The difference between bonds and shares in a severe correction

Elizabeth Moran Consulting

The endless days of a fantastic summer are disappearing as is the consistent, upward trend of higher share prices, with volatility returning to the market. The sharp but relatively small correction in equities early February was enough to make investors stop and reassess portfolio allocation strategies. There comes a point when growth assets and the large swings in asset prices gives pause for thought.

After a ten year equity bull market, we are likely coming to the end of the cycle with the US share market near all time highs. We also know that any ripple in US equities impacts other global share markets and the Australian share market is not immune.

Further recent volatility due to fears surrounding Trump protectionism got me thinking, do investors understand the downside risk of their portfolios? What sort of losses could you expect in shares and bonds and how comfortable are you with the possibility?

What happened to CBA shares, hybrids and senior bonds during the GFC?

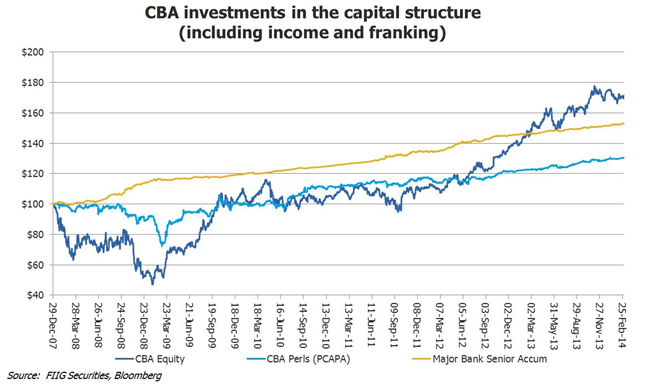

We produced this snapshot a few years ago to help identify the potential downside of another GFC type event. It shows what happened to three CBA securities – CBA senior unsecured bonds, the CBA hybrid Perls III and CBA shares over a seven year timeframe.

We assumed that $100 was invested on 29 December 2007 in all three securities with income, dividends and franking added back to show overall returns over time.

The yellow line shows senior unsecured bank bonds. It is gently upward sloping and fairly smooth, exactly what you would expect with those bonds in a crisis. They work to smooth overall portfolio returns in a correction and offset losses in higher risk assets such as hybrids and shares.

Note: The yellow line is an accumulation of the ‘big 4’ banks’ securities, as no one security spanned the full period. Also, as bonds near maturity the bond price moves towards $100 face value. So, the line is composed of all four major bank senior debt returns – it’s helpful that there is very little difference in how the bonds trade between the four banks.

The pale blue line shows the hybrid, which is more volatile. If you were a forced seller in March 2009, you would have lost around 30% of the value of your capital. It doesn’t ever overtake the senior bond as it was an older style perpetual hybrid, that didn’t have a maturity date and the bank was never obliged to repay investors.

Finally, the dark blue line shows CBA shares. It has the greatest volatility and forced sellers would have lost circa 55% of their capital if they had to sell in February 2009. From that point the share price recovers, but remains quite volatile and doesn’t overtake the senior bond until approximately five years later. That is a long time.

Main takeaways:

1. Diversify - own a range of risk assets. If you held CBA senior unsecured bonds during the GFC, you could have sold these if you needed funds and waited for the shares and hybrids to recover. In hindsight, the bond investors could have sold and reinvested in the CBA shares at opportunistic levels.

2. The CBA shares were the most volatile of the three investments and were not for the feint hearted.

3. Forced sellers of the shares at the low point, would have potentially lost 55% of the capital value.

4. CBA is one of the lowest risk companies on the ASX. Yet at the low point it lost more than half its value – ouch!

What happened to the ASX 200 top ten share prices over the same period?

A few weeks ago, Marcus Padley explained his Collin Class Submarine strategy, in a Livewire note. The strategy recommends investors sell half of all stocks held if the S&P500 dropped by more than 3% in a day. This has to be one of the most honest and easy to follow strategies that I’ve come across. It takes the emotion out of the trade and its simplicity makes it easy to apply while protecting capital.

But it might not suit you to follow this strategy, especially if you are sitting on significant capital gains. It is pretty radical.

Another way to think about it is to assess the drop in capital value you are prepared to accept before you place a sell or ‘stop loss’ order. Is it 10%, 20% or perhaps 40 or 50%?

