The Fed has built a Maginot line, and there is movement in the Ardennes...

Global Macro

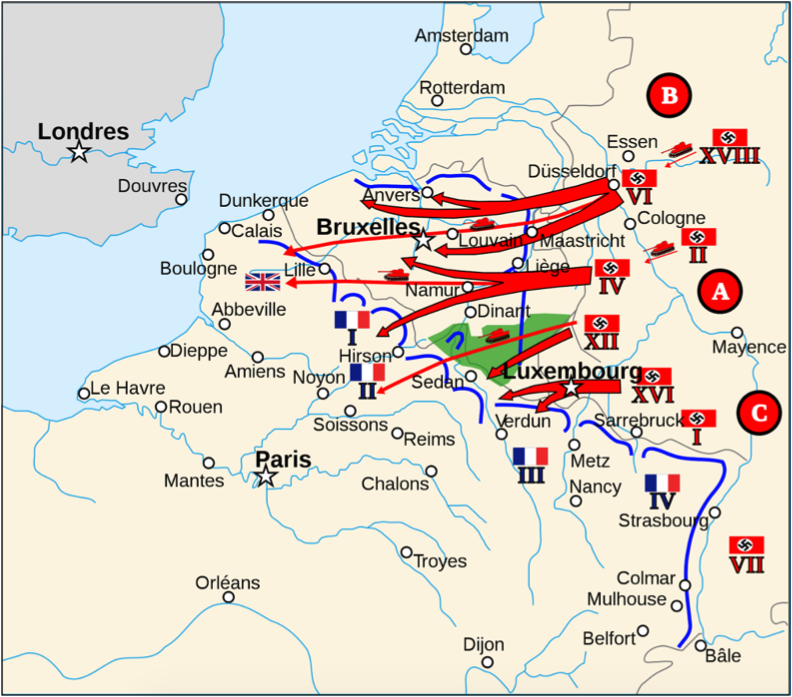

We are all familiar with the Maginot line. A fortified defence on the border of France and Germany, built by France mostly in the 1930’s to prevent a German invasion.

But perhaps not the detail. Fifty large forts, with up to 1000 soldiers each, were built every 9 miles along the border between France and Germany. Between the large forts, were 2-3 smaller forts. Each large fort had the firepower to cover the two to its left and two to its right, if one were to be taken out. The defences were tiered up to 16 miles deep, and finally a mobile army was behind the forts, ready to be deployed to the attack. It was calculated that the fort defence would comfortably hold an attack at bay until the mobile army arrived. Indeed, at the start of the war, the French had roughly the same number of tanks as the Germans, about 2500.

And the Germans simply went around the heavily fortified line, slicing through Belgium and into the north of France.

Sounds pretty silly in hindsight doesn’t it? Why didn’t anyone see this at the time? Well in actual fact the possibility was carefully considered.

The French certainly knew the forest was penetrable. Indeed they had conducted inter-war testing with the Belgians and knew full well tanks could get through the forest. But the French General Maxime Weygand thought it would be impassable, given the terrain and forest, and provided it was properly defended. Indeed, with a major river to cross and all the bridges destroyed, the French believed it would take an armoured division 10 days to navigate the forest. French scouts would give plenty of notice for defence forces to be deployed in the event of an attack. (1)

Sounds fine. Except we know it wasn’t. So what failed in this careful plan? Well, firstly the Germans got through in four days, not 10. Their tanks were able to handle the terrain better than expected. But they crossed the river especially quickly, using pontoons strung along cables. And their more sophisticated communication in the tanks kept the movement organised and faster. Finally, the French scouts miscommunicated, and French high command were convinced the reports of German movements were minor German forces conducting diversions.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Why am I starting with this fabled narrative? Well, the analogies of course. 10 years after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks and regulators are sitting back lauding the creation of a new defence against a repeat of a GFC. They point to a dramatic increase in the capital holding requirements of systemically important banks, a tightening of lending standards, and legislated control of risk taking by banks. A “new Maginot Line”, shall we say.

