US tariffs, global trade & disinflation in the rest of the world

The biggest change in US trade policy in about a century has cooled world trade and upended trade flows, but there is no evidence yet that US tariffs have been mildly disinflationary for the rest of the world, where goods prices are rising again in most countries.

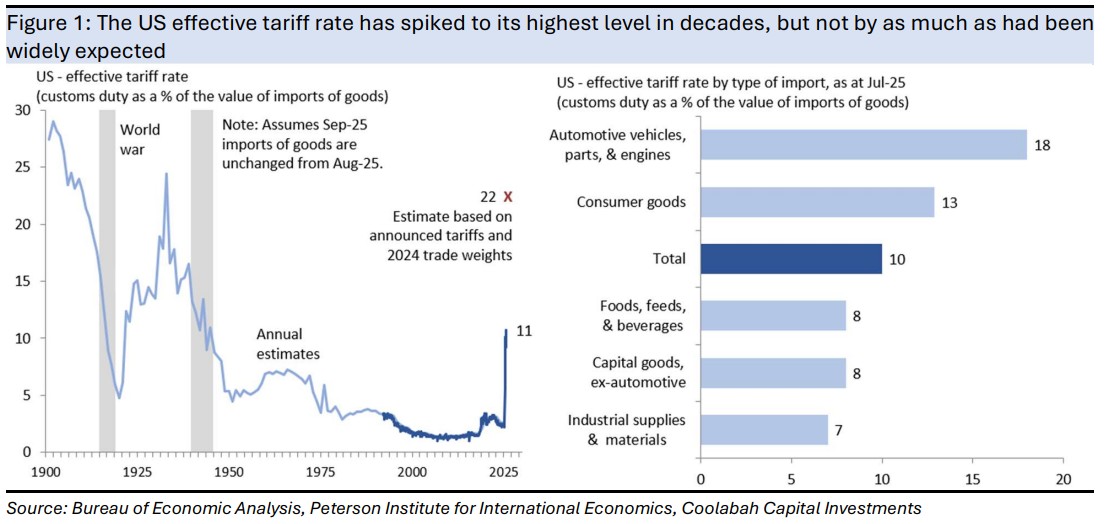

The US effective tariff rate – which is tariff revenue as a share of the value of imports – has spiked to about 10-11% over the past few months, up from 2½% at the end of last year.

This is the highest rate since WW2, but falls well short of a range of estimated tariff rates in the high teens/low twenties based on government announcements and historic trade shares.

The Supreme Court will rule on the legality of new tariffs in November, where it is not clear that the government has better-legislated tariffs in reserve, but in the meantime the government continues to announce more tariffs.

There are several possible reasons for why the effective tariff rate has fallen short of earlier estimates, including;

- A short lag between announced tariffs showing up in higher revenue, where the government is still announcing new tariffs;

- US government exemptions and deals with corporates limiting gains in revenue;

- US firms substituting away from higher-priced imports to less expensive alternatives; and

- China – which is subject to very high US tariffs – potentially rerouting sales of goods to the US through lower-tariff countries in Asia, even though the US warned it will impose punitive 40% tariffs on redirected trade.

