The RBA trims the neutral policy rate and lowers potential output, productivity growth, & the NAIRU

The RBA’s forecasts suggest that the RBA is assuming a short-term neutral policy rate of just over 3% and a lower NAIRU of 4¼%. The RBA has marked down potential growth from 2¼% to 2% as it revised down trend growth in labour productivity from 1% to 0.7%. The clear risk is that productivity continues to undershoot, which would place downward pressure on the estimated neutral rate – albeit countered by other influences – and suggest that the NAIRU may not have fallen by as much as thought by the RBA.

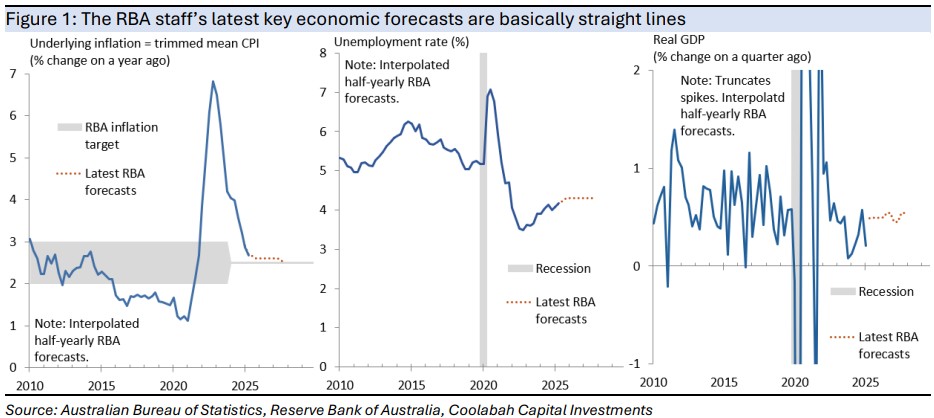

A striking feature of the RBA’s staff forecasts under the new Monetary Policy Board is how many of the latest estimates are practically straight lines.

Underlying inflation is forecast to hold at 2.6% for a couple of years before edging down to 2.5% in late 2027. The unemployment rate is expected to tick up to 4.3% and hold at that level for the entire forecast horizon, while the forecast profile for annual growth in GDP implies quarterly increases of 0.5% for almost every quarter through to the end of 2027.

The RBA has freely acknowledged that predicting the future is inherently difficult, as the Pagan-Wilcox review of forecasting at the bank made clear almost a decade ago, noting that, “forecasting is difficult and forecasts are almost always wrong, it's just a question of how wrong they'll be”.

However, it is still unusual to see such steady forecasts. Normally straight-line estimates are the product of DSGE models, which are ill-suited to forecasting and are more commonly used by central banks to help address questions about policy.

More plausibly, the stability could reflect a decision by RBA management to impose judgment by smoothing what they might regard as spurious volatility in model forecasts. Forecasters – especially market forecasters – often impose judgment based on their experience and this is a reasonable explanation for the RBA’s smooth forecasts.

Tied to the possibility of smoothing the forecasts is that the largely straight-line estimates are what the RBA regards as a “steady state” for economy, where inflation ends the forecast horizon at 2½%, the midpoint of the inflation target, and annual GDP growth matches the RBA’s newly-revised estimate of potential growth of 2%.

In turn, these estimates suggest that the RBA staff are effectively working on the assumption that the NAIRU is now 4¼%, even though their most recent model estimates suggested it was steady at about 4¾% and where the RBA board reportedly assumed that the NAIRU was 4½% earlier this year.

That is, if inflation expectations remain anchored at 2½%, then the RBA’s forecast that inflation settles at the midpoint of its target implies that there is no output gap by the end of the forecast horizon. If there is no output gap, then Okun’s law – which specifies that the gap between output and potential output is linearly related to the gap between the unemployment rate and the NAIRU – suggests that the forecast unemployment rate of 4.3% is also the assumed NAIRU.

