Unravelling the Aussie bank liquidity mystery

Coolabah Capital

A scarcity of Australian government debt meant that the RBA and APRA had to be creative when implementing the post-GFC global banking reforms, known as Basel 3. The solution to the scarcity of government bonds was for the RBA to commit to give banks liquidity against alternative collateral in what became known as the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF).

A large increase in the size of the government debt market, and a massive increase in the amount of cash in the system, means that there are now enough High Quality Liquidity Assets (HQLA) to meet the banking system’s needs. That is, APRA could now eliminate the CLF, if it wanted to do so. Given institutional conservatism, a large cut in the CLF seems more likely than total elimination – but elimination cannot be ruled out.

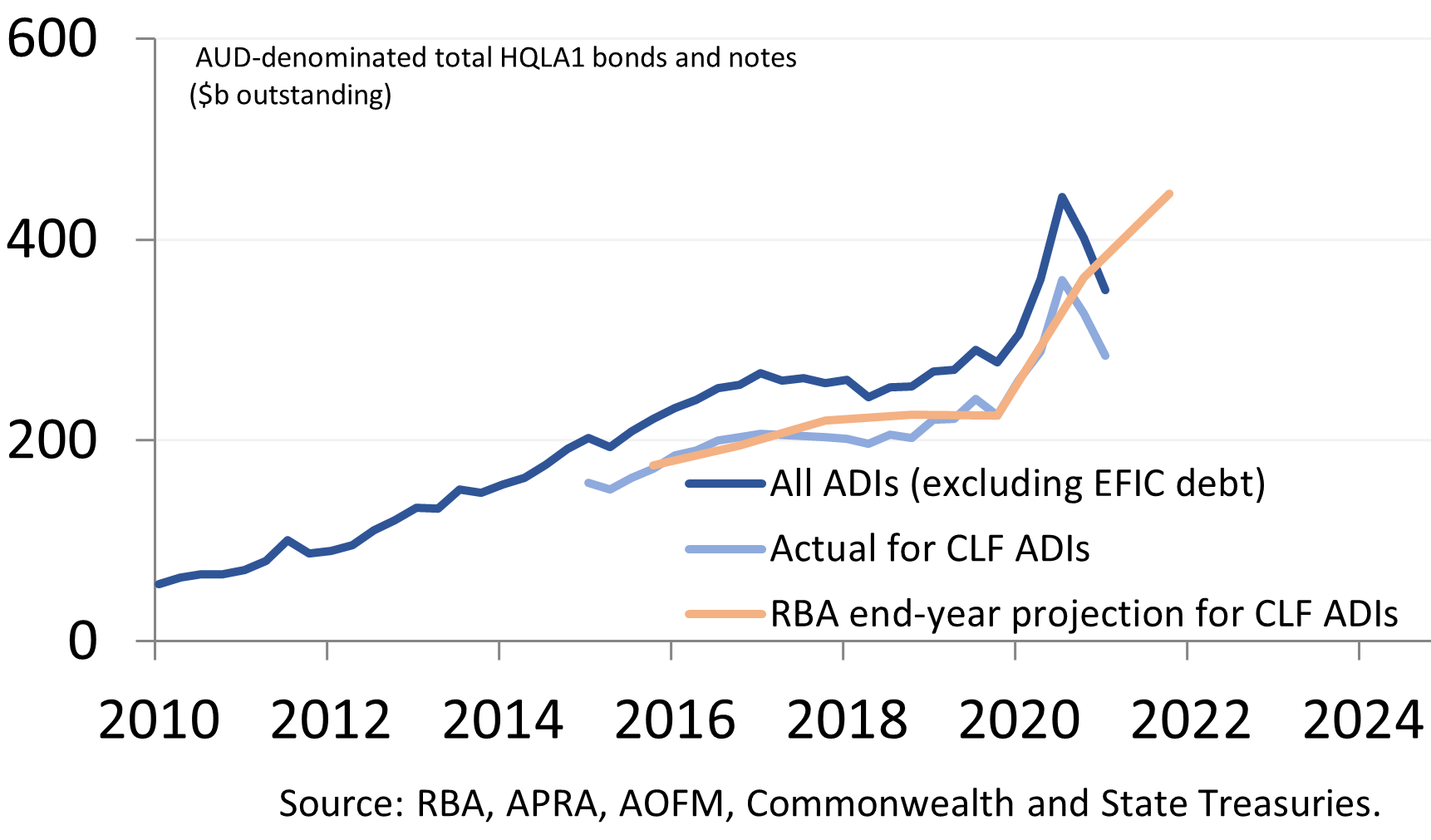

When the CLF was implemented in 2015 there were not enough government bonds to go around. The size of the high-quality government bond market was small, the repo market was immature, and foreign ownership was high. As a result, there was a reasonable fear that the high-quality government bond market might become illiquid if Australian Deposit taking Institutions (ADIs, which are predominately Banks) purchased too many bonds.