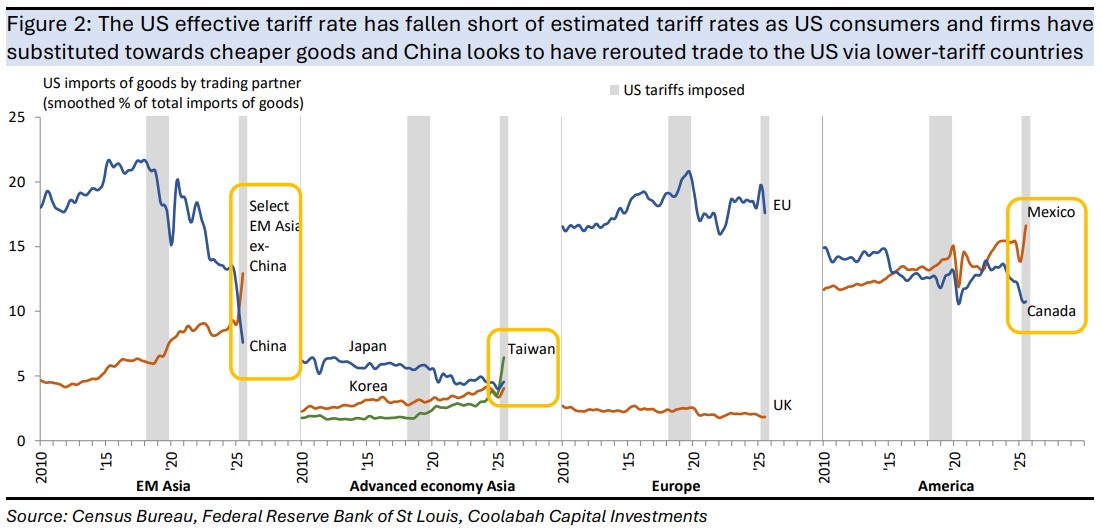

The split of US imports by trading partner shows that Americans have substituted away from higher-priced Chinese goods and bought cheaper alternatives from other countries.

China also looks to have rerouted US trade through lower-tariff countries in Asia and there also appears to be some rerouting of trade via Mexico.

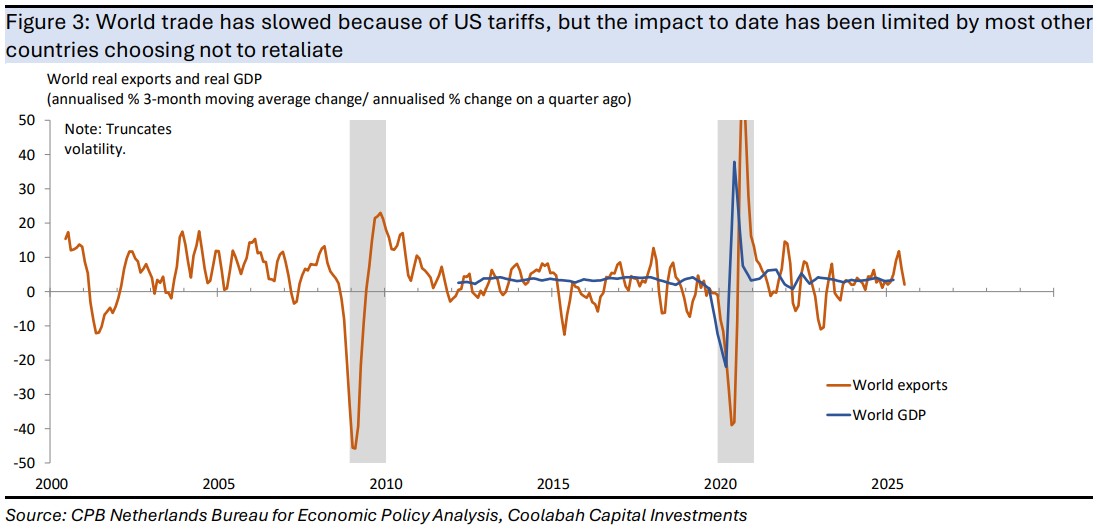

In terms of the impact of US tariffs on global trade, growth in world exports – which is a (volatile) proxy for world output – has slowed recently, but remains positive.

The saving grace for world growth has been that most other countries have chosen not to retaliate to US tariffs, with the understandable exception of China.

This is unlike the depression of the 1930s, when widespread retaliation to the disastrous Smoot-Hawley tariffs led to even weaker world output.

