Is the RBA forward-looking like the ECB and the Fed?

Forecasting is a necessary evil for central banks because policy-makers should be forward-looking when setting interest rates given it can take 1-2 years for rates to affect inflation.

The downside to relying on forecasts is that they are often wrong, which is why central banks also pay attention to both nowcasts – which are just economic forecasts of the current quarter – and recent history.

CCI recently looked at the forecast performance of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) with respect to unemployment and inflation, which are two key inputs into decisions about interest rates.

This first involved comparing RBA and economist forecasts to judge their performance. It next involved looking at whether the RBA reacts more to recent history, nowcasts and/or forecasts when setting interest rates, relative to the European Central Bank (ECB) and Federal Reserve.

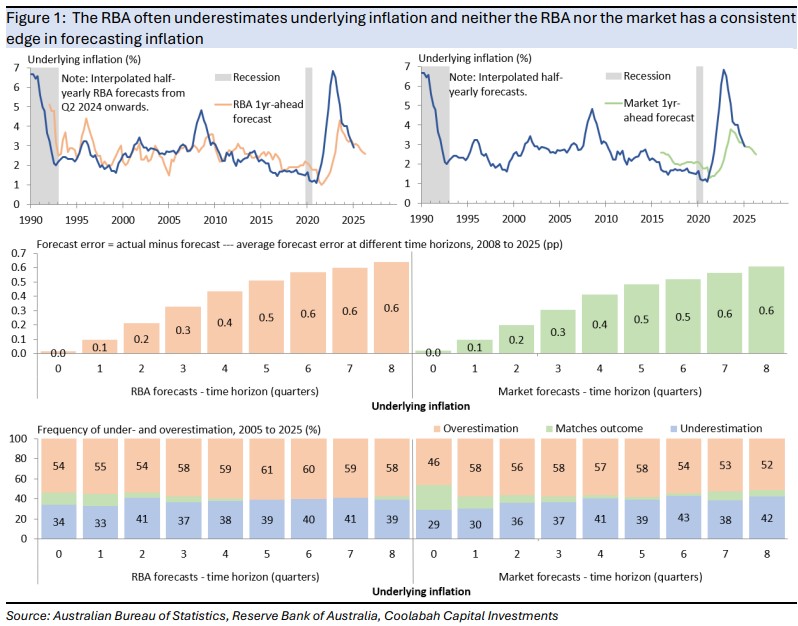

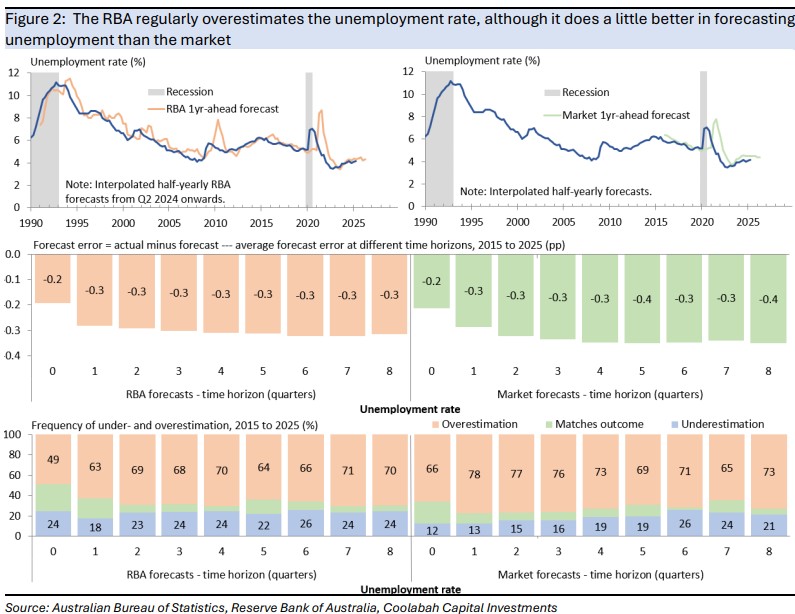

The initial analysis suggested that both the RBA and the market often underestimate underlying inflation over a time horizon of up to two years. At the same time, the RBA and the market have regularly overestimated unemployment.