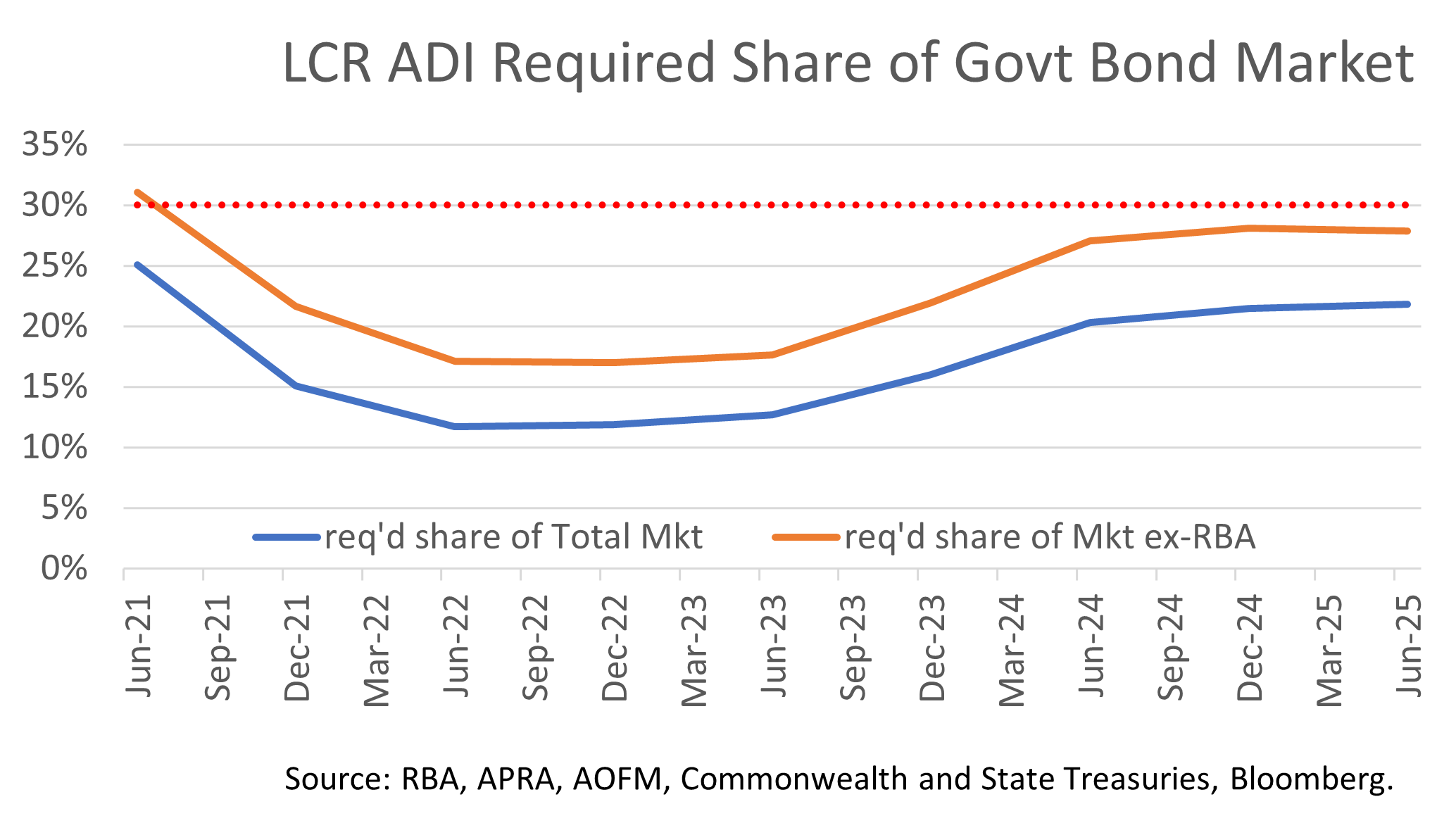

To solve this problem, the RBA decided to cap ADI ownership of high-quality government bonds as share of the market (initially at 25%) and provided ADIs with a CLF to make up the balance. The combination of these two sources of liquidity ensured that ADIs were able to meet their regulatory ratios, and specifically the Basel 3 Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), while at the same time preventing the high-quality government bond market from becoming crowded and illiquid.

Things have changed since 2015.

The high-quality bond market is larger, the repo market has matured, and foreign ownership is lower. More importantly, the RBA's QE program has created a large new stock of liquid assets: Exchange Settlement (ES) Balances, which are cash deposits at the RBA.

ES Balances are now a large source of HQLA and they ought to be counted.

APRA and the RBA quickly responded to the developments in the government bond market. They first boosted the share of the high-quality government bond market that ADIs were permitted to hold (to 30%, reflecting a larger market, better repo and lower foreign ownership). Next, as the bond market grew, they accelerated the reduction of the CLF over 2020 and 2021. A larger market means more bonds; so, the free float goes up in dollar terms even if banks hold a larger share of the market.

However, they have not made an adjustment for the growth of ES Balances, which seems odd given that they are ‘the ultimate form of liquidity’ (RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle speaking to the House Economics Committee on 6 August).

Conservatism seems to be the explanation. An RBA Bulletin article explains that “APRA assumed CLF bank’s surplus ESA balances would be around the (significantly lower) levels of previous years when calculating the size of the CLF for 2021”.

There is a strong case for changing this assumption for 2022.