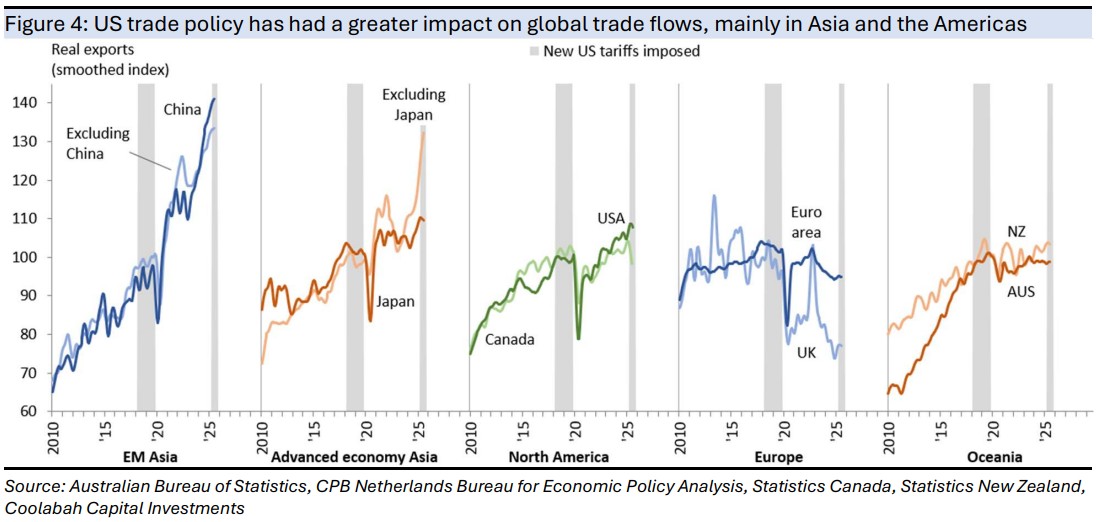

Instead, US tariffs have had a more pronounced near-term effect on world trade flows.

Chinese export volumes have started to flatten at an extremely high level, Japanese exports have slipped from a high level in real terms and other Asian exports are still booming.

Canada - America's longstanding ally - has seen its export volumes slump. European exports remain very weak in real terms, especially UK exports, which are structurally depressed.

Australian and New Zealand trends have been unaffected; Australian exports remain in the doldrums and NZ exports continue to slowly pick up.

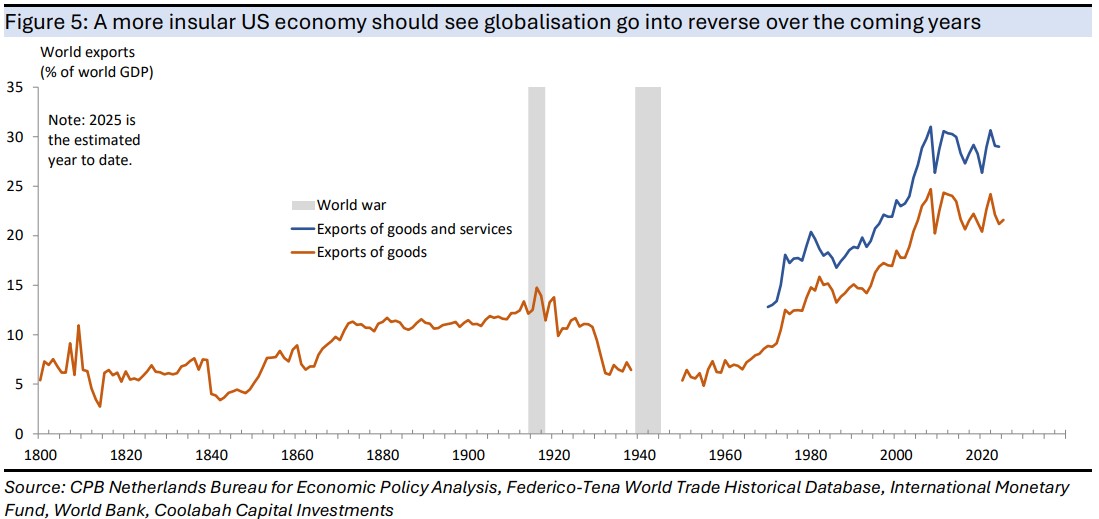

Longer term, the profound shift in US trade policy should see an unwinding of globalisation.

Globalisation – as approximated by the ratio of world exports to world output – has already broadly peaked over the past twenty years or so.

The most insular US trade policy in decades should trigger deglobalisation, leading to less efficient production, higher costs and higher prices.

The UK experience with Brexit suggests this structural deterioration should take place over several years.

The dramatic change in US trade policy has also seen many central banks, including the RBA, think that the net effect of US tariffs could be mildly disinflationary for the rest of the world,

This view rests on disinflationary forces - such as weaker world growth placing downward pressure on world prices and China selling goods meant for the US market to other countries at a discount - outweighing inflationary factors - such as disruptions to supply chains and multinational corporations raising prices globally to partly compensate for the cost of US tariffs.

Weighing these opposing forces, there does not seem to be evidence of a disinflationary impulse to the rest of the world, at least not at the aggregate level.

