Safe as houses? Think again. Big 4 bank shares aren’t worth the risk

Following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Australian financial regulators have presented a sanguine outlook for the Australian banking system.

It is indeed correct to say the US issues aren’t ours. Australian banks typically initiate and hold floating rate loans on balance sheet, and our largest banks have relatively sticky deposit bases. They avoid the same exposure to bond mark-to-markets and the asset liability mismatch that comes from the 30-year fixed rate household mortgage lending that occurs in the United State's highly competitive funding market.

But there’s a great irony in the fact issues that aren't ours have somewhat solidified confidence in Australia’s big banks. Indeed, the crisis abroad has diverted attention from some uniquely Australian issues which place bank shareholders in a vulnerable position.

The great Australian extreme

During COVID, western Central Banks reinforced loose fiscal policy via aggressive pro-cyclical quantitative easing, creating surplus deposits in their respective banking systems which inevitably found their way into lending and in Australia, this led to a boom in house prices.

That over-stimulus also caused inflation to soar. Then the same Central Banks responded with a seismic policy rate shift, the aftershocks of which are now being felt as a major headwind for the economy and banking system profitability.

In the US, the interest rate shock has impacted banks as they absorbed rising rates themselves, with little ability to pass the impacts to households because of their long fixed rate loans. But in Australia the distinct vulnerability lies with indebted households as banks pass on rate rises to customers, balancing credit risk against margin risk.

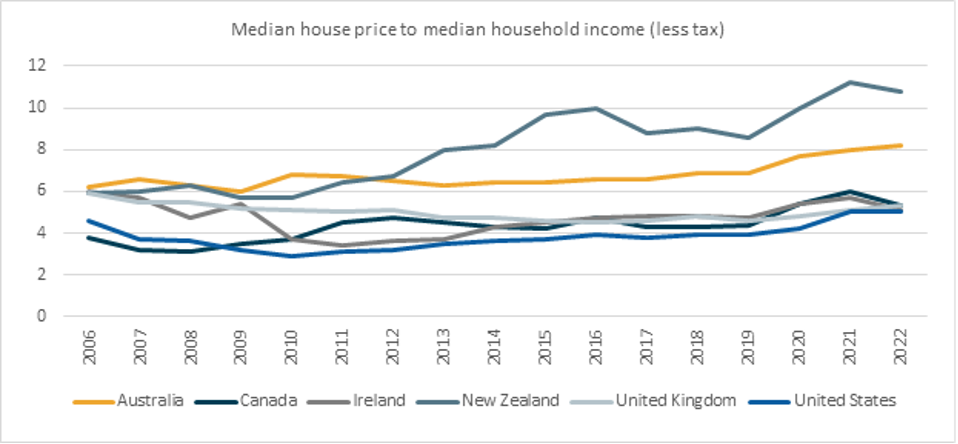

These risks are exacerbated by extreme housing unaffordability versus other developed markets and there is a further concentration risk unique to Australian households - their multiple layers of exposure to residential property via direct holdings and through savings and superannuation funds with a home bias to Australian fixed income and equities.

The Australian banks, which have a very high exposures to residential lending, account for 22% of the local equity benchmark, versus 9% for the global benchmark.

Source: Urban Reform Institute (Houston): International Housing Affordability reports, Morgan Stanley, Antipodes Partners

While it’s not all bad news with banks sitting on considerable reserves of home equity (with average dynamic loan-to-value ratios on loans averaging less than 50% made over many years and at far lower than today’s house prices), entwined within the system are key areas vulnerability.

For example, one third of loans have been made to investors that may have multiple properties. We know that 26% of households are landlords and that 12% of property investors own three or more properties outside their main residence, while negative gearing, along with a bias towards interest-only loan terms incentivises re-leveraging.

Then there’s the issue surrounding extreme gearing - the RBA estimates that 13.5% of households with a mortgage have loan-to-income ratios of above 600% and the median within this cohort is remarkably above 900%.

Underwriting standards of mortgages originated post-COVID is a further area of concern, with around 20% made to borrowers with around 6x debt-to-income and 35% made at loan-to-value ratios of greater than 80%. That’s some 10% of the current stock of loans and at average prices 10-15% above today.

Now this brings us to the much debated and critical question regarding house prices.

Antipodes estimates the restoration of some semblance of affordability requires a further 10-15% drop which will send these loans, including up to 25% of first home-buyer loans, into negative equity and further compound systemic risk by impacting the solvency of mortgage insurers that are vital to the ongoing flow of mortgage credit.

Keep in mind around 30% or $700b of the current stock of residential mortgage debt is on fixed rates of close to 2%, with around half of these written post-COVID and funded by banks via ultra-cheap funding from the RBA. Some two-thirds will reset into variable-rates 300bps or higher by the end of 2023, leading to mortgage payment increases for these households of at least 30%.