In addition, financial stability reviews are now common place across the world, the aim of course to prevent a repeat of the GFC. Naturally they consider any possibility that might generate instability. And always they come to the same conclusion. Although there are some potential sources for financial instability in the world, it would take some time and likely evolve slowly enough for authorities to react. Similar to the French conclusion regarding the impenetrable Ardennes...

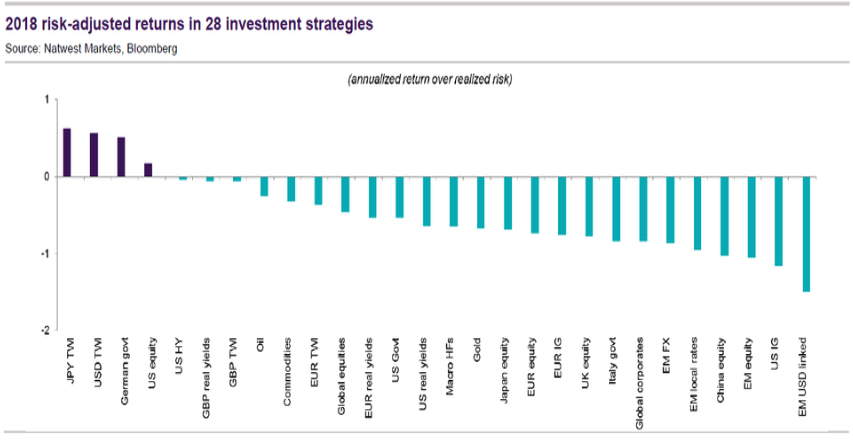

So is there an Ardennes equivalent for financial markets? Yes, there is. But before I go there, let’s first take stock. In short, it has been a dismal year for pretty much all investments.

It is fair to say all portfolio managers have moved to defensive positioning. Capital preservation is the order of the day. Where is the next “attack” on asset value going to come from?

But at the same time, the defensive positions lack conviction. Why? Because US economic data has been essentially fine. Indeed, in the last few weeks we have had:

a) A truce in the China/US tariff battle

b) A US federal reserve indicating they will likely pause after one or two more rate hikes

c) US growth data surprisingly resilient

d) And US inflation and wage data surprisingly benign.

Frankly, one would have thought the combination of the above would have calmed markets considerably, and we would right now be looking at a “climb the wall of worry” grinding “Santa Claus” rally in equity markets And yet, as I write, following a benign employment update in the US on Friday 7th December, the US equity market is on its knees.

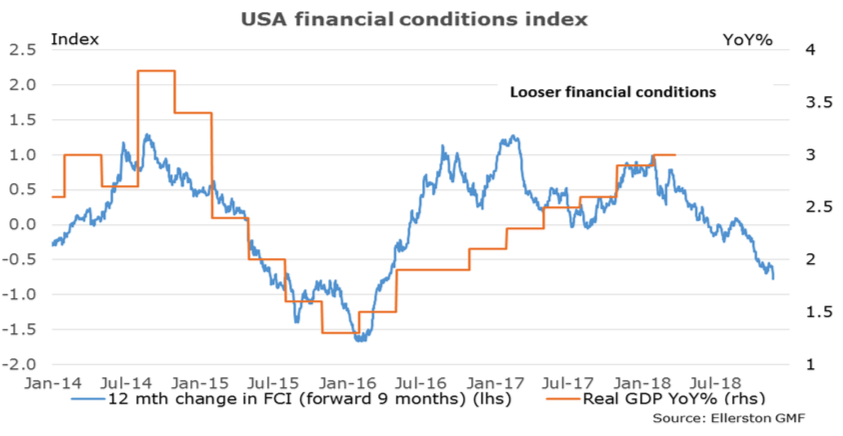

So what gives? Last month I wrote about the tightening in financial conditions in the US (measured by our FCI), and how this would weigh on the growth outlook for 2019.

We felt more tightening would still be required. But we were somewhat agnostic on what would drive that tightening. More likely it would be the Fed, but it could reasonably be wider corporate bond spreads and weaker equity markets.