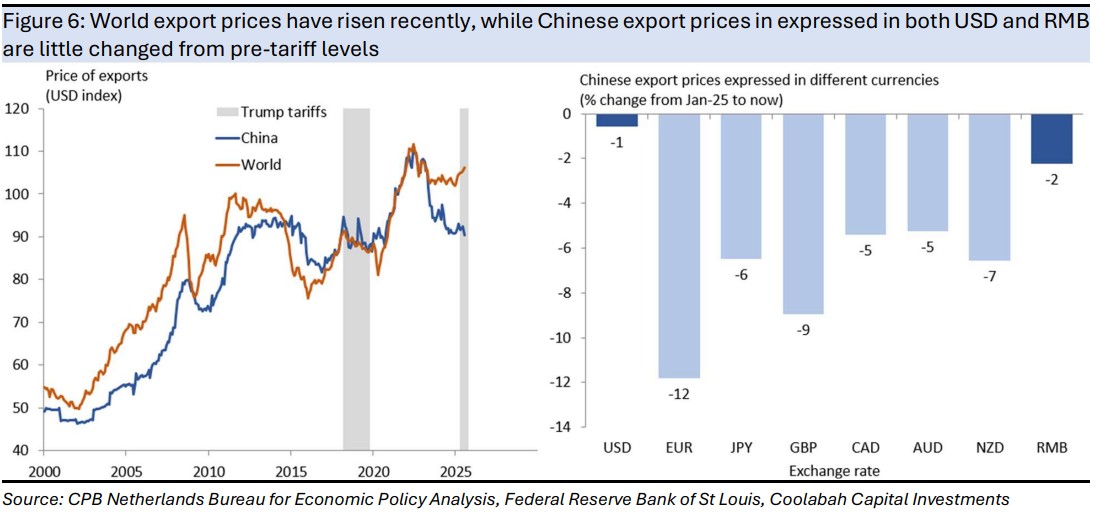

Although growth in world trade has slowed, world export prices have actually risen over recent months and Chinese export prices are little changed from pre-tariff levels in both US dollars and renminbi (the invoicing of Chinese exports is split roughly 50:50 between the USD and RMB).

That said, the US dollar has fallen in value against most currencies, making USD-denominated Chinese exports more competitive in many countries.

This means that while China’s share of the US market has slumped, its market share could continue to trend higher in other advanced economies, where it was rising in the euro area, Japan, Australia and New Zealand prior to the US tariffs.

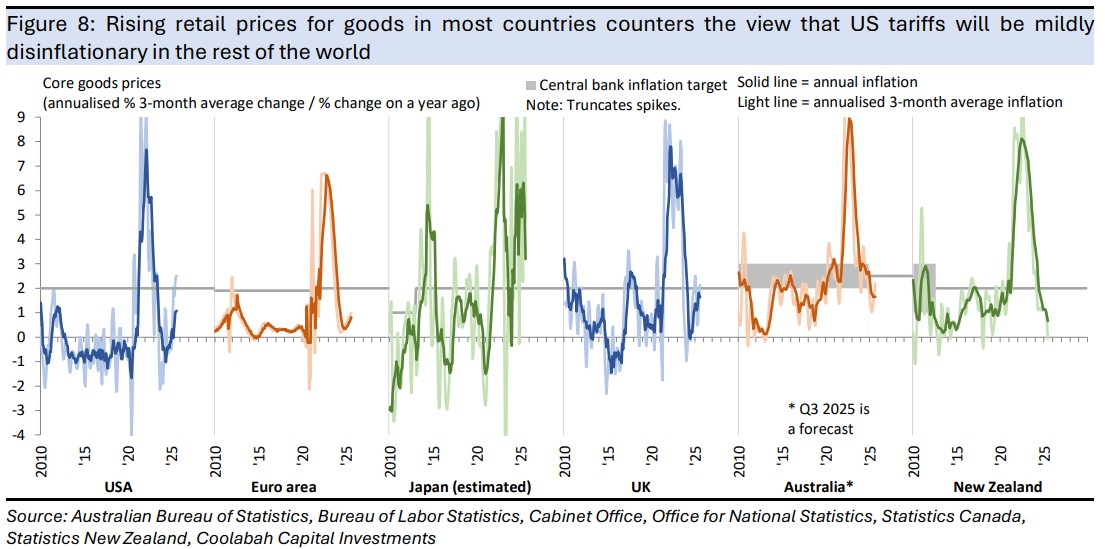

More pointedly, there is no clear sign of a disinflationary impulse from US tariffs in retail prices, where goods prices are actually rising again in many countries.

