Fed data dependence means less dovish rates pricing now to contain the risk premium in bonds

As widely anticipated by the market, the Fed has cut rates by 25bps at its mid-September meeting to the 4.0-4.25% range. The decision was almost unanimous except for incoming Governor Miran who preferred a 50bps cut. Forward guidance was dovish, suggesting that further rate cuts are possible if the labour market continues to weaken. Interestingly, median rate projections (the “dot plots”) were cut largely due to the inclusion of Miran’s views. However, activity growth forecasts were revised upwards, while inflation forecasts were maintained at elevated levels.

Chair Powell’s press conference was somewhat hawkish in our view. Powell focused on inflation risks, noting that goods inflation has contributed significantly to recent outcomes, and that there remains a danger of persistence. While Powell tempered his assessment of inflation risks with slowing jobs growth, he also emphasised that the recent softening in jobs growth reflects supply-side factors, such as lower immigration. Interestingly, Powell also suggested that the Fed had anticipated 911,000 worth of downward revisions to payrolls, even though they surprised the market in August.

As for rates, Powell characterised the September cut as “risk management”, while downplaying the importance of the latest median projections. In our view, this suggests that he is not buying into a deep rate cutting cycle just yet, but rather a path that is highly data dependent.

In response to the Fed meeting and Powell’s comments, bond yields are up across the curve, with the yield curve modestly steeper. This makes intuitive sense to us, because too many rate cuts had been priced into the curve ahead of time, despite the absence of a recession. Naturally, Powell’s comments suggest that we should temper our rate cut expectations. We also think that the Fed’s data dependent path is much more credible than delivery of the “dot plots”. Yes, it means that bond yields rise because of a lower probability of deep rate cuts. However, the Fed sticking closely to credible policy rules also limits interest rate uncertainty, and therefore the scope for the risk premium in bond yields to increase.

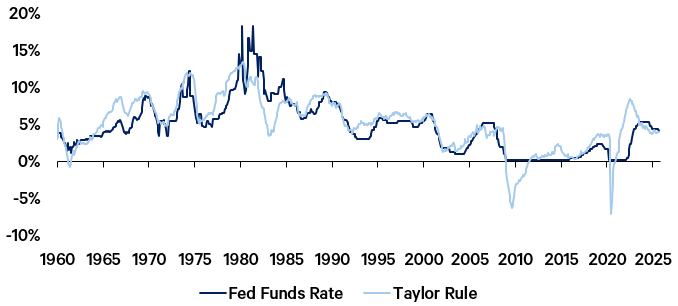

Our preferred Fed “Taylor rule” is based on three factors:

1. A long-term neutral rate estimate based on the sum of 10-year annualized consumer price index (CPI) inflation and 10-year annualised growth in aggregate hours worked;

2. A real-time output gap measure based on industrial capacity utilisation, employment, job openings and labour force data;

3. The deviation of recent CPI inflation from economist long-term expectations.

We apply 50-50 weights to terms (2) and (3) and add this (combined) cyclical variable to our long-term neutral rate estimate. Importantly, we do not overfit the data to explain the history of the Fed funds rate. Nonetheless, because the “Taylor rule” is fundamentally well grounded, it is very highly correlated with the Fed funds rate over time. At present, the “Taylor rule” suggests that rates should be around 3.9%, not too far away from where the actual rate currently sits.

Figure 1: Fed funds rate and "Taylor rule"

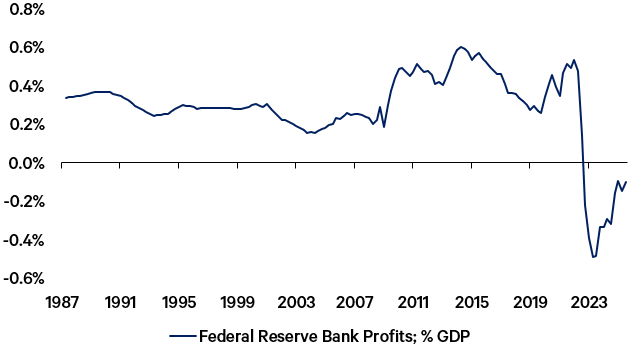

It is also worth noting that the Fed is currently losing on its bond portfolio’s net interest margin, to the tune of -0.1% of gross domestic product (GDP). Fed profits (losses) imply private sector losses (profits), as we live in a zero-sum world. Fed losses notionally add to the fiscal deficit and therefore inject cash into the system. With this in mind, we could say that the Fed funds rate is up to 0.1% lower than the headlines suggest, in which case the current Fed funds rate sits extremely close to where it needs to be. The negligible tracking error of the Fed funds rate to a credible policy rule helps to limit how much rates uncertainty is embedded in market pricing, and therefore limiting how high long-term bond yields can lift relative to long-term neutral rate estimates.

Figure 2: Fed net interest income

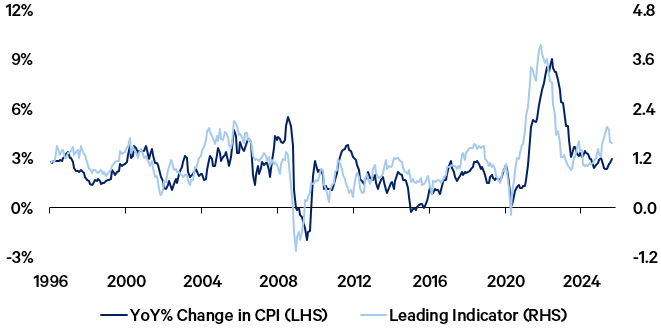

Of course, the fundamentals driving the policy rule can shift. Leading indicators suggest that job openings are likely to weaken further, consistent with a loosening of capacity in the economy and lower rates. On the other hand, leading indicators also point to upside risk to inflation, which drives the calculus the other way. We think that the net balance still favours fewer rate cuts than the market is pricing in. As such, we are biased towards being short duration in our debt portfolio.

Figure 3: US inflation and leading indicator

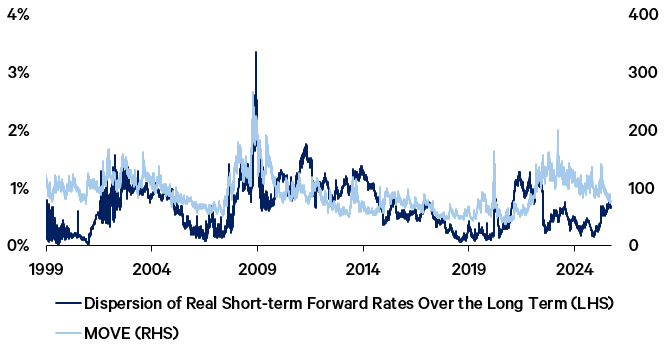

Figure 4: Market-based measures of US rates uncertainty

As for the shape of the yield curve, if the Fed can continue to run a tight tracking error, the advance in its credibility stocks could be rewarded in the form of a lower term premium and a flatter curve. However, if the tracking error starts to blow out, say because the Fed cuts rates against the grain of improving growth and rising inflation, the term premium could rise, resulting in a steepening of the yield curve. In recent weeks, we note that market-based measures of interest rate uncertainty have been tightening, partly because investors are anticipating the appointment of a credible Fed Chair like Governor Waller, and partly because the Fed is currently operating in a credible data-dependent way. We do anticipate more volatility in the data to come, even though growth and inflation considerations are currently offsetting each other. As such, we believe there is a stronger reward-to-risk profile in taking on a duration view rather than a curve-shape view.

5 topics

1 stock mentioned