The challenge of high and rising public debt

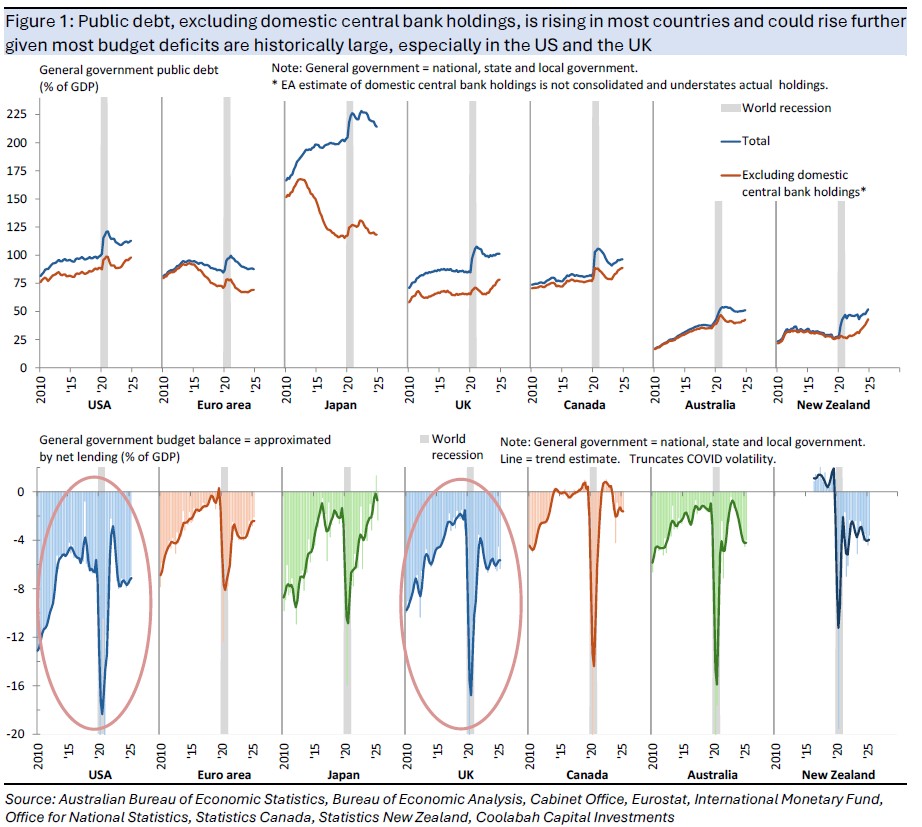

High public debt is common to many economies, with the US, the UK and France in the worst position, running large budget deficits, and where Europe is beset by structural economic problems (Australian and NZ debt is rising, but remains relatively low). Debt is likely to rise further as countries spend significantly more on defence and with history suggesting a recession is always around the corner. There is no short-term solution because there is no political appetite for meaningful budget repair and higher debt has already added to bond yields over recent years.

Public debt is necessary because it is unfair for taxpayers to pay the upfront cost of services/facilities that will be used by future generations. Moreover, too little debt can signify underinvestment by government, which limits the public’s access to education, health and housing.

Across the advanced economies, public debt – spanning national, state and local governments – is high as a share of GDP in most countries, bar Australia and New Zealand, and is rising once domestic central bank holdings are excluded. Japan is a notable exception, with debt falling as a share of GDP, while there are marked differences across the member countries of the euro area.

High public debt matters because:

- High public debt is likely a drag on economic growth. The effect could be non-linear, with very high debt an even larger constraint on activity, although there is lingering controversy over the Rogoff-Reinhart debt threshold of 90% of GDP.

- High interest payments reduce the scope for spending on social services and infrastructure. High debt could also limit a government’s ability to respond to the next economic downturn.

- High public debt raises interest rates, boosting the short-term neutral policy rate and adding to the term premium on government bond yields.