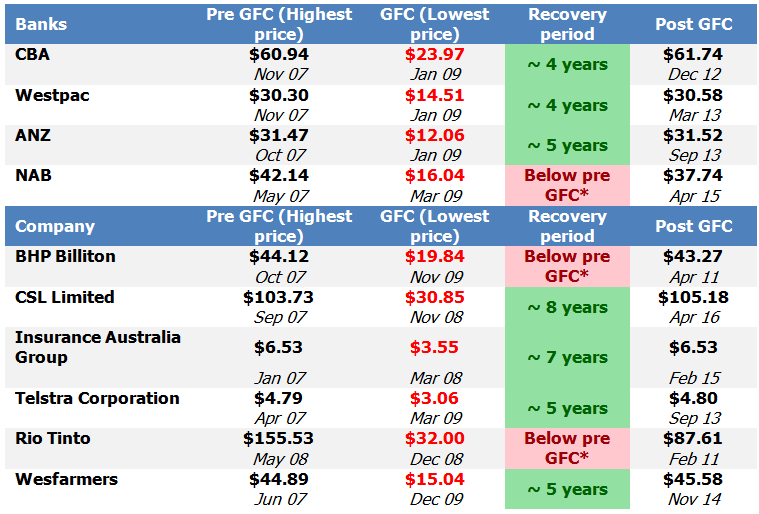

We’ve gone back to look at pre-GFC share price highs and then lows, while looking at when the share price recovered post GFC.

Of course it’s a very simple assessment. Large companies over the intervening years will have acted to boost share prices, such as instigating share buy backs, while also reducing value by a range of corporate actions such as cutting dividends, selling or spinning off assets etc.

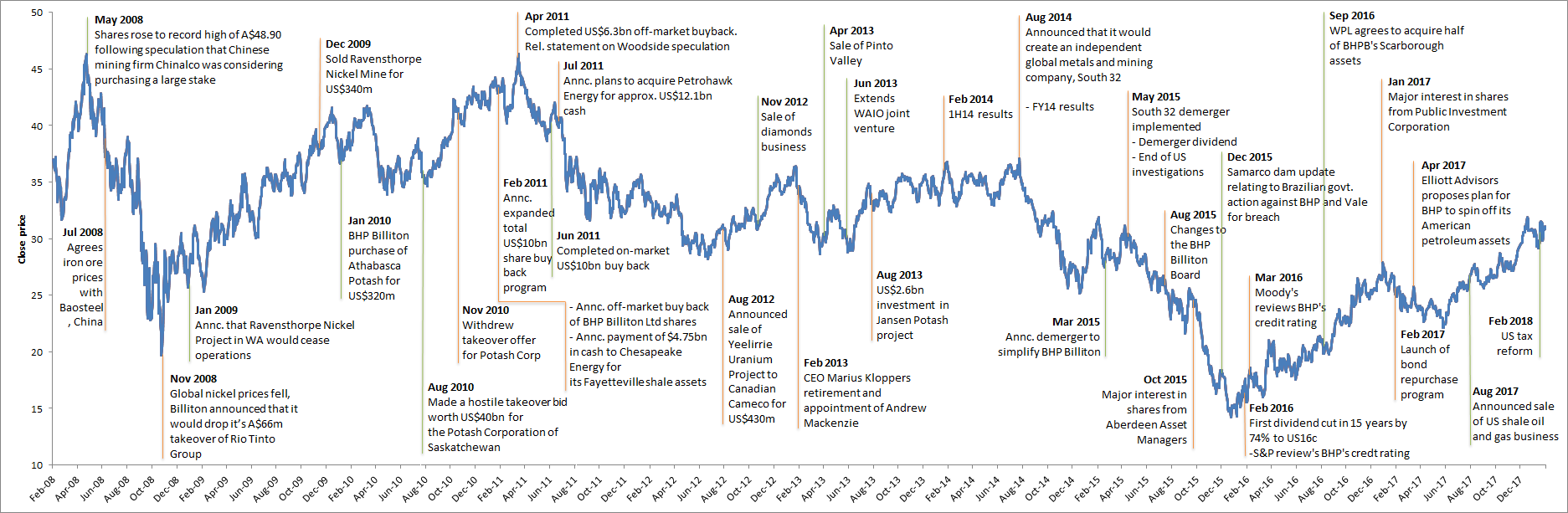

Some of the companies seem to have permanently destroyed value, not regaining pre GFC share prices. If we take BHP as an example – see the timeline below, there have been a number of influences regarding its share price.