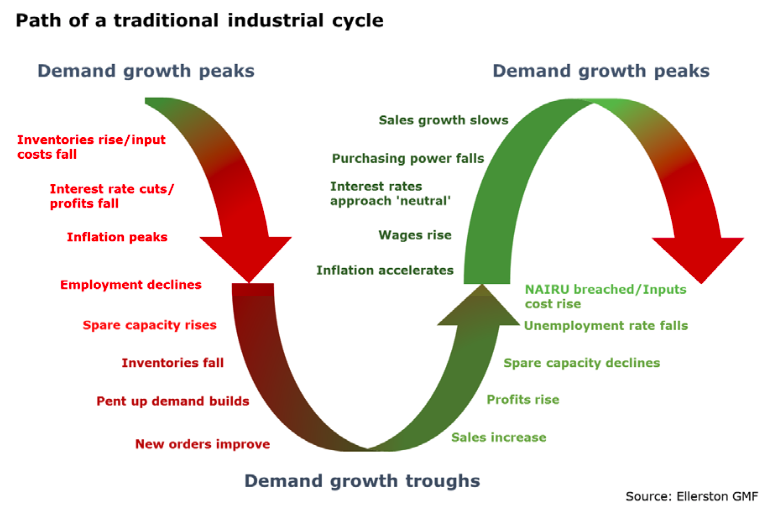

Why the Fed? Because of the business cycle.

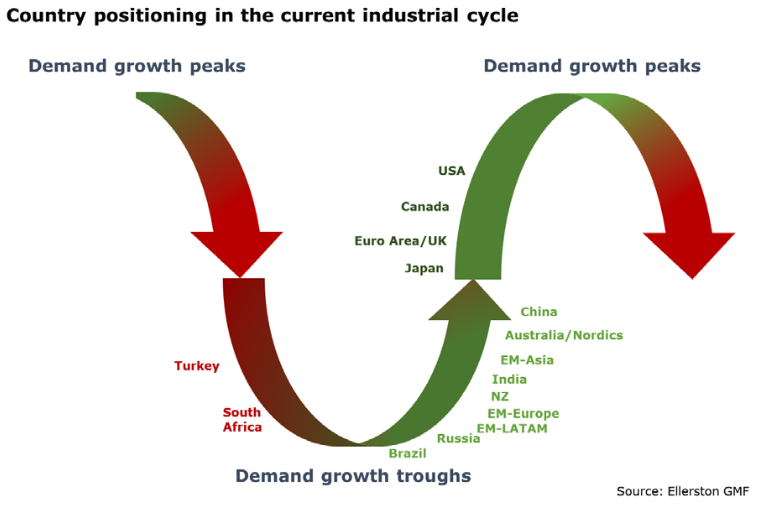

We see the US as well advanced in the business cycle.

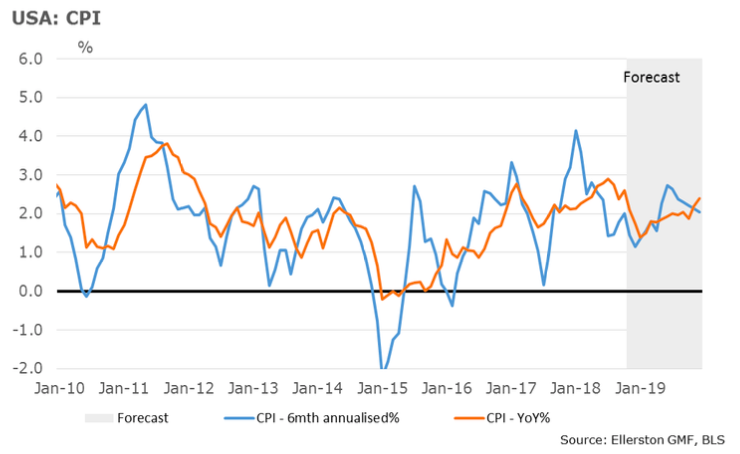

Thus our view of a very real risk the Fed is behind the curve (2) and inflation will rise. Except the fall in oil prices this month, from $75 to $50, is a very timely offset to the business cycle pressures and has significantly lowered our inflation forecast for next year.

Indeed the combination of a tightening in financial conditions in the last two months, and a lower inflation forecast, has necessitated a revision in our Fed rate outlook. We only expect two hikes next year, rather than the four we expected a couple of months ago. But like the Fed, we are data dependent. Well, in our case, FCI dependent.