- Some policies aimed at dealing with high public debt – such as engineering high inflation and/or financial repression – can have undesirable side-effects on the economy and financial markets.

Moreover, public debt is likely to rise further given most budget deficits are historically large, stuck well above pre-COVID levels, with the US and the UK in the worst position.

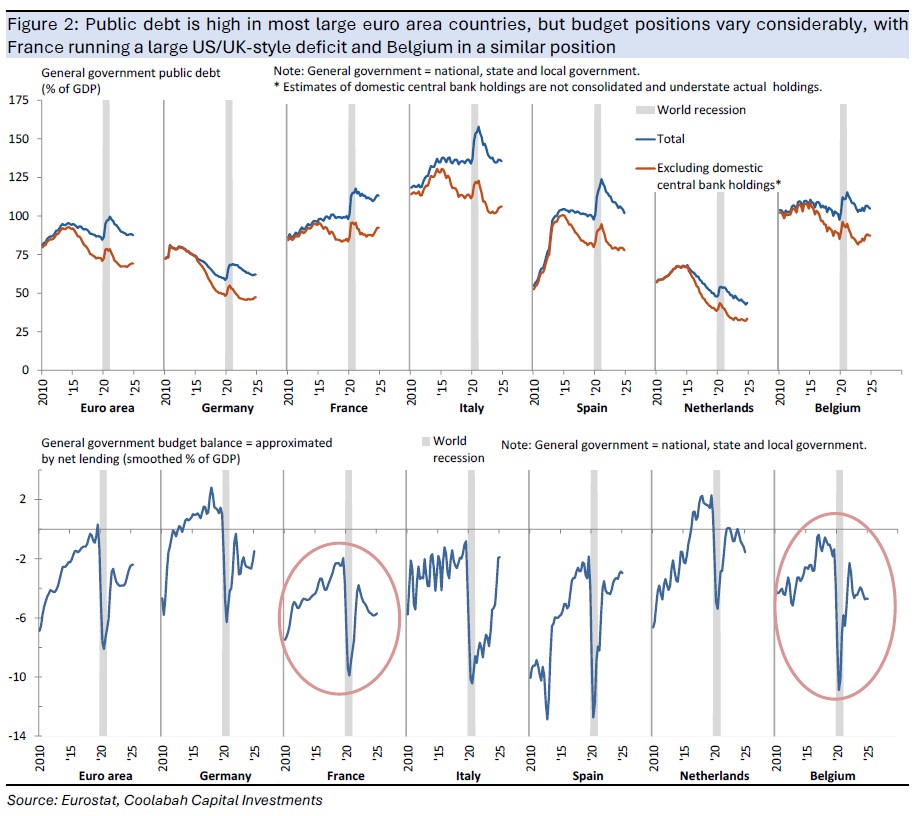

The situation is more variable across the euro area. Most euro area countries – even those with high levels of debt – have either small or modest deficits as a share of GDP. France stands out with a large US/UK-style budget deficit, although Belgium is in a similar position.