The shocks that might cause these imbalances to unwind are difficult to predict.

For now, immigration ensures tight housing markets and prices, whilst negative gearing policies ensure large interest and rental losses can be funded, thereby masking credit issues. However, the excessive escalation of house prices of recent years means this collateral - in the proportion of loans more likely to experience delinquency - is fundamentally riskier than in the past.

Questioning the “unquestionably strong”

Another consideration for investors is APRA’s lenient macroprudential oversight. Overlaid with 30x average leverage on banks’ mortgage books and thin excess capital buffers versus other jurisdictions, there is limited margin of error.

A look at the capital positions of a sample of banks across the world might surprise some Livewire readers.

While APRA is more stringent on CET1 calculations, it is not in setting the absolute minimum – for example, the UK’s NatWest (LON: NWG), Dutch multinational ING (AMS: INGA) and Sweden’s Swedbank (STO: SWED-A) target minimum CET1 ratios that are much higher than the Commonwealth Bank (ASX: CBA) despite having an equally healthy exposure to full-recourse mortgages.

And at the simplest level of bank capitalisation, that is the level of tangible equity to loans, the Australian banks are in fact at the bottom of the pack while also sporting high loan-to-deposit (LDR) ratios, implying higher dependence on wholesale funding.

Our regulator's soft touch oversight has also been evident in Australia's key mortgage-related policy change in recent times - a 50bps increase in the serviceability buffer to 3%, applicable to new lending implemented in late 2021. This implies many loans may have been underwritten at rates close to, or below 5%, and certainly below current mortgage rates.

This incremental protection after an extraordinary decade of house price growth was arguably too little, too late and has potentially created a pro-cyclical system risk as house prices fall.

To contrast, the UK and Ireland implemented a 4-4.5x loan-to-income (LTI) limit on mortgage lending from 2014 with under 10% of loans written since COVID exceeding this. Sweden curtailed interest-only borrowing from 2016, whilst Canadian banks underwrite to an absolute floor rate of 5.25% when assessing serviceability. Nearly all these markets curb the amount of high loan-to-value lending to investors.

Meanwhile, APRA systemically unwound such measures in the years leading up to COVID, all of which would have worked to curtail the affordability scenario that Australia now faces.

The most interesting period is lending during 2020-22 - many of these loans are or soon will be subject to meaningful interest-rate shocks. Only a small portion of these loans need to default for banks’ thin capital surplus over regulatory minimums to be tested and the sustainability of current dividends to be questioned.

This, plus the fact affordability has become materially worse in the last year hampers recovery as lending can only restart with lower house prices or lower rates.

Banks under pressure to increase capital levels and loan loss provisions as delinquencies rise may further hinder lending and stymie a recovery.

Investment risk versus return

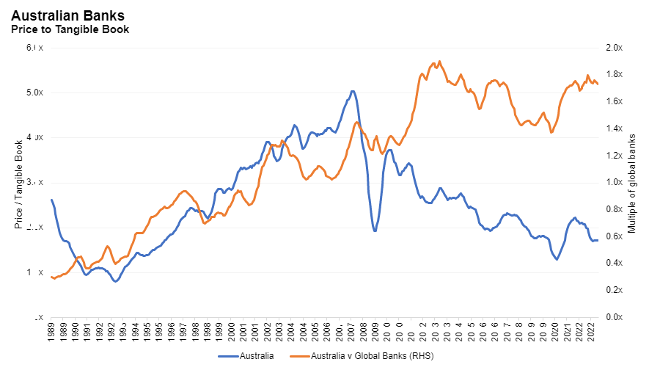

These risks might be palatable for Australian bank stocks if valuations more than compensated for them. But they don’t.

Source: Factset, Antipodes Partners

Against global peers, when measured by price to tangible book, Australian bank valuations have rarely been more expensive. Similarly, adjusted for excess capital, Australian banks trade on a significant premium to global peers; for example, CBA at 16x FY24 earnings vs. European banks at around 7x.

Further, the degree of surplus capital relative to market capitalization is a key measure of a bank’s potential to sustain shareholder returns via dividends and/or buybacks. Any need to bolster a bank’s capital position puts shareholder returns at risk.

On this measure, Australian bank shareholders, especially those seeking dividend yield, are in a vulnerable position.

So while you might have seen the big banks report big profits and big dividends in recent days, don't overlook the big challenges facing our banking system when considering whether to buy, hold or sell.

*Antipodes is short Australian banks as a tail-risk hedge against global bank long holdings and general equity exposure.

Discover more about Antipodes

Antipodes is a leading global equities investment manager with over $10 billion in assets under management on behalf of a wide range of super funds, foundations, wealth managers and individuals.

Discover Antipodes' funds here. You can also follow Antipodes on LinkedIn to keep up to date with the team's latest insights and news.

5 stocks mentioned

2 funds mentioned