The idea that the RBA’s current forecasts are largely “steady state” estimates is something that Deputy Governor Hauser recently encouraged when he was asked about the neutral policy rate:

- “My answer, … which I wouldn’t frame as a neutral rate, is go and look at our forecast. We’ve tried to take account of all of the available information and say, what is the outlook for inflation, unemployment, growth and so forth, conditioned on a particular [market-based] path for interest rates [and] our forecast in May … was that with interest rates following a gradual and gentle path down to about 3.2% at the end of our forecast period, inflation would come back to target. Now, it takes a little bit of intellectual agility to work out what that means but I would say not very much. I would gently and humbly encourage people to pay a bit more attention to that forecast than perhaps some people do.”

On this basis, the Monetary Policy Board would likely currently regard the forecast end-point for the cash rate – which nowadays is based on market pricing the week before the staff forecasts are published – as a short-term neutral policy rate, which the latest figures put at 3.1% (by way of comparison, RBA staff recently put the average of a range of estimates of the neutral rate at about 2¾%).

Another important feature of the RBA’s forecasts was the decision to lower its estimate of annual potential growth from 2¼%, which is also the latest median market estimate, to 2%.

The revision reflected the staff marking down assumed trend non-farm labour productivity growth from 1% to 0.7% per annum, which is based on average growth over the past twenty years. There is no obvious reason to focus on the average growth of the past twenty years, although Treasury’s dated budget assumption of 1.2% productivity growth is based on the same random approach.

Normally, lower potential growth would be expected to be broadly reflected in a similar reduction in the RBA’s estimate of the neutral rate. The NAIRU could also be higher based on Okun’s law. For example, if output was above potential such that the unemployment rate was below the NAIRU, then if estimated potential was lowered, then output would be even higher than potential and the gap between the unemployment rate and the NAIRU would be correspondingly larger.

The RBA has instead argued that both the neutral policy rate and the NAIRU are unaffected, stating that:

- “The productivity downgrade has no implications for our assessment of the NAIRU and full employment, so our assessment of labour market tightness remains unchanged. Our forecasts for activity and potential output growth have been revised down together so our assessment of the evolution of the output gap is unaffected, while our current assessment of the output gap already accounts for past low productivity growth. While in theory lower productivity growth would imply a lower neutral interest rate, in practice our model estimates … derive from the observed data, which already reflect the historical slowdown in productivity, and so are unaffected by the change in our forecast assumption.”

These are strong claims, but to be fair a ¼pp revision to assumed productivity growth is relatively small, overshadowed by the already-large confidence intervals around trend productivity, the neutral policy rate, and the NAIRU. Also, in the case of the NAIRU, it is worth remembering that Okun’s law is an observed relationship and not an identity.

The bigger issue is whether the productivity assumption remains too optimistic, posing a more material risk to the RBA’s views on the neutral policy rate and the NAIRU.

Assessing trend labour productivity is extraordinarily difficult as productivity has languished for about a decade, apart from a COVID-era spike, echoing the persistently dismal productivity of other advanced economies, bar the US.

Not surprisingly, this has seen both the RBA and the market consistently overstate productivity, continually factoring in an elusive recovery.

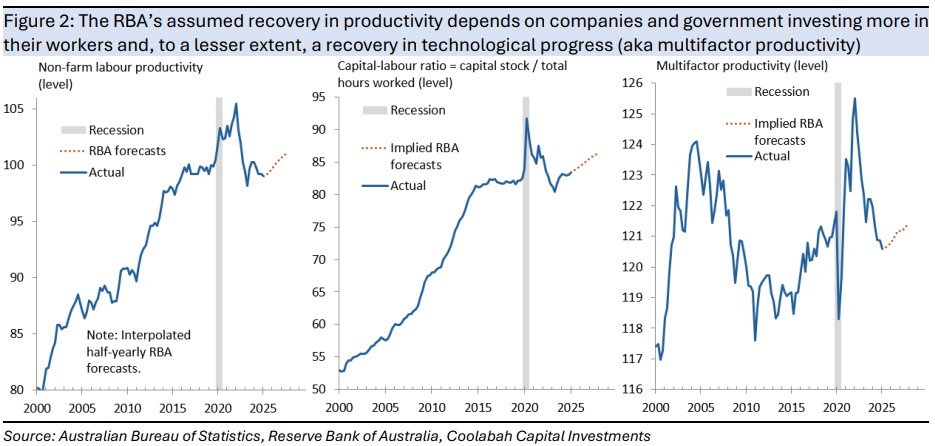

Using the RBA’s current forecasts, together with some very strong assumptions, the RBA’s forecast profile for productivity can be mechanically split into its two drivers, namely the ratio of the capital stock to labour and multifactor productivity.