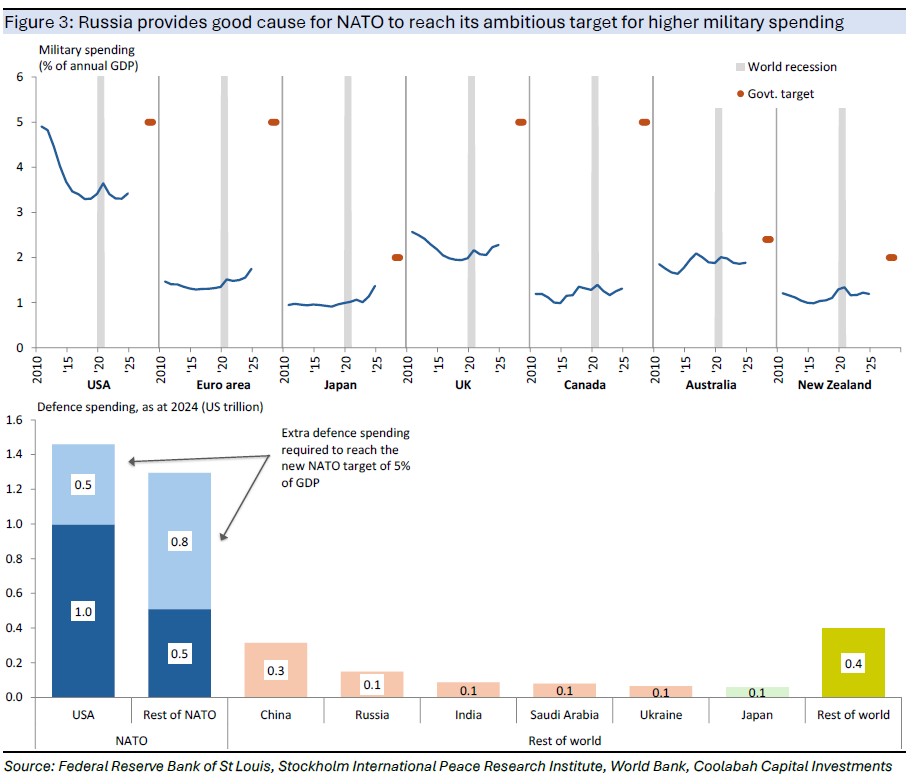

Importantly, all countries face two significant challenges to the budget outlook, one being the commitment to a very large increase in defence spending, and the other that history shows a recession is always around the corner.

At the insistence of the US, NATO members have committed to raising military spending to an ambitious target of 5% of GDP by 2035, where Europe faces a belligerent Russia. Other countries – including Australia – also plan to spend more on defence, although not by as much as NATO.

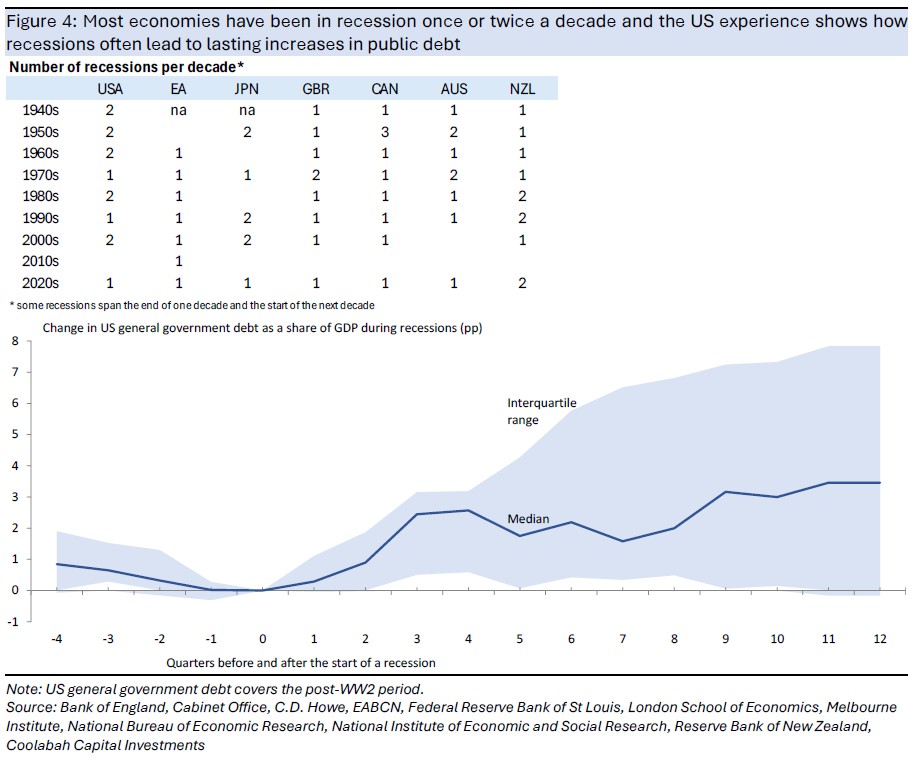

As for downturns, recessions occur more often than people think and inevitably add to public debt.