There is no guarantee that history will repeat itself, but this suggests there is always a chance that inflation turns out higher than expected and a good chance that unemployment is lower than forecast.

In judging who is the better forecaster, a magnifying glass is needed to separate them because the differences in forecast errors are small, but neither the RBA nor the market has a consistent edge in forecasting underlying inflation, although the RBA is generally better at forecasting unemployment.

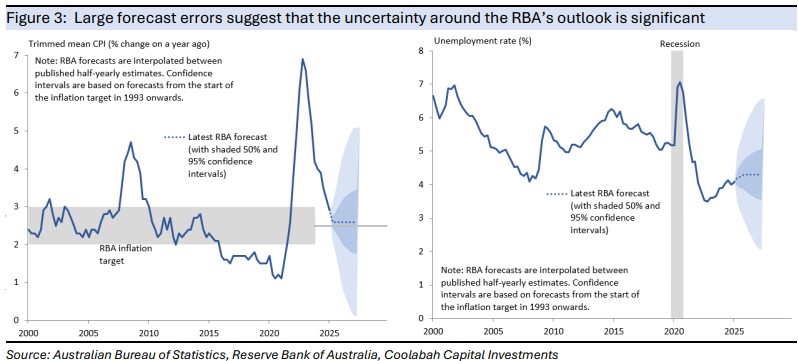

Still the absolute forecast errors are large, which means that uncertainty around the outlook is significant. For example, using forecast errors since the start of inflation targeting in the early 1990s to gauge this uncertainty, we calculate that the 95% confidence interval around the RBA’s current forecast of 2.6% underlying inflation in a year’s time is very large at 0.7% to 4.5%.

The story is the same for the unemployment rate, where we calculate that the 95% confidence interval around the RBA’s current forecast of 4.3% unemployment in a year’s time is 2.5% to 6.1%.

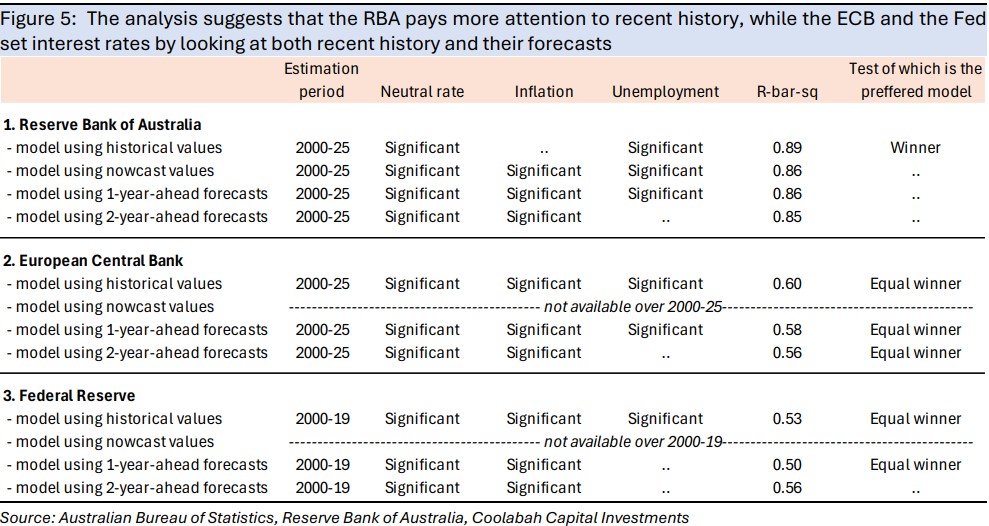

Turning to how the RBA uses its forecasts when setting interest rates relative to the ECB and the Fed, we estimated four versions of a simple interest rate rule, where the policy rate was determined by the real neutral rate, inflation, and unemployment rate relative to the NAIRU.

The four versions of the rule reflected different inputs. The first version used the latest available inflation and unemployment rates, while the second version used central bank nowcasts of inflation and unemployment. The third version relied on central bank 1-year-ahead forecasts of inflation and unemployment, while the fourth version used central bank 2-year-ahead forecasts of inflation and unemployment. The real neutral rates and NAIRUs that were common to the four versions of the rule were either central bank or economist estimates.