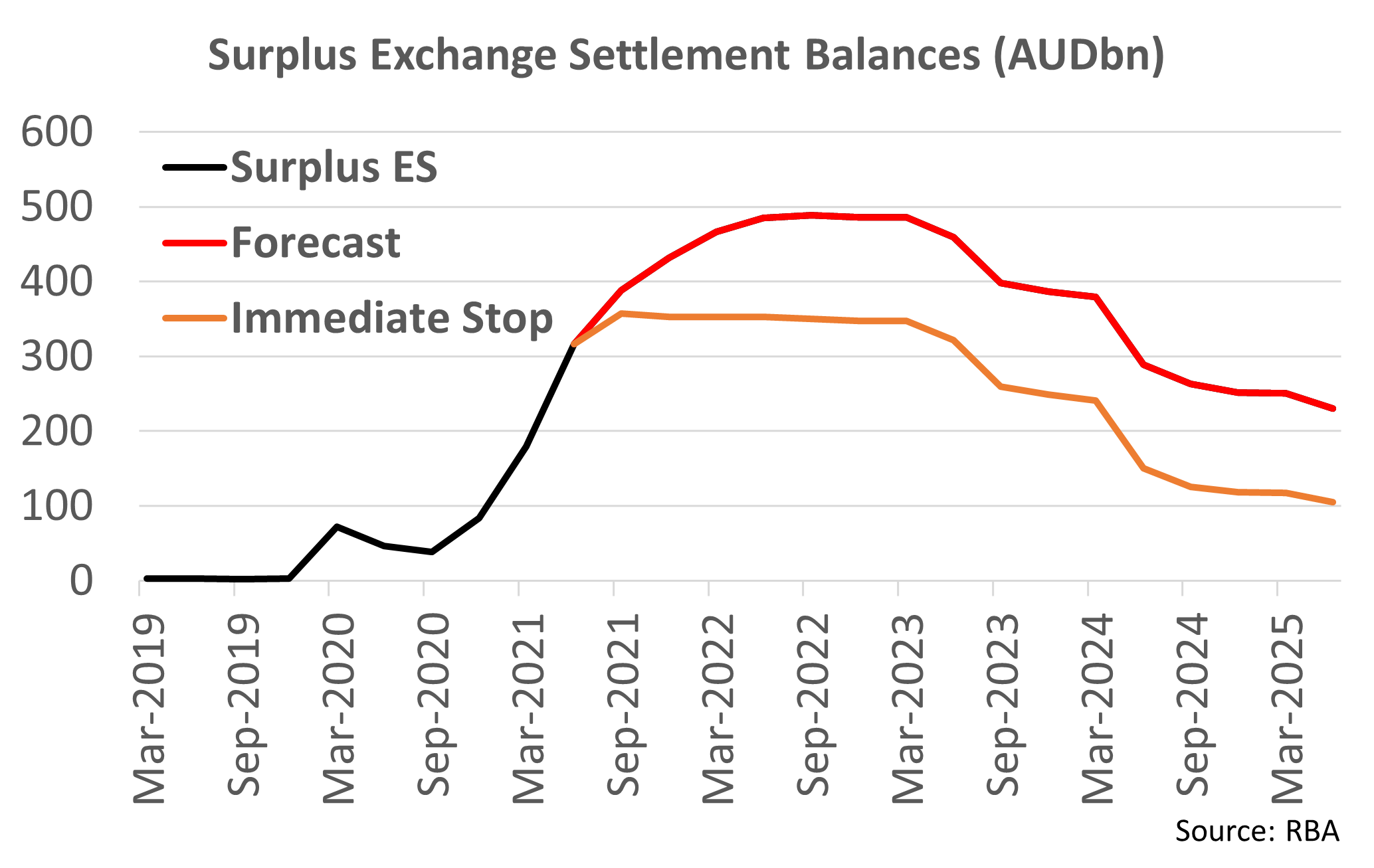

ES Balances are high, rising, and will not return to their pre-pandemic level for a long time. If the RBA stopped QE today, Surplus ES balances would remain around $350bn until H2’23; and still be over $100bn for most of 2025. Assuming QE continues in line with market expectations, Surplus ES balances will rise to around $500bn in 2022, before declining to still be over $200bn in 2025. Given the RBA’s large portfolio of bonds that mature after 2030, Surplus ES balances are unlikely to return to prior levels until the end of the decade.

Given that ES Balances will remain elevated for some time, APRA and the RBA ought to include them in their calculation of available HQLA when calculating the size of the CLF.