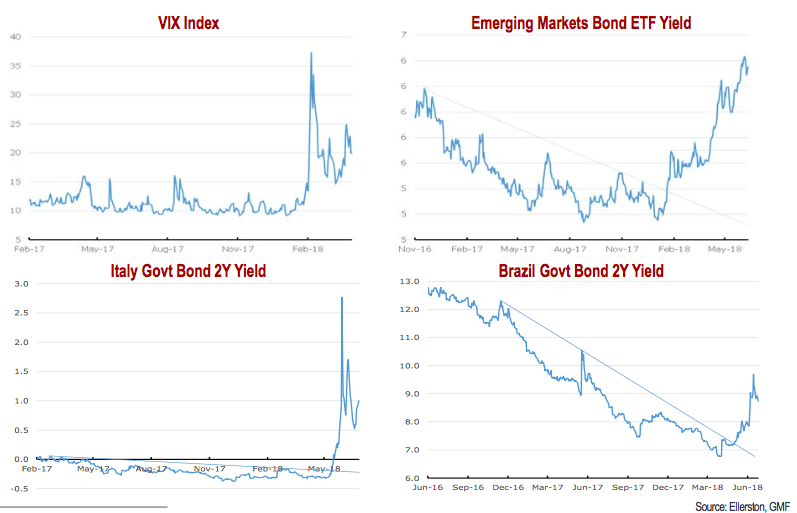

So what happens next? It has been a very volatile year for asset markets. Is this due to the Fed and the business cycle? Actually, not especially. What we are seeing this year is volatility driven by the withdrawal from an addiction. And that is the addiction of all asset markets to a decade of zero interest rates and quantitative easing. Let’s call it a series of “cold turkey” shakes. Punctuated by geopolitical posturing and instability in foreign relations.

Basically this is carry strategies busting. By that, I mean strategies investors have pursued, and even levered up into, on the presumption that low volatility and low interest rates were here to stay. And after being so rewarding for a decade, there is still a lot of money invested on this premise. Meaning, there is still a lot of uncomfortable unwinds to come.

We have spent the year focussed on the Fed normalisation. Meaning we have been following the business cycle model in the chart above, and been focussed on pressures building in the US economy that would need to be addressed through Fed hikes and higher bond yields. But looking for higher bond yields, being “short” bonds, is like being short volatility. Every time a calamity happens, bond yields fall, or “rally” in price. And so we have had to navigate the above events. Most of the time we did this quite well, a couple less well. But all the volatility shocks in the first 9 months of the year subsided relatively quickly. And so the focus on the business cycle and the job ahead of the Fed remained our main focus.

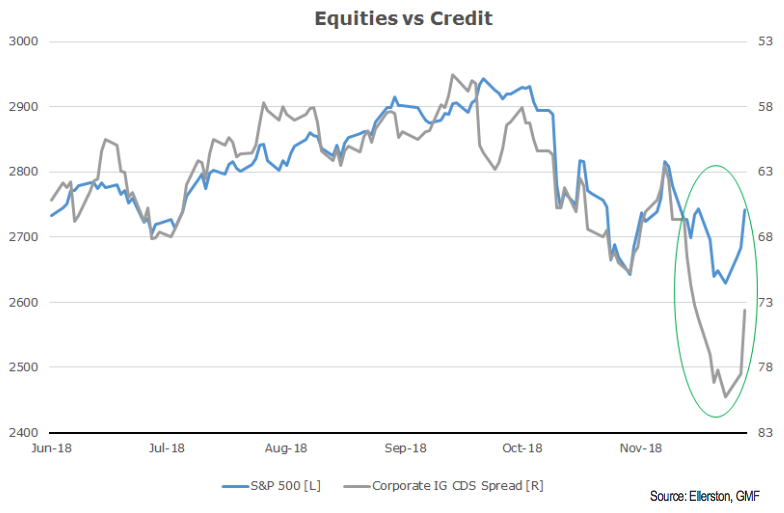

Now it is a little different. Now there is activity in the Ardennes. Corporate credit spreads are starting to perform poorly. And underperform other risk assets.

