When credibility isn’t at stake

In the press conference following the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) early August meeting, Governor Bullock was peppered with questions about productivity growth. The questions logically followed from the Bank’s downgrades to productivity growth assumptions in its Statement on Monetary Policy (SoMP). However, they were also quite topical, ahead of the government’s Economic Reform Roundtable. Interestingly, Bullock had to take the unusual step of pausing the press conference to remind the audience to celebrate the “good news” of a rate cut.

In the RBA’s latest forecasts, there are no revisions to the inflation outlook, even though there is a downgrade to the growth outlook. This is because the downgrade to demand growth is completely offset by the downgrade to the Bank’s estimate of supply (potential) growth on the back of lower productivity growth assumptions. Without the downgrade to demand growth, the downgrade to supply growth would have been inflationary at the margin, and not particularly supportive of the RBA’s rate cut or easing bias. One could therefore say that the case for rate cuts is heavily dependent on its soft outlook for growth materialising.

The RBA reconciles its view that the unemployment rate will remain low with its soft growth outlook, via its productivity growth downgrade. Lower productivity growth means that more workers remain in jobs despite slower production growth. However, there is real debate about whether:

1. these forecasts are correct and

2. whether the Bank’s outlook is consistent with inflation settling within the RBA’s 2-3% target band.

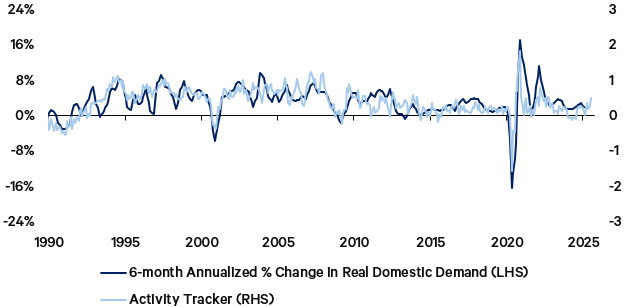

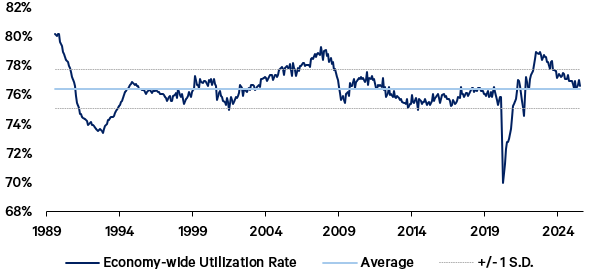

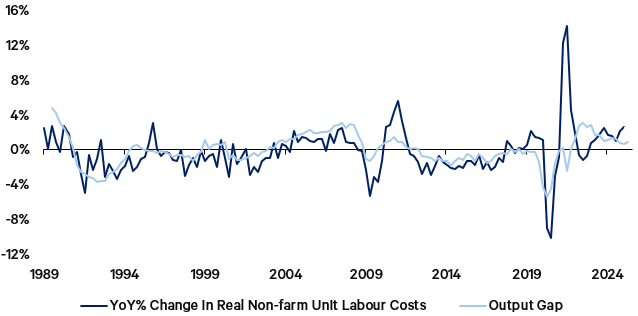

On the first question, the data do not suggest that economic growth is sluggish. To the contrary, leading indicators and company reports suggest that a re-acceleration is underway. Bullock says that the Bank’s outlook for soft growth assumes that more rate cuts will occur. However, the evidence is that the economy is already responding positively to rate cuts. Consistent with this, we see surprising tightness in resource utilisation. For example, we highlight that in the July labour market data, the unemployment rate fell to 4.2% from 4.3%. Our proprietary real-time output gap, which combines labour market data and business survey capacity utilisation, sits at 0.3% of gross domestic product (GDP), a level historically consistent with above-average wage bargaining power.

Australian domestic demand and activity tracker

Australian real-time output gap

Australian real unit labour costs and output gap

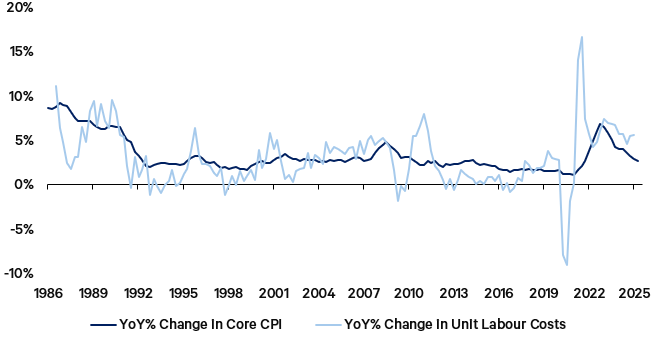

Australian core CPI and unit labour costs (wages relative to productivity)