BHP corporate actions and share price [February 2008 to February 2018]

Source: FIIG Securities, Bloomberg, company reports

Note: We acknowledge that the BHP share price is influenced by iron ore prices. Historical iron ore prices from Bloomberg aren’t available pre December 2011. For the period December 2011 to present, highest price was at USD158.00, lowest price at USD37.50 and the average price at USD89.09.

One other important point - capital losses on the value of the shares was significant, but many of the companies also cut dividends, impacting income. All four banks cut dividends, some by as much as 25%.

Corporate bond performance

Corporate bond performance over the GFC varied. Those bonds with high credit ratings, such as major Australian bank senior unsecured bonds, deemed very low risk, were sought after as they were deemed ‘safe haven investments’ and bond prices held or even rose. Those with lower credit ratings, longer terms to maturity or were lower down in the capital structure suffered. I remember an Australian dollar denominated General Electric Capital Corp (GECC) bond trading around $50 with an underlying face value of $100.

The GECC bond recovered strongly and represented good value at half its maturity redemption value of $50. In time the division was awarded bank status by the US government and protected by government guarantee. For a period it traded above its face value, providing very high returns for investors that bought at the low point.

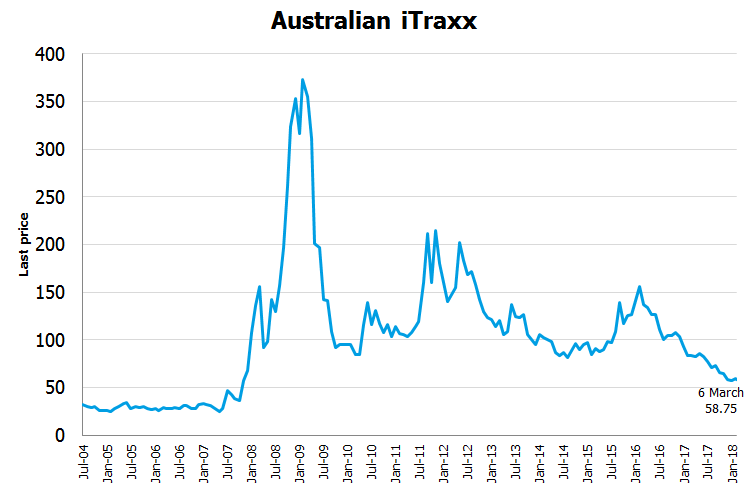

Another way to assess performance is to look at the Australian iTraxx and the blow out in credit spreads – wider spreads mean lower bond prices.

The iTraxx is an index of the 25 most liquid investment grade Australian bonds with each major bank limited to 4% of the Index. During the GFC, spreads blew out and were approaching 400 basis points (4%) over the benchmark BBSW rate. We know senior bank bond prices held but other investment grade bonds, likely lower rated, moved substantially.

However, the greatest spike didn’t last long, less than a year. While some investors undoubtedly sold, those that held didn’t have to wait long for prices to recover.

The beauty of investing in corporate bonds is that as long as the company survives, you get the $100 face value of the bond returned to you at maturity. No matter what happens to the price of bonds – even in a GFC type event – if the company survives you get repaid.

Source: Bloomberg

Unlike dividends on shares, interest income on bonds cannot be cut, so as long as the company survives income is paid to investors.

If you are preparing your bond portfolio for a severe correction, you would shorten the weighted average term to maturity of your bond holdings and also its duration – see explanations below. That way, you don’t have to wait as long to receive capital at maturity and any changes to bond prices, through say higher interest rates are minimised by reducing the term.

Investors need corporate bonds

A long period of low interest rates will mean many companies have planned for up coming debt maturities and so have reduced the risk of default on the bonds issued.

I’m less concerned about company defaults than spreads blowing out if we get a severe correction in the near term.

That does not mean you have to sell any or all of your bonds. It is just a case of recognising the likely illiquidity of higher risk bonds, and the greater impact of changing interest rates on longer dated bonds.

A severe correction will have a much greater impact on share prices and recovery times than bonds.

Through our market leading research and education initiatives, we empower investors with the latest Fixed Income knowledge and insights on Fixed Income. Find out more

10 stocks mentioned

Nationally recognised expert in fixed income asset class. Career spans more than 25 years in banking and finance in diverse positions including: education, communication, media, credit research, credit ratings and retail and commercial lending.

Expertise

Nationally recognised expert in fixed income asset class. Career spans more than 25 years in banking and finance in diverse positions including: education, communication, media, credit research, credit ratings and retail and commercial lending.