Corporate spreads carry an outsized weight in our FCI (see last month’s thought piece here). Hence the growth downgrade.

So far authorities see this as a minor diversion. Powell attempted a re-assuring speech last month where he considered where the next problem, or “attack”, might come from. In short, he concluded the likelihood of a financial crisis in coming years was relatively low. He did note corporate debt levels were high, but not alarming.(3)

And RBA Deputy Governor Debelle also gave an interesting speech in early December (4), looking at lessons learned from the last crisis and what might be next. I asked him whether he thought US credit might be the next problem, and in short his answer was no. But his answer, like Powell’s conclusion, was focussed on “financial stability”. That a “problem” in US credit won’t pose systemic risk to the economy via financial institutions (a la GFC).

This is because the holders of credit are not (typically) leveraged. Very true.

So that should make you very comfortable as an investor.

Very untrue.

Saying a “problem” in credit won’t pose systemic risk is very different to saying a “problem” in credit won’t pose recession risk. And a recession is a big problem for investors.

As we see it, the authorities have been building a Maginot line for the last war.

And when they look forward and assess the vulnerabilities of their Maginot line, they conclude it is pretty safe.

Our conclusion is different.

After 10 years of zero interest rates and central banks purchasing 18 trillion in government bonds (Quantitative Easing or QE), debt in the government sector and corporate sector has exploded.

There will be consequences.

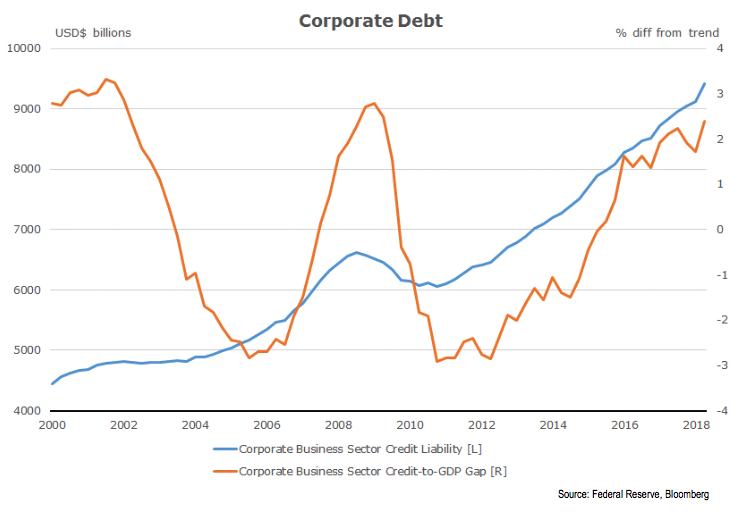

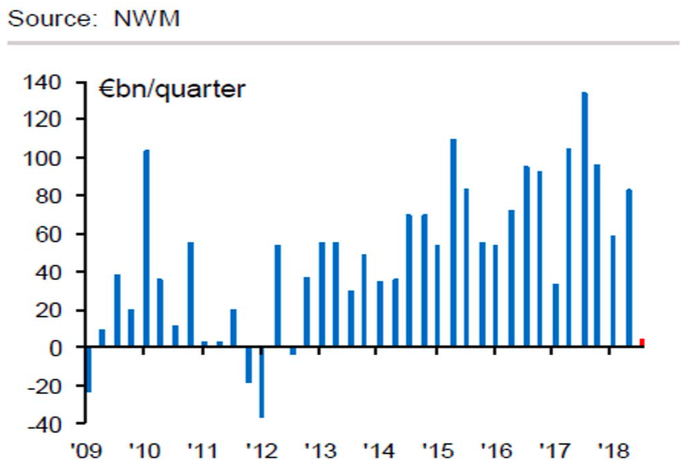

In our June newsletter (5), we investigated the consequence of QE. The bottom line was money crowding into every nook and cranny of the world where they can collect just a little bit more yield. A 300% increase in money invested in emerging market corporate bonds, a 200% increase in emerging market sovereign bonds, and a 100% increase in US corporate bonds.

We think this flow will reverse. But when? And does it have to bust, or merely reprice? Powell argued corporate credit is at normal levels for this stage of the cycle.