Goods prices, excluding food and energy, have picked up in the US on tariffs, but have also risen in the UK and the euro area. Prices have tentatively risen in Australia and have been growing strongly in Japan for some time. The outlier is New Zealand, where prices are weak.

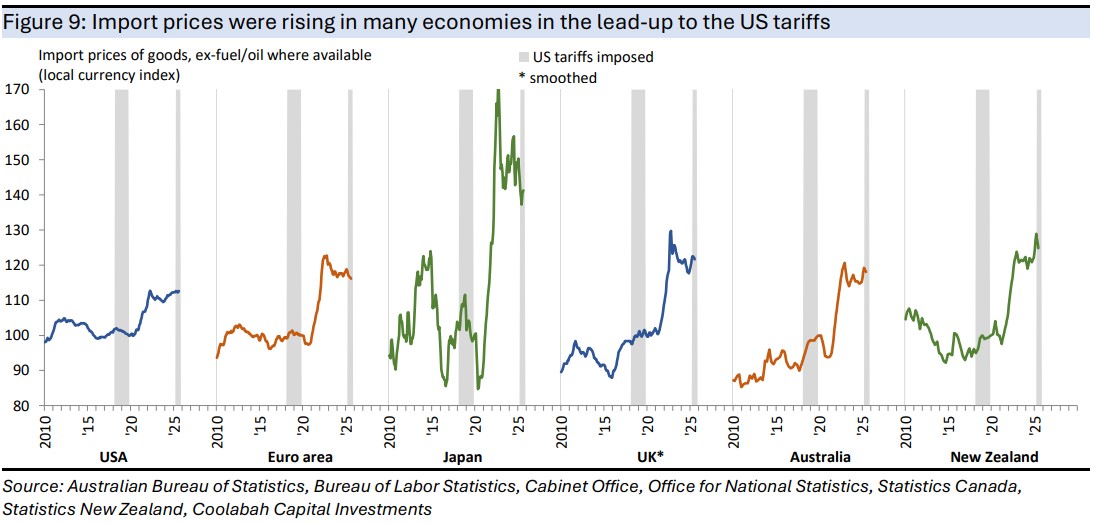

Some of the increase in goods prices reflects recent rises in import prices in several countries.

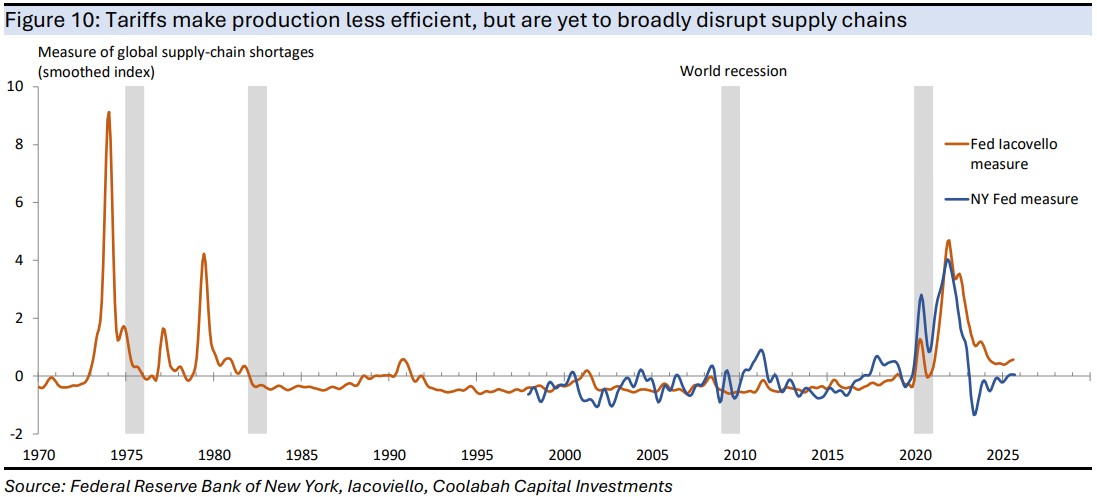

There are no broad-based supply disruptions to date, although China has successfully leveraged its near-monopoly in the control of critical rare earths in its trade negotiations with the US.

Finally and more speculatively, some multinational corporations could be evening out the cost of US tariffs by globally raising prices, even though such companies are usually thought to discriminate between different markets when setting prices.

.

5 topics