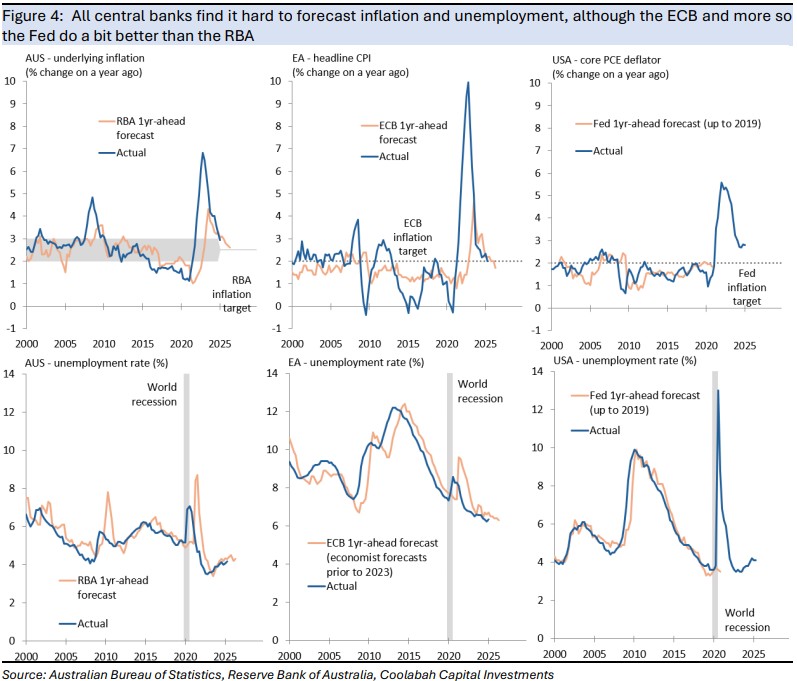

The analysis showed that all central banks find it hard to forecast inflation and unemployment, although the ECB and, more so, the Fed generally do a bit better than the RBA. The RBA might argue that it is harder to forecast inflation and unemployment in a small commodity-driven economy like Australia, but the larger economies have been buffeted by significant shocks over the years.

Nowcast errors are naturally smaller, but the ECB and particularly the Fed generally do a bit better, albeit where the latter were assessed over a smaller time span. Moreover, we found that nowcast mistakes influence the RBA’s longer term forecast misses. For example, about one-quarter of 1-year-ahead forecast error for underlying inflation can be attributed to mistakes in forecasting the current quarter, with about one-third of the 1-year-ahead forecast error for unemployment explained by nowcast misses.

Estimating the four versions of the simple interest rate rule suggested that when setting interest rates:

- The RBA looks at forecast inflation, while the ECB and Fed look at both recent and forecast inflation.

- The RBA and ECB are both sensitive to recent and forecast unemployment, with the Fed more sensitive to recent unemployment. No central bank pays attention to its long-term forecasts of unemployment.

- Neutral policy rates matter to all three central banks, even though policy-makers often publicly downplay their importance.

The analysis also suggested that the RBA pays more attention to recent inflation and unemployment than its forecasts, based on testing which version of the interest rate rule was most accurate. In contrast, the ECB and the Fed were forward-looking, with the test results suggesting they set interest rates by looking at both recent history and their forecasts.

The differences in approach could reflect the preferences of past policy-makers over the period of the analysis, where the Governor Macfarlane and, less so, Governor Stevens seemed very sceptical of the usefulness of forecasts.

This scepticism could also have been related to the unusual make-up of the RBA Board and its odd inclusion of business people, where the board of 2024 was almost the same as the one outlined in legislation a century earlier (i.e., the 1924 Act establishing the board of the RBA’s predecessor stated it should be managed by a board “consisting of the Governor, the Secretary to the Treasury, and six other persons, ‘who are or have been actively engaged in agriculture, commerce, finance, or industry’”).

However, recent extensive reforms stemming from the review of the RBA, where the RBA is adopting many of the standards of its peers, raises the prospect that it will become more forward-looking when setting policy. For example, the new Monetary Policy Board has a slightly different structure and has a sole focus on setting interest rates, where there already seems more engagement with staff in considering forecasts scenarios when deciding on policy.

5 topics