Higher labour productivity could be driven by companies and government investing more to make it easier for their employees to complete work and/or technological progress making production more efficient, as proxied by multifactor productivity.

On CCI's calculation, the RBA staff’s assumption of 0.7% annual growth in labour productivity reflects forecast recoveries in both the capital-labour ratio and multifactor productivity, where the capital-labour ratio contributes about 0.5pp to labour productivity growth and multifactor productivity adds around 0.2pp.

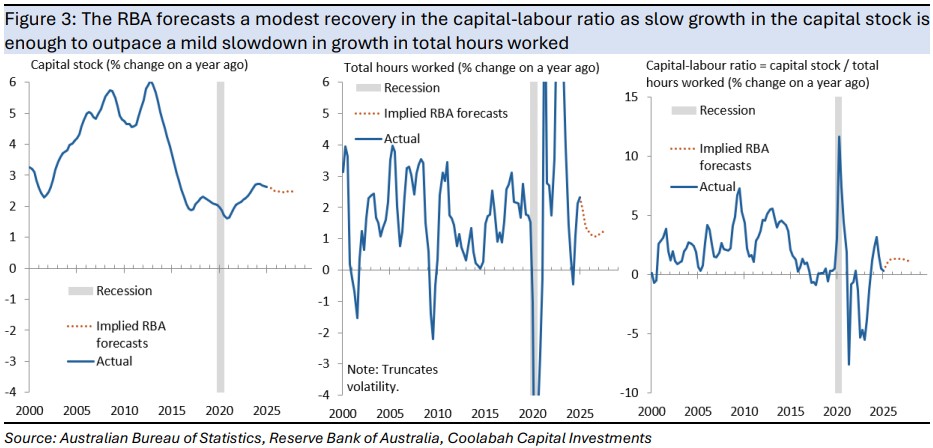

The RBA’s forecasts imply only weak growth in the capital stock, but enough to outpace an expected slowdown in total hours worked, while a recent decline in multifactor productivity is assumed to immediately reverse.

Judging how realistic this outlook is hard, but productivity could continue materially to undershoot the RBA’s forecasts, eking out small gains if companies continue to expand output by hiring more staff rather than ramping up investment.

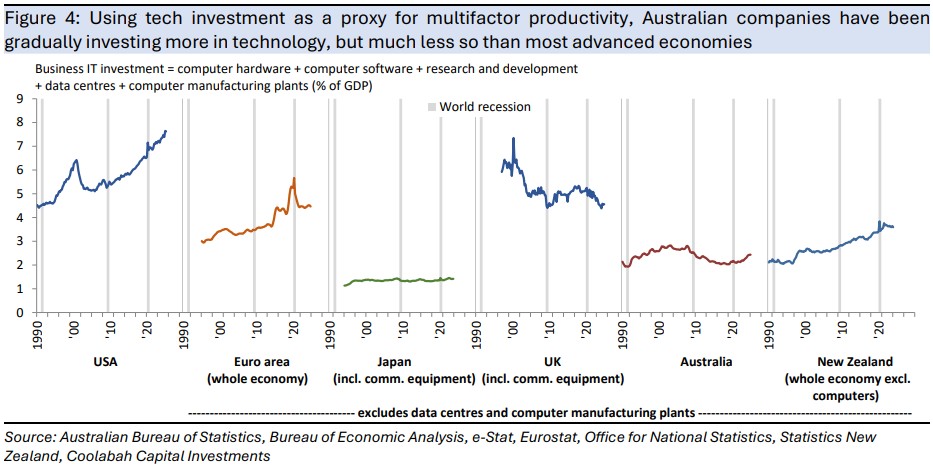

Similarly, using business investment in technology as a window into technological progress, Australian companies have recently increased their spending, but not by much and where Australia lags tech investment in most advanced economies.

If labour productivity remains weak, then this would provide a stronger argument for a lower neutral rate, albeit countered by upward global pressure on the neutral rate and the influence of largeish budget deficit, and suggest that the NAIRU may not have declined by as much as thought by the RBA.

5 topics