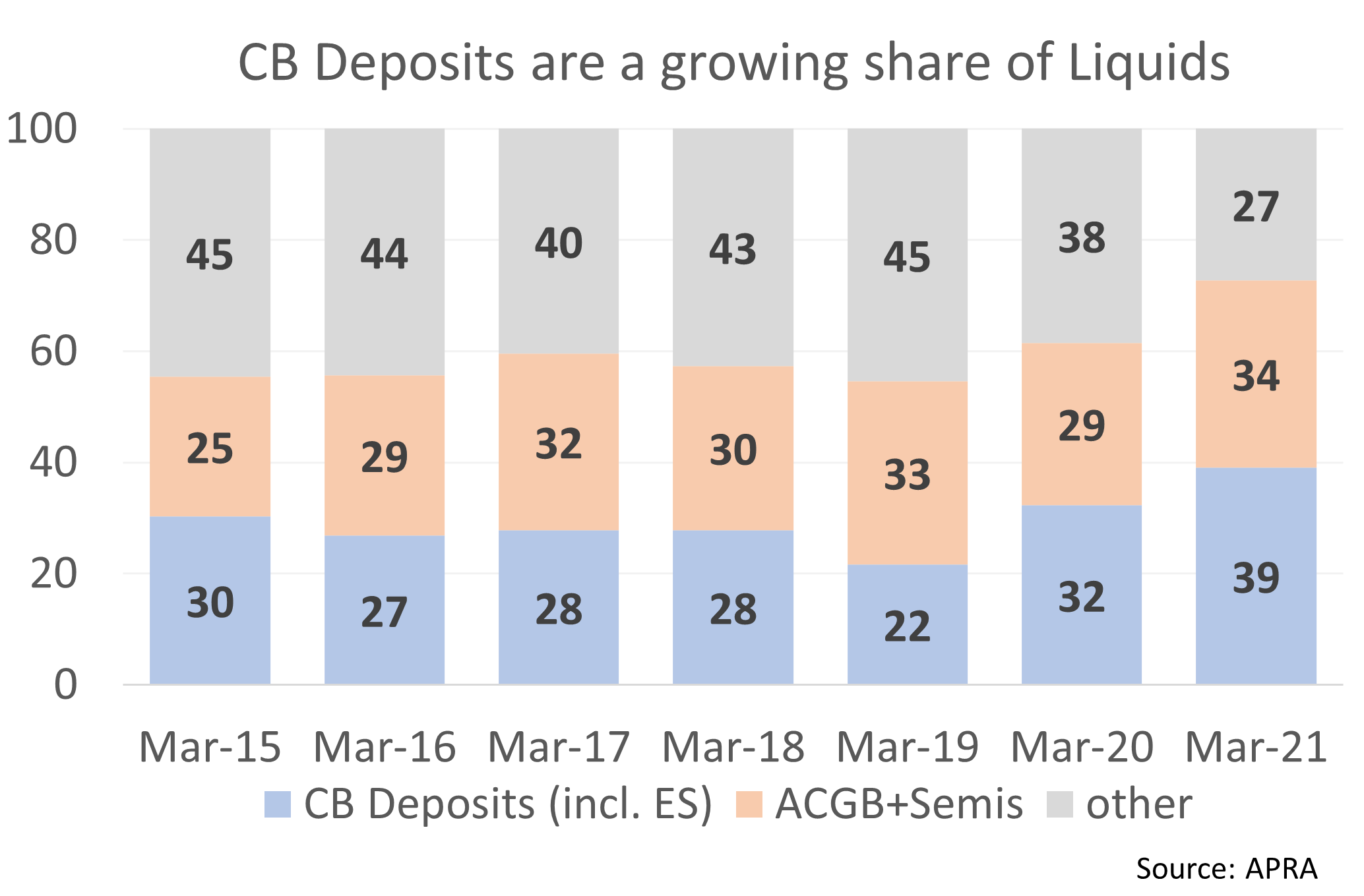

Notwithstanding that ES Balances have been assumed away by APRA (for 2021), they are currently a major component of ADI liquidity portfolios. Larger ADIs, which must comply with Basel 3 LCR regulations, have increased their holdings of Central Bank Deposits (of which ES Balances at the RBA are the largest component) by over $150bn since 2019. Ongoing QE means that ES Balances are likely to rise further over the next few years, so Central Bank Deposits are likely to become an increasingly large share of Australian ADIs liquid assets portfolios.

QE makes this work – because it boosts the quantity of liquid assets that banks can hold. This happens because when the RBA buys bonds it transforms high-quality government bonds, where liquidity considerations mean that ADIs must not own too much, into ES Balances, where concentration isn’t a concern.