In the post-WW2 period, advanced economies have generally been in recession once or twice a decade and the last common recession of 2020 differed from past downturns in that it was driven by a health crisis rather than private-sector excesses and/or central bank/government policy.

Not only do recessions increase public debt, debt is usually higher for a long time. For example, US public debt typically increased by 2-3% of GDP in the wake of post-WW2 recessions.

Given these two clear risks to high levels of public debt in many countries, it is unfortunate that the most obvious way of bringing debt under control – namely, raising taxes and cutting spending – is politically unpalatable.

This leaves fallback approaches involving economic and financial means.

Of these, the best option is stronger economic growth driven by productivity. This is because population-led growth has an ambiguous impact on public debt, in that a larger tax take is countered by an increased demand for government services and infrastructure.

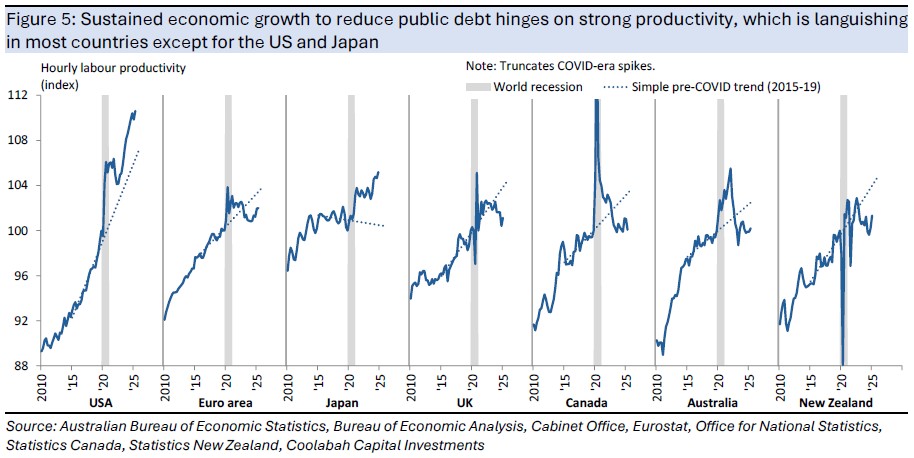

Unfortunately, the news here is not good for the highly-indebted economies of the UK and France because productivity is languishing outside the US and Japan.

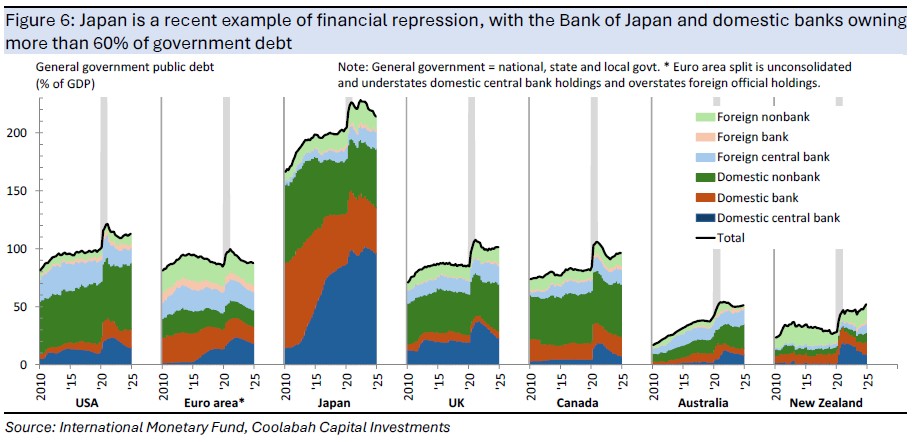

Another strategy for dealing with high public debt is financial repression, which involves forcing the domestic central bank, banks, and/or pension funds to buy government debt. Japan has effectively taken this approach in recent years, with the Bank of Japan and Japanese banks owning more than 60% of Japan’s public debt.

