in Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe and Venezuela. However, the idea that inflation must be positive should be dispensed as there is no evidence that small levels of disinflation are a problem at all. If your goods need to be replaced, will you go without for long periods simply because they might be 1% cheaper in a year? Even when disinflation is occurring, it will typically be as a result of excess capacity in an economy. Most often this overinvestment originates during boom periods when interest rates are too low.

The arguments against disinflation primarily revolve around debt, as inflation theoretically makes debt easier to repay and disinflation grows the real (post-inflation) amount owed. That argument is both morally wrong and naïve. It’s naïve as when inflation is high investors will usually demand higher interest rates to cover the value lost to inflation. It’s morally wrong as the right way to deal with excessive debt is to face up to it. Excessive debt should be restructured, with the debt owners given the equity in the business or the assets in exchange for reducing or eliminating the debt. If it’s government debt, then investors will suffer for their stupidity in over-lending to governments. There may be some out of jurisdiction assets available to be sold, but government debt effectively ranks behind the provision of services and pension obligations to ordinary citizens.

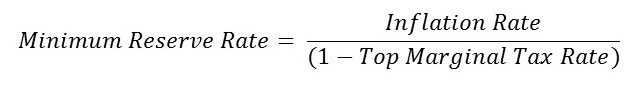

That all points to central banks being tasked with the job of keeping inflation below 3%. I’m comfortable without a lower bound, but some may choose to say the inflation should be kept in a range between -3% and 3%. To incorporate an economic stability element and to prevent financial repression central banks should also be required to ensure that the reserve rate allows all citizens to receive a positive real rate of return. This can be expressed as:

Independent central banks should embrace this rule as it will stop governments from implementing financial repression to deal with budget deficits. It would also deal with the arguments that low interest rates have worsened wealth inequality.

The need to change the committees that set interest rates is also necessary. Some academic economists can remain, but market practitioners who can observe the impacts of rate changes must be brought in. A greater diversity of views is also necessary; there should be voices on the committees drawn from those who are arguing that current rates are way too low. The groupthink amongst the current members at major central banks must be changed if we want to end the cycle of bubbles created by central banks setting interest rates too low for too long.

The arguments by central bankers and academic economists that central bank independence is being threatened is a smokescreen to cover incompetence. Ultra-low interest rates and money printing have created another asset price bubble following on from the tech bubble in 2000 and the sub-prime bubble in 2007. The targets for central banks must change if we want to end this cycle of bubbles. We must lose the false fear of deflation, ensure that citizens receive a positive real rate of return and end the groupthink amongst interest rate setting committees.

Regulation

Most of the time banking scandals are clearly “black” issues, though sometimes there’s both black and shades of grey. BuzzFeed complied a lengthy report on the restructuring department at Royal Bank of Scotland, whose aggressive actions after the onset of the financial crisis led to many borrowers being closed down. This is particularly interesting as it contains black, grey and white conduct. Sometimes amongst the fog of war it can be difficult to tell the difference.

After the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 the Global Restructuring Group at RBoS began aggressively working with borrowers that were stressed and distressed. This would not be of note except that RBoS considered the restructuring unit a potential profit centre and began motivating its staff with bonuses for achieving profitable outcomes. At other banks restructuring staff were generally considered a cost centre and paid far less than sales staff even though their impact on the bottom line can be much greater. What really set RBoS apart was how far their restructuring staff were willing to go to get those bonuses.

RBoS clearly crossed the line when staff conducted dodgy property valuations to trigger loan to value (LVR/LTV) covenants and create defaults. In some cases, the bank then forced property sales at below market values to an affiliated property business in rigged auctions. Bank clients who had complied with their loan contracts were entitled to continue with existing lending facilities. If the clients had obtained decent legal advice they might have been able to fight back against the bank, but as many of the businesses were stretched small and medium sized business they were steamrolled by the bank.

The grey behaviour included misleading customers on their options and concealing conflicts of interest. Some customers were told that their only option was to agree a particular deal offered by the bank when it was possible that other solutions such as raising equity, refinancing or selling assets could have been acceptable. The bank’s solution often involved handing over a chunk of the equity or assets to the bank or an undisclosed related party. Many other lenders took equity stakes in companies they had lent to, but this was typically as part of debt for equity swaps not just as a condition of extending finance.

The white conduct involved increasing the interest rates and charging work fees to clients. The BuzzFeed report cites a case where a property company had breached the LVR covenant and saw its interest rate increased from 1.2% to 4.5% as well as being charged a £485,000 work fee. The property company was under pressure to sell property and was put into a cash sweep to see the debt reduced. On the face of the information presented this is all acceptable conduct as the client had breached the loan agreement.

This case helps illustrate the fundamental misunderstanding many have of the relationship between a bank and a business borrower. The bank lends the money subject to certain conditions and covenants and must continue with the facility for the agreed term providing the client meets the agreed covenants. However, like many contracts, if the customer breaches the contract the supplier has the right to withdraw its goods or services. Covenants are put in place to limit the risk the bank is taking. If the covenants are breached it means that the risk posed by the borrower is higher than was previously the case and the bank is entitled to change its pricing or to completely withdraw the facility.

The big lesson here for business borrowers is to be conservative in their borrowings with banks. In good times, there could be many options if things get tight. But if you breach covenants when there is a recession, your options are very limited. Whilst other restructuring groups weren’t nearly as aggressive as RBoS most did act to reduce their exposures with higher risk borrowers. In Australia, many of the large property groups undertook several rounds of equity raisings which substantially diluted their shareholders in order to avoid breaching covenants. Those who were too highly leveraged lost most or all of their equity value whilst those with little or no leverage were able to buy assets cheaply. An alternative for large businesses is to borrow from the bond markets where bank style covenants may not be required and longer debt terms are available. This gives businesses more flexibility to ride through difficult times.

US Presidential Election

The presidential election is being referred to as the choice between “the lesser of two evils”. Some have marked Clinton as the second worst candidate of all time, with her front-running position only due to Trump being the worst candidate of all time. Trump’s “locker room banter” was widely considered to be the end of the road for his run. Up until last week the press had been giving Clinton something of a free ride with her scandals but with the FBI re-opening its investigation the focus is back on her shady history.

The email issues for Clinton are actually two separate problems. Firstly, Clinton did not follow appropriate protocols in handling classified information. The FBI initially concluded that whilst Clinton had done the wrong thing it wasn’t intentional so she shouldn’t face charges. The law doesn’t mention intent; if you do the wrong thing you are likely to face prison time with a history of others going to jail for this. The deliberate violation of the subpoena that ordered emails be handed over is also dubious. This is where the “rigged” claims come from.

The second thing stemming from the leaked emails is the “pay to play” scandal. There’s substantial evidence that Clinton used her position as Secretary of State to grant favours to those who donated to the Clinton Foundation, paid for speeches given by herself and who did business with her husband. This is where the “corrupt” claims come from.

It is not impossible to see three different possibilities for US President in twelve months’ time. The most likely is Clinton to win and hold the job. But a Trump victory or Clinton winning but then having to step down with Tim Kaine becoming president are also possible. Despite the major parties both putting forward morally bankrupt candidates the Libertarian and Green candidates have received little and attention and will struggle to break 10% combined.

4 topics