That is perfectly true. The amount of debt corporates are running is not abnormal after a long expansion.

But what about the price of credit? What extra yield do investors receive to compensate for default risk? Will they continue to be attracted to this asset class if the risk of a recession is rising? Or if there are better returns elsewhere?

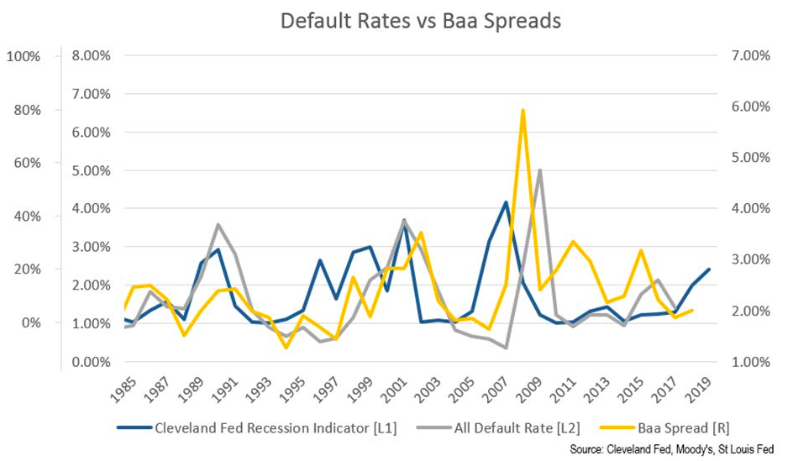

Typically when investors purchase corporate bonds they consider what is the risk of default, and is the extra yield, the spread they are receiving, compensating them for the risk of default. Necessarily in considering this value proposition, they need to determine where they are in the business cycle. Obviously the risk of default is much higher in a recession, or even a slowdown. And so depending on that opinion, they will either seek a normal spread to cover a normal default period, or a wider spread to cover recession-like defaults. So what are they currently getting? (6)

They are getting spreads consistent with a strong mid-cycle economy. Why so little? Quantitative Easing (QE).

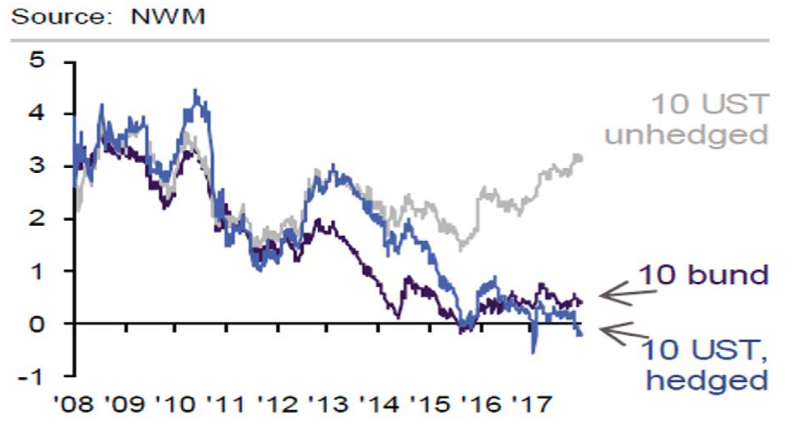

QE has lowered yields on all investment returns. So a low historical return on US corporate bonds has still been relatively attractive, compared to European or Japanese bonds, or the cash rate.

Indeed, Europeans have been buying foreign fixed income, predominantly US corporate bonds and treasuries, at an average rate of Euro 80 billion a quarter for the last three years. Last quarter they stopped.