There’s no reason that ADIs shouldn’t hold 90% of the ES Balances in their HQLA pools. Prior to 2020, Surplus ES Balances were seldom larger than $3bn. So, even if ADIs held 90% of Surplus ES balances there would be more than enough cash in the system (this remains true for most of this decade, despite declining Surplus ES Balances).

Given that ES Balances are likely to be high for a long time, and that there’s no reason ADIs should not hold a very large proportion of them, it follows that the RBA and APRA ought to include ES Balances in their estimates of the available stock of HQLA.

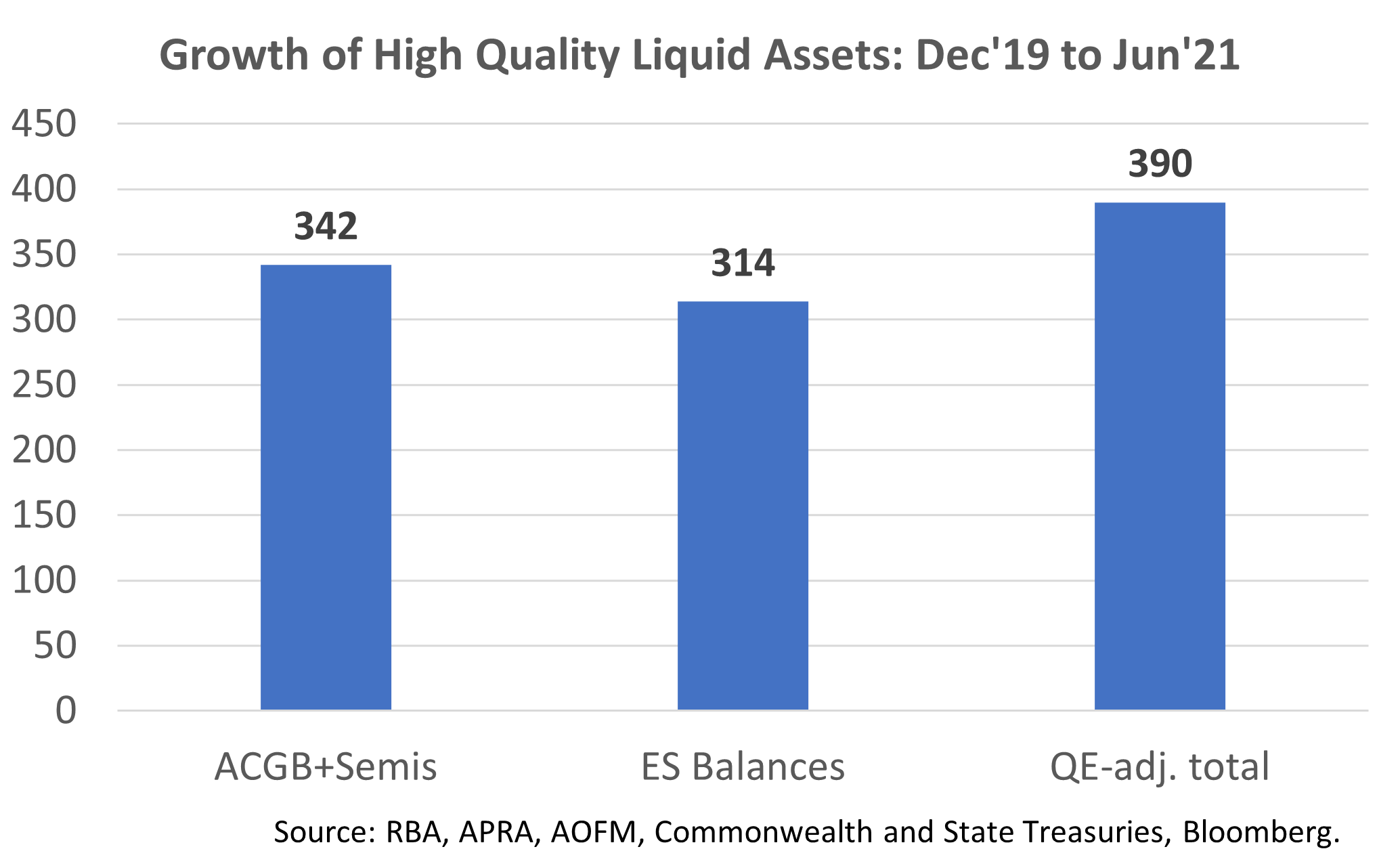

There is, however, one adjustment that must be made if they do so. RBA holdings of bonds must be subtracted from the size of the bond market when calculating the available pool of government bonds. Otherwise, bonds the RBA owns would be counted twice: once as part of the bond market; and a second time when ES Balances are added. This is the QE-adjustment that was made in chart 1.

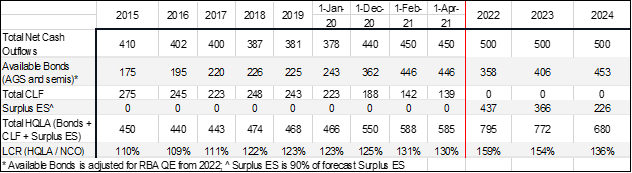

According to APRA data, LCR ADIs currently hold around $284bn of high-quality bonds (Commonwealth and State Government bonds). This is down from a peak of $360bn in 2020.

If ADI holdings of government bonds remain stable at $284bn, the large increase in ES Balances means that there’s more than enough HQLA to keep system-wide LCR above 125% over the next few years.

Assuming $284bn of bonds, LCR ADIs would need to hold only 70% of the $485bn stock of ES Balances to be self-sufficient in 2022. This allows for a $50bn increase in Net Cash Outflows (NCOs), to $500bn (NCOs are to the amount of cash that might leave a bank in a 30-day crisis).

As ES balances decline, ADIs will need to buy more bonds – but a growing market means that isn’t a problem. Assuming ADIs held no more than 90% of outstanding ES Balances, their required share of government bonds (net of RBA bond holdings) would not rise above the 30% cap the RBA has set for LCR ADI ownership of bonds (ACGBs and Semis).