Finally, a riskier strategy typically seen in emerging markets is to hold interest rates too low to generate high inflation to reduce the real burden of public debt. The US could go down this path if the government successfully takes control of the Federal Reserve next year and forces it to adopt artificially low interest rates.

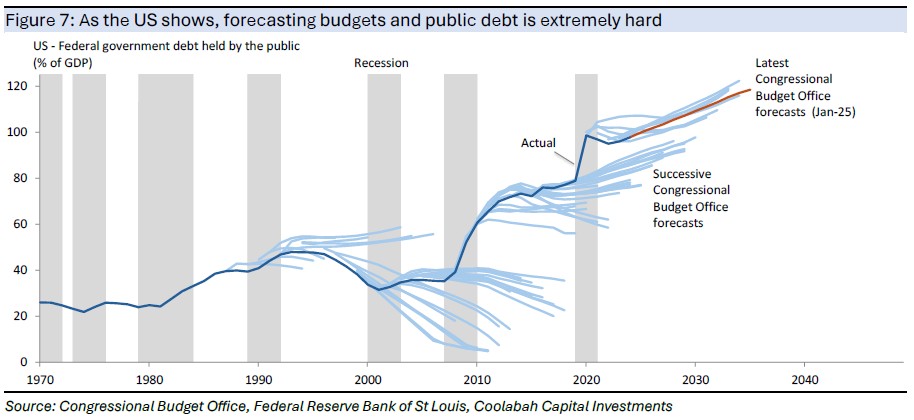

As for the impact of higher public debt on financial markets, markets attempt to be forward looking, but in practice it is hard to forecast budget deficits and public debt because governments change their mind, policy costings can be wide of the mark, and the economy regularly turns out differently.

This is clearly seen in the difficulty the Congressional Budget Office – which is the gold standard in budget forecasting – has in forecasting US government debt, where the forecasts are often wrong and often wrong by a lot.

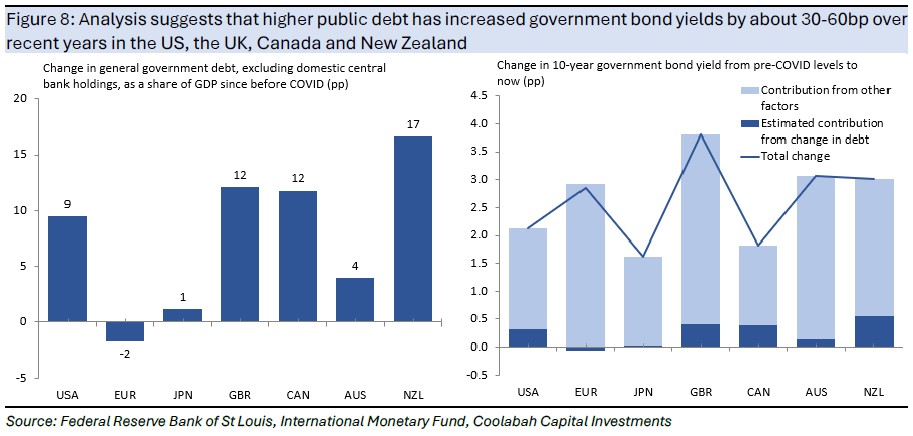

Notwithstanding the difficulty in forecasting debt, the rise in debt over recent years has already contributed to higher government bond yields. Averaging across the results from a range of academic and official studies and surveys of investors, a 10% increase in public debt as a share of GDP increases long-term government bond yields by about 30bp. The largest increases in debt since prior to the pandemic have occurred in the US, the UK, Canada and New Zealand, suggesting that higher debt has already added about 30-60bp to bond yields in those countries, with the risk of more to come for the reasons outlined above.

5 topics