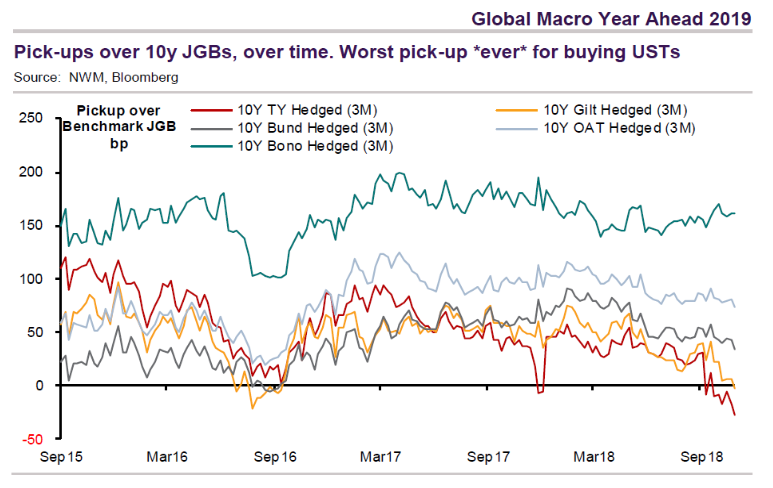

Why? Because with the Fed hiking, their FX hedged returns (7) have turned negative on US treasuries (and barely positive on US investment grade credit relative to risk free German bonds).

And it’s the same for the Japanese. (Their return on FX hedged treasuries is the red line. Bono is Spanish bond in case you were wondering).

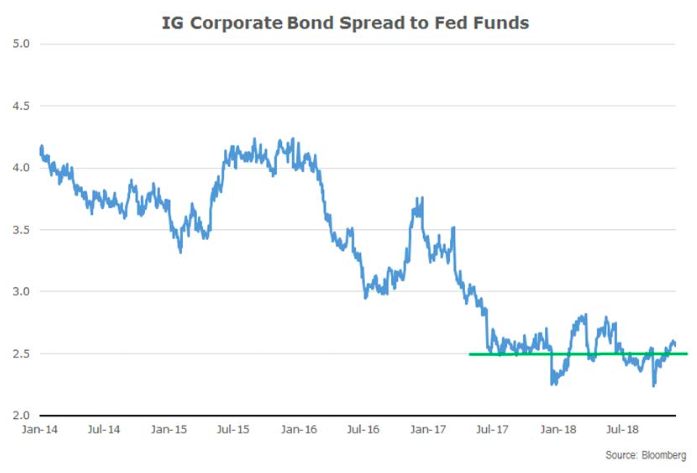

It also seems as money market returns rise, and cash returns as an asset class, there is a minimum return that investors seek in corporate bonds relative to cash. About 250 basis points.

So corporate yields are now rising in lock-step with the Fed.

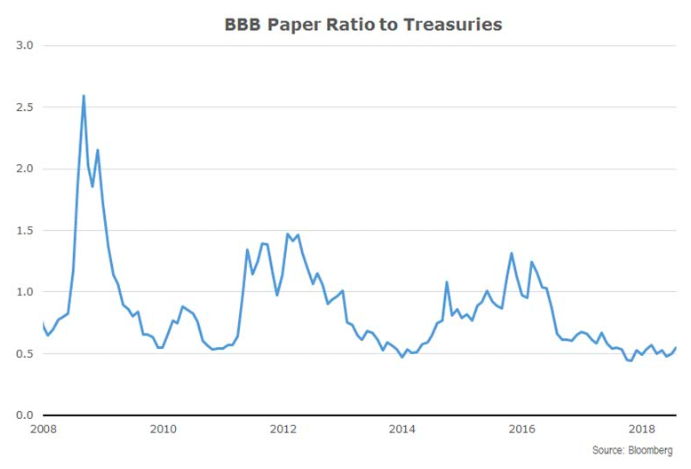

What about pension funds and bond portfolios. They don’t want to hold cash, so that won’t matter to them right? But they don’t have to hold corporate bonds either if the return is not great. Particularly if it is not great relative to holding US treasuries. And right now, the yield pick-up for a pension to invest in a corporate bond rather than a treasury bond is pretty much the lowest in a decade. At a time when one might just want a little more “recession risk” embedded in the corporate bond yield. (8)

So it is pretty clear to us that with the cessation of quantitative easing, the increased risk of recession, and the relatively narrow corporate spreads, this asset class is very vulnerable to a repricing. And sadly, our FCI is very sensitive to corporate spreads. Meaning a repricing in corporate spreads will dramatically increase the slowdown in the US, to the point that a recession becomes probable, rather than possible, and asset markets will need to price accordingly.

