China – the tariff threat, structural challenges and implications for Australia

Despite plenty of concern around the property downturn, structural problems and now US tariffs, Chinese economic growth has so far been okay.

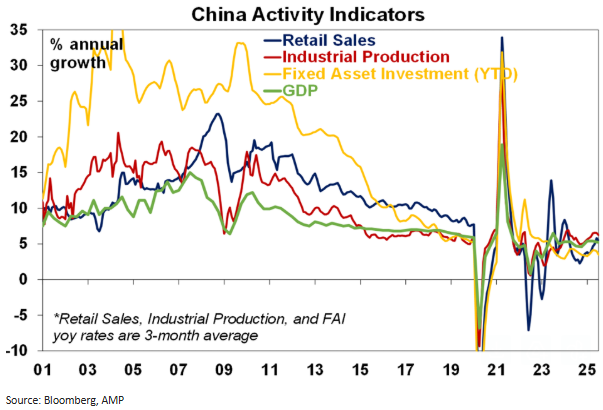

Compared to the roaring 2000s there is no doubt that Chinese growth has slowed. Whereas it used to be averaging around 10% pa, it’s now around 5%. But such a slowdown is inevitable as a country develops and the easy gains of switching from simple farming to industry are seen. And 5% is still solid by global standards.

Looking at recent indicators:

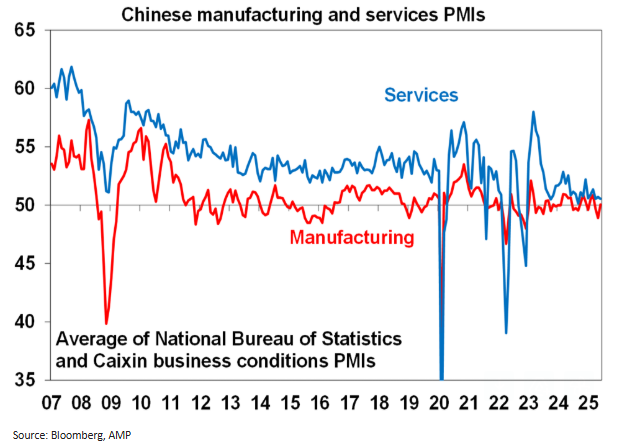

- Chinese business conditions PMIs are bouncing around subdued levels.

- But despite this growth, rates for key indicators have been tracing out a flat to slightly rising trend, credit growth has picked up slightly and GDP growth is relatively stable around 5% yoy.

- While slumping property investment remains a drag and home price falls are accelerating again, property sales may be stabilising.

- Despite the US tariff threat Chinese export growth has been boosted by exports to the rest of the world excluding the US.

- Finally, soft demand growth and excess capacity is evident in roughly flat imports, falling producer prices and subdued core CPI inflation.

Six key structural challenges

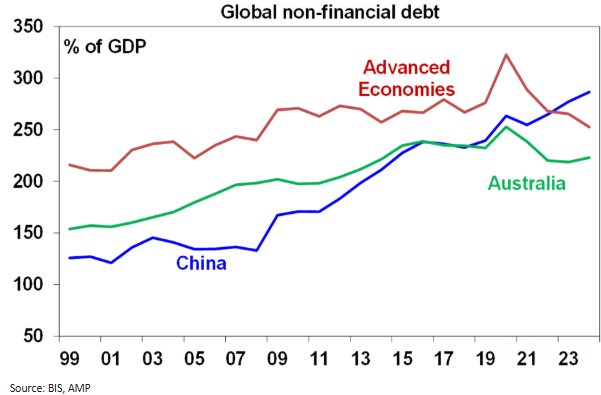

1. Excessive savings - China has a very high total saving rate of around 45% of GDP, compared to around 25% in Australia. This reflects high household saving as a lack of social welfare makes households wary of spending. The trouble is that the savings have to be recycled (usually via debt) into demand or else high unemployment can result. China did this for many years through corporate borrowing for investment focussed on driving exports and then into property which has resulted in a rapid rise in debt levels. China’s non-financial debt to GDP ratio is now above the advanced economy average and Australia.

China’s debt problem is very different to other countries though as it borrows from itself.

In essence, China saves too much and spends too little with the outcome being a current account surplus and a flow of capital out to the rest of the world.

The US does the opposite with a total saving rate of just 18% meaning that it saves too little mainly due to massive budget deficits and spends too much leaving it dependent on foreign capital. This is the real reason the US has a trade deficit - not the rest of the world “ripping the US off” as Trump claims. The US needs to save more and spend less; China needs to spend more and save less.

2. Problems in export related investment – recycling excess savings into export related investment has soured as rising levels of fresh capital and debt are leading to a diminishing payoff in terms of GDP, geopolitical tensions and trade restrictions. China has borne the bulk of Trump’s ire on trade. But Europe has also raised trade restrictions on China.

3. Problems in property-related investment - using property to recycle high savings has also soured. This was viable when urbanisation was rapid, but it’s led to an oversupply of property and falling prices.

4. Poor demographics – China’s population and workforce are now falling at about 0.1% to 0.2% pa and its population is rapidly aging. This weighs on property demand and potential economic growth.

5. More government intervention – the easy gains of industrialisation have been seen leading many to fear that China is at high risk of falling into the “middle income trap”. This is partly because of increasing state intervention in the economy acting as a disincentive to entrepreneurs.

6. There is a fiscal imbalance between the central and local governments – with the former having most of the revenue and the latter doing much of the spending resulting in local government debt problems.