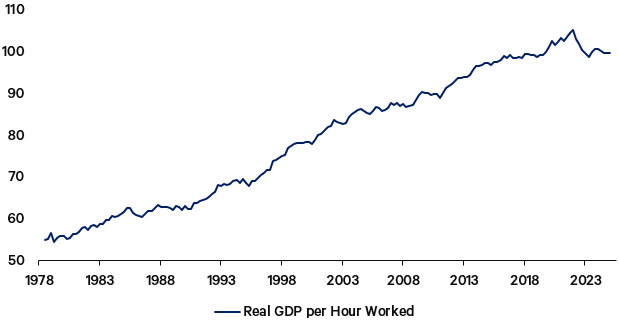

Australian productivity

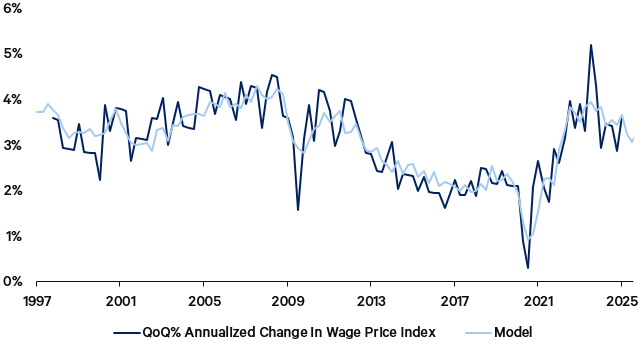

Australian wage price model index

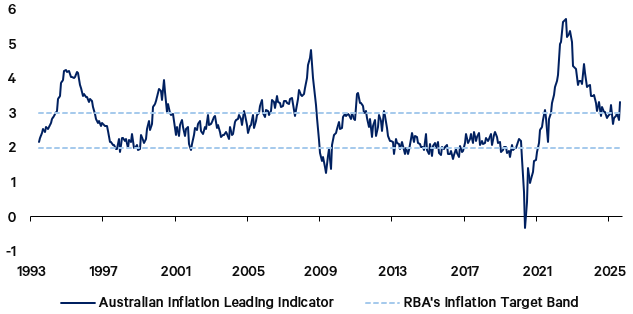

On the second question, tightness in capacity usually leads to inflationary pressures. Our proprietary Australian inflation leading indicator rose in early August to above 3%, in contrast to the RBA’s projection that inflation will slow towards 2.5%. Our model of wage inflation based on reported labour cost inflation in business surveys, labour market tightness, and enterprise bargaining arrangements, suggests that we are looking at outcomes above 3% annualised through to year end. Ordinarily, with productivity growth of 1-1.5% per annum, this would be consistent with sub-2% annualised unit labour cost inflation, and core consumer price index (CPI) inflation comfortably below the RBA’s target band. Although, if productivity continues its flat post-pandemic trend, 3% annualised wage inflation would be consistent with core CPI inflation lingering at the top end of the band.

For what it is worth, our proprietary inflation leading indicator, derived from survey evidence and bond market signals, points to inflation re-accelerating above 3% in early August. Triangulating activity growth, utilisation and inflation data, we see a consistent story of reflation, and potentially, over-stimulation of the economy.

Australian inflation leading indicator

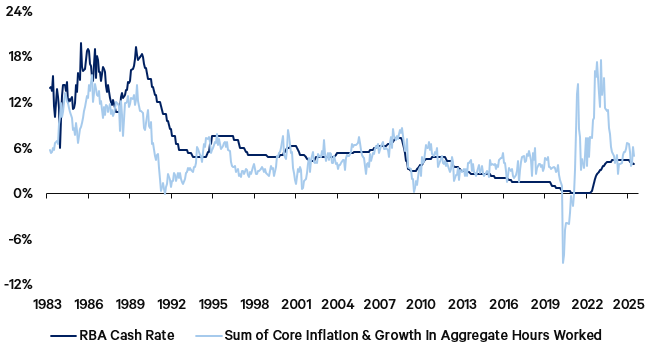

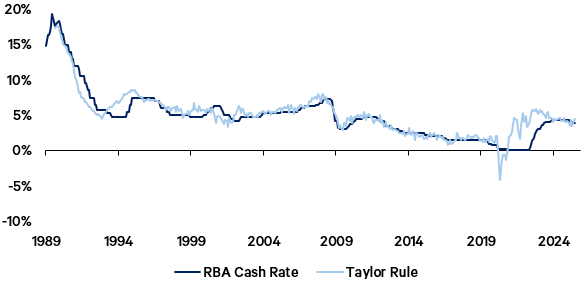

RBA cash rate and simple “Taylor rule”

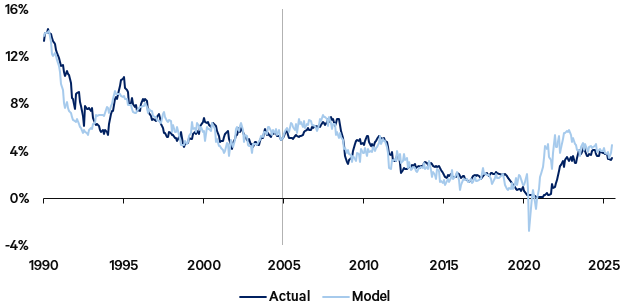

RBA cash rate and preferred “Taylor rule”