The price action in November, with the underperformance of credit, suggests we might be at the start of this story unfolding. Powell, like the French high command, appears to see credit as a diversion. We, on the other hand, are scrambling our portfolio to be prepared for a credit event. We are selling, or shorting, credit ETFs in the US, and buying protection through CDX option structures.

However, we can’t be sure now is the time. And if it is not, the Fed is not out of the Ardennes (so to speak). The attack will eventually be more conventional – wage and inflation. Which requires us to position the portfolio entirely differently, namely more Fed hikes and higher bond yields.

That said, and as noted above, the movement in oil and its impact on inflation now affords the Fed some latitude to assess this risk. That could provide a reasonable window of benign conditions, which is currently the Fed’s central case. The glass half full, or goldilocks scenario, if you like. It assumes no consequences from 10 years of quantitative easing. And it assumes the tightest labour market since the late 60’s, and the concomitant rise in wages, will be met by a just in time rise in productivity that will placate inflationary pressures. I could see the market spending a couple of quarters embracing that scenario. Another year is hard to see given unemployment by then will be testing 3%.

So we see the following three scenarios:

Scenario 1: Benign outlook

- Wages matched by productivity gains/Inflation contained

- Fed moves to neutral/modestly restrictive, treasuries 2.8-3.4%

- Business cycle extended, equities positively re-rate

Scenario 2: Inflation rises

- Policy has not been this easy since the 60’s. Inflation accelerates

- Fed cash rate and 10 year yields move to 4-5%

- Recession risk surges, equities crash

Scenario 3: Unwind of credit yield chase

- Global credit markets crash/rerate

- Tightening in financial conditions dramatically slows growth/cause recession

- Equities crash, Fed aborts, rates rally

Today we would put the highest probability on 3. But we will continue to follow the reports coming from the Ardennes (markets), and adjust our probabilities accordingly.

We accept that the credit unwind doesn’t have to happen now (9). But the price action of the last month suggests it could be happening now. So now is the time to be positioned short credit, and review if it doesn’t happen. That is how we are positioned.

The Ellerston Capital Global Macro Fund is an absolute, unconstrained strategy investing in a number of fundamentally derived core themes, optimised via trade expression and portfolio construction across Fixed Income, Foreign Exchange, Equity & Commodities. It focuses on capital preservation while providing low to negative correlation to traditional asset classes. Find out more.

_______________________________________________________________

(1) It has also been suggested that the French plan was to force the Germans to take this route so the war could be fought in Belgium and bring the Belgian and English in.

(2) Behind the curve means the Fed has not hiked to prevent inflation pressures building, and longer maturity bonds will then price a higher risk of inflation. This causes longer dated bonds to rise more than shorter dated bonds, which are anchored by the slower pace of rate hikes, and the curve steepens.

(3) Powell speech (VIEW LINK)

(4) Debelle speech (VIEW LINK)

(5) (VIEW LINK)

(6) The credit spread yellow line does a reasonable job of pricing actual defaults (grey line). And the Fed’s recession indicator does a reasonable job of leading defaults. As one would expect. With recession models moving higher, investors should start to demand wider credit spread for “insurance”.

(7) If you want to buy a 10 year bond in Germany you receive a 0.25% return. In the US you receive 2.8%. Sounds great, except is the USD weakens 5% whilst you hold that USD bond, you lose 5% in value. And so investors protect against currency movement when they buy overseas bonds. To protect for 1 year, back in 2014, it cost zero, because the borrowing and lending rates for 1 year in both countries were roughly the same. Now after Fed hikes it cost over 3% a year, eliminating the positive return on treasuries.

(8) Chart show investment grade credit spread divided by US treasury yield. Currently an investor receives about 50% extra yield. 100% extra would be “normal” for this stage of the cycle.

(9) Although we expect a credit unwind at some point, timing of that unwind has had to necessarily become informed by the price action in the market itself. Which in October and November has been, shall we say, schizophrenic. When equities and credit rally on a dovish Fed or trade truce, we have to acknowledge that scenario 3 may have to wait for another time and the market will spend more time pricing scenario 1. When oil falls or financial conditions tighten we have to downgrade the probability on scenario 2. And so on.

4 topics

1 contributor mentioned

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.