Of course, LCR ADIs might not like to hold large amounts of zero-interest ES Balances. But that’s orthogonal to the regulatory question. The relevant question is capacity.

APRA's regulatory standard APS 210 requires ADIs to make every reasonable effort to manage their own liquidity risk through their own balance sheet before applying for a CLF for LCR purposes. The increase in the availability of HQLA, due to QE-fueled growth of ES Balances, means there are enough high-quality liquid assets for LCR ADIs to be entirely self-sufficient in the management of their liquidity risk.

The ANZ Bank’s Pillar 3 report shows that it is a practical option. Over the past two years, ANZ has reduced their CLF by almost $40bn, to $10.7bn. In doing so, they have lowered the share of the CLF in their stock of liquid assets from 25% to less than 5%.

If ANZ can do it, so can other banks. It follows that APRA and the RBA could eliminate the CLF starting in 2022 – if they wanted to.

The main reason for conservatism on ES Balances is uncertainty about their future level. However, with the COVID/Delta outbreak slowing the economy, it seems more likely that both Bond Issuance and QE will be larger than has been assumed in these calculations. Both developments favor a smaller CLF.

On the other hand, elimination of the CLF would be entirely consistent with APRA's repeated guidance that "it would be reasonable to expect that if government securities outstanding continue to increase beyond 2021, the CLF may no longer be required in the foreseeable future".

Government securities have continued to increase, and will continue do so for many years.

So the question is, do they want to close the CLF?

A large cut seems more likely than elimination. But ANZ shows elimination is plausible.

3 topics

4 stocks mentioned

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...