Australian three-year bond yield model

Credible policy rules suggest that the equilibrium cash rate is higher than current - not lower. For example, a simple “Taylor rule” based on the sum of trend growth in aggregate hours worked, and core CPI inflation, suggests that the equilibrium rate sits around 4.9%. A more sophisticated rule based on the sum of the output gap and the long-term neutral rate suggests that the equilibrium cash rate is 4%. Yet despite evidence of sticky inflation, capacity tightness and activity growth recovery, Bullock is endorsing the rather dovish view priced in by bond and money market investors. Indeed, Bullock is not even prepared to rule out back-to-back cuts.

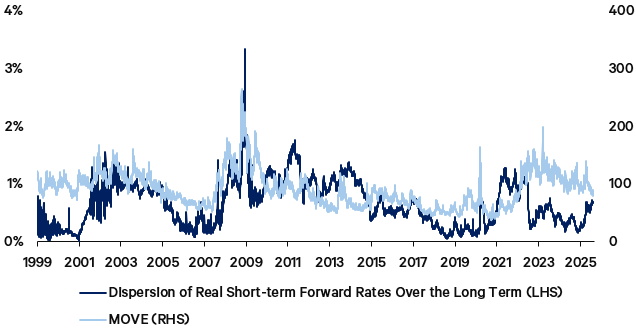

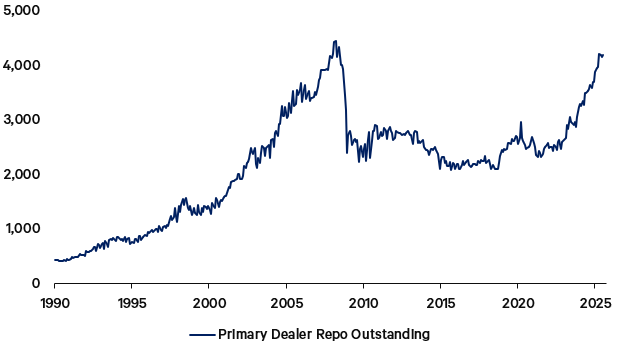

Our view is that there is upside to bond yields because too many rate cuts have been priced in, and the data suggests that these cuts are not credible - but never mind our views. The evidence domestically and abroad is that bond market investors are looking through any hawkish data points, because of global factors. For example, US Treasury Secretary Bessent is making unprecedented comments to the effect that the Fed needs to cut rates by another 1.5-1.75%, potentially starting with a 50bps cut in September. The US Treasury is skewing future issuance towards short-dated bills rather than long-term bonds and therefore stands to benefit from lower short-term rates. US Treasury issuance may be limited by higher-than-expected tariff budget revenues and managed in duration-adjusted terms by the rebalancing of debt issuance in favour of short-term bills. Weekly data on US primary dealer positioning suggests that there is an incredible amount of leverage being used to fund hedge fund bond positions, despite the inconvenience of holding physical bonds implied by negative swap spreads. In the unusual circumstances where central banks cut rates more than they should, we tend to see longer-term bond yields rise to reflect lost credibility. There is a cost to losing credibility. While we are seeing some evidence of higher long-term interest rate uncertainty … so far, the Bessent put, fiscal revenue surprises, bond issuance management and leveraged bond traders are working together to suppress short-term interest rate volatility, and cap bond yields. It is unclear whether monetary policy makers see things this way. Regardless, the point is that the cost of lost credibility from excessively dovish monetary policy is not being made known yet in bond yields, and as such, the doves are seeing a green light to cut rates, or at least, no red lights.

US real interest rate uncertainty

US primary dealer repo outstanding

Viewed in this context, a rise in bond yields would be a very surprising development that could certainly impact positioning across and within asset classes. The event to hedge against is a steepening of the yield curve (where long-term bond yields rise faster than short-term interest rates). Post-pandemic, we note that a bellwether for a surge in bond yields was central bankers running an excessively high tracking error to credible policy rules, increasing rates uncertainty. Fortunately, they are not in this position at present … but fundamentals can quickly change, especially on the inflation front. It appears that markets are waiting for evidence of re-acceleration in inflation before positioning more cautiously in bonds. In Australia, there may be an additional layer of complacency about inflation, because of the relatively muted impact of trade tensions and tariffs. Indeed, some commentators believe Australia is likely to benefit from disinflation out of China as goods are redirected away from the US to other markets, while others highlight that Australia should experience lower inflation than the major economies because of the lack of retaliation from domestic policy makers. There are merits to these views, but our problem is that inflation is still likely to be uncomfortably high, and inconsistent with the rate outlook priced into bonds.

5 topics

1 stock mentioned