Reflecting these challenges, estimates of its potential real GDP growth have fallen from around 10% in 2006-10 to 5% now and 3% for the next decade.

Policy moves, Chinese brands and tariffs

Rising US/China geopolitical tensions are a big source of uncertainty. But they may never come to anything and even if they do, trying to predict them as with most geopolitical events will be hard. Putting geopolitical tensions aside, here are some key observations regarding China’s growth outlook.

- Policy stimulus will support growth but will likely remain more incremental and reactive than big and proactive. A run of soft economic data last year helped spur stimulus announcements last September and October with the People’s Bank of China announcing significant monetary easing and the Politburo committing to increased counter-cyclical policies on top of a program designed to encourage consumers to trade in old for new goods. This helped stabilise economic growth & credit growth. However, stimulus has remained relatively measured. This possibly reflects economic growth remaining around the 5% target, the US tariff truce and an ability to redirect exports to other countries.

- The renewed property slowdown may prompt a new round of property support, but it’s likely to be modest, and just enough to avert a major crisis rather than start a new boom (to avoid the problems of the past).

- A renewed trade war between the US and China - if the current truce (set to expire on 12 August) and trade talks fail to yield results - is the main risk which could prompt more aggressive policy stimulus in China.

- Overall, we expect policy stimulus to be just enough to avert a major crisis and designed to keep growth around the 5% target.

On the structural front, there have been some positive developments:

- There have been reports recently that China is planning “baby bonuses” or cash handouts to families for each child until they turn three of around $A760 a year to help boost the birth rate. However, the experience of many other countries has found that reversing falling fertility will be an uphill battle as the desire to have children falls with increasing prosperity and the costs of maintaining that prosperity.

- Since 2023 China has sought to rehabilitate the influence of tech entrepreneurs like Jack Ma. And the rising success of Chinese brands – from BYD to Labubu - suggest China is not lacking entrepreneurial spirit.

- There has recently been talks of measures to address industrial excess capacity – although we have been hearing of that for years.

Overall, the longer-term outlook for China is better than the cynics portray it, but key challengers are likely to remain.

In particular, saving is likely to remain too high and consumer spending too low (just like the opposite will remain in the US with Trump keeping the budget deficit high and using tariffs to deal with the symptoms but not the cause of its trade imbalance); the trend towards increasing state intervention is likely to remain for a while yet; the revenue/spending mismatch of local governments will remain; and it will be very hard to reverse the deteriorating demographics.

So, a longer-term trend towards slower growth in China will likely remain place. But a cyclical collapse in growth looks unlikely.

The Chinese share market

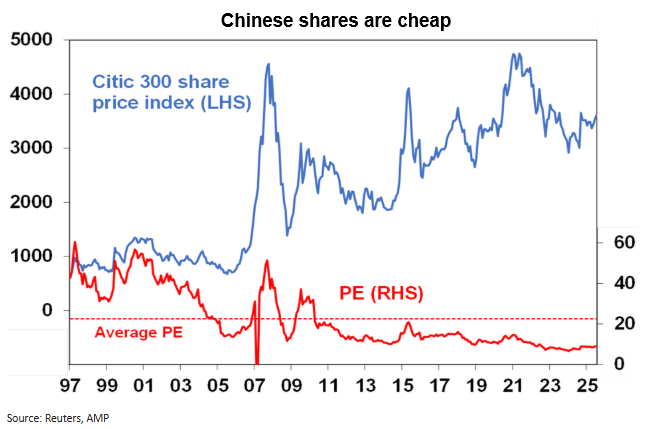

Chinese shares spiked around 30% from their mid-September low into early October on the back of policy stimulus announcements at the time but have since tracked sideways with fiscal stimulus being less than hoped for and tariff uncertainty. They are still cheap trading on a forward PE of 13 times, suggesting room for upside if growth remains okay and assuming there is no new tit-for-tat tariff escalation with the US (which is a big risk).

Implications for Australia

Over the last five years, the Australian economy has been relatively resilient compared to its past correlation to China reflecting a combination of: solid bulk commodity prices; strong population growth; and a muted mining investment cycle.

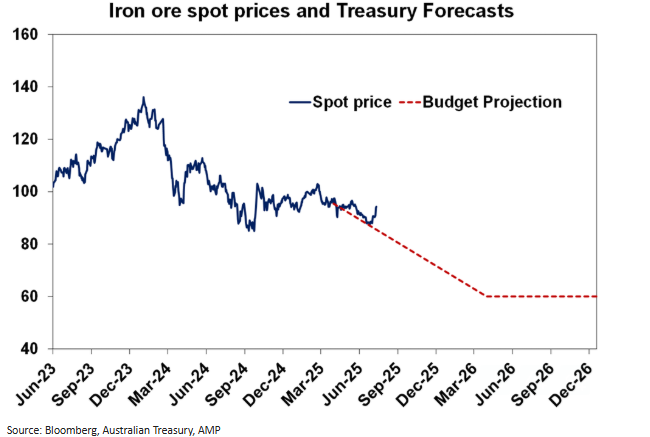

So, another swing up or down in the Chinese economy may not have a big impact on the Australian economy. Our assessment though is that China will do just enough to keep its economy growing at an okay rate which in turn will support demand for Australian commodity exports. And this will likely help keep the iron ore price tracking above the Federal Government’s budget assumptions.

Although, the boost to the budget (via stronger mining profits) won’t be as strong as it has been over the last two financial years.

4 topics